Turkmenistan consists mostly of sparsely-inhabited desert, but has still found itself contested between civilizations throughout history. Over the past century, it has been particularly associated with oppressive rule. This has remained true following its independence from the USSR. It has also remained true as exports from its massive natural gas reserves, estimated to be the world’s fourth largest by volume, have caused massive wealth to flow into the country.

A map of Turkmenistan showing surrounding countries

Geography and Demographics

The Karakum Desert covers about 80% of Turkmenistan, dominating the country’s flat, arid center. The country’s few mountains, grouped along its borders, receive enough rain to support grasslands and some forests. However, the mountains are not high enough to maintain the snow caps that create significant river systems. Thus, Turkmenistan has only one major river, the Amu Darya. Two other minor rivers, the Murghab and the Tejen, also provide irrigation, but are not large enough to provide transport routes. Even with several man-made canals, dams, and irrigation projects, only 4% of the country is now cultivated.

Turkmenistan’s land has never supported large populations. Although about 15% bigger than the US state of California (164,000 square miles vs. 189,000), its population is less than 15% of California’s (38 million vs. 5.25 million).

Most live along the comparatively well-watered borders. One fifth lives in the three largest cities: Ashgabat (the capital), Dashoguz, and Turkmenabat (both industrial cities and transport hubs). Turkmenbashi, on the land-locked Caspian Sea, is the country’s only port. Russian minorities are concentrated in Turkmenbashi and Ashgabat. Uzbek minorities are concentrated along the Uzbek border.

Despite its many challenges, Turkeminstan’s economy is one of the world’s fastest growing. GDP rose from 2.3 billion in 2000 to nearly 42 billion in 2013 as the price of natural gas and oil rose and as Turkmenistan built new pipelines to seek the highest price for its exports. The government also supported textile production, large-scale irrigation, and mandated production of export crops such as cotton and grain. The population rose with the economy from 4.5 million people in 2000 to 5.25 million today.

This satellite image of Turkmenistan clearly shows the dominance of the Karakum Desert (yellow and white) and the scarcity of agricultural lands and forests (green). We’ve additionally marked Turkmenistan’s five major cities to show how geography has shaped the country. For the original (larger) image, click here.

Early History

Humans have inhabited areas of present-day Turkmenistan for at least 8,000 years. The earliest evidence of agriculture in Central Asia was discovered at Jeitun, an archeological site some 20 miles north of Ashgabat.

The earliest inhabitants were Iranian tribes, including the Scythians, a nomadic, equestrian warrior people that greatly influenced civilizations across Eurasia, including the Russians. Turkmenistan was to be found in the northeast of all the Iranian empires, including the Medians, Persians, Parthians, and Sasanians. Although conquered by Alexander the Great and ruled for a time by the Hellenic Seleucid Empire, Turkmenistan spent much of its history connected to the empires of the Middle East.

Ethnically, the Turkmen come from the Oghuz, tribes of Turkic-speaking peoples who came to Central Asia from present-day Mongolia and southern Siberia in the 8th century AD. Over several centuries, they spread through Central Asia and east to Turkey. Turkmen tribes were based on patrilineal descent, lived by nomadic pastoralism, and used moveable shelters called yurts.

The Seljuk Empire, with its capital in modern Iran, once dominated the land from Turkey to Kyrgyzstan. We have highlighted the borders of modern Turkmenistan in black. For the original (larger) image, click here.

In the 10th century, Islam became the tribes’ dominant religion and the term “Turkmen” was first used. “Turkmen” means either “resembling a Turk” or “pure Turk,” (there is some dispute about the origin of the suffix). By the 11th century, the tribes united to found the Seljuk Empire, which was Turkic, but adapted to the local Iranians, creating the Turko-Persian tradition that would later thrive under the Ottoman Empire. To this day, the Turkmen and Turkish languages have a high degree of intelligibility.

At the time, the largely Iranian population was based around the Amu Darya River. The Seljuks settled several oases as well, and by the 12th century, many of these cities were enjoying a golden age under the Khwarazmia, a Persian empire that grew wealthy from the Silk Road.

The 13th century Mongol conquest was particularly bloody. Many cities were razed and whole populations slaughtered when their rulers defied the Mongols. Over several generations, the population recovered, although the golden age was not to be repeated. When the Mongol empire split, most of modern-day Turkmenistan fell under the Khiva khanate, which was then contested between the larger powers of Britain, Russia, and Persia.

