Estonia is a mostly flat, small country, two thirds of which is covered by forests and marshlands. Its strategic location on the northern Baltic coast and its several natural ports and islands make it pivotal to controlling sea routes through the Gulf of Finland and the larger Baltic Sea.

Estonia’s history is one of several centuries of domination by empires, including by Germans, Swedes, Russians, and Soviets. Sovereign briefly from 1920-1939, its current independence came with the collapse of the USSR in 1991. Since then, Estonia has emerged as a republic eager to forge its own path in Europe. It has the highest nominal GDP and PPP per capita out of any ex-Soviet state and has become a model for digitizing state and commercial services.

Because of its history, Estonians place a high value on preserving and supporting their linguistic and cultural heritage. Folk song, traditional dance, and Estonian literature are particularly beloved. Ensuring that all Estonian citizens can speak Estonian has been a significant point of friction with Estonia’s large ethnic Russian minority and with neighboring Russia, considered by most Estonians to be the country’s biggest security threat.

Despite its small size, Estonia plays an important role in European defense policy and cybersecurity initiatives. It has a strong and growing economy, but is also export-dependent and has faced challenges like high inflation and slowing external demand.

Introduction to Estonia: Geohistory

Estonia is a country shaped by water. The Gulf of Riga and Gulf of Finland flank the country to the north and west while the freshwater Lake Peipus dominates Estonia’s eastern border. All of the county’s most important cities are ports. Tallinn and Pärnu face the Baltic Sea while Narva and Tartu are river ports servicing inland traffic. The Baltic’s longstanding and lucrative trade routes have left Estonia with strong cultural and economic ties to Scandinavia and Germany.

Estonia can be roughly divided into two biospheres. The western and northern regions, including the large islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, are marshy and challenging to develop agriculturally. Conversely, the drier central and southern regions are more arable and fertile.

- Topographic map of Estonia highlighting rivers and roads. The country’s highest peak reaches only about 70% of the Empire State Building’s height above sea level.

- Estonia land use in 2019. “Artificial surfaces” indicate major urban areas.

More than 90% of Estonia is less than 100 meters above sea level. Tallinn, Tartu, and Narva were built on three of the country’s few strategic hills which provided attractive defensive positions along its trade routes.

Estonia’s chief natural resources are oil shale, which contributes about twenty percent of the nation’s GDP, and timber, which adds another ten. Its flat terrain and long coastline create considerable winds, which have been harnessed in recent years to supply over a quarter of domestic electricity. Estonia aims for full energy independence through renewables by 2030. With few other extractable resources, aside from deposits of construction materials and newly discovered magnetic rare earth oxides, the country has emphasized technology and service-sector growth in its economic policy.

Estonia is only about half the size of the US state of Maine, with a comparable population of 1.3 million. About 70% of that population is ethnically Estonian with Russians (~20%) and Ukrainians (~5%) forming the largest minorities. The Russian population has steadily declined since independence, partly because a 1993 law requires residents whose families arrived after 1940 to demonstrate Estonian-language proficiency to obtain citizenship. Due to this policy, roughly 5% of Estonia’s residents are stateless, mostly ethnic Russians. Meanwhile, since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, around 40,000 Ukrainians have settled in Estonia, increasing the population by about 3%.

Meadows cultivated into forests for agricultural use, often adjoining lakes, marshes, or marshy forests, are common sights on the Estonian landscape.

Religious affiliation in Estonia is very low. In the 2021 census, 71% of residents reported no religious affiliation or declined to answer. About 16%, mostly ethnic Slavs, identified with Orthodoxy, down from 24% in 2011. Another 8% identified as Lutheran, primarily among ethnic Estonians, a decline from 14% in 2000. Of the remaining 5%, most affiliated with non-Christian religions including Islam and Buddhism.

Estonia’s fertility rate rests at an extremely low 1.3 as of 2025. Although improved life spans and recently favorable immigration have lifted numbers recently, Estonia faces a declining labor force in the near future. Urbanization is also depopulating many smaller towns. Meanwhile, Tallinn’s metropolitan area now houses about a third of the population. On a brighter note, Estonia is also home to one of the world’s best-educated populations, with more than 43% of adults holding a higher education degree.

Lastly, Estonia is surrounded by larger countries in what has historically been a geopolitical flashpoint. Maintaining strong alliances through NATO and EU membership has been indispensable to both its security and economic development. Despite its small size, Estonia plays an outsized role in European politics and business.

