Bloc of Petro Poroshenko, a pro-Western Ukrainian political party, has an interesting history that revolves around its leader and namesake, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko.

Early Political History

This history spans the gambit of Ukraine’s political field. Petro Poroshenko was a member of the pro-Russian Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (united) when he decided to create a new parliamentary faction called “Solidarity.” This faction pulled from the Social Democrats but also recruited members of the leftist Peasants’ Party of Ukraine and Hormada, a political party where Yulia Tymoshenko, one of the leaders of the Orange Revolution, got her start in Ukrainian politics.

Poroshenko later created a new party, The Party of Ukraine’s Solidarity, based on the Solidarity faction. In November 2000, this party helped create the Party of Regions, the pro-Russia party by Victor Yanukovych, the president who was ousted in the Euromaidan Revolution. For a short time, Poroshenko was a deputy with and co-chairman of the Party of Regions. However, within a year he was pursuing a connection to the Our Ukraine Bloc, led by Victor Yushchenko, the other major leader of the Orange Revolution.

These two massive shifts caused many rifts within Solidarity. Several members of the Peasants’ Party left when the party was merging into the Party of Regions. Many others left when Poroshenko tried to switch to a more pro-Western course with Yushchenko’s bloc. However, Poroshenko and many of his supporters joined the Our Ukraine bloc in time for the 2002 parliamentary elections. Although several individuals from Solidarity, including Poroshenko, won seats in that election, Poroshenko’s party separated from Our Ukraine in 2004.

Poroshenko at the 2014 Munich Security Conference. Pictured from left to right: Kiev Mayor Vitali Klitschko, President Petro Poroshenko, US Secretary of State John Kerry, and Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk. For more on Ukraine’s political leaders, see our Who’s Who of Ukrainian Politics. Picture public domain.

Poroshenko then shifted to the All-Ukrainian Party of Peace and Prosperity, a political party he had registered in 2000. However, that party never won representation, despite attempts to run with various coalitions.

Poroshenko retained relatively successful personal political ambitions however, and held several high level posts under varied governments. He served on the National Security and Defense Council for several months in 2015 under President Yushchenko. From 2007 until 2012, Poroshenko headed the Council of Ukraine’s National Bank under both the Yushchenko and then Yanukovych presidencies. He also served as Foreign Minister for a few months in late 2009 to early 2010 under Yushchenko and then as Trade Minister for almost two years in 2011-2012 under Yanukovych. He then ran as an independent for Parliament and won a single-mandate seat. He joined no faction, operating as an independent and serving on the Committee for European Integration.

All this time, Poroshenko was also actively focused on his business activities, growing his empire that had started in 1993 with investments into candy and automotive production and later came to include shipbuilding and media as well. By the time of the Euromaidan revolution, he was worth $1.6 billion dollars.

Euromaidan and After

When the Euromaidan Revolution began in late 2013, Poroshenko became an increasingly active and vocal supporter. He had worked long to try to steer the Yanukovych administration toward European integration. He also seems to have been motivated by Russia’s import ban on his Roshen chocolate brand, his flagship investment. Poroshenko gave a speech on Maidan and used his Channel 5 television station to support and give voice to the protestors. However, he was largely kept on the sidelines of the new government forming around Tymoshenko and her protégé, Arseniy Yatsenyuk.

In 2014, Petro Poroshenko brought back his old political party, Peace and Prosperity, and renamed it to the All-Ukrainian Union Solidarity. This effectively brought back his old Solidarity party, which had been dissolved in 2013 by the Ministry of Justice for political inactivity. Members of this party came from the former Solidarity movement but also drew members recruited from other parties including Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna Party.

Campaigning as independent, socially conservative party that would be tough on both Ukraine’s entrenched corruption and new conflicts in the separatist republics in the east, Petro Poroshenko himself was later elected in the first round of voting with 54.7% of the popular vote out of a field of six major candidates.

In August, after Poroshenko’s election, the party was moved to capitalize on his success and again renamed itself, this time to the Bloc of Petro Poroshenko. Former Minister of Internal Affairs Yuriy Lutsenko was elected party leader. Lutsenko had been recruited from the Self Defense Party, which had once been associated with Our Ukraine and had once been in merger talks with Batkivshchyna.

