At the same time, Kyrgyzstan holds several strategic advantages. A high birth rate has produced a young, growing population with the potential to drive a thriving workforce as well as innovation, entrepreneurship, and social progress. The country’s mountainous terrain and abundant water resources support clean hydropower development, while its rich nomadic heritage strengthens national identity and fuels a growing ecotourism industry.

Kyrgyzstan has also proven skilled at balancing relations with global and regional powers including Russia, China, India, and the United States. Today, it is helping lead efforts to strengthen regional unity in Central Asia—pursuing closer economic and diplomatic cooperation to enhance development and elevate the region’s global influence. This will likely come, in large part, from efforts to better connect China, Russia, Iran, and India.

Though challenges remain, Kyrgyzstan is a small nation to watch as potential beneficiary of big changes coming to global geopolitics.

The Beautiful, Difficult Geography of Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan is slightly smaller than South Dakota at about 200 square miles. Its growing population is similar to Arizona’s at about 7.3 million. Mountains cover nearly 94% of its terrain with much of the remainder taken by Issyk Kul, a massive saltwater lake.

Elevation varies dramatically, from 4.6 miles high to nearly sea level. Thus, while Kyrgyzstan has considerable water resources, it has no navigable rivers, but instead mostly a series of rapids and waterfalls. Its longest river, the Naryn, runs east to west through the country’s approximate center. While not navigable, the land around it provides Kyrgyzstan’s longest flat transport route and was once used as a minor artery of the Silk Road. However, the river and its valley have traditionally served as a dividing line between the historically rivalrus north and south, which have had separate historical and cultural developments.

Major locations in Kyrgyzstan (including Bishkek). The large lake in the northeast is Lake Issyk Kul, a massive body of salt water and popular tourist site.

This mountainous terrain offers limited agricultural development, with less than 7% arable land suitable for intensive agriculture. Animal transport and pastoralism remain dominant in much of Kyrgyzstan, with horses and sheep commonly raised and traditional animals such as yak beginning to make a comeback.

Road and rail development are difficult and expensive, as plans for the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad show. When construction began in 2025, estimates for the Kyrgyzstan section, with its numerous tunnels and bridges to navigate the mountains, topped $4.6 billion. Combined with the fact that Kyrgyzstan is the world’s most landlocked country by distance to the ocean and the international markets beyond, the state’s economic and developmental challenges are considerable.

Kyrgyzstan possesses a range of natural resources. Its extensive glacial systems and fast-moving waters currently fuel a hydropower industry that supplies some 85% of Kyrgyz electricity production. The mountains also provide opportunities in ecotourism as well as mineral wealth including the massive Kumtor Gold Mine that regularly accounts for approximately 10-15% of GDP. Uranium and significant rare earth mineral deposits are also being explored and actively developed. However, development of resources has historically been limited by inadequate transport and political uncertainty.

Geography has played an outsized role in sculpting Kyrgyz national identity. Traditional Kyrgyz society was structured around clans that moved seasonally with their herds, living in portable yurts and relying on animal husbandry. Transport and defense relied on powerful equestrian traditions. This nomadic pastoralism, particularly well-suited to high-altitude pastures and decentralized governance, only ended with Soviet-era forced collectivization and industrialization. Cultural traditions remain strong today, finding expression in many mediums from The World Nomad Games to Kyrygz cuisine. Tribal identities also remain strong and have contributed to regional political competition, as groups vie for limited state resources and development projects in a country where infrastructure remains costly and unevenly distributed.

Relief map of Kyrgyzstan showing the country’s almost entirely mountainous territory.

Kyrgyzstan’s population is today about 73% Kyrgyz and over 90% muslim, a religious tradition that survived Soviet oppression and is now expressing itself in the mass construction of mosques. Kyrgyzstan is overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim, adhering largely to the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, which is characterized by its relatively moderate and adaptable interpretations. Religious practice varies widely, with many Kyrgyz identifying culturally with Islam while maintaining traditional pre-Islamic beliefs and customs, particularly in rural areas.

