The memory of the Holodomor has become integral to modern Ukrainian identity. Having lived through that tragic and horrible event as a nation, it is now part of the national consciousness, proof of the persistence and strength that many Ukrainians hold up as a proud part of who they collectively are. The state has also supported this remembrance through the speeches of its leaders, as well as through legislation, court rulings, and the foundation of the Holodomor Museum in Kyiv. This essay will analyze the modern political discourse behind the commemoration of the Holodomor and the role of Ukrainian leaders in that discourse.

President Yushchenko Lays the Foundation

Former president Viktor Yushchenko has played an important role in Ukrainian state-building by advocating for strong democratic institutions and European integration. He has also played a significant role in exposing the atrocities committed during the famine.

While president, Yushchenko created a strong platform for the remembrance and commemoration of the Holodomor. On November 8th, 2006, Yushchenko wrote the “Про Голодомор 1932-1933 років в Україні” (The Law of Ukraine about the Holodomor 1932-1933) which recognized the famine as genocide, outlawed Holodomor denial, and mobilized government resources to commemorate the famine.[1] The law advocates for Ukraine and the world to be educated about the Holodomor. Perhaps more importantly, it also calls for a uniting national awareness of the event among Ukrainian citizens. The law decrees a “moral obligation to the past and future generations of Ukrainians and recognizing the need to restore historical justice, establishing in society intolerance to any manifestation of violence.”[2] The law thus emphasizes a responsibility on the part of Ukrainians, as a nation, to pursue justice against the Holodomor’s perpetrators to honor the victims of the famine and to prevent any reoccurrence of such violence.

Nation building is written directly into the stated goals of the law, which is to “promote the consolidation and development of the Ukrainian nation, its historical consciousness and culture, the dissemination of information about the Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine among the citizens of Ukraine and the world public, to ensure the study of the tragedy of the Holodomor in educational institutions of Ukraine”.[3] Through this law, Yushchenko seeks to incorporate awareness and education of the Holodomor into a Ukrainian sense of national identity and thus, state building.

The law reflects the rhetoric Yushchenko used throughout his presidency. On November 25, 2006, now honored as Holodomor Remembrance Day, Yushchenko gave a speech honoring the victims of the famine. He stated, “those who today deny the Holodomor are filled with deep and adamant hatred for Ukraine. They hate us, our spirit, our future. It is not history that they deny, it is Ukraine itself”.[4] Here, Yushchenko takes an additional step, establishing the memory of Holodomor as something that not only defines Ukrainian identity, but also its antithesis.

This two-sided perspective adds pressure to the Ukrainian population to conform to his understanding of Ukrainian national identity or risk being excluded from it and, worse, included with what he has defined as anti-Ukrainian. He again emphasizes an obligation on the part of Ukrainians to honor those who fell victim to the Holodomor and condemns the perpetrators of the genocide. Furthermore, he sets a more rigid standard of true Ukrainian identity, accusing those who do not fit that standard as being anti-Ukrainian.

The Ukrainian Justice System Furthers the Cause

The Kyiv Court of Appeal took an additional step in 2010 to define what “anti-Ukrainian” means, using Stannislav Vikentivevich Kossior and Vlas Yakovovich Chubar, the main perpetrators of the Holodomor, as illustrations. These historical personages are held up in the ruling as a personification of the suppression of Ukrainian identity.

In that year, the Kyiv Court of Appeal convicted Kossior and Chubar of genocide posthumously. Kossior was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine at the time[6] The resolution finds its judgement on the basis that the two men instituted harsh grain and seed requisition “in spite of starvation in Ukrainian villages,” of which they had to have known about at the time.[7] Furthermore, the Court stated that the “Bolshevik regime undertook active measures on its territory intended to prevent the restoration of an independent Ukrainian state” to establish a “communist rule” and suppressed “any parties and movements that supported the idea of Ukraine’s independence.”[8] The Court stated that these men (among others) “began an all-encompassing forced collectivization of agriculture, deportation of Ukrainian peasant families, unlawful confiscation of their property, repressions and the physical destruction of Ukrainians” and “adopted the decisions, and artificially created the conditions […] to exterminate, by famine, a part of the Ukrainian nation.”[9] To support its argument of genocide, the Court uses the idea that forced collectivization deprived people of food in spite of ongoing starvation.