The Petro Poroshenko Bloc, was launched into first place in parliament, taking 21.83% of the popular vote and 132 of 450 seats. Many argue that Bloc of Petro Poroshenko’s success in the 2014 parliamentary elections demonstrated Ukrainians’ support for Euromaidan’s aims, and concern for Ukraine’s territorial integrity and defense capabilities. Others counter that voter participation was low or non-existent in the separatist regions of Eastern Ukraine and in Crimea, which is now claimed by both Russia and Ukraine. Thus, the results of the election supposedly do not reflect the views of all segments of Ukraine’s declared population.

The party’s platform as used for the 2014 parliamentary elections, has been translated for the first time to English by SRAS Translation Abroad Scholar Sophia Rehm and is available here.

The party’s primary objectives stated then included Ukraine’s membership in the EU, a peaceful resolution to the war in Donbas, governmental reforms aimed at decentralization and anticorruption, and increased social protection for low-income citizens.

Soon after he took office, Poroshenko advocated for a decentralization of power throughout the Ukrainian government. In newly drafted constitutional amendments, he offered, Poroshenko wanted to change the administrative divisions of Ukraine to mainly “regions, districts, and hromadas.” One of the main powers granted to local authorities under these amendments was the power to determine the status of the Russian language as long as Ukrainian remained the sole official state language. This was an attempt to diffuse one of the main separatist demands that Russian be a state language of Urkaine as well, arguing that it was widely spoken in Eastern Ukraine.

Poroshenko with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and US Vice President Joe Biden at the 51st Munich Security Council in 2015. Photo from Müller / MSC. Used under Creative Commons 3.0 Germany

Throughout this process, Poroshenko proposed to create presidential representative posts throughout the new divisions who would supervise and enforce the new amendments, and, “in case of an emergency situation or martial law regime [they would] guide and organize” within their appointed divisions.

Not much progress has been seen on the implementation of these amendments, as parliamentary opposition has been staunch. Although Poroshenko repeatedly states that he does not wish to expand the powers of the presidency, his opponents and the Verkhovna Rada point to his decentralization amendments as a thinly veiled attempt to syphon power away from the parliament into the presidency. They argue that the presidential representatives will hold the true power in the new administrative districts, and these representatives answer solely to Poroshenko, thereby giving him enormous power over the nation. Likewise, the amendments do not grant autonomy to Donbas. So, the separatists also rejected them.

Poroshenko’s peace plan to address the war in Donbas, also launched shortly after his inauguration in 2014, has also not seen much movement. The plan proposed a cease-fire with separatist forces, a “humanitarian corridor” for civilians not fighting in the war, and new presidential elections with the separatist regions participating. He also said that if his proposed peace talks were ignored, the Ukrainian government had a “Plan B” that was much more violent than the aforementioned proposal.

The peace plans have not worked, and the war rages on in Eastern Ukraine today. Poroshenko participated in creating both Minsk ceasefire agreements and in every subsequent internationally mediated peace talk, but no sustainable option was agreed upon.

In November 2018, both Luhansk and Donetsk held autonomous presidential elections that Poroshenko spoke out against and urged the citizens of the Donbas not to elect “puppet” representatives of Russia. He argued that the election was a violation of the Ukrainian government’s sovereign authority and was internationally invalid.

Ukraine Today Under Poroshenko

Poroshenko’s rhetoric when referencing the conflict and alleged Russian control had become increasingly aggressive, especially as popularity and ratings have fallen in the run-up to his re-election campaign and particularly following the Kerch Strait incident in late November 2018, when Russia fired on and detained Ukrainian ships that Russia says were trying to move through the strait without permission. Poroshenko argued that with this conflict and the renewed intensity of the war in the East, Russia is “waging an undeclared war against Ukraine.”

