Transportation infrastructure is crucial to the economy of any country. At its most elemental level, an economy is a network of goods and services moving from one set of hands to the next. Roads, railways, airports, and ports greatly increase the number of hands that can be reached. This boosts competition and usually increases efficiency.

Russia has long been held back by infrastructure challenges. For much of modern history, Russia has been considered “backwards” in this regard. Today, however, progress is being made. In 2010, the World Economic Forum ranked Russia’s infrastructure 47th out of the 148 countries assessed by the study. By 2018, that ranking jumped to 35th. Some of the improvement came from Russia’s heavy investment ahead of hosting major events such as the 2018 World Cup. In addition, President Vladimir Putin has promised that significant investment will continue as part of a series of national projects.

Russian government meeting on infrastructure development

Infrastructure Basics

A country’s transport infrastructure typically begins with its rivers. These naturally occurring transport and communication networks allow an economy and society to develop to a point where the construction and maintenance of man-made infrastructure is affordable for additional growth and development.

Russia’s major rivers flow mostly from north to south, while its population—and therefore much of the economic activity—is distributed from west to east. Furthermore, Russia’s relative lack of mountains means that many rivers don’t have enough force and direction to be commercially navigable. They are often not deep enough, wide enough, or straight enough to be efficient enough for commercial shipping. Russia’s harsh winters and extensive permafrost mean that water shipping is also not available for some or all of the year in many places that rivers exist.

The lack of initial development that resulted from this geographical situation is compounded with other problems. For most of its history, Russia has suffered from long distances between its cities, a perennial shortage of materials needed for modern roads and rails, weather and soil conditions that make building and maintaining infrastructure difficult, and government inefficiency that adds costs to the already monumental sums required for development.

All of this means that most infrastructure developments cost a good deal more for Russian than for many other countries, measured as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). However, Russia still achieves a respectable economic multiplier from investments made. This metric holds that each unit of GDP invested into infrastructure should results in additional GDP growth. It usually holds true. Russia’s infrastructure economic multiplier for 1995-2016 was 2.3, nearly equal to Western Europe or Australia, which both averaged about 2.4. The economic multiplier is what makes the announcement that Russia will soon be pouring money into infrastructure cause for hope that Russia might be able to spread development to more of its vast territory and large population.

Russian Roads

Russian roads have long had an infamous reputation. Where they existed, they were often crumbling or unpaved, and insufficient for major traffic. Perhaps most strikingly, while the Trans-Siberian Railroad is still considered to be one of Russia’s major achievements, the Trans-Siberian Highway was only completed in 2015, more than 110 years later. The highway, which is actually a series of connected roads, represents the first time that one could travel a continual stretch of paved road from St. Petersburg in the far west of Russia with Vladivostok in the far east.

Russia has lagged in many other road categories as well. In 2000, the country had just 365 kilometers of expressway (high speed road), mostly centered around Moscow. Germany, meanwhile, currently has the world’s longest expressway system – totaling 12,996 kilometers — for a country about 48 times smaller than Russia. During the presidency of Vladimir Putin, Russia has added 2,050 kilometers, including an ambitious ring road for Saint Petersburg, and an expressway between it and Moscow.

In the state’s planned road construction for 2020-2030, two key focuses will be linking Siberia and the Far East with European Russia, as well as making driving routes between major cities easier.

A highway in Moscow. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Most reporting on the plans have focused on two of its most massive projects. One of these is a new expressway along the Black Sea coast due to cost some $19 billion. The road will link Russia’s resort areas with a beautiful seaside drive meant to be a tourist attraction in itself. Passing through the Caucasus Mountains, the project will require no less than 43 bridges and overpasses, as well as 27 tunnels. It is a lot of work for a relatively small stretch of road, making it quite likely that additional concerns such as providing military access to the sensitive North Caucasus region and providing that region with increased funding and development played roles in the decision to go ahead with the project.

Another ambitious new highway will run from the Kazakh to the Belarusian border. Known as the Meridian Highway, it will connect with Chinese projects meant to run between China and Europe. Russia’s section of the project will cover 2000 kilometers of Russian territory (equal to about three quarters of the width of the United States). Russia hopes to profit from the customs duties on cargo and the tolls collected by the road in addition to spurring the economy of surrounding regions by creating jobs and easing transport.

