Palimpsest: (n) a manuscript or piece of writing material on which later writing has been superimposed on effaced earlier writing.

Warsaw, Poland’s centrally-located capital, is in many ways an allegory of the Polish nation. The city’s ability to endure, despite repeated destruction, represents the resilience of the Poles. Unlike most modern capitals, Warsaw has spent most of the past 300 years in the hands of competing occupying powers. It has always been rebuilt, rising from the ashes again and again – albeit in varying styles often influenced by the new occupier.

Today, independent Warsaw is the economic center of Poland and alone generates about 15% of Polish GDP. Foreign investors often use Warsaw as a center of operations for their businesses in Central and Eastern Europe. The city’s new face is being constructed in modern office towers and hotels.

Although they city enjoys economic advantages, it is also, much like the rest of the country, challenged by demographic issues. These include not only those that will allow the city to continue to grow and develop financially, but also those that will permit its development into cohesive society and foster reconciliation between its conservative traditions and liberal European aspirations. All of this is readily visible on the streets of Warsaw.

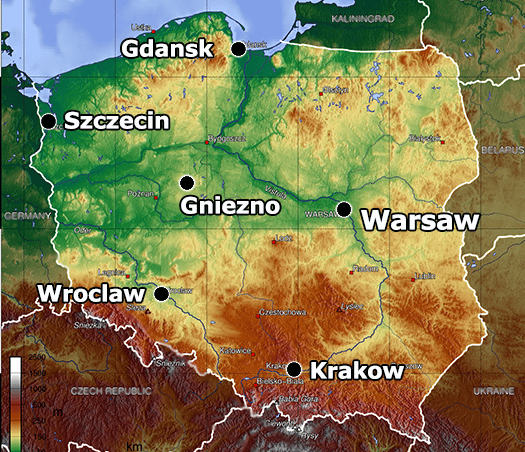

Topographic map of Poland with several major cities highlighted.

Geography and Demographics

Warsaw is the EU’s 9th largest city, with 1.7 million people, making it slightly bigger than the US city of Philadelphia.

Warsaw lies on the Vistula River, a significant transport artery running through central Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, and near where the Vistula converges with other rivers flowing into eastern Poland, giving it advantages in commerce and communication. Placed halfway between the Carpathian Mountains and the Baltic Sea, the city has a relatively humid, cool climate with temperatures ranging from around +27 F in January to about +67 F in July.

The vast sprawl of Warsaw’s contemporary suburbia is largely made up of seemingly endless expanses of uniform, prefabricated concrete apartment blocks. Gated community developments have also become very popular. Modern Warsaw struggles with transportation and infrastructure issues mainly as a result of suburban sprawl.

Currently there is no ring road around the city, which forces all traffic to congest downtown and leads to some of the worst traffic in Europe. The city’s second subway line has also been delayed for years but is slated to open in 2015.

Demographically, Warsaw, much like the rest of the country, struggles with a population squeeze from an ageing society and the loss of young skilled workers who head to Western Europe for better wages and a higher standard of living. Like the rest of Poland, most of Warsaw is dominated by ethnic Poles and practicing Catholics. Moreover, spatial segregation along racial and socioeconomic lines due to the rising popularity of gated communities is an increasingly troublesome trend.

Early History

According to one version of the legend, Warsaw was originally grounded on the site of the hut of a fisherman named Wars, who saved a lost local prince from hunger. War’s wife was named Sawa and, in honor of their good deed, the prince named the area Warsaw.

A map of Poland showing surrounding countries.

The earliest written record, however, indicates that Warsaw was likely founded ca. 1300 by Duke Boleslaw II of Masovia, one of the five duchies of Poland at the time. By 1413, the city was the capital of Masovia.

After the signing of the Union of Lublin in 1569 and the foundation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Warsaw became the permanent seat of the Sejm, a parliamentary body comprised of Polish and Lithuanian nobles. Warsaw was originally chosen for this because of its central position between Krakow, then the Polish capital, and Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. However, soon the Polish King Sigismund III Vasa moved his royal court to Warsaw in 1596, making the city the capital of both the Kingdom of Poland and the entire Commonwealth.

Warsaw grew rapidly as the Commonwealth flourished. This was cut short in the 1650s by an invasion now known as the Swedish Deluge. According to some Polish historians, the conflict left Poland with greater devastation than it experienced in the Second World War, with some 180 cities plundered and destroyed, including Warsaw. Out of a pre-war population of 20,000, only 2,000 remained in Warsaw after the war.

The Commonwealth would never really recover from the conflict. However, Warsaw, as the center of what was left of the state, was rebuilt and redeveloped. After the election of King Jan III Sobieski in 1683, Warsaw grew dramatically, both economically and culturally. He built the still-standing baroque Wilanów Palace at this time and supported Polish artists and musicians. Both the Krasiński Palace and the Sakramentek Church were originally built under his reign.