Population distribution also reflects Krygyz topography and history. The north of the country, particularly the Chuy Valley and the capital Bishkek, is more urbanized and hosts larger populations of Russians and other Slavic groups due to Soviet-era colonization. The south, especially around the Ferghana Valley, has significant Uzbek, Tajik, and Dungan communities. These demographic patterns have further contributed to regional political divisions, with the north often associated with technocratic and Russian-speaking elites, and the south more closely linked to traditionalism and Islamic identity.

Kyrgyzstan retains both Kyrgyz and Russian as official state languages. Russian remains the dominant mode of communication in Bishkek.

Having spent most of the past two centuries under foreign domination by powers seeking to use its mountains as a wall between themselves and their competitors, managing the leverage that major powers hold over it is a major concern for the small country. For instance, remittances from Kyrgyz working abroad in Russia account for 18-20% of Kyrgyz GDP and are rising in value. Also of concern is the fact that China is by far Kyrgyzstan’s largest investor and debt holder. Meanwhile, the US, which once held a military base in Kyrgyzstan and helped balance the influence of China and Russia, is increasingly disconnected. Kyrgyzstan is now part of a wider Central Asian effort to integrate the region diplomatically and economically to provide its own center of power.

Kyrgyzstan has also made advancements in domestic policy, but still needs to provide more educational and employment opportunities for its population, the majority of which is under 25 years of age. Rooting out corruption and inefficiencies so as to invest in the infrastructure to bring the country together politically and economically is also a constant concern.

Historical Background

According to legend, the Kyrgyz first came together as a nation when Manas unified the “forty tribes.” This is told in Epic of Manas, one of the world’s longest epic poems, and one that was carefully passed down from generation to generation through Manaschi, individuals who learned the poem by heart starting from childhood.

Kyrgyzstan’s five som note (worth about 5 cents) features the legendary hero Manas on one side and, on the other, Manas Ordo, a 14th century structure thought to house the remains of the hero. Kyrgyzstan recently built a large tourist park around this structure.

Kyrgyzstan’s history reads almost like an epic poem as well. Its four main chapters might be: the early civilizations, Russian occupation, the Soviet era, and post-independence. Throughout the story, dynasties, empires, and tribes have all vied for the region’s cool mountains, fertile valleys, and geo-strategic location along the Great Silk Road.

The Scythians were the first recorded residents of the region, living in the territory from the 6th century BC to the 5th century AD. Their empire stretched to the Black Sea and they were known for military prowess, horsemanship, and the ability to work fabulously detailed artifacts from gold. Afterwards came various Turkic-speaking groups, who roamed along the Altai, Xinjiang, and eastern Tien Shan mountain ranges. These nomadic groups eventually took up herding and formed the Kyrgyz ancestral tribes. Later arrivals (10-13th C.) include the Turkic Karakhanids and Yenisei Kyrgyz. While there is some historical dispute about the legacies of these various groups, historians agree that the Kyrgyz have occupied the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan for several centuries.

The Mongols took over present-day Kyrgyzstan in the 1600s. They co-opted Kyrgyz tribes, either through negotiated agreements or by force (sometimes burning whole settlements to the ground). Afterwards came the Chinese Manchus of the Qing dynasty (18th century) and then the Uzbek Khanate of Kokhand (19th century).

Under the Khan of Kokhand, the southern Kyrgyz were first exposed to Islam. In the north, the religion’s spread remained limited. There, the Kyrgyz continued to practice Tengrism well into the early 19th century. Tengrism is a shamanistic religion that worships the sky, earth, sun, water, fire, and natural objects like rocks and trees. Those who did convert to Islam often chose the Sufi sect – whose propagators allowed the converts to continue some of their shamanistic practices.

The Russians arrived in the second half of the 19th century. At the behest of the Kyrgyz, they defeated the Kokhand Khanate. The Russians then made the region a Russian protectorate. The Kyrgyz revolted against the Russians, however, when the Russians attempted to settle and “civilize” the Kyrgyz and thus threatened their nomadic and cultural traditions. However, the revolt failed and when the Russian empire dissolved and was replaced with the Soviet Union, the Kyrgyz were quickly enveloped into the new communist system and increasingly settled in collective farms, villages, and rising cities.

