As someone who works in publishing and with student authors, I have had the opportunity to both work with generative AI and with students working with generative AI. Here, I will share some insights gained from the experience into how AI is affecting publishing and education.

Using AI in Publishing

For the last 20 years, I’ve led publishing efforts as editor and a principal author for SRAS, an organization that offers study abroad programs across Eastern and Central Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. As part of a wider effort to educate people at home about these unique places and thier cultures, our Family of Sites features information covering thousands of webpages across six different sites, much of it written by students.

Maintaining these resources is no easy task. Articles should be updated from time to time – not only to reflect the most recent events and knowledge, but also to maintain search engine relevance, as search engines consider publication dates in their rankings. In addition, other elements such as formatting and presentation require occasional “facelifts” to keep the pages fresh in the eyes of readers and engines alike.

I’ve experimented with AI, mostly ChatGPT 4, with most of this. GPT 4 is an upgraded, paid version of the free online service. Generally, in terms of simple code or format updates, the system is pretty capable of being used as a more powerful version of copy and replace, so long as the directions are simple and the system is allowed to process just 1-2 at a time. In terms of writing, however, it is still impressive, but much less capable.

As a writing tool, let’s start with what AI is good at. Asking it for definitions, lists of examples, or potential talking points for a subject are all generally good uses of AI. Here, it can be more useful than Google as the questions are answered in the form of a short synopsis rather a stack of results that have to be individually filtered, read, and searched for relevant information. Any results generated by GPT will still need to be edited for brevity, context, and accuracy and the lists of examples or talking points will need to be pruned and/or supplemented. However, it does well as a very basic sounding board and generative search engine. I have found that it can send me in interesting directions that I may not have gone before – but it can also just as easily suggest inaccurate examples and directions.

Where the AI begins to break down is with generating longer text on specific subjects. We might ask the program to generate 5 paragraphs of 750 characters or less on a general subject – a very basic school essay. This is likely to result in an output that contains around 20-30% fluff. Fluff helps fill the required area with words that sound confident and are grammatically correct, but doesn’t actually tell us any provable facts or unnecessarily repeats facts already given. There are also likely to be at least 1-2 factual errors in the text that should be identified and removed or corrected. In other words, it’s likely to come back as a basic school essay written by a student who excels at grammar and spelling but has otherwise not tried very hard and probably should have done much more research.

More importantly, AI breaks down on niche subjects catastrophically. Asking it to write about, for example, the history of Russia is likely to get you a nice, if superficial and boring, text. Meanwhile, asking it to write on the effects of the Urartu Kingdom on the development of Armenian culture, is likely to get you a pile of unusable drivel. Fluff percentages and inaccuracies escalate proportionately to the specificity and “nicheness” of the subject at hand. In other words, if it is not a subject that the AI has been specifically trained on, the AI is likely to try to fill the space and complete the assignment while supplying little to no actual knowledge. The output resembles that of a mediocre student put in the same position.

The Use of AI in Student Writing

Over the last 20 years, I have worked with hundreds of student authors on various publication projects. Today, most of our student writers participate in publication through of our Online Research Internships.

I have had student authors who seemed addicted to AI and who were unable to resolve issues created by it. They continually sent in material that was obviously created and even revised by AI, even after they were told not to. While some additional prompts can improve the output, some seem to only confuse the program and the resulting output can be worse. This is especially the case when the original problem was that the original text showed a profound misunderstanding or even no real knowledge of the subject.

None of these students completed their internship nor was any of the work they submitted published. I got the impression that even their emails to me were likely AI-generated, always skirting any discussion of AI that I brought up in previous emails and instead diligently professing a desire to move forward with the process.

AI has use as an advanced writing aid and chat buddy. It can generate helpful ideas, but it cannot generate anything that can or should be handed in without the further application of human knowledge, research, and editing. Effective use of AI requires a knowledgeable writer with, in fact, advanced writing skills – the ability to see bad, boring, superfluous, inaccurate, or even nonsensical writing and to correct it.

The main danger of AI is that it writes with grammatically correct confidence and thus can appear to be a sort of magical toy that can make homework simply disappear by plugging the teacher’s writing prompt into a machine. Further, as we have seen in the section above, AI can generate approximately the equivalent of mediocre student writing, such that one might think that its use should be “good enough” for the student who does not desire to excel. There are two major problems with this. First, with the decreasing ability of the program to cope with more specific and niche subjects, it will not be powerful enough for students in higher-level courses. Second, it is certainly not powerful enough for professional-level work.

AI is a generative system that “guesses” at what the next word should be based on statistical averages. It does not produce original thought and is not concerned with the accuracy of the facts it presents. While future iterations of the technology may improve upon this, it is unlikely that it will be able to produce anything that is not fundamentally derivative and which does not require editing and fact-checking.

Working with AI and student writers are similar processes. With AI, if initial results are not what you are looking for, you might go back and alter your prompt, making it more or less specific, asking the AI to address the issue as a specific character, such as a cultural anthropologist or military historian, for instance. You might ask the AI to develop weak but interesting claims further, which can also sometimes yield interesting results. You might also ask the program to rewrite a text for greater brevity or to avoid certain “crutch words” that it tends to overuse (such as “delve” and “tapestry”).

