Krakow was the Polish capital from 1038 to 1596 or approximately from the Kingdom of Poland’s historical founding through its golden age. Even after the capital was officially moved, and even after Poland officially disappeared from the map, Krakow would remain an important center of Polish nationalism, playing a crucial role in the Polish independence movements that would have to fight for more than two hundred years to achieve their objectives.

Today, Krakow is still known as the “royal capital” and maintains a special place in Polish culture and history.

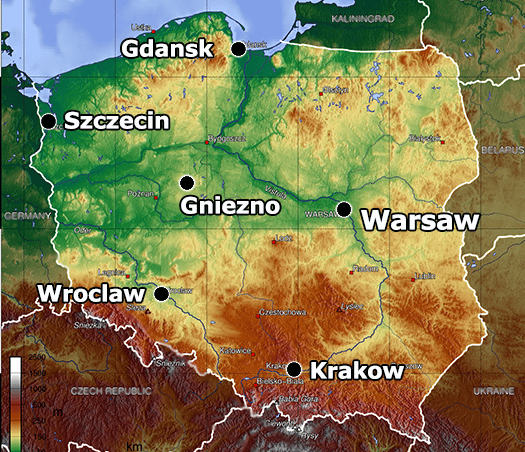

Topographic map of Poland with several major cities highlighted.

Introduction to Krakow: Geohistory

Krakow is located in southern Poland, in a valley of the Carpathian Mountains near the source of the Vistula, Poland’s major river. Already a city of importance when it was made the capital, Casimir I likely chose the location for its defensibility during a time of heightened pagan unrest and for its strategic access to mountain resources as well as to a transport route allowing him relatively easy access to the rest of his kingdom.

Today, Krakow is trying to peacefully remake its image. Through city initiatives, technology and business services firms have been encouraged to locate there. Tourism, particularly incorporating the skiing and other attractions of the mountains is being actively developed. Krakow is also playing a part in the wider Polish effort to build an inclusive, modern, European identity for Poland. Thus, for example, while Warsaw has recently opened the massive Museum of the History of Polish Jews, to honor the country’s once-great Jewish minority, Krakow now hosts the Jewish Culture Festival, Europe’s largest such festival.

All of this history and these changes are readily visible on the streets of modern Krakow.

The Royal Capital of Krakow

According to legend, a terrible dragon once lived under Wawel Hill. It was such a menace that the king offered his daughter’s hand in marriage to any knight that could slay the beast. Many heroes tried, but all were burnt to death by the dragon. One day, a shoemaker’s apprentice named Krak came up with a plan: he bought a sheep, filled it with sulfur, sewed it back up, and placed it outside the dragon’s cave. The hungry dragon swallowed it whole. The dragon’s own fire ignited the sulfur and the dragon burned. Thus, Krak won the hand of the princess, became king, and built a castle upon Wawel Hill. The name “Kraków” can be literally translated as “Krak’s City.”

In 1259, the city was again partially damaged by the Mongols. A third attack in 1287, however, was deterred due largely to newly-built fortifications. The city never came under lasting Mongol rule.

Under the enlightened Casimir III the Great (1310-1370) Krakow grew further. Krakow Academy (later renamed Jagiellonian University), was founded in 1364, making it the second oldest central European university (following the University of Prague). Wawel Castle was expanded and Kazimierz, then a Jewish-dominated suburb of Krakow, was incorporated 1335. Thanks to enforced tolerance laws, Krakow had become a magnet for European Jews – many of whom settled in Krakow’s suburbs. Several synagogues were constructed in Kazimierz, which was later incorporated into Kraków as the district of Kazimierz, which would remain the center of Krakow’s Jewish community until WWII.

An image from the Sachsenspiegel, where the basic regulations of Magdeburg Law that governed urban development (as well as – to some extent – civil and criminal law) were described in German.

Under the joint Lithuanian-Polish Jagiellonian Dynasty and the Polish Golden Age in the 15th and 16th centuries in particular, Krakow attracted many craftsmen, businesses, and guilds as the capital of Poland and a member of the Hanseatic League. Hans Dürer served as King Sigismund’s court painter and master carpenter Veit Stoss carved the world’s largest Gothic altarpiece (still on display today in Krakow’s St. Mary’s Church). Krakow was also a scientific center; the great Polish astronomer Copernicus matriculated at Jagiellonian University.

The End of a Dynasty

In 1572, King Sigismund II (the last Jagiellonian) died childless. The Polish throne passed to a succession of foreign rulers in rapid succession, causing a decline in Krakow’s importance. In 1596, Sigismund III, then King of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, King of Sweden, and the Grand Duke of Lithuania, made Warsaw his new capital, moving the Polish administrative center closer to Lithuania and Sweden in an attempt to consolidate his new union.