The ruling played a significant role in legitimizing Ukrainian nationhood on an international level. The court specifically cites its jurisdiction by stating that: UN “Article VI of the Convention, ‘On the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide’, dated December 9, 1948, also provides that ‘persons charged with genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III, shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory of which the act was committed’”[10]. This reference to international law allowed Ukraine to exercise its sovereignty as an independent nation to convict these men which it could not do under repressive Soviet

The Holodomor Museum Coalesces History and Identity

The Holodomor Museum was founded on the idea of warning society against “repeating the crime of genocide by accumulating and spreading knowledge about the Holodomor” and to “remind people of the Ukrainian identity that was attempted to be replaced by the Soviet one”. [11] It works to research, collect, and curate data on the Holodomor to inform the public about the famine. In addition to permanent exhibitions and expositions, the museum also hosts conferences and various forms of public outreach to prevent further denial of the Holodomor, “which can be heard from the Russian Federation, an extension of the USSR.”[12] The museum materializes Yushchenko’s, the Kyiv Court of Appeal’s, and the Ukrainian Rada’s rhetoric towards the Holodomor.

The Holodomor Museum contains Yushchenko’s quotes and the 2010 ruling against Chubar and Kossior. It builds on these additionally, for example, to represent the Holodomor’s individual victims in a way that also constructively fosters Ukrainian unity around this national trauma. a project that collects individual eyewitness testimonies, and maps then online, publicly showing that the trauma was truly national and experienced over the full territory of Ukraine.[13]

In one of these testimonies, Tatyana Kostyantynivna Dyachenkostory shares her mother’s story that reflects a continued sense of humanity during the tragedy. Her mother lived in the small village of Yurkivtsi in what is now western Ukraine. Tatyana describes her mother and family as suppressed, hungry, and even enslaved. In her testimony, she recounts that another family took her “grandfather and [mother] to their house and never complained, because they themselves lived in poverty and wanted to help someone”.[14] This testimony shows a sense of solidarity between Ukrainians that endured during times of repression. The resiliency reflected in the story serves as source for the empowerment of the Ukrainian national experience.

Another story by Hvnativna Valentina Nechyporuk normalizes the enduring trauma from the Holodomor and argues for its continued memory. Born on an apiary in a village called Luka, near Kyiv, Nechyporuk recalls that she was fed honey every day as other food ran out. She says “I didn’t like honey and I don’t like it now. They gave it to me like that”. Her granddaughter added that her “grandmother told me that she ate a lot of it then and doesn’t eat it anymore”. [15] Her dislike for honey serves as a manifestation of the trauma that the Holodomor caused. She additionally states that “Children also need to be told. They don’t remember such a thing, they won’t remember it, but they have to be told.” Thus, she also furthers the idea that the history needs to become something remembered collectively for generations to come.

Conclusion: Holodomor as National Discourse and an Identity Marker

Remembrance of the Holodomor not only serves to honor those who passed during the famine, but also continues to motivate political discourse. Yushchenko used the Holodomor remembrance to help define Ukrainian identity. Additionally, the Ukrainian justice system used the trial of Chubar and Kossior, in part, to make an international statement about Ukrainian statehood and independence. Lastly, the Holodomor Museum uses testimonies from survivors to highlight a resiliency and other positive character traits that can be seen across the nation. All of this helps solidify a concept of Ukrainian national identity within a shared experience of trauma.

Works Cited

“Profile: Viktor Yushchenko.” January 13, 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4035789.stm.

Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України. “Про Голодомор 1932-1933 років в Україні.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/go/376-16.

Human Rights in Ukraine. “President Yushchenko: On Remembrance Day for the Victims of Holodomor.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://khpg.org//en/1164484154.

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide. “Resolution of the Court,” October 16, 2019. https://holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/resolution-of-the-court/.

Місця масового поховання жертв Голодомору-геноциду. “Місця масового поховання жертв Голодомору-геноциду.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://map.memorialholodomor.org.ua/testimony/rybak-oleksandra-petrivna-1926-r-n/.