Estonia’s Early Pre-History to its Medieval Period

The Ice Age receded in the Baltic region between 10,000 and 8,000 BCE, and the first archeological evidence of human settlement dates to around 7,500 BCE. Most scholars suggest that the ancestors of the Estonians migrated from the Ural Mountains at that time, although recent DNA research suggests that Uralic languages originated in northeastern Siberia, near Yakutia. Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian are all Uralic languages.

Early Estonians lived in agricultural and herding communities, supplementing their diets with hunting and gathering. Because the region lacked easily accessible metal deposits, Estonia’s iron age was delayed. Most tools were wood, stone, and/or bone which slowed agricultural development and left a sparse archaeological record. The Baltic region was also among the last in Europe to adopt writing, so much of what we know about its early history comes from the literate Swedish and Germanic people with whom the Estonians traded and fought. These neighbors referred to the area as Eistland (“East Lands”), an exonym that evolved into “Estonia” and was later adopted by Estonians themselves. Before this, Estonians commonly used Maarahvas, meaning “land people” or simply “locals,” as their self-designation.

- Ancient trade routes of Europe including the “Amber Road.”

- A (not wholly accurate) map from 1539 showing Livonia, Esthia, and Rivalia (an early name for Tallinn). Click here to view the original.

Early foreign accounts describe Estonia as a source of timber, furs, and honey, which were traded for goods from Byzantium and Rome. Germanic and Swedish tribes acted as middlemen along this “Amber Road,” a lucrative trade route connecting the Baltics and Scandinavia with the empires, which particularly desired the copious amber found in Latvia, Lithuania, and, to a much lesser extent, Estonia. Iron implements were slowly imported but, after about 600 AD, Estonia began extracting bog iron from its lakes and marshes and became an iron exporter. Bog iron is not profitable in the modern age and Estonia has no active iron mines.

The Estonian tribes were warriors who controlled local trade routes and occasionally raided them. By the 11th century, Estonia’s trade position strengthened as it developed ties with the rising Novgorod Republic. Throughout this era, Estonia lacked centralized political administration and existed as a number of autonomous, confederated tribes that alternately cooperated and competed for resources and power. By the 13th century, these were split roughly into Western, Northern, and Southern cultural spheres whose influence can still be seen in modern Estonian regionalism.

The Baltic Germans Conquer and Rule: The Medieval Period

Between 1208 and 1227, much of the region was conquered after Pope Celestine III called for a Baltic Crusade in 1193. The Teutonic Order, German knights originally organized to protect Western pilgrims in Jerusalem, answered the call to forcibly christianize Europe’s last pagan bastion. Many of the knights were also motivated by prospects of personal profit in conquering land and valuable trade routes. They called the papal state they created “Livonia,” after an a indigenous Finnic people living on the Baltic coast around the Daugava River’s mouth.

The creation of the papal state was led by Albert von Buxhoevden of Bremen, whom the Pope ordained Bishop of Livonia, and who, with Papal approval, established the Livonian Brotherhood as a permanent military force. Livonia, however, never became a unified polity. Its bishoprics and the Brotherhood ruled rival territories prone to frequent and sometimes violent disputes over land and power. Furthermore, although subjugation was declared complete in 1227, conflicts with local tribes continued, either as tribal uprisings or the tribes attacking in coordination with German forces. The many castles that still dot Estonia were built by Germans seeking to protect themselves mostly from other Germans and the local Estonians. Efforts at proselytization were also lackluster, a legacy still visible today in Estonia’s low levels of religious affiliation.

Northern Estonia was conquered separately by Danish crusaders who arrived in 1219, also with Papal blessing. They won a decisive victory at Lindanisse, a long-standing Estonian trading village and fortified stronghold, which they razed to build their own castle. The location became known in Estonian as Tallinn, literally “Danish Castle.” However, after political chaos followed the death of the Danish king in 1332 and a major rebellion by Estonians in 1343, the Danes could not profitably hold the land and sold their Duchy of Estonia to the Livonian Brotherhood in 1346. The administrative dividing line between north and south Estonia would remain in place until the 20th century.

