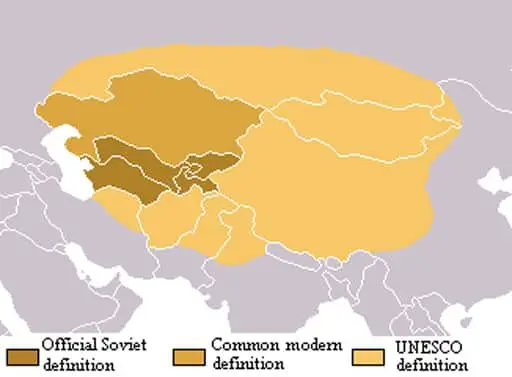

Central Asia is, by its most common definition, those five “stans” that were formerly Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. However, this has not always been the case and there are credible arguments for using other definitions.

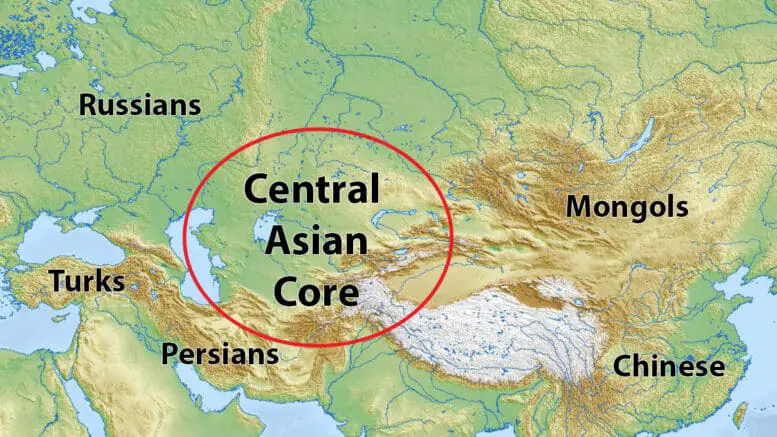

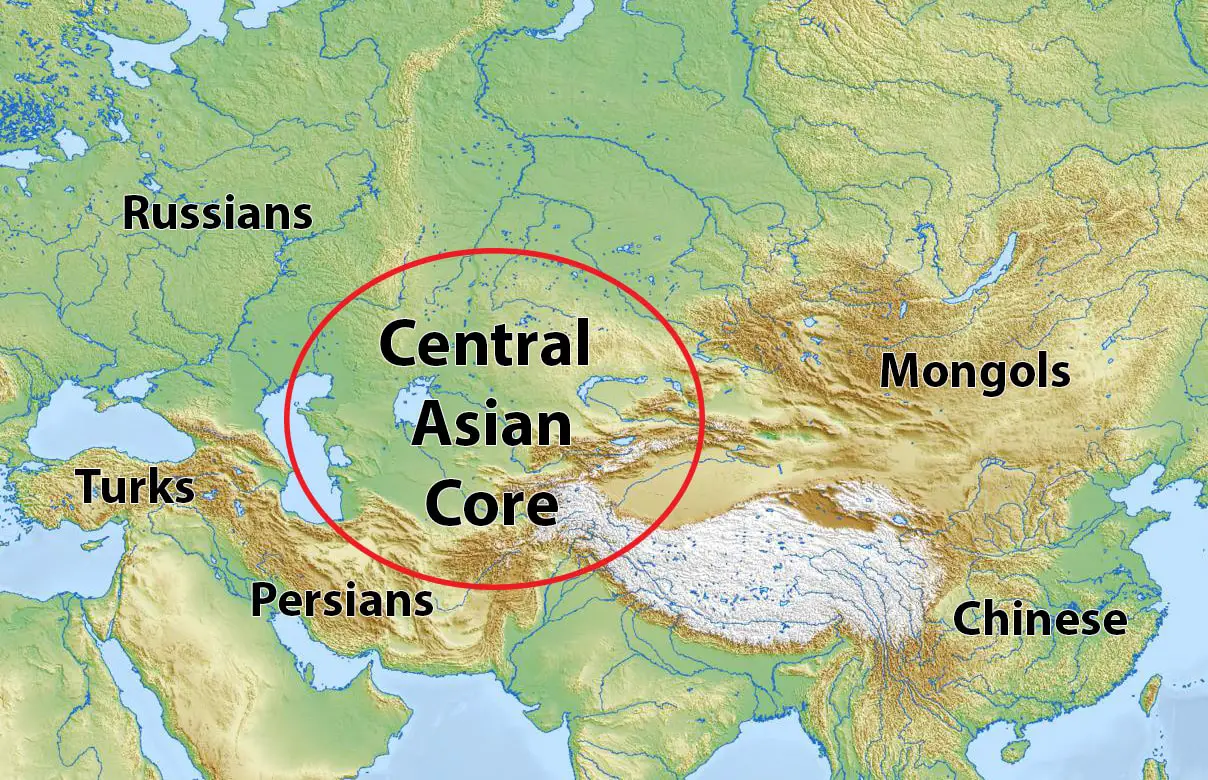

Geographically, the Central Asian region is centered on a pocket of relatively flat land bordered by mountain ranges on the east and south and by the Caspian Sea on the west. These loosely contained natural borders create a bowl in which weather patterns, plant and animal species, and human populations have all interacted and mixed for centuries. Thus, all five countries have come to share many similarities; for instance, all are majority Muslim, most speak Turkic languages, and many culinary staples (such as plov and lagman) are shared.

Political borders continue to be the most often used as they are the most practical in considering the grouping in terms of modern identity and geopolitical prerogatives. However, using modern political borders to define a region can be problematic. It overlooks the fact that the historical, cultural, and even geographical forces that created the region tend to have “borders” that flow into one another rather than starting in one place and ending in another. Thus, understanding the grouping in terms of the wider history and influences they have experienced and through the more ambitious geographical groupings that some have proposed based on these histories and influences is helpful in understanding what Central Asia is today.

Central Asia pre-1991: adding Kazakhstan

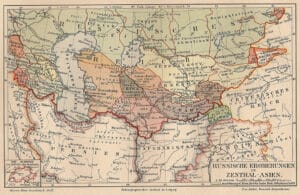

A German-language map of “Russian Conquests in Central Asia,” dated 1855. The area that is now Kazakhstan is shown as Russian and labeled generally as “Kyrgyzstan,” which was common at the time. Note as well that areas of the Caucasus are specifically shown on the map of Central Asia as well.

Ancient Turkic and Persian empires left lasting early impressions on Central Asia. Their varying borders often covered what is today Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan while Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan were more likely to be outliers – in whole or in part. Linguistic and cultural influences spread throughout the area, but these outlying countries were able to continue traditional nomadic lifestyles well into the modern era; the others converted to (more easily ruled and taxed) settled agriculture and city life.

