The ancient city of Kiev continues to thrive as the most populous city of Ukraine. Much like other post-Soviet capitals, Kiev’s future looks bright, despite the global economic crisis and growing concern about corruption. While Kiev is probably best known for its historical connection to the Old Rus’ polity, a historical predecessor to the modern Russian state, Kiev is an important modern center for industry, education, and culture for not only modern-day Ukraine, but all of Eastern Europe.

Topographic map of Ukraine. Kiev is located in the center north.

History of Kiev

Exactly when the city was founded is also a subject of debate. Most historians date the city to the 5th century, but some hypothesize that the area was not really settled until the 6th century. Some have argued that the founding occurred much later, closer to the 8th or 9th centuries, but archeological evidence has largely disproved this.

What can be said with relative certainty is that the city only began to develop into a center of regional importance in the late 9th centry. It was then sized by the Varangians from the Khazars, who had built a fortress there.

The Varangians were a Baltic people associated closely with the Vikings. However, the particular Varangians who took Kiev were known as the “Rus'” and were led by Oleg of Novgorod. Novgorod, at the time, was the capital of the Rus’ polity and a flourishing trade center servicing the lucrative trade routes from the Baltics to Constantinople which the Vikings and Varangians dominated. Oleg moved his capital from Novgorod to Kiev and the military settlement of Kiev soon became a regional center for commerce and culture.

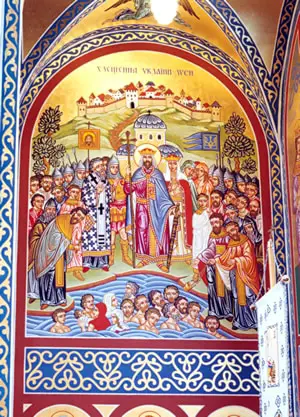

In 988, Prince Vladimir the Great introduced Christianity as the religion of the realm from his seat in Kiev. Legend states that Vladimir initially considered Christianity along with Judaism and Islam as state religions, but rejected the latter two due to their bans on pork and alcohol (two staples of Kievan Rus’). However, there were also political consequences to Vladimir’s decisions. The famed “Baptism of Rus’” firmly cemented the polity’s alliance with the Byzantine Empire. In addition, Vladimir based the new church in Kiev and structured it around himself, giving him not only political authority, but now religious authority over the Rus’ people.

The Babtism of Rus’ is a frequent subject of art in Russian and Ukrainian culture. This icon is located inside St. George’s Ukrainian Catholic Church, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

In 1240, the city was besieged and destroyed by the invading Mongols, led by Batu Khan. Kiev and the surrounding land, which are highly fertile, positioned on lucrative trade routes, and generally flat and navigable, now saw how this combination can be a recipe for success, but also an combination too tempting for invading armies to pass up.

For the next 400 years, the city was was passed between multiple empires. In 1362, Kiev became a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, after the Golden Horde Mongolian army suffered a defeat at the hands of the Grand Duke. Later, the city and surrounding area were transferred to Poland as part of the Union of Lublin, an alliance that created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569. However, political differences led to hostilities between Ukraine and Poland and, in 1654, Ukraine and Russia signed the Treaty of Pereyaslav in which Ukraine pledged allegiance to Russia in return for Russian military help against the Poles. Kiev was still claimed by Poland, however, and would be ceded to Russia only in 1667.

As part larger empires, and especially during its early days as part of the Russian Empire, Kiev played a marginal role in terms of commerce. During the 18th and 19th centuries, Kiev’s religious, cultural, linguistic, and economic institutions were increasingly influenced and altered by Russia’s military and ecclesiastical concerns and the city was largely Russified by the end of the 19th century.

Ukrainian nationalism, however, developed in underground political societies during this period, in part in reaction to the Russification that was occurring. This movement was of major concern to the Tsar and was ruthlessly repressed. In large part, this repression only served to push the movements further underground and further radicalize its members.

During Russia’s industrial revolution during the 19th century, Kiev again became an important trade and transportation hub – now by both rail and river. Kiev was a major export point for the massive amounts of grain and sugar produced by Russia. It was also populated by a number of successful merchants and artisans, whose number included heavy amounts of Jews, who helped build many of the city’s important landmarks from theatres to synagogues.

The People’s Friendship Arch is one of many Soviet-era monuments in Kiev dedicated to celebrating the union of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples and states. Part of the surrounding sculptures are dedicated to depicting the signing of the Treaty of Pereyaslav.

During the Russian Revolution of 1917 and WWI, control of Kiev shifted between governments led by the various Soviet, Anti-Soviet, and Nationalist parties. The city would also see its government shift a total of sixteen times from 1918 to 1920 as Ukraine first declared independence after the revolution and then was occupied by various invading forces.