Russian Empire

Russia made incursions into Turkmen territory from at least the 18th century. These included armed commercial expeditions to claim gold deposits as well as operations to free Russians captured and sold into slavery by Turkmen traders. It also was during this time that a conception of a single Turkmen nation started to take hold. Local scholars began to record the epic poems sung by the Turkmen for centuries and urged cooperation and peace between the various, often fractious Turkmen tribes.

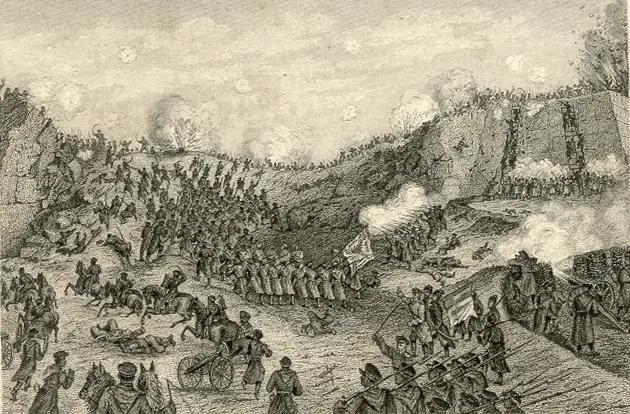

Russian engraving of the storm of Goek Tepe.

Russia annexed the territory in the late 19th century in a decisive and bloody campaign. In 1881, for instance, General Mikhail Skobelev led Russian forces in a 23-day siege of the Goek Tepe fortress. About 14,000 Turkmen civilians and soldiers were killed, many while fleeing into the desert from the pursuing Russian cavalry. After areas were conquered, Russian raids to stamp out resistance often continued.

The conquest was accompanied by infrastructure to solidify Russian claims. The Transcaspian Railway was constructed as the army advanced, improving mobility. The Caspian Sea port of Krasnovodsk (present day Turkmenbashi) was built to improve naval capabilities. Ashgabat was founded at a strategic location near the border with Persia, which was controlled by the British at the time. Ashgabat became the capital of the Transcaspian Oblast when annexation was completed in 1885.

Slavic migration grew significantly; towns were established and expanded along the growing Transcaspian Railway, and the oblast’s cotton export to Russia increased from 300 tons in 1890 to 64,000 tons in 1913.

In 1916, the native populations rebelled. The shift to cotton production, along with the influx of settlers, left many Turkmen without land while facing high food prices and war taxes as Russia fought WWI. In this climate, a June decree to mobilize previously exempt Central Asian Muslims led to riots. Russian and Cossack forces countered these, and thousands of Turkmen fled the empire to Iran and Afghanistan.

Soviet Union

Following the 1917 revolutions, what had been anti-conscription protests evolved into the Basmachi Movement. “Basmachi” was a term used for bandits, and it was applied by the Soviets to Central Asians who resisted Soviet rule. This was actually a number of separate movements, in which Turkmen, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Uzbek forces fought the Soviets, usually with the ultimate goal of establishing independent nations for their separate peoples. The Turkmen were led by Junaid Khan, based in Khiva (present day Uzbekistan) until 1925, when he retreated to Afghanistan with his supporters.

The Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic was formed in 1924, when the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, established in 1918, was divided along ethnic lines. The Soviets secured the borders with Afghanistan and Iran to prevent further emigration and to prevent Basmachi fighters from returning.

With industrialization and forced agricultural collectivization, by the late 1930s, the traditionally nomadic Turkmen were mostly sedentary for the first time. Irrigation measures fostered the production of fruits, vegetables, and cotton, changing the desert landscape.

Although Turkmenistan is small and sparsely populated, it has massive natural gas deposits.

On October 6, 1948, a powerful earthquake shook Ashgabat, killing about 110,000 – two thirds of the city’s population, and 10% of the population of the Republic. The earthquake orphaned the future president, Saparmurat Niyazov, and is now memorialized by an annual, national day of mourning.

In the 1940s and 50s, large natural gas deposits were found in the Turkmen SSR, and by the 1980s, the republic was the USSR’s second largest gas producer after the Russian SSR. Gas was exported mostly to other Soviet Republics, but also soon powered new industry, especially under the post-WWII reconstruction efforts. Russians and Ukrainians migrated to the republic in greater numbers to fill the jobs created by these factories.

Changes in daily life under the Soviets were great. The Turkmen SSR became the USSR’s top cotton producer. The enormous Karakum Canal was begun in the 1950s to carry water from the Amu Darya to Ashgabat and to the irrigate cotton. Both primary and secondary education was compulsory by 1959, the Turkmen language was standardized, and literacy officially reached 99% by 1970. The country’s once thriving Muslim community was repressed, and only five mosques still functioned for the entire country in 1991. Active resistance to Soviet rule was stamped out under Stalin’s purges.