The socio-economic systems established in this era favored German nobles, merchants, and urban administrators. Estonians lacked the political centralization, military technology, and manpower to resist this colonization. These Baltic Germans, as they became known as they developed their own culture and identity, became an ethnically-defined ruling force. The Estonians, likewise, were an ethnically-defined labor force. Over time, Baltic Germans consolidated control, stripping Estonians of rights to property and movement and reducing them to hereditary serfdom. Cities grew along key land and sea trade routes and were populated largely by German merchants and artisans. This ethnically-based social and economic order endured for centuries under successive empires.

All of Estonia’s major towns joined the Hanseatic League, a powerful commercial and defensive alliance of merchant guilds and market towns in Northern Europe. The League dominated Baltic Sea trade from the 13th to 17th centuries. Estonia exported furs, honey, leather, rye, barley, and oats, and imported textiles, salt, herring, and metals from other League cities. Estonia remained a major trade connection for Novgorod as well as Mucovy during this time.

Hermann Castle (pictured left) in Narva, Estonia was first built by Danish forces in 1256. It now sits directly across from the larger Ivangorod Fortress, first built in 1492, on the opposite side of the Russian-Estonian border.

The Fall of Livonia and Swedish Rule

In 1410, in response to frequent raiding parties by Teutonic Knights into Lithuanian territory, Poland and Lithuania assembled a massive army and crushed the Knights in the Battle of Guenwald. The defeat and subsequent repatriations left the knights devastated militarily and economically. This was the start of the fall of the Livonian state.

Despite further papal attempts to unify Livonia, the region remained riddled with infighting. In 1558, the Livonian War began with Poland-Lithuania, Sweden, and Muscovy all seeking to take control of the Baltic trade from the weakened state. Livonia’s traditional allies in Western Europe were unable to intervene, preoccupied with the upheavals of the Reformation. By 1561, the southern parts of Estonia had fallen under Polish rule and the Livonian Order collapsed. Fighting continued for decades, however, sparking famine and displacement for Estonians.

Sweden’s Baltic territories, as eventually ceded to Russia. Modern borders of Estonia and Latvia are superimposed for reference. Click for original.

Stability returned only in 1629 with the Treaty of Altmark, which established Swedish rule north of the Daugava River (in present-day Latvia) and Polish-Lithuanian control over lands to the south. Russia made no lasting gains. Baltic Germans continued to dominate administrative and mercantile positions. Despite some Swedish reforms, Estonian peasants remained largely unprotected under the law, allowing German landlords to consolidate power and impose increasingly heavy feudal obligations. Estonia continued to be ruled as the Duchy of Estonia (in the north) and Swedish Livonia (in the south).

The era of Swedish rule (1561–1710) is often idealized in modern Estonian histories, but this largely reflects the nobles’ experience, especially in contrast to later Russian rule, which favored no one. The greatest tragedy of the Swedish era was the Great Hunger of 1695–97, a famine that devastated much of northern Europe and was intensified in Estonia by Swedish policies that diverted grain supplies to aid starving populations in Finland and Sweden at the expense of starving Estonians. An estimated 20% of Estonia’s population died.

Swedish rule left several lasting legacies, including the establishment of printing presses in Tallinn and Tartu, the creation of an extensive public education system, and the founding of Estonia’s first university, the University of Tartu. Although schools primarily served German, Swedish, and Finnish families, Swedish parish schools promoted biblical literacy among Estonians. These efforts laid strong educational foundations and, by the eighteenth century, some records suggest that as much as half of the Estonian peasantry was literate.

Rule under the Russian Empire and the Estonian National Awakening

In 1700, during the Great Northern War, Russia again attempted to seize Estonia and its ports. Initially deflected by Sweden, Russia would overtake all its Baltic holdings by 1721, ruling both the renamed Governorate of Estonia and the Governorate of Livonia.

While Baltic Germans continued to dominate local power, by the mid-18th century, Enlightenment ideas from Germany began shaping Baltic German thought, giving rise to the Estophile Enlightenment around 1750. Estophiles emphasized human rights, and sought to improve the economic and political conditions of Estonians. Pre-German traditions such as Jaanipäev, the ruckus midsummer celebration, once disparaged for their pagan roots, were championed by Estophiles. Figures such as Johann Gottfried Herder collected and published Estonian folk songs, helping inspire a broader movement to record folklore and study the Estonian language. This contributed to the emergence of early Estonian literature.

University of Tartu, as seen in a lithograph created in 1845. Founded under Swedish rule, it would become a major hub of the Estonian National Awakening.

