“Prosperity in Unity” is the official motto of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, a parliamentary republic that exists within Ukraine and occupies most of the Crimean Peninsula, with the exclusion of the strategic city of Sevastopol. Yet the history of Crimea—both the republic and the peninsula itself—has been far more defined by conflict and separatism than prosperity and unity.

Today, Crimea is perhaps best known for the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the resort town of Yalta, where Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill famously met to decide the fate of post-WWII Europe. Perhaps more important to understanding modern Crimea, however, are the questions of Crimean identity and independence that have ignited international tensions and overshadowed the area for the last three decades. Though Crimea remains a popular and scenic tourist destination, it is also a potential flashpoint for Ukrainian-Russian relations and even for Ukrainian territorial integrity.

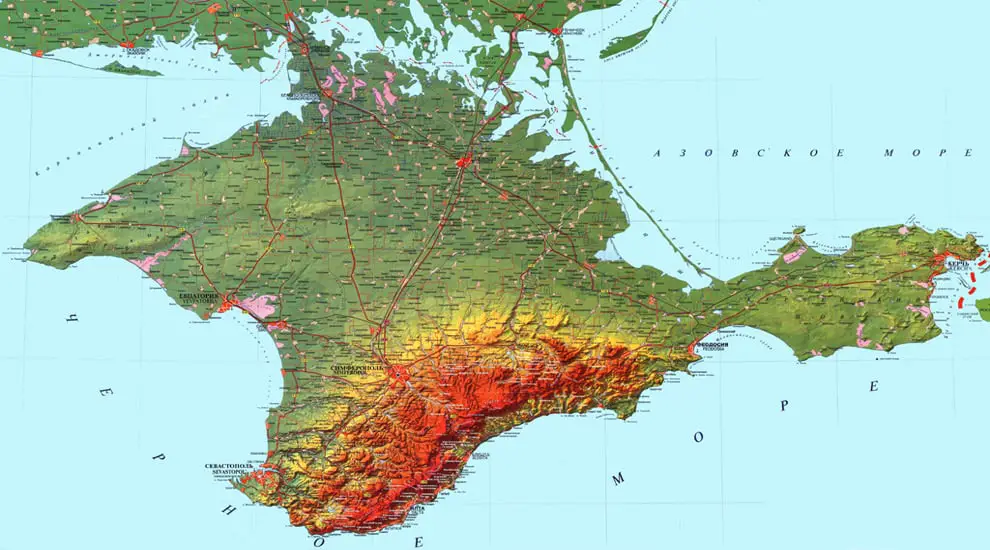

Topographical map of Crimea and its immediate area, showing the massive Crimean Mountains.

Geography and Demographics of Crimea

The southeastern flank of the peninsula is bordered by mountains, creating a naturally defensible front whose rocky shores also feature a number of natural ports. From this southern flank, access to the Sea of Azov – through the Strait of Kerch and which provides access to the strategic Don River and still more of the Black Earth region – can be partially controlled. Today, this mountainous region is dotted with vineyards, orchards, fisheries, and beautiful resort towns such as Yalta.

The southwestern flank features a large natural indenture that helps create calm sailing waters and which features two large ports: one at the north at Yevpatoria and the other, larger and supported by several large natural bays, at Sevastopol in the south. Russia now maintains a large naval base at Sevastopol on land that it rents, controversially, from Ukraine.

At the north, Crimea connects to the mainland via a narrow ten-mile wide strip of land. Most of the peninsula, however, which is about the size of Massachusetts and home to nearly two million people, is given over to flat, semiarid plains that are well-watered by the rivers flowing from the southern mountains. Today, these plains are a heavy patchwork of farms producing cereals, vegetables, poultry, mutton, cattle, and more. About sixty percent of the region’s GDP currently comes from agriculture and food production. Crimea also has natural sources of salt and limestone, basic goods that humans have coveted since ancient times. Thus, not only is the peninsula a strategic point from which the commercially and militarily valuable Black Sea can be controlled, but it is also itself able to support the populations and military forces needed to maintain control over the position.

Crimea’s long history of war and colonization is reflected in its current ethnic composition, which is now mostly Russian (58%), Ukrainians (26%), and Crimean Tatars (12%). While Ukrainians and Russians share many elements of their Slavic language, culture, religion, and history, the Tatars are an ethnic Turkic people who speak Turkic and are mostly Sunni Muslim. The Russian and Ukrainian sub-populations are currently shrinking, as members seek greater economic opportunity elsewhere, and the ethnic Crimean Tatar population is growing as populations formerly exiled continue to return to their homeland and have higher than average birthrates.