In December 1985, Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev replaced longtime Turkmen first secretary Muhammetnazar Gapurov with Saparmurat Niyazov. However, under the conservative Niyazov, Gorbachev’s reforms barely touched the Turkmen SSR. In 1990, Niyazov became Chairman of the Turkmen Supreme Soviet, and then the Republic’s first president. Turkmenistan declared independence from the crumbling Soviet Union on October 27, 1991 – one of the last countries to do so.

Post-Soviet Turkmenistan: Turkmenbashi

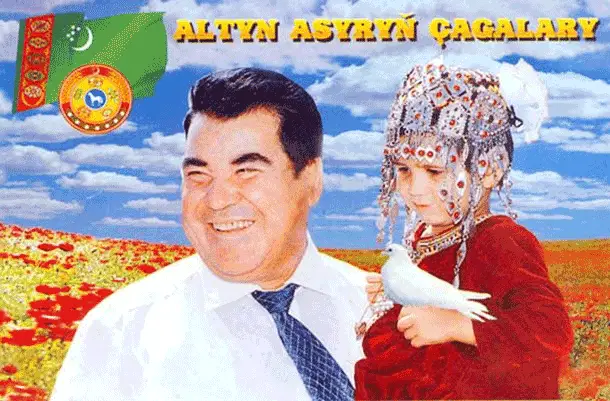

Post-Soviet Turkmenistan has been defined by the autocratic presidency of Saparmurat Niyazov, who ushered in what he called “Turkmenistan’s Golden Age,” a term the nation continues to use.

A billboard showing Saparmurat “Turkmenbashi” Niyazov holding a child in Turkmen dress.

Niyazov renamed the Communist Party the “Democratic Party of Turkmenistan,” and, with no opposition, won over 99% of the vote in 1992. His 1992 constitution established an officially secular, democratic republic, but with all branches of government subordinate to the president. Even the Council of Elders (Mejlis), which would select presidential candidates, was presided over by the president. In 1999, constitutional amendments allowed Niyazov to be named Turkmenistan’s president for life.

Niyazov took the name Turkmenbashi, or “Father of all Turkmen” and moved to establish a Turkmen identity distinct from the Soviet or Russian identities. Turkmen became the sole language of the state and all educational instruction. Numerous holidays were introduced such as a Memorial Day for the Battle of Goek Tepe and several celebrating pre-Soviet national figures and traditional culture.

Niyazov created a cult of personality. His portrait could be found nearly everywhere and a 39-foot gold statue that revolved to face the sun was installed in the capital’s center. He renamed the port city of Krasnovodsk “Turkmenbashi.” Names of days, months, and foods were changed to honor himself and his family.

Niyazov also wrote the Ruhnama, a sweeping book featuring his autobiography, poetry, and opinions on morality and government. It was quoted alongside the Quran on the walls of mosques and knowledge of its teachings was tested in schools, during job interviews, and even driver’s license exams. At the same time, libraries were closed and funding for public education was cut as Turkmenbashi felt that all useful knowledge could be found in the Koranand Ruhnama.

Two of the many, many gold-colored statues to Saparmurat “Turkmenbashi” Niyazov that can now be found in Turkmenistan.

By 2002, enrollment in higher education had dropped by almost half since 1991. Meanwhile,hospitals were closed, pensions were cut, independent news media closed, travel and internet restricted, and children were conscripted to pick cotton to help meet state agricultural goals. Political dissent was harshly punished, with measures strengthened after a 2002 assassination attempt on the president.

Despite this, Niyazov’s economic policies are generally credited for laying the groundwork for Turkmenistan’s current economic growth. Niyazov expanded irrigation projects and used the country’s gas wealth to diversify the economy, allowing Turkmenistan to process most of its oil, gas, and cotton products before export. That said, wealth remained centralized: high-paying jobs were mostly in the upper levels of government and most production was controlled by those close to the government. Like all post-Soviet nations in the 1990s, the country faced unemployment, poverty, and economic instability. Turkmenistan’s oil and gas wealth, however, meant that the government could supply citizens with free gas and water, cheap electricity, and significantly-subsidized housing – luxuries unavailable to most suffering through that time.

Niyazov’s 1995 Declaration of Permanent Neutrality has given Turkmenistan an internationally-recognized status similar to Switzerland: Turkmenistan has pledged not to join military alliances or fight offensive wars. This has been hailed as a way to advance peace in Central Asia, to keep Turkmenistan separated from international disputes, and to keep state spending focused on the economy rather than the military. It has also been criticized as another way to keep Turkmenistan isolated from the international community and thus under absolute presidential control.