With the lobbying of Estophiles and similar groups in Livonia, Tsar Alexander I agreed to abolish serfdom in the Estonian and Livonian Governorates in 1816. The rest of the Russian empire would have to wait until 1861, under Alexander II, for the same reform. This began a tradition of the Russian government using the small Baltic states as pilot locations for social engineering programs, a practice that carried on even under the USSR.

With serfdom’s onerous work requirements and mobility restrictions lifted, widespread education finally became possible for Estonians, who leapt to enroll their children in schools and universities. By 1850, roughly 90% of the population older than ten was literate.

The industrial revolution accelerated social change. Europe’s then-largest cotton textile factory opened in Narva in 1857. Tallinn developed into a major port and machinery producer. Tallinn and Narva were connected in 1870 by rail to St. Petersburg, further boosting trade and mobility. Between 1860 and 1900, Estonia’s urban population tripled, and Estonians, for the first time, became the majority in major cities. Estonians had increasing opportunities to become property owners, merchants, tradesmen, journalists, and officials.

Estonian-led cultural and scholarly organizations proliferated as did Estonian-produced publications. Johann Voldemar Jannsen, the “father of Estonian journalism,” published the first Estonian-founded paper in 1857. Originally titled Perno Postimees ehk Näddalaleht (Perno Postimees or A Weekly Newspaper), it changed its name to just Postimees when it began to appear daily. It is still in publication today. In 1853, the Estonian poet Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald completed Kalevipoeg, a national epic based on collected folklore. Though heavily edited to pass tsarist censorship before its serialized publication between 1857 and 1861, it became a foundational work of Estonian literature.

The first all-Estonian Song Festival was held in Tartu in 1869. Traditional songs, carrying history and culture in short, ritualistic stanzas, had long been a central part of Estonian culture (and wider Baltic cultures). The festival has been almost continuously held every five years since and mass singing events have been regularly used in both national celebrations and protests.

Kreenholm Manufacturing Company, founded in Narva, was then Europe’s largest textile plant. Industrialization drove rapid urbanization. Andrei Simonov CC BY-SA 3.0

With Estonians now championing their own culture, the era shifted from Estiphile Enlightenment to the Estonian National Awakening around 1850. Estonians increasingly saw themselves as a united people and, most importantly, as a culture and people equal to any other. Around this time, Estonians adopted the exonym Eesti, or “Estonian” as their preferred endonym.

Estonians also increasingly received positions in government administration. Russia, wary of Germany’s unification in 1871, initiated Russification policies to reduce German influence over the Baltic Germans. Intensified under Alexander III in the 1880s, these policies led many German speakers to be replaced with Estonians who had learned Russian. Thus, by the turn of the century, Estonians had demonstrated their ability to thrive in all sectors of society, which only encouraged their growing desire for national self-determination.

The Early 20th Century and the First Estonian Republic

By the 1905 Revolution, calls for land redistribution, better working conditions, and greater autonomy had found support with many rural and urban Estonians. Large protests were held in Estonia’s major cities, and some 40,000 Estonians protested in St. Petersburg for autonomy. An Estonian congress met in Tallinn in late November to prepare the ground for a sovereignty within the Russian empire. December brought rural riots that left hundreds of manors burnt and several landowners dead. Roughly 300 people died in political violence in 1905. After Russia reasserted control, hundreds of Estonians were executed for their roles in the revolution. While few gains were made, the events sharply raised public political consciousness.

World War I deepened discontent. About 100,000 Estonian men, some 10% of the population, were mobilized. Of these, 10% never returned. Estonians endured severe wartime shortages and both Estonians and Germans saw social freedoms restricted. The tsarist authorities, distrusting all Germans, closed German schools and banned the use of German in public.

After the 1917 Revolution toppled the tsar, Estonia asserted autonomy, held elections, and formed military units that drew enthusiastic support. The Bolsheviks invaded, reasserting Russian control, but were forced to cancel new elections when two-thirds of voters backed independence. With WWI still ongoing, Germany invaded the Baltics and the Soviets retreated. Estonia issued its 1918 Declaration of Independence in the interim.

- Estonian Soldiers Crossing the Daugava, a 1936 painting by Oskar Sädek, an Estonian painter famed for his works depicting the Estonian War of Independence.

- Memorial to the Battle of Paju in Estonia, the site of one the major battles of the Estonian War of Independence.