Under the Saxon rulers that followed, Warsaw received its massive baroque urban plan, called the Saxon Axis, which contributed greatly to shaping the architectural image and tone of the city, although the plan was never fully completed. The systemic demolition of “chaotic” or non-complimentary groups of buildings allowed the emergence of many important places in the capital, such as the Saxon Palace (Pałac Saski) and Saxon Gardens (Ogród Saski) which have survived until today.

A truly “golden period” of the city’s development occurred during the reign of the last Polish King, Stanisław August Poniatowski (1764-1795), which saw commerce and, perhaps most significantly, industry begin to flourish. Great monuments were created during that time, one of the most significant being Lazienki Park. Significant investments into the sciences were made and the first permanent Polish professional theater, the National Theatre (Teatr Narodowy), which still exists today, was established.

Warsaw after the Commonwealth

Warsaw remained the capital of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1796, when it was annexed by Prussia and became the capital of the province of South Prussia. It was then captured by Napoleon’s army in 1806 and made the capital of the newly created Duchy of Warsaw. Following the Congress of Vienna of 1815, Warsaw became the center of Congress Poland, which was essentially a protectorate of Imperial Russia that was gradually absorbed by the larger entity. Needless to say, the Napoleonic wars saw Warsaw damaged – not only in terms of its architecture and infrastructure, but also in terms of its population through economic disruption, forced conscription and war causalities, and reduced exports and tax collection.

Map showing the results of the three partitions of Poland.

In 1830, the November Uprising against Russian imperialism broke out in Warsaw, leading to the Polish-Russian war of 1831. Russia won that war and the city lost any degree of autonomy that it had under Congress Poland. A number of other protests against Russian rule also took place in Warsaw (particularly the January Uprising of 1863–64) but they all were put down by the Russians.

Despite the unrest, the city continued to grow overall, flourishing particularly under the tsar-appointed mayor Sokrates Starynkiewicz (1875-92), who built Warsaw’s first water and sewage systems. The Russian Empire’s census of 1897 recorded 626,000 people living in Warsaw, making it the third-largest city in the empire after St. Petersburg and Moscow.

During WWI, Warsaw was occupied by the German Empire from August 1915 until November 1918, in part thanks to Jozef Pilsudski, who led a group Poles that fought against Russia under the Austrians. Predicting the defeat of the Central Powers, Pilsudski withdrew his support in 1917 and was arrested by the Germans. The armistice with the Allies in 1919 required that Germany withdraw from areas controlled by Russia in 1914, which included Warsaw. When Germany did so, Pilsudski returned to Warsaw on and set up what became the Second Polish Republic, independent from the greatly-weakened Russia. Warsaw was the republic’s capital.

Jozef Pilsudski, who ruled the short-lived Second Polish Republic, is honored by many monuments around Warsaw.

After the Russian Revolution, the Soviets moved to take back the Polish territory lost to the Republic. In the Polish-Bolshevik War of 1920, the Poles won the decisive Battle of Warsaw, fought on the eastern outskirts of the city. With this and subsequent victories, Poland bought itself favorable negotiating terms at the treaty of Riga. Poland and Warsaw remained independent and flourished in the interwar years.

Warsaw in WWII and After

The German invasion of Poland in September of 1939 marked the start of World War II. Warsaw and all of central Poland eventually came under the jurisdiction of the General Government, a Nazi colonial administration. All higher education institutions were immediately closed and Warsaw’s entire Jewish population of several hundred thousand (about 30% of the city) was herded into the walled-off Warsaw Ghetto, the largest Jewish ghetto off WWII. Most were liquidated to nearby death and labor camps.

From August until October of 1944, the Polish resistance Home Army undertook a major operation to liberate Warsaw from Nazi rule. The operation was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union’s Red Army advance into the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces. The Soviet advance stopped deliberately short, however, in order to allow the Germans to regroup and demolish the city and defeat the Polish resistance, which was also anti-communist. After fighting for 63 days with essentially no outside support, the resistance fell.

Hitler ignored the agreed terms of his capitulation to the Soviets and ordered Warsaw to be razed and its library and museum collections taken to Germany. About 85% of the city was destroyed, including the historic Old Town and the Royal Castle.

After the war, Poland remained on the map, but Soviet troops stayed on and Stalin largely dictated Poland’s fate at the Yalta Peace Conference. Communist influence left a major mark on Warsaw’s architectural face as the city was again rebuilt. A campaign called “bricks for Warsaw” was initiated, and large prefabricated housing projects were erected to address the housing shortage as citizens and soldiers returned. Other buildings typical of Eastern Bloc architecture were also erected, such as the Palace of Culture and Science, a personal gift from Stalin and the Soviet Union.

The new Polish Communist regime initiated a “Three-Year Plan of Reconstructing the Economy.” This centralized plan, supported from Moscow, sought to rebuild Poland and Warsaw in particular. Carried out between 1947 and 1949, it was largely a success, particularly in rebuilding Polish industry and agriculture.

Unfortunately, the Three-Year Plan would be the only efficient economic plan in the entire history of the People’s Republic of Poland.