Under the Soviets, Kyrgyzstan’s borders were set under a greater Soviet plan to extract Central Asia’s natural resources as efficiently as possible. At first, Kyrgyz lands were part of a greater autonomous Soviet republic called Turkestan. Then, in 1924, Turkestan was divided. Later, the Kyrgyz and Kazakh, whose languages are mutually intelligible, were separated into separate republics. By 1946, the present-day borders were finalized, drawing in a considerable Uzbek minority around the Ferghana Valley to provide political opposition within the new state and prevent it from potentially uniting against Moscow. The new republic within the USSR was called “Kirgizia,” or “The Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic.”

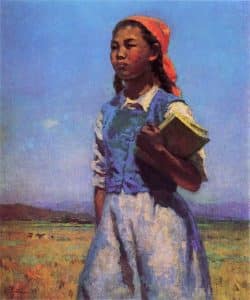

Daughter of Soviet Kirgizia by Semyon Chuikov, 1947. The Soviets forced settled life on the Kyrgyz, but also trained some of the first Kyrgyz artists in classical painting, theater, and other arts.

Life in Kyrgyzstan changed substantially. The Kyrgyz, once largely subsistence pastoral nomads were increasingly settled to work in mines, factories, and farms. Cotton and tobacco, grown with the substantial local water resources, represented a large portion of Kyrgyzstan’s exports during the Soviet era.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, Kirgizia was renamed “Kyrgyzstan,” a more Turkic version of its name. Kyrgyzstan was the first Central Asian republic to declare independence from the USSR.

Kyrgyzstan struggled in its newfound freedom. All of Central Asia was beset with tasks that were both basic and enormous. Independent economies had to be developed without once-generous Soviet subsidies and, in most cases, logistics assistance. In Kyrgyzstan, for instance, loss of access to the Soviet markets and state subsidies meant that cotton and tobacco, once important crops, became unprofitable. Further, independent government institutions and new national identities became developmental priorities, even while trying to assuage the fears of national minorities who often felt they would be marginalized in the new state. Developing effective regional relations with each other, particularly in light of the new competition for resources, the need to arrange shared resources like water sources, determining how one state could access its often numerous Soviet-created enclaves of territory within another state, and dealing with rising nationalism and the political instability that comes with an economy in chaos were just some of the Herculean tasks that now faced the newly independent states.

Kyrgyzstan, in 34 years, has had six presidents, three political revolutions, and multiple interim presidents. Kyrgyzstan’s fractured geography, pronounced regional politics, and wide range of competing political parties and ideologies have all played roles in its political instability. Further, many political groups are led by individuals who managed to concentrate wealth around themselves during the chaotic aftermath of the Soviet fall. These interests sometimes use their resources to fund armies of protestors brought into major cities from poorer rural areas. Lastly, Kyrgyzstan’s demographics are skewed toward youth, with more than half its population under the age of 25. These youth, who often feel forced to seek work abroad to care for their families in Kyrgyzstan, are often willing to fight for causes that they feel can improve Kyrgyzstan’s economy, root out corruption, and allow them to find economic success in their home country, surrounded by their families.

Kyrgyzstan’s first president, Askar Akayev, served three terms before protestors, citing corruption and abuse of power, ousted him in the 2005 Tulip Revolution. He was replaced by Kurmanbek Bakiyev, a hero of the opposition. Then he too was accused of the same crimes and ousted by mass protests in 2010 as part of the Second Revolution. For a while, Central Asia had its first female leader in interim president Roza Otumbayeva. In the elections of 2011, Otumbayeva declined candidacy to ensure that Kyrgyzstan would have Central Asia’s first peaceful transfer of power.

Almazbek Atambayev was elected and served his full term, stepping down in 2017 to comply with a constitutional one-term limit. Atambayev’s gentle reformism, respect for rules, and nomination of Sooronbay Jeenbekov, an uncharismatic technocrat, as successor were generally seen as good harbingers for Kyrgyzstan’s democratic trajectory. After his elections, a power struggle soon erupted between Jeenbekov and Atambayev, who kept his influence within his political party and prevented Jeenbekov from consolidating power. Soon mass protests over a disputed parliamentary election saw both men challenged by a party led by a wealthy businessman. Jeenbekov was forced to resign.