- The building where the Treaty of Tartu was signed is now a school. It bears a plaque outside explaining its history. Photo by the author, Mari Paine.

Attempts to incorporate the Baltics halted when, in 1918, the imperial German government collapsed and the new republic recognized the Estonian Provisional Government and withdrew. Less than two weeks later, the Soviets invaded, starting the Estonian War of Independence.

With aid from Britain and other allies, Estonia reassembled its army and drove out Bolshevik troops from Estonia, and then assisted in driving them from Livonia as well. Free elections were held in 1919, and in early 1920 the Soviets signed the Tartu Peace Treaty, recognizing Estonia’s independence, ceding Estonia new lands, and renouncing all territorial claims to Estonia.

In 1920, a British-moderated agreement between Tallinn and Riga split the former Governorate of Livonia, creating what is now roughly the modern state of Latvia and uniting the northern and southern halves of modern Estonia into one sovereign republic.

Rise and Fall of the Estonian Republic and World War II

Rebuilding Estonia in the 1920s began with the politically and economically successful Land Act, which nationalized and redistributed the massive Baltic German estates as 35,000 small Estonian-owned farms. Most reforms held to free market principles. Oil shale, first test-mined in 1916, was developed via a state-controlled joint stock company that established two processing plants within the decade. Most major industries, including textiles, forestry, and machinebuilding remained privately owned but with greater regulations, especially for labor. They were retooled to focus on domestic consumption and export to Europe.

Despite early successes, Estonia was hit hard by the global Great Depression in 1929. Collapsing export markets caused factory and farm outputs to fall by 20% to 45%. Economic pressures worsened Estonia’s already unstable democracy, marked by short-lived coalition governments that had averaged about 11 months since 1920.

In 1934, Prime Minister Konstantin Päts seized power in a coup to prevent the far-right Vaps Movement from taking control. In an effort to stabilize the economy, temper political polarization, and counter growing threats from Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s USSR, Päts resorted to martial law, censorship, and restrictions on opposition.

Above: Color footage showing a prosperous Estonia in the 1930s.

By the late 1930s, Päts’ protections for domestic industry and incentives for focusing on domestic inputs and markets helped achieve a swift economic recovery. However, this would not save the Estonian Republic. Following the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Germany and the USSR moved to assert their dominance. Germany compelled Estonia to sign an agreement for the “voluntary” resettlement of around 13,000 Baltic Germans, mostly to occupied Poland. This ended the Baltic German community’s centuries-long presence in the region. At the same time, the Soviet Union demanded that Estonia accept Soviet troops or face invasion. Although Estonia agreed to host them, Moscow used this military presence to install a puppet government, which then “requested” accession to the USSR in 1940.

Soviet rule brought censorship, arrests, and mass repression. To quash resistance, ten thousand Estonians were deported on June 14, 1941. Men, including Konstantin Päts, were sent to labor camps where most died, while women and children were exiled to Siberia.

Germany’s WWII invasion of the USSR occurred just days later and reached Estonia in early July. Initially welcomed by some as liberators from Soviet terror, the Nazis in fact planned to depopulate the Baltics by at least 50% to make way for German settlers. All of Estonia’s 4000 Jews fled or were murdered and roughly 6,000 Estonians, mostly accused of communist ties, were executed. About 50,000 Estonians ended up as labor in Germany, some as early paid recruits and later as forced deportees to labor camps. Thousands fled as Estonia became a frontline between the Red Army, the Wehrmacht, and the Forest Brothers, a guerrilla group fighting for an independent Estonia. By the end of World War II, Estonia had lost nearly a quarter of its population.

Soviet Estonia

After WWII, the USSR reincorporated Estonia, in the process returning to Russia territory that Estonia had gained in the Treaty of Tartu. Estonia is still pushing for the return of this land today.

Although WWII was officially over, the Forest Brothers kept fighting for independence. In response, the Soviets deported about 21,000 Estonians to Siberia in 1949. Meant to support collectivization, the deportations also targeted the Forest Brothers’ support network. Although weakened, the Forest Brothers survived for decades, with the last capture recorded in 1978 and others dying later of old age still in hiding.

- A band of Forest Brothers pictured with their families celebrating a Soviet retreat in 1941.

- A group of Forest Brothers pictured in 1946, still in active fighting against the Soviets after WWII ended.