Since independence came in 1991, the status of Crimea has been under question: whether it should remain part of Ukraine, be independent, or become part of Russia. Polling numbers have fluctuated widely over the years, but the current trend seems to be favoring stability and remaining part of Ukraine. According to one poll, the number of Crimeans claiming Ukraine as their motherland has risen to over 71% in 2011 from just 38% in 2008. However, efforts to expand the usage of the Ukrainian language have been less than successful. Russian is the official language of government and business and the primary language of 77% of the population and Crimean Tatar remains a proud element of local Tatar culture. Religiously, Crimea is a mixture of Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, and Sunni Muslim beliefs, with the minarets of mosques rising next to church steeples along the coast of the Black Sea.

Early History and the Rise of the Crimean Tatars

While a range of peoples likely inhabited the Crimean Peninsula in ancient times, the two major civilizations there were the Scythians and Tauri. The Scythians were a people known as both fierce warriors and incredible goldsmiths who populated the plains areas. When the ancient Greeks began founding colonies in the Black Sea by the fifth century BC, they avoided the mountainous southern regions, which were populated by the Tauri and who were famous as a people who excelled in war, plunder, and human sacrifice.

The ancient Greeks called the entire peninsula “Tauris” or “Taurica” after these people. Greek mythology features stories set here such one describing Hercules plow the entire region using a giant ox (“Taurus” in Greek). Greek settlements were built primarily along the coasts, notably at Theodosia (now Feodosiya) and Chersonesos (modern-day Sevastopol), before being absorbed into the expanding Roman Empire. Located at the far reaches of the empire, the land was not heavily influenced by Roman rule and was largely used as a military and diplomatic outpost. As Rome collapsed, however, Crimea underwent centuries of invasion from first the Goths (AD 250), the Huns (376), the Bulgars (4th–8th century), the Khazars (8th century), Kievan Rus’ (10th–11th centuries), the Byzantine Empire (1016), the Kipchaks (1050), and the Mongols (1237). This brought a wide range of influences including Germanic, Turkic, Slavic, and Asiatic.

Major Greek colonies in Crimea, ca. 500 BC.

The various Turkic peoples, mixing with others, eventually coalesced into a people known as the Crimean Tatars who then emerged as a nation under Mongol rule. The Mongols founded a new capital for the peninsula at a city called Qirim, which means “my hill” in Crimean Tatar. This city, now known as “Old Krym” still stands at the far eastern end of the southern mountain range, near the port of Feodosiya. As the Golden Horde was collapsing, the Crimean Tatars fought and eventually defeated the Mongols in a bid for their independence in the early 15th Century. The new state was called Qirim Hanligi in the local Turkic language, was majority-Muslim, and eventually controlled most of the peninsula and large swaths of the fertile steppes to the north. Today’s name of “Crimea” comes from a linguistic corruption of the Turkic word “Qirim.”

Before it could stabilize its internal politics, The Crimean Khanate was invaded by the Ottomans and proclaimed a protectorate. By the 16th century, however, it became clear that Crimea was more an ally than a subject of the Ottomans and exercised considerable autonomy within the empire. The Khanate grew wealtheir and more powerful, in part, by running slaving missions into Eastern Europe and selling Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Lithuanians and others to slavers in the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.

The Crimean Khanate, ca. 1600 AD. For a fascinating podcast about the Khanate and its unique place within the Ottoman Empire, click here.

By the middle of the 16th Century, the Khanate felt powerful enough to declare itself the successor of the Golden Horde. It then attempted to incorporate all other Tatar peoples, which would have pushed its borders deep into Siberia. This placed the Khanate in direct opposition to Russia’s expansionary ambitions and in a resulting war, the Khanate managed to reach and burn Moscow. However, the Russians, with the aid of its Cossack forces, eventually proved the stronger. With The Ottoman Empire, the Khanate’s main ally, in decline, the Russians invaded the peninsula in 1735-1739, waging scorched-earth campaigns to subdue their rivals. Crimea was eventually annexed by Russia in 1783 and the Khanate was destroyed by the turn of the century.