After his election as Pope, John Paul II, originally from Krakow, Poland, visited his native country in 1979 and 1983, bringing support to the budding Solidarity movement. In 1979, he celebrated Mass in Warsaw at Victory Square (in post-Communist Poland, it would be renamed Pilsudski Square, after Jozef Pilsudski). The Pope ended his sermon there with a call to “renew the face” of Poland. His words were understood by the Poles as encouraging democratic change.

Post-Soviet GDP per Capita: While “shock therapy” in Russia meant falling living standards for more than a decade, Poland’s “shock therapy” was much more successful.

With the fall of the Communist government in Poland in 1989, Warsaw underwent a rapid transition from a command to market economy. Closed since WWII, the Warsaw Stock Exchange reopened and became an important market in central Europe. Following the country’s difficult “shock therapy,” an economic and construction boom dramatically reduced unemployment and transformed the city’s skyline yet again as it benefited from local investment and also from being a center for regional investment.

Warsaw’s Modern Challenges

Warsaw has had the opportunity to rebuild itself on multiple occasions and its most recent architectural reinvention shows the imprint of at least three historical memories. First there is the medieval Old Town, completely destroyed in WWII but today meticulously restored in every detail. Second, there is the Socialist city of enormous prefabricated housing complexes, meant to bring the worker into the heart of the city. Finally there is the most recent, capitalist vision of the city, with Warsaw’s modern business skyline.

Warsaw’s largest challenge is to improve its residents’ quality of life. Living standards (pay, local purchasing power, access to high quality infrastructure and a clean environment) remain behind that of neighboring EU capitals. While low wages have helped to draw investment to the city, it has hurt the country’s demographic situation; low quality of life in developed countries usually results in low birth rates. Eventually, this could cause major economic disruption.

Monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising during WWII. Like many of Warsaw’s monuments, it conveys masculinity, perseverance, and suffering.

Interestingly, Warsaw’s suburbanization process has led to more Poles living in gated communities than anywhere else in Europe. The communities are popular with younger generations and are known in some instances to cause social issues such as segregation and stratification between classes.

Beyond economic challenges, Poland is also facing a challenge in rebuilding its national image after centuries of oppression. This is also readily visible in Warsaw.

The dominant narrative and tone of the city’s monuments and museums exalt the strength of the Polish nation and its pantheon of masculine national heroes who fought for the Polish state, often against incredible odds. The monuments and museums thus also commemorate Polish suffering, which gives a strong undertone of victimization.

Historically, both suffering and strength are undeniably part of the Polish experience. However, a challenge posed by this is that many minorities in Poland have also suffered. These include Jews, Ukrainians, Belorussians, and Germans. Further, some of these groups, particularly Germans and Jews, are, particularly by Polish nationalists, represented as a threat to Polishness. Recognizing the experience of the minorities, and encouraging social cohesion and inclusion is a challenge Warsaw’s authorities face as they try to build a free and democratic city.

Some significant strides have been made towards this. For example, the recent unveiling of Warsaw’s museum to the Polish Jews represents a major effort to encourage local recognition of positive role that Jews have played in Polish history as well as how they have been victimized. However, Warsaw and Poland also struggle, for instance, with the issue of restitution of property taken from WWII-era Jewish residents. As of yet, Poland is the only European country not to have resolved this issue and although it seems to have been making progress in the area, no deal has yet to have been made.

Challenges to integrating with Germany and accepting Poland’s German minorities were especially prominent between 2002 and 2006 under the leadership of Lech Kaczynski. As Warsaw’s mayor, the conservative Kaczynski banned gay pride parades (while supporting “normalist,” anti-gay marches). He also echoed a populist anti-German sentiment that called for reparations from Germany. Later, during his presidency, he continually emphasized the “danger” from Germans expelled from their homes when Poland absorbed considerable German territory when European borders were redrawn immediately following WWII. Kaczynski claimed Germans wanted to take back Western Poland for Germany.

Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz was elected as the first female mayor of Warsaw in 2006. Since then, the city has gradually become a more cosmopolitan and progressive capital, reflecting a general shift in Poland to more moderate policies. Gronkiewicz-Waltz’s Civic Platform Party gained control of the government in 2007.

Nonetheless, although these movements seem to represent the majority of voters at the moment, there is still considerable opposition to these liberalization efforts by Poland’s traditionally conservative, Catholic society. Two contentious sites in Warsaw that are symbols of this divide are the “diversity rainbow,” (which has been the site of protests and has been torched on more than one occasion) as well as the controversy surrounding the cross outside the presidential palace. Another controversial site surrounds the building of a “monument to the righteous Polish Gentiles” in the former Warsaw Ghetto. Meant to honor non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust, it has evoked criticism from both Jews (as a competing site of memory) and from some of the Polish intelligentsia.

Thus Warsaw, evolving from its conservative and patriarchal past, finds itself on a rocky “path of progressivism” – but not without resistance. The interactions between Warsaw’s liberal and conservative tendencies will dictate the future of the city’s identity and its international recognition.

SRAS Programs in Warsaw, Poland