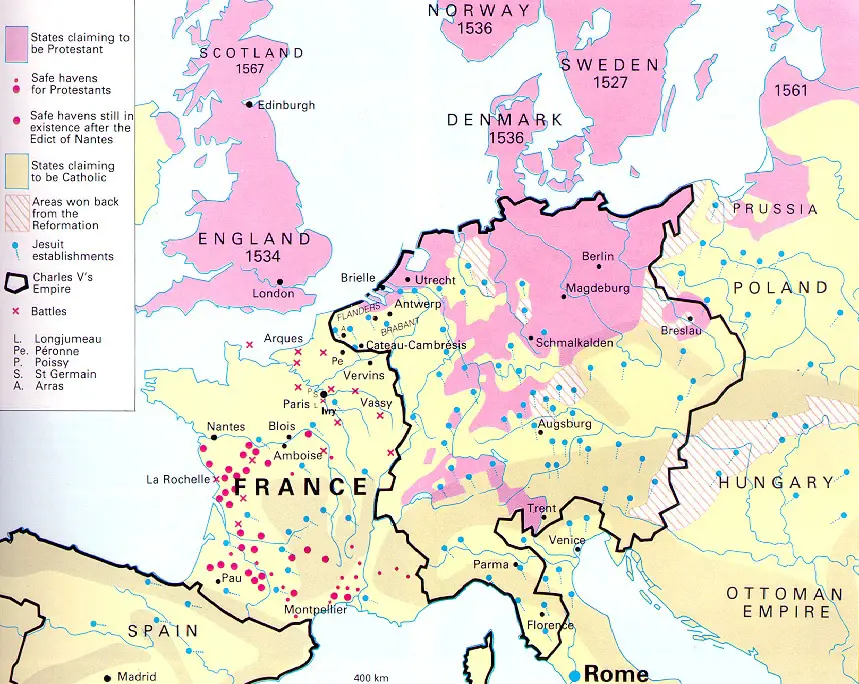

Sigismund III, a devout Catholic, was opposed by his uncle Charles, who, like most Swedes, was Protestant. Charles led a successful war to depose Sigismund from the Swedish throne and was then crowned Charles IX. Rivalries continued as both countries set sights on each other’s territory.

A map of Europe’s religions ca. 1600. As Protestantism spread, religious conflicts often resulted in full-scale war.

Eventually, the Swedish Deluge of the 17th Century devastated the Commonwealth. Swedish armies marched through the country and eventually occupied and plundered Krakow. This was followed by an outbreak of the Black Death in the city and, in 1702, another Swedish invasion that saw Wawel Castle burnt down.

Economically devastated, Poland’s political system broke down and, eventually, a civil war began. The greater powers on all sides of Poland – Austria, Russia, and Prussia – utilized the situation in the interests of their empires, and eventually carried out the first partition of Poland in 1772.

Krakow thus became part of the Austrian Empire, the most liberal of the three entities to which Polish land was partitioned. Krakow enjoyed considerably more autonomy and civil and economic freedom than other formerly Polish cities, particularly Warsaw, which regularly rebelled against Russian rule.

On March 24, 1794 Tadeusz Kościuszko, a Polish aristocrat who had fought in the American Revolutionary War and was close friends with Thomas Jefferson, declared on Krakow’s Main Square that he would lead an army to liberate Warsaw. About 6000 people joined him and were quickly defeated by the Russians, prompting the third partition of Poland, which wiped the country off the map.

A Long Struggle for Independence

The Polish nobility allied itself with Napoleon in return for the establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1809, briefly reuniting Polish lands – including Krakow – into an independent state. However, when Napoleon’s invasion of Russia failed, the Duchy was partitioned in 1815. The city of Krakow remained a separate state as a buffer between Prussia, Austria, and Russia and also as a duty-free trade zone to facilitate trade between them. Known as the “Free City of Krakow,” it had its own constitution, but was also a protectorate of the three empires. It had to seek approval for its elected president, could maintain no army, and received its police force from Austria. On the positive side, this meant that Krakow had low expenses and levied very low taxes in addition to no duties on heavy trade flowing from three major empires.

The Barbican was once connected to the city walls of Krakow and was surrounded by a moat. Krakow’s once massive city walls were first built to defend against Mongol invaders. When the walls were pulled down, a park replaced them, created a distinct ring around the city center.

The city boomed, attracting immigrants, artisans, and enterprises. It also became a center for contraband, including weapons smuggling to Polish nationalists in Russian-controlled Warsaw. Krakow itself remained a hub of nationalism and was the center of the Polish nobility-led Krakow Uprising of 1846 that sought a restoration of a united, independent Poland. After nine days, the uprising was put down and, following a secret treaty between the three empires, Austria used its prerogative to annex Krakow in the event of insurrection. The “Free City” of Krakow became the Austrian Grand Duchy of Cracow in 1846.