In the post-war years, many Crimean Tatars were arrested, killed, or deported and many more fled to the Ottoman Empire. The Russians quickly launched a major building program, building not only palatial homes, expanding and rebuilding cities, but also established Sevastopol as a strategically important port for the imperial fleet. The Russian takeover of Crimea destroyed the buffer area that had previously existed between Russia and Turkey and upset the already tenuous balance of power in the Black Sea.

The Crimean War: Crimea in Global Geopolitics

The Tsar’s Black Sea Fleet was seen as an unacceptable threat to Western European economic and military interests and the balance of power in the Mediterranean, which Britain and France sought to maintain. Much of the Russian fleet was blockaded in Sevastopol and destroyed. On land, repeated Russian attempts to break the allied lines proved unsuccessful and, after yearlong siege and a series of bloody battles, Sevastopol fell in September, 1855. The war ended in 1856 after continued defeats for Russian forces and growing political discontent in Britain brought both sides to the peace table.

The Crimean War was marked by logistical and tactical blunders on both sides, as well as key technological innovations that changed the dynamics of warfare. It was the Crimean War that saw the first military use of railways, telegraphs, the minie ball, trenches, and modern nursing (thanks to Florence Nightingale). It was also the first major conflict to be extensively covered by frontline journalists, and it was the London newspaper accounts of the Battle of Balaklava, fought in the effort to take Sevastopol, that led Sir Alfred Lord Tennyson to pen his famous poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” English newspaper accounts also helped fuel popular discontent about the war, helping to fan the discontent that would eventually help end the war with The Treaty of Paris.

From Yalta to Yeltsin: The Soviet and Post-Soviet Transitions

The Treaty of Paris forced Russia to abandon any naval presence on the Black Sea coast, greatly weakening Russian influence in the region. However, following the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, Russia renounced the treaty and reasserted its authority in Crimea and the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a heyday for Crimea as a retreat for the Russian elite. This included the political elite, artists, and writers such as Tolstoy, many of whom had served as officers on the peninsula during the war.

After the 1917 Revolution, the area became a stronghold of the anti-Bolshevik White Russian army, who were eventually defeated in 1920 by the advancing Red Army. The following year the Crimean Tatars, sensing another opportunity for freedom, briefly established an independent Crimean state, but were quickly absorbed by the new Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which in turn became a part of the Soviet Union. While Lenin initially attempted to appease the Crimean Tatars, allowing them to retain their cultural heritage, Stalin initiated a much more aggressive policy of forced integration.

Josef Stalin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill met in February, 1945 to reorganize Europe for the post-war era.

Following two severe famines in the 1920s and 1930s, the peninsula was the site of heavy fighting during World War II as German forces invaded the territory during their drive east. Fierce battles at the Isthmus of Perekop and the Siege of Sevastopol again devastated Crimea, most of which fell to the Nazis. The Soviets liberated it in late 1944, in advance of the famous Allied conference at Yalta, one of the most monumental meetings of the 20th century. The small Crimean resort town hosted Josef Stalin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill, who met in February, 1945 to reorganize Europe for the post-war era.

Crimea experienced its own postwar reorganization, as the Soviet leadership deported the entire ethnic Tatar population to Central Asia on charges of collaboration with the Germans. The Armenian, Bulgarian, and Greek populations were also deported in advance of Crimea’s integration into the reorganized USSR as a separate oblast, or province. In 1954, Crimea was transferred to the jurisdiction of the newly-organized Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic—a move that laid the foundation for the modern conflict over Crimean sovereignty and identity.

Soviet rule brought a revival of Crimea’s tourism industries along with major development of infrastructure and heavy industry, particularly in the ports of Kerch and Sevastopol as well as in Simferopol, the landlocked capital. Much of this infrastructure, which focused on chemical and mechanical engineering, metal working, and fuel production, is still in place today, although much of it is now outdated or failing.

The peninsula’s continued strategic naval importance lead to Sevastopol being declared a closed city and, in Balaklava (now incorporated in Sevastopol), the Soviets built a massive secret submarine base. “Facility 825,” as it was known, was able to safely shelter 10,000 people and an entire division of submarines from nuclear attack for up to three years. Today, it is a popular museum open to tourists.

In the summer of 1991, then-President Mikhail Gorbachev was vacationing in Crimea when he was placed under house arrest during the August Coup. While the coup was eventually put down, Gorbachev had been destroyed politically by its end and the Soviet Union would collapse before the end of the year.