Similarly, I typically take student writers through a three-step process. The first draft is usually sent back with broad-stroke comments pointing out arguments that need to be strengthened and ideas that should be developed. I point out sentences that could be made clearer, claims to reconsider, evidence that should be cited, etc. The second draft process, if the main issues from the first draft are resolved, is much more precise. More specific notes are made and sometimes, as I am usually working remotely with students, I will make some edits myself and leave comments on them citing the reason for the edit. This is often the clearest way to show how to make something more concise, break up long sentences, transition within an argument, etc. By the third draft, we are usually just fine-tuning and proofreading to prepare the text for final publication.

The main difference between working with AI and students is that working with students is infinitely more satisfying. Having worked with AI, you are left with essentially piles of information that might be juggled and stitched together and still heavily rewritten. The next time you work with the program, you will go through the same piecemeal process. Working with a student, you are left with a solid, publishable paper that both the editor and the author can be proud of. The next article received from the student usually requires less editing as the student learns better the expectations and the writing techniques that were taught to them. By the end of one our internship cycles, which cover 3-6 articles, it is almost always clear that the student has become more adept at writing more concise, better argued, and more informative papers. In other words, the student has learned to write professionally.

The Critical Juncture of AI’s Arrival and the Way Forward

Perhaps the most unfortunate aspect of AI is that has arrived at a time when many people perceive education and expertise as devalued commodities. Falling college application rates and especially falling enrollments in humanities and language classes are concrete signs of this. So is the increasingly apparent assumption of many people that the opinion of any one person is equal to that of any other – even in cases where one person has had no prior study and the other has dedicated years to understanding the subject at hand.

Because many believe that all voices on all matters are equal and because AI seems to speak with a human voice, this will speed its unquestioning adoption by many publishers and students. YouTube has many videos of vloggers showing how to make money by automating the creation of monetized websites. In these instances, an AI is given a subject, breaks it down into various headings, writes webpages based on those headings, and publishes them, often without editing or verification of the facts presented, directly to a new site. Monetization agencies are also encouraging using AI without human intervention to rapidly develop sites. This is obviously driven by the same philosophy as followed by my student writers who refused to not work exclusively through AI.

It is easy to see what might happen in a worst-case scenario. The Internet can be rapidly flooded by unquestioned AI-produced drivel. Because AI learns primarily from material published online, the process becomes cyclical and exponential as the flood increases and as AI learns from itself. Student writing, attempting to rely on AI as a tool if not a magical toy for doing homework, also becomes hopelessly infected. Real knowledge then becomes increasingly hard to differentiate from AI “hallucinations” because the hallucinations can be cited within so many published sources.

To ensure that the rise of AI does not disrupt the flow of human information and human education, we should not waste time by attempting to ban AI from student writing. The technology is being rapidly adopted and, like calculators and the Internet before it, will likely be unfazed by educators attempting to stop it. Instead, we need to de-mystify the tool to ensure that students know that it is not a “magical toy,” but can be a useful and legitimate tool when used properly.

I know from experience that AI can be used in non-destructive ways in publishing and I have seen students able to use AI appropriately to generate ideas, add in clear definitions of unfamiliar topics, and as an advanced grammar and spell checker. Most students are able to send in flawed drafts and still take human direction and make human edits to ensure that the end product of our process is a publishable draft of substantive quality.

If I had a classroom of students, I might even devote some class time to projecting Chat-GPT on the screen and walking students through various prompts – including showing where the program fails to make substantive comments or makes errors.

A fun picture of the Krakow dragon with Polish pierogi – and butter cubes randomly scattered on the table, a wizard possibly inspired by Game of Thrones creator David Benioff, and a knight with a sword perhaps growing from his chest.

I might even start with AI image generation as a more obvious way to show its fundamental flaws. I once, as an experiment, asked Chat-GPT’s image generator to produce an image of the legendary Dragon of Krakow guarding a cauldron of Polish pierogi. The result was a fun image – but showed a cauldron filled with what appeared to be American apple pies – round with lattice crusts. As the word “pierogi,” when referring to Russian pierogi, is often rendered as “pie” in English, the system had gotten confused. Asking it to replace the pies with proper images of half-moon shaped pierogi topped with butter and cracklings resulted in that problem being satisfactorily fixed. However, in the new image, several new problems appeared – including a knight with three swords and a tiny wizard hiding behind a pint of ale. Asking the AI why it had done this, it replied that it felt the narrative of the image had been improved, although it couldn’t tell me how these new characters related to Polish culture or mythology. Again, AI can only guess at these things. Its propensity for mistakes is still enormous.

We could make the experience even more tactile by imagining that we are at an AI-driven restaurant where our meals will be made by robots based on our prompts (not really so far-fetched an idea now). If we ask it for Polish pierogi and receive apple pie, we have every right to be upset and to send it back for correction. If we ask it for a chicken dinner and receive a metal pan of dry grains, we should also be upset and send it back for correction. We should already know what a quality outcome will look like and should not expect to consume an output without question.