Місця масового поховання жертв Голодомору-геноциду. “Місця масового поховання жертв Голодомору-геноциду.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://map.memorialholodomor.org.ua/testimony/nechyporuk-valentyna-gnativna-1926-r-n/.

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide. “About the Museum,” September 11, 2019. https://holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/about-the-museum/.

Footnotes

[1] “Про Голодомор 1932-1933 років в Україні,” Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України, accessed April 8, 2024, https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/go/376-16.

[2] ibid

[3] ibid

[4] “President Yushchenko: On Remembrance Day for the Victims of Holodomor,” Human Rights in Ukraine, accessed April 8, 2024, https://khpg.org//en/1164484154.

[5] “Ruling in the Criminal Proceedings over Genocide in Ukraine in 1932-1933” (2019), https://holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/resolution-of-the-court/.

[6] ibid

[7] ibid

[8] ibid

[9] ibid

[10] ibid

[11] “About the Museum,” National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, September 11, 2019, https://holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/about-the-museum/.

[12] ibid

[13] “Місця масового поховання жертв Голодомору-геноциду,” Місця масового поховання жертв Голодомору-геноциду, July 4, 2019, https://map.memorialholodomor.org.ua/golodomor-1932-1933/.

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

You Might Also Like

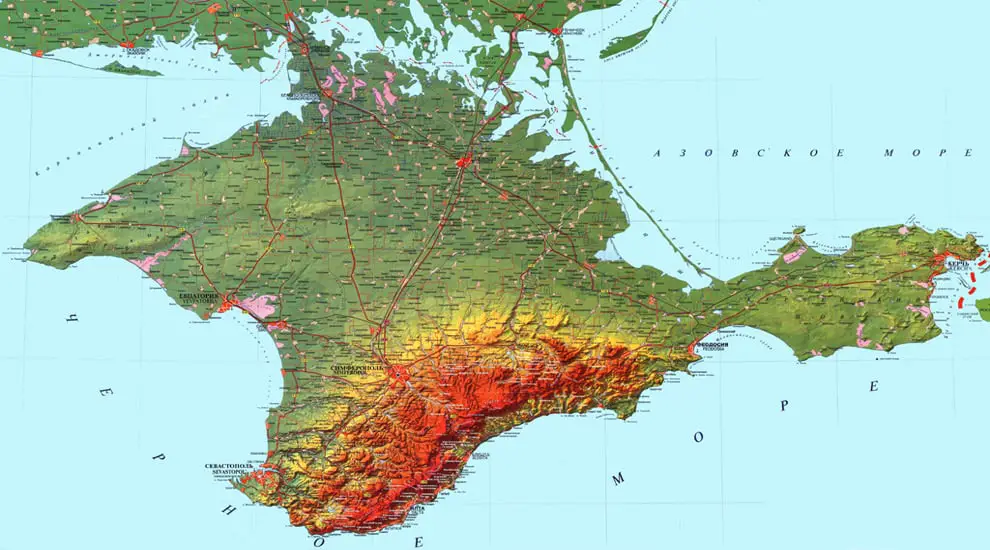

Russian MiniLessons: Крым: хронология событий – A Crimean Timeline

The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal…

On the Eve of Crimean Independence

The day before Crimea voted in its independence referendum, The Village, a Moscow-based publication with editions in St. Petersburg and Kiev, asked residents of various…

From Vixen to Victim: The Sensationalization and Normalization of Prostitution in Post-Soviet Russia

Since the height of its popularity in the mid-1990s, the Moscow nightclub “Golodnaya Utka,” or “The Hungry Duck,” has been dubbed “Moscow’s first rape camp.”[1]…

The Rediscovery of the “Russian World”

During the last few weeks, the term “russkiy mir,” which can roughly be translated as “Russian world,” suddenly gained increasing prominence. It became the center…

Kiev: At the Center of a Divided Country

The ancient city of Kiev continues to thrive as the most populous city of Ukraine. Much like other post-Soviet capitals, Kiev’s future looks bright, despite…