Finally, in 1921, Kiev became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Yet, the previous years of turmoil had greatly damaged Kiev. Despite Kharkiv being named the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, a massive restoration of Kiev’s economic and cultural life took place on the basis of reviving its industrial capacity; under Soviet industrialization, Kiev became a new center of industry, science, and technology. However, while it benefitted from Soviet policies, it also suffered under them as Kiev would, like the rest of Ukraine, be decimated by The Great Famine of the early 30’s and, later, Stalin’s purges. In 1934 Kiev became the capital of Soviet Ukraine, and period of dramatic economic development ensued.

In 1991, with the fall of the USSR, Ukraine declared its independence. Like many other post-Soviet states, Ukraine suffered a deep recession in the 1990’s as its economy struggled to transition to capitalism and its government experimented with new governing techniques. The economy eventually stabilized in the 2000’s, but is still struggling. Politically, Kiev was the center of the Orange Revolution, which saw 500,000 people took to the city’s streets to protest the 2004 presidential elections, in which Viktor Yanukovych had been declared the winner amid widespread evidence of electoral fraud. Ironically, Ukrainians as a whole elected Yanukovych back into office in 2010. However, Kiev has remained largely “orange” and liberal, with more than 60% of Kievan votes going to one of the Orange Revolution’s figureheads, Yulia Tymoshenko.

The Kievan Economy and Population Today

While Ukraine’s population has declined in the post-Soviet era, Kiev’s total population has grown, thanks largely to its relatively stable economy. Like the rest of the world, Kiev was hit by the financial crisis of 2007-08, losing 13.5% of their gross regional product. However, this is 1.6% less than the national average that Ukraine lost during the same period.

Kiev’s economy today dominated by large energy companies and, as such, is heavily tied to Russian interests and hydrocarbon supplies. Utilities, including electricity, gas, and water, make up the 26% of the city’s industrial output. In 2008, Naftogaz Ukrainy, one of the largest natural gas importers in Ukraine, based in Kiev, made a deal with Russia’s natural gas monopoly, Gazprom, in which it was stipulated that Naftogaz would be the sole importer of Gazprom gas.

Mother Motherland is a 335-foot statue in Kiev. It is part of the city’s massive WWII museum complex.

Kiev’s other primary industries are also largely inherited from its Soviet past. The manufacture of food and beverage make up 22% of Kiev’s total industrial output, chemical and mechanical engineering takes another 30%, and the manufacture of paper and paper products takes 11%.

Today, services and particularly IT outsourcing are also beginning to make their mark on the city. In May of 2011, the Kiev authorities presented a 15-year plan for the city’s economic development which forsees the city focusing on engineering and high-tech industries and drawing as much as 82 billion Euros of foreign investment into these sectors.

Modern Culture in Kiev

Given its turbulent history and frequent occupation, Kiev, like the rest of Ukraine, can be said to have issues with its self-identity. Of its 2.7 million inhabitants, only 24% speak solely Ukrainian in their households, according to a 2006 survey. Nearly 52% percent speak primarily Russian at home, and that number rises the closer one gets to the city’s economically powerful center. Interestingly, although Russian is the lingua franca of the city, Russians only account for 13% of Kiev’s population. Approximately 130 different nationalities and ethnicities make up the other 87%.

Kiev’s cultural life is rich and diverse. The city’s Slavic architecture, including ancient monuments and cathedrals, clearly represent Kiev’s ancient history and enduring spirit. Two of Ukraine’s “Seven Wonders” reside in Kiev. One of these is the Saint Sophia Cathedral (Собор Святой Софии), which was built in the 11th century. Named after an ancient cathedral in Constantinople, it was in this cathedral where centuries of Kievan princes were crowned in the polity’s golden age. The second “wonder” is Kiev’s Pechersk Lavra, or “Monastery of the Caves.” The monastery is a historic orthodox Christian attraction consisting of soaring bell towers, beautiful cathedrals, and underground caves that were also used as an important outpost of Kiev’s resistance movement during WWII.

Independence Square in Kiev now commemorates Ukraine’s 1991 declaration of independence from the USSR. It was also the major site for the protests that drove the Orange Revolution in 2004-2005.

Kiev is also littered with note-worthy museums and theatres. One such museum is the Museum of the Great Patriotic war, which documents the victory in World War II as well as its devastating cost in lives. Visiting this museum, one gets a true understanding of Ukraine’s sacrifice during those horrendous times. The city also abounds in art museums and theatres, including the National Art Museum, the Pinchuk Art Center, and the Kiev Opera House. The National Art Museum’s current collection consists of over twenty thousand pieces, including works by famous Ukrainian and Russian artists. Many theaters perform in Russian and Ukrainian. The Kiev Opera House, established in 1867, continues to please audiences with various operas and a broad repertoire of ballets.

While Kiev’s fate has been largely decided by non-Ukrainians, today’s Kiev, with its high-tech industry, higher education institutions, and famous landmarks, is one of Eastern Europe’s most important industrial, scientific, and cultural centers. Kievans, strong-willed and determined, will undoubtedly continue along their country’s chosen path of democracy and capitalism. Perhaps someday Kiev will be less known for its role in Russian history and more for its part in establishing Ukraine as an independent nation.

Find Out More About Programs in Kiev, Ukraine