While these centerpiece projects are impressive, total spending on roads is expected to reach an allocation of $73 billion over the next six years. Much of this money will go to smaller projects for roads and bridges that provide improved connectivity to an array of regional resources and populations.

FIFA World Cup and Other Events as Infrastructure Drivers

Russia has been using major international events to focus spending and resources on developing infrastructure in specific cities. The 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Vladivostok, the 2013 Summer Universiade in Kazan, and the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi all saw massive infrastructure spending in and around those cities in preparation for their global showcasing. The Winter Olympics, for instance, cost an incredible $51 billion. However, only about a sixth of those funds went towards Olympic facilities. Most of the money went to developing Sochi’s public transit, traffic follows, regional connectivity, sewage treatment, power plants, small and medium business, and many other areas that had been neglected since Soviet times.

Krestovsky Stadium in Saint Petersburg

Preparation for hosting the 2018 FIFA World Cup was particularly interesting because it focused on several major cities and, more importantly, the connections between those cities. Russia won the right to host the tournament in part with its promise to spend billions on necessary infrastructure. The sheer amount of material needed for stadiums, rail stations, bridges, rails, and other projects necessitated erecting an entirely new steelworks in Chelyabinsk.

In total, transport and utility infrastructure built for the FIFA World cup totaled $6.1 billion. These outlays are considerable, but the results have also been substantial.

Railways and roads were a major focus of this, both within and between host cities. Saint Petersburg and Nizhny Novgorod both extended their long-stagnant metro system metro systems. Host city Samara, meanwhile, received a new tram line which terminates at the football stadium. In Yekaterinburg, funding finally arrived for the completion of a ring road around the city and general modernization of the road system. Rail connections between the cities were improved with new or renovated stations. In addition, aging, stuffy trains that ran between most host cities were replaced with new, modern cars and specially trained staff.

Airport infrastructure constituted the most significant single item in infrastructure development for the World Cup. In the decade leading up to the World Cup, capacity was doubled for Saint Petersburg’s airport and Moscow’s three major airports in 2015. During the event itself, a temporary terminal put in place at Saint Petersburg’s Pulkovo Airport saw a huge increase in passengers for the tournament. In Moscow, much of the focus was on upgrading existing infrastructure. Kaliningrad, an enclave that was dependent on air travel for its connection to other Russian host cities, had a new domestic terminal built, while Yekaterinburg’s received similar attention. Rostov-on-Don got a brand-new airport. Finally, Kazan and Sochi’s airports underwent radical expansions, with capacity in those cities quadrupling.

Overall, hosting the 2018 World Cup and other events have helped lend some urgency to the mission of upgrading Russian infrastructure. While many of the projects were made necessary by the upcoming events and the need to radically expand capacity, they will nonetheless likely continue to reap benefits for domestic travel and business, as well as future tourists.

Railways and Economic Hubs

Russia has shown that is serious about connecting its major cities into larger economic hubs. Russian Railways has set out an ambitious plan for expansion, including acquiring more rolling stock, building and updating railway, and creating high-speed lines. Rolling stock, or the locomotives and carriages used on railways, is especially an issue, because Russia currently does not have enough and cannot acquire more fast enough. This is a particularly important issue given that one of Russia’s major growth industries right now is agriculture, and industry that relies heavily on efficient transport to move its product to market in limited time periods.

Bridges are, again, playing a large role in this development. A massive and geopolitically controversial rail bridge is now being completed across the Kerch Strait to Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014 from Ukraine. Once complete, Russia will have rail access to Crimea’s five major sea ports, alleviating strain on Russia’s overstretched port system and allowing additional outlet for Russian exports heading abroad. Outside of the spotlight, many other significant bridges are planned, such as one that will cross the Lena River. It will connect Yakutsk, a city of nearly 300,000 (the largest in northern Siberia), to direct rail access for the first time.

Russia is also working to move towards high-speed rail. Russia’s first high speed rail service opened between Moscow and Saint Petersburg in 2009. Serviced by Sapsan trains, (which translates to “falcon” in Russian), passengers travel the line at 155 miles per hour. The service cut travel times in half and has become the most profitable rail line in Russia.