- Monument to August Sabbe, the last known Forest Brother located by the Soviet KGB. It marks the place where he killed himself rather than be apprehended. Laanõ Valdis CC BY-SA 3.0

Because Estonia was rebellious and at the USSR’s sensitive western border, the Soviets heavily militarized it. Up to 100,000 servicemen were based across Tallinn’s massive Baltic naval port, Tartu’s Raadi Airfield (the largest Soviet base in the Baltics), and other facilities like Sillamäe’s secret uranium processing plant and Paldiski’s nuclear submarine training center. Some 3500 KGB agents kept tiny Estonia under strict surveillance, and travel, especially for foreigners, was tightly controlled.

Estonia’s economy, including established shale oil, dairy, pork, construction material, textile, and paper industries, was developed to serve the Soviet republics. To supply labor to depopulated Estonia, 300,000–400,000 Russians were resettled, driving the Estonian share of the population down to about 65% by 1979. Russian became common in urban areas and dominant in military settlements. Most of the resettled Russians could be counted on to support Communist rule.

Fearing backlash, Soviet leadership did not ban Estonia’s beloved song festivals and instead tried to co-opt them. Estonian songs were approved if deemed politically neutral and Soviet flags and songs were required additions. However, in 1965, the choir “forgot” not to sing the unapproved “My Fatherland is My Love.” Specifically banned for the 1969 festival, the crowd added it “spontaneously.” Despite orders to stop and a military band dispatched to drown them out, an estimated 100,000-plus audience members joined in the unstoppable singing.

Later protests became more political. Students successfully resisted Russification policies with walkouts in 1980. In 1987, environmentalists halted a toxic phosphorite mining project and other protesters demanded publication of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The People’s Front, formed in 1988, officially to support perestroika, quickly became the center of the independence movement, organizing huge nonviolent demonstrations, often centered around song festivals. Their most iconic action, coordinated with similar groups across the Baltics, was the 1989 Baltic Way, a 410-mile human chain from Tallinn to Vilnius involving two million participants peacefully demanding autonomy and democratic rights. Known for their use of song and culture, Estonia’s protests eventually became known as the “Singing Revolution.”

- The Estonian National Song Festival, 1896.

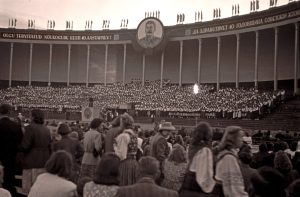

- The Estonian National Song Festival, 1950. Note the image of Stalin and the inscription “Celebrating 40 Years of the Estonian SSSR” displayed.

- The Estonian National Song Festival, 2025. Note that, dispite the heavy rain visible in the photo, tens of thousands still attended. Photo by the author, Mari Paine.

Despite counterprotests by Estonian communists and many ethnic Russians, by late 1988 even Estonia’s communist leaders shifted toward national interests. They restored the former republic’s flag to national status, declared Estonian the state language, and asserted the supremacy of Estonian laws over Moscow’s. Finally, in a 1991 referendum, nearly 80% of the public voted for independence. Estonia’s Supreme Soviet declared the restoration of the independent state and Moscow recognized Baltic independence a few weeks later.

The Estonian diaspora, spread throughout the West and operating a government-in-exile from New York, had actively lobbied their adopted homes to never recognize Soviet annexation and even maintain pre-war Estonian diplomatic missions. Thus, when Estonia re-entered the international community in 1991, it did so not as a new state but as a restored republic.

Modern Estonia

In 1991, Estonia again set out to rebuild itself. Elections in 1992 ushered in a new constitution and government. The most controversial step was limiting citizenship as well as voting rights to those that could prove that they or their ancestors had been citizens of the original Estonian republic. This disenfranchised many Soviet-era settlers and others lacking documentation. The 1993 Aliens Act formalized these rules, leaving roughly one-third of residents, mostly Russian speakers, with “alien passports.” Many later naturalized, a process that involved showing the ability to speak Estonian. Others emigrated. About 5% of the population remains stateless.