Image generation is much easier to question than text generation. We can still instinctually agree on what pierogi and humans and chicken dinners should look like. However, a strong argument not based on fallacy and even correct historical or scientific facts are not things that we can all instinctually identify. This can only come with education and training. Further, even with current strides in AI, these things can also only confidently come from an educated and experienced human.

The best way forward with AI is to make sure that students not only know what it is – a powerful tool with substantial limitations – but also to ensure that students receive strong instruction and intensive practice on how to write, research, and edit. No matter how much we advance technologically, these skills will remain timeless and essential.

You’ll Also Love

AI in Publishing and Education

As someone who works in publishing and with student authors, I have had the opportunity to both work with generative AI and with students working…

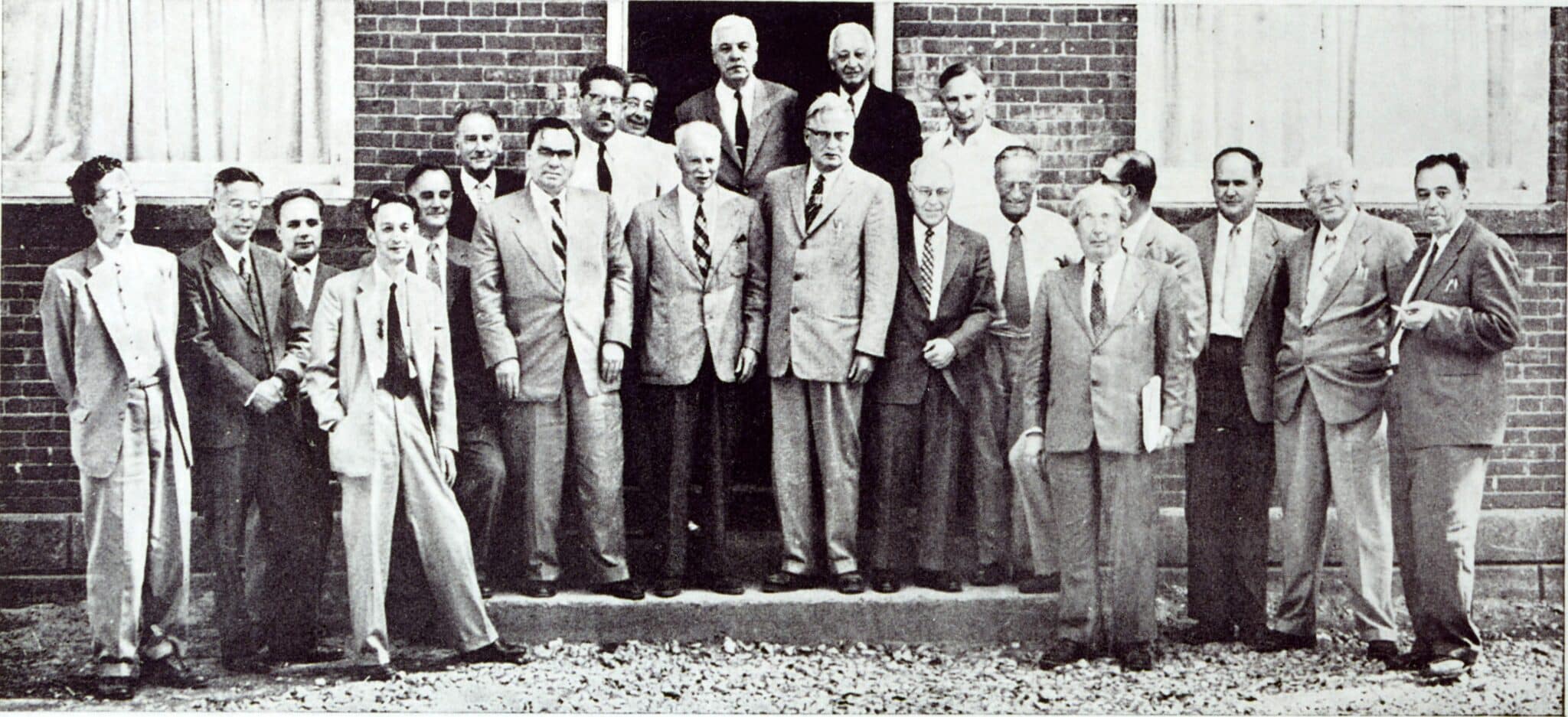

Book Review of From Pugwash to Putin: A Critical History of US-Soviet Scientific Cooperation by Gerson S. Sher

Gerson S Sher, From Pugwash to Putin: A Critical History of US–Soviet Scientific Cooperation. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2019. 318 pp., $80.84 hb. ISBN-13 978-0253042613 …

5G Networks in Russia: Development and Trajectories

Technology is constantly evolving, utilizing ever more bandwidth and making ever more connections between people and devices. Because of this, new cellular networks are needed…

Artificial Intelligence in Russia

Artificial intelligence has been rising in practical uses for the past several decades. From smart devices to automated weapons, it has changed the way humans…

Symmetry in State Surveillance: The US and Russia

The growth of technology and Internet-connected devices has made the surveillance of individuals increasingly possible and common. Governments use surveillance to track individuals for a…