This split continued after the term “Central Asia” gained wide English-language usage in the mid-1800s. Then, “The Great Game,” a power struggle between Russia and Britain, centered on Russia’s desire to gain access to the Indian Ocean and Britain’s desire to maintain its dominance there and control of India itself. Russia annexed Kazakhstan very early and thus the struggle focused on lands further south. The area that became modern Kazakhstan appears on maps at that time as part of Russia, not Central Asia.

Only after Kazakhstan gained independence in late 1991 did the modern grouping come into use. Based on shared culture and language, it makes sense. It can also be argued geographically as Kazakhstan is on the flat northern end of the Central Asian core, whose lands flow into Siberia. Kazakhstan is geographically connected as much to one as the other.

Grand Visions: Central Asia in the vastness of Eurasia

In the vastness of Eurasia, the challenge of placing borders on human populations and cultures becomes particularly problematic. Multiple cores have influenced and interacted with each other for millennia. Countless geographic, historical, genetic, linguistic, and cultural threads overlap over thousands of miles of territory.

As Central Asia’s post-Soviet borders were taking shape, UNESCO established a non-political definition of the region based on weather patterns. That map engulfs not only the five “stans,” but also extends well into Siberia, covers all of Mongolia, half of China, and parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

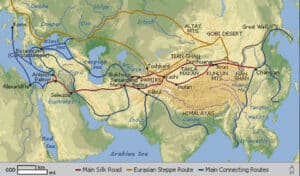

Generally, the same geographic forces (e.g. bodies of water, mountains, etc.) that govern weather also affect human migrations. Thus, much of this area shares overlapping historical threads – like Mongolian invasion routes and Silk Road transport lines. Further, much of the area is dominated by Turkic languages and Islam, including much of western China, the homeland of the Uighurs, a people that had wide influence on early Central Asian culture and whose history is tied to both China and Central Asia.