Current Kyrgyz president Sadyr Japarov shown with the Kyrgyz flag, which features a tunduk (the central part of a yurt) and forty rays from sun, symbolizing the original forty tribes.

Into this power vacuum, protesters supporting Sadyr Japarov, a nationalist politician with a talent for populist rhetoric, secured his release from prison where he had been serving a sentence for kidnapping a fellow public official. Japarov then negotiated his appointment to acting prime minister and then acting president. He was elected president in a 2021 landslide pledging to address public frustration with corruption, political instability, and Kyrgyzstan’s perennially struggling economy.

Since his election in 2021, Sadyr Japarov has steadily consolidated power. A new constitution has been adopted that returns Kyrgyzstan to a strong presidential system with a weaker parliament. Term limits were expanded to allow two five-year terms, meaning that Japarov can theoretically keep his seat until at least 2031. Japarov has also raised pensions, nationalized the Kumtor mine, resolved international disputes with Kyrgyzstan’s neighbors, initiated several high profile infrastructure projects, and overseen a rapid increase in the average wage. While not all of this has been universally popular, it has projected strength, created perceived stability, and resulted in high approval ratings. It has also arguably come at the cost of diminished political pluralism and growing concerns over civil liberties.

Domestic Policy Issues in Modern Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan faces a complex set of domestic challenges in 2025. The most pressing is addressing the ~30% of the population living under the poverty line and the many families reliant on remittances from relatives working abroad, primarily in Russia. Drug trafficking, mostly from Afghanistan to Russia, poses risks to security and governance.

Tensions between Kyrgyz and minority groups such as Uzbeks and Tajiks have historically been significant domestic issues as well. The most infamous ethnic confrontation between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks occurred in Osh and Jalalabad in 2010, when riots resulted in 200 people dead (most of them Uzbeks) and some 200,000 displaced. Some of this tension came from long-standing border disputes and mistrust dating back to the Kokhand Khanate. However, as of 2025, relations between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have improved significantly, with the two countries finalizing a long-awaited border agreement and making public efforts to portray each other as allies. This marks a sharp departure from the earlier years of frequent border closures and local tensions. However, challenges persist in integrating the Uzbek minority into Kyrgyz life. They remain underrepresented in political life and complain of limited access to Uzbek-language cultural and educational opportunities.

Southern Kyrgyzstan, particularly around Osh, has also been a key transit hub for drug trafficking routes from Afghanistan to Russia and Europe, posing ongoing challenges to law enforcement and regional stability. This situation is not helped by regional inequalities that still tend to favor the north over the south.

Environmental degradation has also worsened, especially in urban areas like Bishkek, where outdated Soviet-era infrastructure, poor waste management, the proliferation of automobiles, and widespread coal use to heat homes have contributed to air pollution and public health risks.

Water management remains a concern with climate change affecting the country’s glacial systems. Poorly maintained water systems threaten both agriculture and access to clean drinking water.

Kyrgyzstan’s population is growing quickly, thanks to high fertility rates that have averaged about three since independence. This is lower than under the USSR, but still phenomenally high if compared to Europe’s and the US’ below-replacement rates. Kyrgyzstan’s birthrates are often attributed to the country’s conservative values which are, in turn, driven by the heavily Islamic society. Due to this, more than half the population is under 25.

The majority of Kyrgyz live in rural areas and about 25% are employed in agriculture. Having and raising children is less expensive in rural areas and children are often considered assets on family run farms. Multigenerational housing is common in Kyrgyzstan, yet another factor that can help alleviate the burden of childcare and encourage higher birth rates. Life expectancy is also steadily rising and contributing to population increases.

Kyrgyz children gifting flowers to an elderly veteran at a Victory Day celebration in Bishkek. The hat worn by the veteran is a kalpak, the Kyrgyz national felt headwear.