Although Russia is now running high speed trains (others include the Allegro, Lastochka, and Strizh), it still lacks high speed track. The Sapsan can actually travel at some 220 miles per hour, but older tracks, built for older trains, bend too often and sharply for such speeds to be safe.

The Sapsan train, operating between Saint Petersburg and Moscow

Russia’s first true high speed line is due to be built between Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod before being extended to Kazan. On this new line, bullet trains will reduce the travel time between Moscow and Kazan from fourteen hours to about three. The project calls for some 400 miles of new high-speed rail.

The government approved the project in May 2013, but it has encountered a number of difficulties since then, with construction currently limited to a small test section. Estimated completion dates also continue to be pushed back, and currently estimate the first section opening in 2024. In particular, the presence of Western sanctions has made it nearly impossible to obtain financing for the project from European banks. In the absence of Western investment, the slack has been taken up by Chinese and Russian investors (including the government) and the BRICS New Development Bank. Russian state funding includes government spending as well as investments from the pension fund and the national wealth fund. Other non-state investors include the China Railway International Group, JSC Sogaz Insurance Group and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

While many agree that the estimates may be high, Russian rail predicts that in the first year of operation, the new line will serve 10.5 million passengers. That number increases to 20 million in 2035 and 25 million in 2050. Russian Railways’ optimistic estimate for GDP growth as a result of the project is $109 billion through 2030. They further estimate that regional growth in Vladimir and Nizhny Novgorod will increase by 58% and 76%, respectively. The hope is to create an economic hub between Russia’s first, second, fifth, and sixth largest cities, allowing, greater efficiency and interconnectedness for their economic activity.

Critics of these estimates think that people who can afford faster travel will continue to fly, while those traveling on more of a budget will continue to buy tickets for slower trains. However, foreign tourists are more likely to now include both Moscow and Saint Petersburg on their trip itineraries given the convenience of train travel – which does not necessitate the extra time and expense of traveling back to an airport. Indeed, there are already international tourist agencies that advertise for Kazan. Furthermore, part of the advantage to the construction of the new line is that old lines will be free to be used for more cargo traffic.

In the future, there are plans to extend the high-speed rail line to Yekaterinburg (Russia’s 4th largest city) and Chelyabinsk (7th) in the Ural Mountains, and from there all the way to Beijing. In this way, the project could be tied into China’s much-discussed “One Belt, One Road” initiative, connecting Asia and Europe. Chinese financing is indeed projected to provide a good deal of capital for the project, although now some Russian and Chinese officials alike are expressing concern about the size and conditions of the outlays. Such a high-speed line would cut train travel time between Moscow to Vladivostok from six days to only two.