Yet, UNESCO’s map also draws in considerably more diversity, opening it to more debate. For instance, Mongolia has shared migration patterns and some cultural heritage with the more nomadic parts of Central Asia. However, it is neither Turkic-speaking nor majority-Muslim. Stretching into East Asia, Mongolia shares more cultural connections with Korea and China than does most of Central Asia. In fact, many see Mongolia as a different core altogether: one which influenced Central Asia as much as East Asia and where the influences of those regions converge.

A similarly ambitious concept is that of Inner Asia. This map draws most of Central Asia (sometimes without Turkmenistan) into a mass that stretches from Mongolia to Nepal. This can be seen on one level as mapping the far reaches of Chinese influence. Proponents of the grouping argue it is useful in mapping areas where “settled civilization” was slow to take hold. However, this again draws in populations that are not likely to see themselves as part of a single geographic or cultural unit.

Another larger concept for Central Asia is the Greater Middle East. This map, at its largest, unites a vast swath of traditionally-Muslim lands under a single label. The core of the map is centered on the Turkic and Persian empires that once ruled or greatly influenced this part of the world. It also, however, draws in diverse languages and cultures that are not likely to self-identify with a single, sweeping label. This is problematic as the Kyrgyz and Libyans, while both majority-Muslim, are otherwise quite distant from each other in geography, language, and culture.

These mega-maps are somewhat useful in exploring the far reaches of certain historical, political, or cultural influences. However, they are unwieldy in terms of trying to understand a specific area or population in any practical sense.

More Common Additions to the Central Asian Map

Most commonly used additions to Central Asia are much smaller and hold closer to the core.

Afghanistan is the most common addition. Geographically, this includes much more of the mountain range that engulfs Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and which helps form the tangible borders of the core. Historically, human migrations from Central Asia have flowed into Afghanistan since about 2000 BCE. Afghanistan was also within the borders of many Turkic and Persian empires, was a central focus for the Great Game, and was heavily influenced, though not directly ruled, by the Soviets. Thus, it has much in common with the other five “stans.”

The inclusion also makes Tajikistan less of an outlier. Tajikistan and Afghanistan are majority-Muslim, but speak forms of Persian, rather than Turkic. Given close links between Tajik and Afghan cultures and histories, there are arguments to include both if one is included. That said, those that do usually refer to the grouping as “Central Asia and Afghanistan,” acknowledging that a change has been made to the commonly-accepted definition.

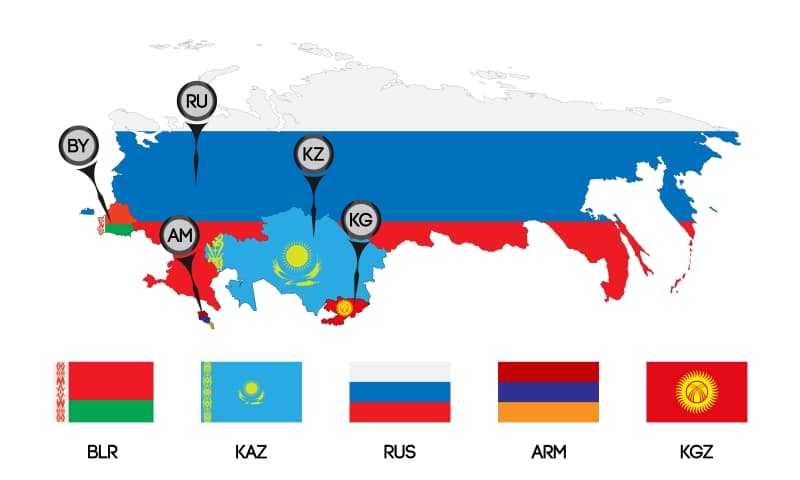

Another common addition creates “Central Asia and the Caucasus.” Across the Caspian Sea from Central Asian, the countries of Caucasus Mountains share Turkic, Persian, and Soviet influences and Silk Road heritage. Central Asia and the Caucasus both continue to be heavily influenced by Russia. Azerbaijan, specifically, is majority-Muslim, speaks Turkic, and forms a sort bridge between Turkey and the Central Asian states influenced by empires based in what is now Turkey. However, the other two Caucasus states, Armenia and Georgia, are historically Christian states. Further, their languages are neither Turkic nor Persian and their identities are decidedly separate from those of the Central Asian core. This makes directly combining the two groups difficult.

Thus, while some similar threads can be found in terms of history and modern diplomacy, Central Asia and the Caucasus are usually considered separate entities, even when they are considered as part of the same study.

The Silk Road and other major transport routes show how human migrations once brought the influences of several civilizations through Central Asia.