This demographic profile brings both opportunities and challenges: while a young labor force has the potential to drive growth, it also places pressure on education, job creation, and housing systems. Unemployment and underemployment remain persistent, especially among youth and in rural regions. Many graduates struggle to find work in their field, highlighting a growing mismatch between education and labor market demands. For instance, universities continue to produce large numbers of graduates in law, economics, and international relations, while the economy needs more skilled workers in construction, agriculture technology, logistics, healthcare, and engineering. The IT and digital services sector shows potential for growth, but lacks sufficient domestic training programs and infrastructure to scale effectively.

The government has expanded vocational training programs and partnerships with foreign donors to bridge the skills gap, but progress has been uneven. Migration remains a common solution for many young Kyrgyz, particularly men, who often seek work in Russia’s construction, agriculture, and service sectors, leaving the domestic labor market with shortages in both low- and high-skill roles.

Wages have also risen steadily in recent years – more than doubling between 2017 and 2024, although they are still low by global standards at around $450 per month. Without robust economic diversification and investment in human capital, Kyrgyzstan’s demographic opportunity may instead become a source of social strain.

Improving economic and educational opportunities will be pivotal to bringing more of the predominantly-young 700,000 Kyrgyz who currently work abroad back home. The current migration-driven economy is not only an foreign policy and economic concern, it has also created a large population of “social orphans,” with an estimated 277,000 children living without one or both parents. Many face emotional and educational challenges, and are vulnerable to neglect despite efforts by NGOs, extended families, and the Kyrgyz government to provide support.

Kyrgyzstan’s economy also needs diversification as it is very heavily reliant on gold exports (10-15% of GDP), remittances (18-20%), and the re-export of Chinese goods (estimated at 20-40%). The nationalization of the Kumtor gold mine in 2021 was framed as a move toward economic sovereignty and remains popular, though it raised investor concerns and may still harm needed international investment in the country. Other concerns include the country’s unpredictable inflation rates (6.2% average over 10 years) and weak currency (the som has depreciated about 48% in nominal terms against the dollar over 10 years). Agriculture, textiles, tourism, and manufacturing are all considered potential growth industries that are suffering from underinvestment, low productivity, and outdated infrastructure.

Kyrgyzstan’s Foreign Relations Balancing Act

Kyrgyzstan’s most important foreign relationships are with Uzbekistan, China, Russia, and, to a lesser degree, the United States and India.

Kyrgyzstan’s relationship with Uzbekistan has historically been shaped by deep-rooted cultural and geopolitical tensions. Kyrgyzstan’s development of reservoirs and hydroelectric resources has created fears in Uzbekistan about water shortages, as Uzbekistan’s important agricultural sector is dependent on water flows from Kyrgyzstan. The treatment of Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan, especially in Osh, and even Kyrgyz memories of domination under the Kokhand Khanate, of which Uzbekistan is a successor state, has also been long standing issues.

However, in recent years the tone has shifted. In March 2025, both countries signed a long-awaited border agreement and declared a framework for “eternal friendship,” signaling a new era of cooperation with shared water and electricity resources. While disagreements still arise, bilateral ties are now marked more by pragmatic coordination than open hostility.

China is Kyrgyzstan’s largest source of imports, with Chinese goods forming the backbone of local markets and feeding a re-export economy that supplies Russia and other Central Asian countries. China is also heavily investing in Kyrgyzstan through the Belt and Road Initiative, providing financing and funding for much-needed large-scale infrastructure projects such as highways, tunnels, power stations, and railways. Investment and loans have also been extended into sectors like cement production, agriculture, and tourism. While China’s cultural influence in Kyrgyzstan remains limited and public skepticism toward Beijing persists, the economic relationship continues to deepen, with the Kyrgyz government actively welcoming Chinese investment as a pathway to development and connectivity.

Relations with Russia are characterized by deep-rooted military, economic, and cultural ties. The two countries have strengthened their strategic partnership through joint military exercises, arms deliveries, and the continued operation of the Russian air base at Kant. Kyrgyzstan has been a member of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) since 2015, facilitating trade and labor migration between the two nations.