Modern Turkmenistan: Berdimuhademow

After Niyazov’s sudden death of a heart attack in 2006, his former dentist, minister of health, and close associate, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, was named acting president and subsequently won the 2006 election with 89% of the popular vote. He was reelected in 2012 with 97% (the other candidates, all of the same party, praised the incumbent in their campaigns). His presidency has been a mix of maintaining tight presidential control while rolling back more extreme policies.

Berdimuhamedow shown in traditional Turkmen dress atop an Akhal-Teke horse.

Berdimuhamedow has dismantled much of the Niyazov personality cult. He has returned the days of the week and months to their original names and moved the giant statue of Niyazov to the city outskirts. He has developed his own smaller cult of personality, however: he is called Arkadag (“protector”), has disseminated his own books, associated himself with the revered native Akhal-Teke horse breed, and has approved plans for a statue of himself to be erected in the capital. Portraits of himself have been disseminated to replace those of Niyazov.

Many problems of the Niyazov era continue. Corruption, poor economic freedom, and pressure maintained on the press remain complaints of the opposition. Children continue to harvest cotton. Also, religious groups must meet membership quotas for government registration. This has effectively banned all but Islam and Orthodoxy in Turkmenistan. The police and intelligence services monitor the population closely and physical affection such as hand-holding and kissing in the capital are forbidden.

Berdimuhamedow has largely maintained the economic policies of his predecessor. While Turkmenistan was once dependent on Russia as its only export route for its massive natural gas reserves, pipelines to China and Iran have been completed under Berdimuhamedow. He has also negotiated to provide Europe with natural gas directly via a proposed connection to the proposed Nabucco pipeline. China is now Turkmenistan’s largest natural gas customer. Additionally, Turkmenistan is the world’s ninth largest producer of cotton and produces grains, melons, and pistachios for export.

Some construction investments, however, have been more for show than utility. The major cities have whole streets of upper class housing that remain largely empty. Ashgabat now holds the world record for the highest concentration of marble buildings. Berdimuhamedow built a massive new presidential palace to replace the one built recently completed by his predecessor. The Alem Cultural Center in the city, completed in 2012, houses the world’s largest enclosed Ferris wheel. A 380-acre market was built outside Ashgabat in 2011 to resemble, from above, an enormous traditional Turkmen carpet. Despite all this, foreign visitors have described Ashgabat’s newly developed downtown as largely empty of people.

Turkmenistan has maintained close relations with Iran, a country that it shares cultural and historical connections with – as well as hydrocarbon-richness. Here, Turkmen leader Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow is shown with former Iranian leader Mahmoud Ahmedinajad.

Berdimuhamedow has expressed interest in growing Turkmenistan’s tourism industry and has built many upscale hotels, especially in Ashgabat and Turkmenbashi. However, these hotels remain largely empty. Tourists must be guided through the country, and photography in public places is strictly controlled by police. Turkmenistan currently receives only 12,000-15,000 tourists per year, mostly from other former Soviet states.

Turkmenistan is facing significant environmental issues, stemming mostly from Soviet-era agricultural projects, and current lack of regulation. The Amu Darya delta is an agricultural hub, but damming and irrigation have kept it from sufficiently replenishing the Aral Sea. The Aral Sea has been shrinking by large degrees, and has become increasingly polluted. In addition, the Karakum Canal was poorly constructed, allowing about 50% of all water to escape before reaching its destination. In addition to being wasteful, this has led to a rise in the ground water table, pushing up salt from beneath the soil, helping the Karakum Desert to expand, and thus potentially threatening Turkmen agriculture.

Interestingly, Turkmenistan has moved to counter this largely through the construction of man-made forests and a massive man-made “Golden Age Lake” in the northern Karashor Depression. Theoretically, these efforts are meant to terraform Turkmenistan, changing the local weather and ecology.

Turkmenistan is full of contradictions. Its nationalism, rooted in native Turkmen culture, is imposed by a Soviet-style regime. Its mostly poor citizens reside on immense, subterranean wealth. Despite its small population and human rights record, Western democracies court it, seeking access to Turkmenistan’s natural riches. The more its land is used to generate wealth, the more the land itself has fallen into decline. Despite the country’s extreme isolation and secrecy, it has become increasingly visible. This still-young, and seemingly both unsustainable and unshakeable nation, will be one to watch in the decades to come.