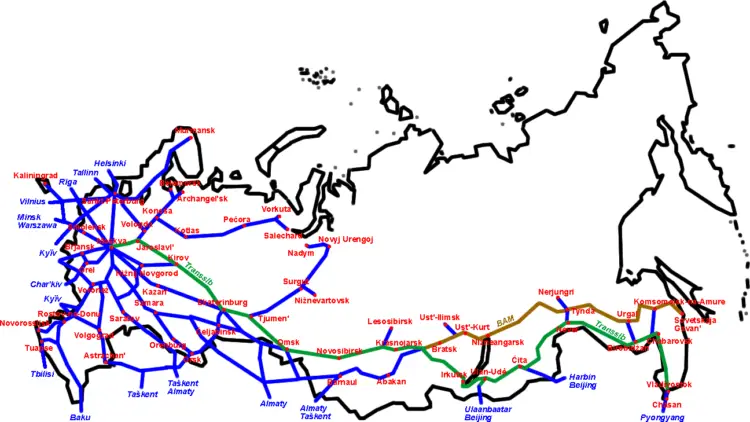

Map of railways in Russia

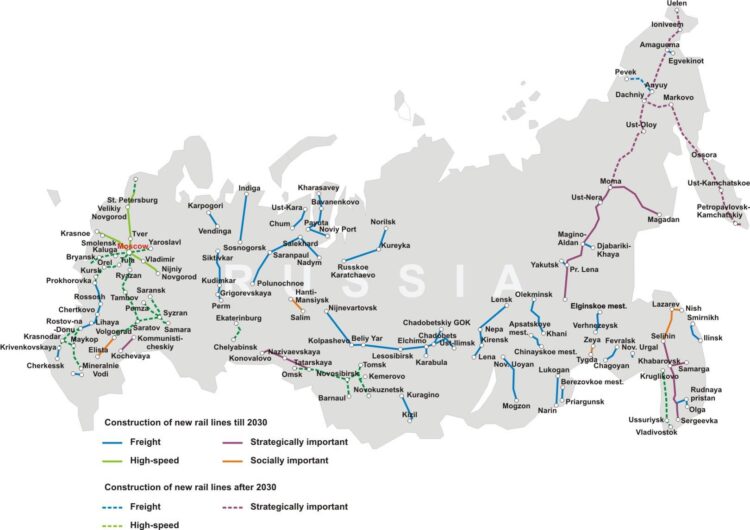

Planned new railways for Russia through 2030 and beyond. Much of Russia, including the Far East and Siberia, will see rail development for the first time.

Development in the Arctic

A discussion of Russian infrastructure would not be complete without touching at least briefly on the Arctic region and Northern Sea Route. Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev recently confirmed that the Arctic is considered a vital region by the Russian government—in terms of natural resource extraction, shipping, and national security.

Russia’s long coastlines have been relatively worthless to it for most of its history. To the east, access to the Pacific is blocked by a thick wall of mountains. The northern coast has long been blocked by ice. However, the situation in the north is now transforming as climate change has led to drastic reductions in sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. As a result, Russia’s northern coast has become free of ice for increasing parts of the year. The route along this coast is called the Northeastern Passage, or the Northern Sea Route. Currently, it is usable for about three months of the year and reduces shipping times between Asia and Europe by about two weeks compared to using the Suez Canal. Shipping has quadrupled along the Northern Sea Route since 2013.

Although there are strong environmental and safety concerns over developing the route, Russia has set ambitious targets for doing so. A recent government report says that an additional $162 billion is needed to update and create infrastructure to allow those targets to be met. Planned projects include new airports, seaports, railroads, highways, and pipelines. Arctic ports have particularly benefited from the new focus on the region. A $1.7 billion extension to the Sabetta railroad in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug is in the works. It will become the world’s northernmost railway. The port of Sabetta is intended to become a major economic center in the region, with particular emphasis on export of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

A ship makes its way through the ice outside the port of Sabetta

In late 2017, the Yamal LNG project was launched. While it is still building up to its 16.5 million ton capacity, a second LNG facility has now been announced for the Okrug, which is one of Russia’s largest producers of natural gas. In fact, no less than seven large LNG terminals have been built or are planned. Further, a shipyard is being built in Murmansk that will help produce floating LNG facilities for the Arctic. All these new facilities will likely benefit from the development of the Northern Sea Route.

Overall, Russia has moved to leverage its vast northern coastline to its economic and geopolitical advantage, but potential problems remain. Much investment has also gone into developing Russia’s fleet of icebreakers. These ships are crucial for shipping in the Arctic, as ice can still trap container ships even with the clearer seas. The Northern Sea Route (and the Arctic Ocean in general) is quite shallow, which presents issues for large, modern container ships that are usually preferred by Chinese shippers. These currently run much of Asia-Europe trade that should be the route’s main income source. There is also a risk that infrastructure development will not be enough, as there is so much to build and update, both along the northern coast and in the resource-rich Siberian and Far East regions.

Much more on the Northern Sea Route and the infrastructure going into it can be read in this article, also on GeoHistory.

Looking forward

Russia’s development has long been impeded by its geography and the vast, often empty distances its infrastructure must cover. Economic policy in Russia over the last several years has also faced the additional challenge of adapting to and countering sanctions. Even so, infrastructure development has continued both gradually and in large steps coinciding with major events like the World Cup. Looking at President Putin’s twelve National Projects and the planned increases in government spending on infrastructure, in conjunction with private and foreign partners, one can easily imagine that the modernization will continue. Indeed, it is imperative, if Russia’s economy is to continue growing and if it is going to make the next step in improving the quality of life of its people.