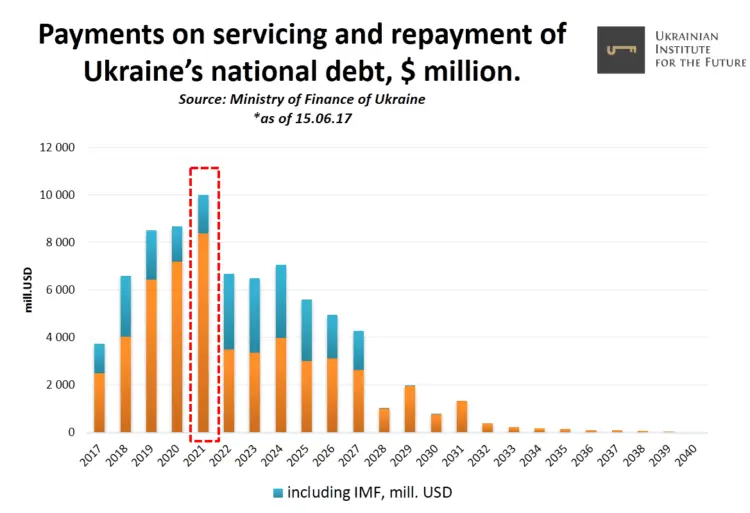

Ukraine’s debt is rising fast. Image from kennan-focusukraine.org

Corruption is another major problem that Poroshenko pledged to tackle, but has not delivered on. In June 2015, Poroshenko wrote an article for the Wall Street Journal arguing that the government had passed a number of anti-corruption laws and 2,702 former officials had been arrested on corruption charges. Further, he began claiming that oligarchies in Ukraine were a major source of corruption, therefore oligarchies needed to be finished. In March 2015, he accepted the resignation of the oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky from governor of the Dnipro region and gave a speech saying “there will be no more oligarchs in Ukraine.”

Many opposition forces and political analysts have reviewed these claims, however, and argue that Poroshenko’s government has done nothing to fight core corruption in Ukraine, that Poroshenko allows friendly oligarchs to remain in power and that, of course, Poroshenko, as a billionaire and long-standing political figure, could himself be classed as an oligarch.

One of the places Poroshenko’s incomplete reforms are most evident is in the floundering Ukrainian economy. Following the Euromaidan Revolution and the subsequent annexation of Crimea, the total GDP of Ukraine dropped 12%. This was in part due to loss of territory, but also due to disrupted logistics networks, disrupted trade with Russia, and increased uncertainty in the economy for consumers and investors.The World Bank found, however, that Ukraine’s GDP grew 2.3% in 2016, therefore ending the post-Maidan recession. This growth rate continued into 2017 and the beginning of 2018, which saw a 3.4% increase in GDP, but stagnated with delays in reform implementation due to uncertainty regarding the upcoming election.

Poroshenko (center, blue suit) in Istanbul, receiving a tomos declaring the Ukrainian Orthodox Church to be Independent. The tomos is considered to be a major achievement of his presidency and a major component to his 2019 reelection campaign. Photo from President.gov.ua. Used under Creative Commons 4.0

A more pressing problem is inflation, which increased from 12.1% to 48.68% in 2015, and has continued stay in the double-digits. The IMF proposed a four-year plan to assist the Ukrainian economy with the stipulation of implementing new economic reforms. The Ukrainian government failed to make progress on these reforms, causing a lull in assistance in 2015. Assistance began again in 2016, but the IMF declared that anti-corruption must be a primary focus for the Poroshenko Administration. While positive in nature, these loans have significantly affected the public debt of Ukraine. In conjunction with the Russian trade ban, Ukraine has refused to repay a $3bn loan from Russia taken during the Yanukovych administration. The addition of the IMF loan raised the public debt of Ukraine to an all-time high of 81% of the nation’s total GDP in 2016. The ratio has decreased since the initial implementation of IMF assistance, but the percentage remains in the low 70s.

With all of these changes in the state economy, the real wages have increased each year but fluctuate within each fiscal year. From September 2017 – September 2018 real wages increased by 12.9%, but decreased by 1.2% from August 2018 – September 2018. This growth is projected to stagnate in the coming years, however, as more Ukrainians are migrating to the EU and the United States, searching for better opportunities. Much of Poroshenko’s competition has pointed to his failure to implement certain IMF reforms and his inability to stabilize growth in the Ukrainian economy.

For the upcoming presidential election, public opinion polls show him trailing far behind many of his opponents. Most polls show Poroshenko falling behind: Active Group shows him at 14.4% approval (Tymoshenko and Zelensky at 20.8% and 20.4%, respectively) and Blue Dawn Monitoring shows him at 10.3% (Tymoshenko and Zelenksy at 22.6% and 13.6%). Ukrainian Politics Foundation is the only poll that shows Poroshenko close to the other candidates at 15.1% (Tymoshenko and Zelensky at 18.1% and 12.8%). From these polls, the consensus is that Poroshenko’s time as President has not been as successful as the Ukrainian people wanted and he will struggle to change these perceptions in time for the March 2019 election.