Bishkek’s central Ala Too Square is a symbol of the country, but was built by Soviet planners – as was the majority of most of Kyrygzstan’s cities. Economic and infrastructure ties with Russia remain strong.

Kyrgyzstan’s exports to Russia skyrocketed from $393m in 2021 to more than $1.07bn in 2022. In the same time frame, Kyrgyz imports from EU countries soared by more than 950%. In 2024, bilateral trade exceeded $3.7 billion, with 98% of transactions conducted in national currencies. While this has obviously been good for the Kyrygz economy, it also likey points to Kyrgyzstan becoming a re-export country serving Russia and circumventing sanctions. Most other Central Asian and Caucasian states saw similar changes in their export and import flows. In Kyrgyzstan, as of 2025, the U.S. has only sanctioned a single Kyrgyz bank for alleged assistance in circumventing Russia sanctions.

Russia has also provided financial support through the Russian-Kyrgyz Development Fund, which approved a $150 million budget for new projects in 2025. However, the relationship faces challenges, including tensions over Kyrgyzstan’s enforcement of Western sanctions against Russia and disputes involving Russian companies operating in Kyrgyzstan. Despite these issues, the partnership continues to be a cornerstone of Kyrgyzstan’s foreign policy.

Kyrgyzstan’s relationship with the United States has shifted since the early 2000s, moving from a largely security-focused partnership to one centered on development, education, and regional cooperation. The closure of the U.S. military’s Manas Air Base in 2014 marked the end of a major chapter in strategic ties, but engagement has continued through diplomatic platforms like the C5+1 initiative and sustained support for democratic governance and civil society. The American University of Central Asia, which receives some US funding, also reflects cultural and academic ties. As of 2025, Kyrgyz re-exports to Russia have not been a major diplomatic issue.

India and Kyrgyzstan have growing cooperation in defense, trade, and education. Annual joint military exercises like “Khanjar” have become a key symbol of this partnership, focusing on counter-terrorism and mountain warfare training between India’s Special Forces and Kyrgyz units. Economically, India has extended credit lines and signed a five-year roadmap to increase trade and investment, particularly in pharmaceuticals, infrastructure, and energy. Cultural ties are also expanding through programs like the India-Central Asia Youth Exchange and support for telemedicine centers in rural Kyrgyz regions. While trade volumes remain modest, India’s growing interest in the region, driven by security concerns and connectivity ambitions, aligns with Kyrgyzstan’s desire to diversify its foreign partnerships beyond Russia and China. This balanced and cooperative relationship is likely to continue growing in current directions.

Conclusion

As Kyrgyzstan looks to the future, its ability to transform long-standing challenges into strategic opportunities will be critical. By investing in its youth, expanding its clean energy capacity, and embracing its cultural heritage as an economic asset, the country can build a more resilient and dynamic society. At the same time, continued diplomatic agility and regional cooperation will be essential for securing its place in a rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape. With the right policies and partnerships, Kyrgyzstan has the potential not only to stabilize and grow, but also to help shape the future of Central Asia.

More About Central Asia

De Jure and De Facto: An Examination of the “Friendship of the Peoples” Policy and the 1937 Koryo Saram[2] Deportation

Even though we have lived in harsh conditions we the community of Koryo Saram[3] have helped each other like brothers. We have provided each other…

Security Forces Sweep Bishkek Clean

Bishkek entered its ninth straight day of protests on April 19 with the promise by opposition leaders to dramatically increase the number of demonstrators in…

Tradition, Stigma, and Inclusion: Overcoming Obstacles to Educational Access in Tajikistan

Learning to See Invisible Children: Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Central Asia (Excerpt) Full book available in print and Kindle versions Firuza always knew that her son had…

Creating a Dam National Space: Rakhmon’s Socialist Realist Promotion of Roghun

What we have inherited is the nation state as conceptualised later on in the Soviet period. It is an ethnic nationalism centered on statehood, the…

A Comparative Look at Coronavirus Responses in Eurasia

The global health crisis has changed life around the world, but in often very different ways in various places. Even countries located close to each…