Despite the insurrection, Austrian rule remained quite liberal, allowing for considerable independence as well as economic and civil freedom. It became a Polish “mecca,” attracting Polish intellectuals, romantics, and patriots such as historical painter Jan Matejko and dramatist Stanislaw Wyspianski.

This helped drive economic and civic development. Like elsewhere in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, Krakow’s long-outdated medieval walls were torn down to encourage growth and commerce. Where the walls once stood, the green, ring-shaped Planty Park was established – where it continues to exist today. At the turn of the century, Krakow was a modern city with municipal water and sewage systems as well as public transportation.

With the outbreak of WWI, the Poles again pushed for independence. Jozef Pilsudski, remembered today as a giant of 20th century Polish politics, united the Polish opposition parties in the Austrian congress behind a single idea: Polish independence. He then organized the First Cadre Company out of formerly illegal pro-independence paramilitary associations in Krakow and led it to fight against Russia for its Polish holdings.

A Nazi postage stamp showing Wawel Castle as the seat of the “General Government.”

The city’s intellectuals were also liquidated and educational centers purged. Other minorities also suffered. The Nazis planned to clear the city of all nationalities except Germans – turning the city that had for centuries been a heart of Polish national identity into a fully German town.

The Nazi plan was not to come to fruition, however, and in 1945, Krakow was liberated by the advancing Red army. As during WWI, Krakow saw remarkably little damage to its infrastructure during WWII. It had, however, lost nearly all of its minorities, leaving a nearly homogenously Polish, Catholic city – which it remains to this day.

In the postwar era, the new Communist government built an entirely new, centrally-planned city on the outskirts of Krakow around the vast new Lenin Steel Mill. The city, which was named “Nowa Huta,” or “New Steel Mill,” has now been incorporated into Krakow. Vast seas of prefabricated panel apartment blocks were built to house the new workers.

Although both the Nazis and Communists tried to repress the city’s intellectual institutions, they continued operating and soon, in the 1960s, a new generation of students was pushing again for more autonomy and freedom for Poland. Krakow students went on strike in solidarity with the leftist student protests that had started in Warsaw. These protests originally asked for only reforms to the communist system, but then spread in scope and demands after being violently repressed by the security services.

Krakow is where the Student Committee for Solidarity was first founded in 1977. By 1978, similar committees had been founded in major cities across Poland. Founded specifically in response to a student activist who had died under suspicious circumstances in Krakow, these committees were also built on the same general forces that would eventually see the similarly-named Solidarity Trade Union (which would be joined by the workers of the Lenin Steel Mill) turn into the major political force that would eventually bring down Poland’s Communist regime.

Krakow’s archbishop Karol Wojtyla also played an arguably major role in the regime’s collapse. After successfully campaigning to build new Catholic churches in Communist Nowa Huta, he went on to become Pope John Paul II, the first non-Italian pope in 455 years. He held enormous influence over Poles and openly encouraged the Solidarity movement.

Modern Krakow

As one of Poland’s few major cities to not be destroyed in WWII, today Krakow is known as the “most Polish” of Poland’s cities, with cathedrals and synagogues as well as government and commercial buildings dating back hundreds of years. Krakow also boasts a strong museum culture – from the city’s own historical museum to the national museum and art gallery to the city’s several Jewish history sites such as Schindler’s factory ,the Jewish museum, and the nearby former Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz Birkenau.

The nearby town of Zakopane in the Polish Tatry (a part of the Carpathian range) is a popular day-trip destination for Krakovians. The cultural traditions of the local mountain people there (Polish: “Górale”) are popularized as Polish folk culture.

Lower costs of living of Krakow have also helped drive Krakow’s bohemian development, further encouraging students and artists to locate there. Cost of living, coupled with well-developed access to not only Warsaw but also Germany and the rest of the Central Europe has also made Krakow popular with business. The massive steel works, now owned by Mittal, an Indian multinational, is still the city’s single largest employer, although tobacco, pharmaceuticals, tourism, banking, business services, and software development are also major parts of the local economy.

Krakow’s Jewish community is now actively rebuilding as well. Although a mere 50 self-identifying Krakovian Jews were recorded in a 2002 census, today Krakow has a brand-new Jewish Community Center with more than 500 members. Many of the Jews who have relocated to Krakow have come not only for the jobs created in the diversifying economy, but also as a conscious decision to help rebuild Europe’s historically greatest Jewish community in the shadow of its historically greatest Jewish tragedy. By doing so, they show the resilience of the European Jews and honor those who died in Auschwitz.

Krakow will surely face the same challenges that Poland as a whole is facing. Low wages mean that the population is stagnant and working-age Poles often leave Poland to seek opportunities elsewhere, creating an aging society. However, Krakow, with lower average ages and higher educational levels than most of Poland, together with high investment rates and increasing diversification of its economy, is certainly in a good position to continue leading Poland’s latest rebirth and development as a modern European country.

SRAS Programs in Warsaw, Poland