After 1991 and Ukrainian independence, however, Crimea remained a staunchly pro-Russian region. In the 1991 referendum held across the USSR, 88% of its citizens voted in favor of preserving the Soviet Union—the highest percentage in all of Ukraine. Many in Crimea resented the USSR’s eventual top-down destruction by its leaders. Social tensions also rose when many Tatars, returning from exile and frustrated in their failed attempts to reclaim the land taken from them when their ancestors were exiled.

All this helped push a movement that led to the Republic of Crimea proclaiming self-government in May 1992. Ambitions of total independence were quickly scaled down, and Crimea agreed to remain part of Ukraine, albeit as an autonomous republic. This apparently peaceful resolution was only a prelude to a chaotic new chapter of Crimean politics, however, as various factions competed for power in the early 1990s.

“The Sevastopol Problem” in the Post-Soviet Era

Many members of Yeltsin’s administration aggressively asserted that Crimea was rightfully the territory of the Russian Federation. Even today, many Russian politicians, including former Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, publically assert that the 1954 transfer of Crimea to Ukraine was illegitimate or illegal.

The key issue, of course, is that with the loss of Ukraine and Crimea, Russia lost much of its important influence over The Black Sea. Of especial significance is Sevastopol, home to the Russian Black Sea Fleet and a strategic point that gave Russia wide access to the Mediterranean.

Aggressive Russian rhetoric over Sevastopol and problems such as local corruption and ethnic competition helped fuel the rise of separatism in the early 1990s. From 1993 to 1995, the Russian Bloc movement became the most powerful political force in Crimea. Yuriy Meshkov, a separatist supported by the Bloc was elected president of the Crimean Republic in 1994. In 1993, the Russian Duma declared Sevastopol to be a “Russian federal city” under Russian control. However, internal divisions and a lack of official support from Yeltsin led to the breakdown and marginalization of the separatist movement between 1995 and 1996. Meshkov was removed from power by the Ukrainian parliament, a new constitution was pushed through, and new leadership installed.

In 1997, the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet was divided between Russia and Ukraine. Russia additionally recognized Ukraine’s legitimacy to all land in Crimea (including Sevastopol) and which gave Russia a temporary twenty-year lease on its naval facilities in Sevastopol. At the time, Yeltsin declared, “This puts an end to the so-called Sevastopol problem,” but in actuality tension persisted beneath the surface.

Crimea Today

While Crimean nationalism was not able to secure the support it sought from Yeltsin, hopes have renewed under Vladimir Putin. After the Russian invasion of Georgia and Russia’s official support of the independence declared by South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2008, anti-Ukrainian riots broke out in Crimea in 2009. Many residents hold Russian passports, as did the residents of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, a result of Russia’s policy of allowing former Soviet citizens to apply for Russian citizenship. Many rioters in Crimea had hoped for Russian intervention in the resulting conflict, although that intervention never came.

Despite Ukraine’s current constitution forbidding foreign military bases on Ukrainian soil, a new deal was recently struck to allow the Russian base in Sevastopol to remain under Russian control until 2042 in exchange for a 30% discount on natural gas imports. This was made possible thanks to much of Ukraine’s aging industrial infrastructure and domestic heating being reliant on natural gas imported from Russia. Sevastopol is now a federal city with Ukraine, with special status apart from the constitution, in order to accommodate this.

Economically, Crimea, like much of Ukraine, is suffering from underdeveloped infrastructure and outdated industries. While tourism for Crimea offers substantial possibilities, most of its economy is devoted to agriculture. Although the politics of Crimea is currently considered to be relatively stable, problems remain concerning the status of the Crimean Tatars and their claims to their ancestral land, the status of the strategic port of Sevastopol, and the status of the majority Russian population living within the Ukrainian state. Thus, while not a conflict zone like South Ossetia or Transdnestria, concerns about the political future of Crimea are well grounded.

Currently, Crimea is the same enigmatic and conflicted mixture of ethnicities and identities as it has always been. Located in a strategic position between numerous civilizations, it has long been coveted and contested. Populated by a unique mix of nationalities and with a geography separated from that of its mainland, it also hosts some aspirations of independence. Which direction it might take – toward a new era of development and prosperity, or toward new conflicts – toward independence or toward integration with Ukraine or even Russia, is a question which may always fascinate those interested in global politics.

SRAS Programs in Ukraine