Conclusion: Understanding Central Asia

The partially-enclosed geography shared by Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan has led to a shared history and shared cultural elements. Further, the geographic proximity of the peoples there has allowed practical and visible cultural, economic, and political ties to develop. These encourage the residents of Central Asia to see themselves as part of an integrated unit – even when the diversity within that unit causes misunderstandings or rivalries.

The influences that helped form Central Asia are still very much in evidence. For instance, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, often outside the boundaries of empires, have typically shared a certain “brotherhood” in their traditions and similar languages. Further, the traditionally nomadic Kyrgyz have had a long-standing rivalry with the more settled Uzbeks that centered on territorial claims and water rights and extended to cultural and ethnic rivalry as well. However, both countries have made promising advancements to now place this rivalry behind them and work together to establishing transport routes, sharing water and resources, and living together in harmony.

The relatively compact geography of the Central Asian core also creates a shared geopolitical reality. The core is situated between Russia and China, two powerful and often-rivalrous countries, as well as the ambitious regional powers of Turkey, Iran, and India. These civilizations have all long influenced Central Asia. Their continued influence presents modern challenges and opportunities for investments while balancing perceived threats to their cultural, political, and territorial sovereignties.

Central Asia’s position near the center of the world’s largest land mass also creates shared developmental challenges. It is deeply landlocked and a great distance from lucrative and efficient sea routes. Thus, even those Central Asian states endowed with significant agricultural capacity or mineral wealth have been partially constrained to local or regional markets. For these countries, developing transportation routes and other infrastructure is key. Contributing to infrastructure is a key way larger powers have established influence. This is especially true of China’s massive Silk Road Initiative.

Over the past five years, Central Asia has witnessed significant developments in regional connectivity and cooperation. Many of these were achieved in 2024. A major milestone was the commencement of the long-awaited China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway project. This 523-kilometer railway, a flagship initiative under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, is designed to link Kashgar in China with Andijan in Uzbekistan via Kyrgyzstan and eventually extend to Iran, enhancing trade routes and reducing freight transport times by about a week compared to existing routes . In parallel, efforts to improve road infrastructure have also been underway, facilitating better transport links between China and Kyrgyzstan. Concurrently, long-standing territorial disagreements were resolved when Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan engaged in a controversial land swap. Similarly, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have reached agreements on 90% of their 980-kilometer border, marking significant progress in what has, at times, been violent instability. These infrastructural and diplomatic advancements underscore a broader commitment among Central Asian nations to enhance regional integration and cooperation.

Meanwhile, Uzbekistan’s new president is leading Uzbekistan away from its isolationist stance to more international investment and influence. He has also tentatively allowed some democratic reform. Alternatively, Kyrgyzstan’s new president has moved to consolidate power and ram through reforms, raising red flags for watching for “democratic backsliding” but also potentially bringing about helpful economic and diplomatic reforms. Lastly, falling energy prices have forced Turkmenistan’s strong rulers to reconsider both the populist programs and grandiose monuments that they have traditionally funded from the country’s rich natural gas deposits.

In short, the core of Central Asia has become an agreed-upon standard to define the region because it makes logical sense in terms of history, culture, and geography. It also corresponds with the lives and identities of those that live there. At the same time, one cannot fully understand Central Asia without understanding that its history, culture, and geography spills over the current political borders. To understand Central Asia, one must understand the much wider influences that have affected and continue to affect local economies, cultures, and geopolitics.

You’ll Also Love

Central Asia: Core and Periphery

Central Asia is, by its most common definition, those five “stans” that were formerly Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. However, this has…

Osh & The Fergana Valley: Diversity and Division

Boasting breathtaking mountaintop views and an expansive outdoor bazaar, Osh is one of Central Asia’s major commercial centers and one of its oldest, most socio-culturally…

Nationalism as a Political Factor in Late-Soviet Kazakhstan

“Nationalism is a political principle which maintains that similarity of culture is the basic social bond.” – E. Gellner[1] “Казахстан в современных границах исторически был территорией…

A Sovereign Surge, Not a Soviet Resurgence: The Mutualism of Eurasian Reintegration

With the creation of the Eurasian Economic Community’s customs union (“Customs Union”) in 2010, total trade among Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan skyrocketed.[1] Emboldened by such…

Turkmenistan: A Rich, Desert Land

Turkmenistan consists mostly of sparsely-inhabited desert, but has still found itself contested between civilizations throughout history. Over the past century, it has been particularly associated…