The new government, elected with a strong mandate for radical reform, implemented one of the fastest and most comprehensive post-Soviet transitions to a free-market system. Estonia stabilized its currency by pegging it to the Deutsche Mark, adopted strict fiscal discipline, a flat tax, and privatized the vast majority of state enterprises within four years. Sales focused on “real owners” who proposed the strongest business plans, rather than those simply making the highest bids. Agricultural and land reform proceeded more slowly due to an initial focus on returning the land to pre-collectivization owners. E-governance was adopted early as a cost-saving measure and the infrastructure built to power it soon spurred a digital boom that helped launch companies such as Skype, Wise, and Bolt in Estonia.

Judicial and police reforms accompanied economic reforms. Soviet institutions were dissolved, new legal foundations were created, and judges, lawyers, and police were required to recertify under new standards. These reforms produced rapid growth, high economic freedom, and rising living standards and human development along with low corruption and high press freedom.

Estonia’s parliamentary governmental system involves multiple small parties; all governments are coalition-based. Though these coalitions often shift, most parties share commitments to fiscal conservatism and national interests, maintaining broad policy continuity.

Above: A CNBC report explaining Estonia’s digital government services.

Every Estonian male must complete six months of military training and post-1991 security policy has emphasized integration with Western institutions. Estonia joined the EU and NATO in 2004, the Schengen Area in 2007, and the Eurozone in 2011. NATO bases are located in Tapa and Ämari. Estonia plays active regional roles through the Nordic Battlegroup, Baltic Defence College, and Baltic Battalion. Meanwhile, the Baltic Council of Ministers and the Baltic Economic Association help coordinate high level government policies and Central Bank actions.

In 2007, a Soviet war memorial was moved from downtown Tallinn to a graveyard in the city outskirts. This sparked two nights of riots by local Russians and was followed by cyberattacks, thought to have come from Russia, on Estonian state and financial institutions.

2008 brought a major contraction to the strong growth that had earned the Baltic countries the nickname “Baltic Tigers.” Much of this growth had been driven by debt-financed investment rather than productivity gains. Although the resulting bubble burst painfully, Estonia maintained fiscal discipline, avoided currency depreciation and bailouts, and recovered within two years. Other than a 3% contraction during Covid in 2020, Estonia returned to growth until 2022.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused new economic shocks. EU energy prices spiked, driving record inflation. Estonia’s central bank raised interest rates to counter inflation, which further slowed an economy already affected by higher input costs, falling exports, and declining real wages. Estonia has also begun major defense infrastructure investments along its Russian border and plans to raise defense spending from roughly 2% of GDP to 5.6% by 2029.

Searching for a new economic growth engine, recent regional policy reforms include pilot Regional Development Agreements, designed to coordinate national and local priorities through “place-based” planning supported by EU funds.

Entering 2025, key issues for Estonian voters include inflation, the cost of living, labor shortages, maintaining the social safety net, and national security.

Conclusion

Estonia today navigates challenges and advantages shaped by its multilingual society, small, open economic market, and security environment. A key cultural issue remains the integration of its sizable Russian-speaking population, which intersects with policies on language education, citizenship, and media consumption. At the convergence of major sea routes, Estonia remains a cornerstone of European security, a role bolstered by the country’s strengths as a digital innovator and cybersecurity hub. Low birth rates have created long-term concerns for labor markets, rural vitality, and the sustainability of social programs. However, solid economic policies have allowed Estonia to recover from crises quickly and provide for a high quality of life. Regionally, Russia’s war in Ukraine has heightened security priorities, deepened defense investments, and encouraged active coordination with NATO.

Estonia seeks to preserve its national identity and sovereignty with strong alliances, innovative policies and technologies, promotion of its language and culture, and regulated inclusivity.

You’ll Also Love

Turkmenistan: A Rich, Desert Land

Turkmenistan consists mostly of sparsely-inhabited desert, but has still found itself contested between civilizations throughout history. Over the past century, it has been particularly associated…

Kiev: At the Center of a Divided Country

The ancient city of Kiev continues to thrive as the most populous city of Ukraine. Much like other post-Soviet capitals, Kiev’s future looks bright, despite…

Latvia: A Case Study of Colonization and Independence

Latvia is a small country on the Baltic Sea coast. Although it has maintained a distinct language and culture for hundreds of years, it has…

Moscow: Modern and historic challenges

Moscow’s official population of 10.5 million makes it the world’s seventh most populous city. In addition, the city also contains nearly two million official “guests,”…

Ukraine: Between Russia and Europe

Ukraine is no longer “The Ukraine.” For centuries, the definite article was considered appropriate, given the land’s history and the name’s meaning. However, given recent…