“Municipal solid waste,” or “MSW,” is the technical term given to “garbage consisting of everyday items used by the public.” Managing MSW is increasingly a challenge worldwide; however, the degree of sustainable waste management varies by country.

In recent months, thousands of residents living in Moscow’s suburbs have taken to the streets to protest the condition of local landfills. In Volokolamsk, for instance, dozens of local children were hospitalized with respiratory ailments, rashes, and other conditions most likely caused by pollution that locals blame on the landfill, which is located near residences. Other protests have also focused on the inconvenience and/or potential danger posed by local landfills.

Many of the current problems facing MSW in Russia arose after Putin’s decision in the summer of 2017 to close the Kuchino landfill, one of largest serving the Moscow region, due to overcapacity and growing pollution concerns. As a result, the capital, which produces the largest amount of MSW in the country, was left short of space to dump its trash and began diverting waste to other suburbs. Protests similar to those in Volokolamsk also took root in other Moscow suburbs like Kolomna, Klin, Tarussa, Tuchkovo, and the districts of Voskresensk and Naro-Fominsk.

Residents protest the increasingly dangerous landfills surrounding Moscow. Placard on the left reads, “Get Moscow’s garbage out of Volokolamsk,” and on the right, “Moscow take away your garbage!” Photo originally featured on the Guardian.

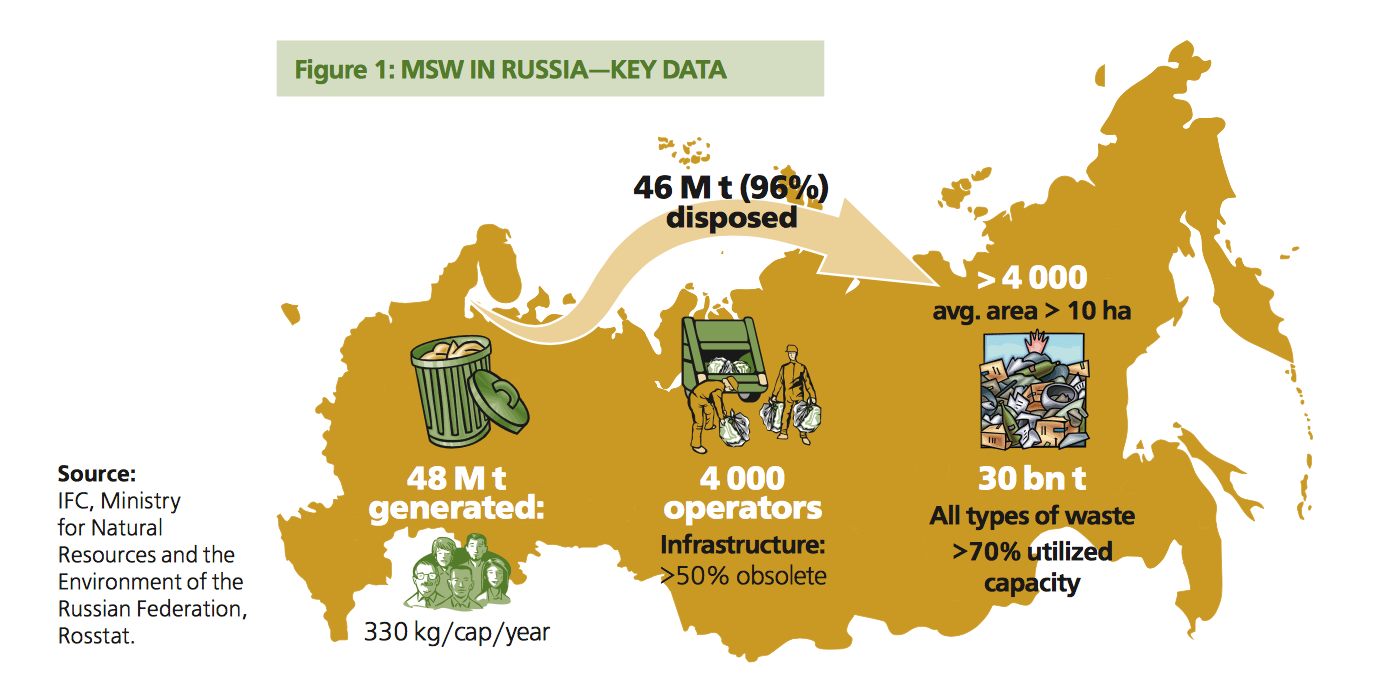

Solutions are possible – but will require political will and substantial investment. Whereas the EU on average recovers approximately 40% of its waste as reusable materials, and 20% as energy, Russia currently recovers only 4% of its MSW total. Instead, 96% is disposed of, without sorting. As landfills are pushed beyond capacity, air quality diminishes, and environments can become toxic. This paper will explore further Russia’s current waste management system, as well as the challenges and opportunities for future sustainable development.

Defining the Problem

The Soviet government developed large scale recycling programs during the 1970’s. During the 1980’s, almost 30% of all paper used was recycled. Further, consumers routinely visited glass recycling centers to return glass bottles. During the 1990’s, as the USSR collapsed, most of its social programs, including recycling, also collapsed. As subsidies and official support were withdrawn, the Russian system of collecting scrap metal, waste paper, recycled textile, and glass was abolished.

Following the years of heavy market reform during the Soviet era, consumption, especially among Russia’s urban populations, increased in tandem with the use of plastics in the production and sale of consumer goods. Now, these plastics, along with other packaging materials which were once recycled are collected as trash, without sorting, and transported directly to the landfills, comprising Russia’s largest source of waste.

As a result, between 2000 and 2015, disposal into Russian landfills nearly doubled, from 151.2 million to 282.3 million cubic meters. The numbers are continuing to rise; The World Bank’s estimated in 2012 that current Russian landfill space is already 65-70% full. If waste generation continues to grow, by 2025, Russia will need to double its capacity to accommodate waste.

Images taken from the World Bank’s summary report of MSW Management in Russia.

Further, 50-70% of current infrastructure is obsolete, and many formal collection services do not extend to small towns and villages in Russia. As a result, unauthorized dumping is becoming more common, in which waste is illegally deposited in large quantities onto land without a license. According to The Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resources, 17,500 illegal dumps exist in Russia at present.

Without environmental monitoring, such sites present health risks for local populations. An example can be seen in Port Baikal in the Irkutsk region; when waste collection came to a halt in 2008 during a budget crisis, unauthorized dumps eventually resulted in typhoid epidemics, as solid waste was dumped near a water source, becoming a breeding ground for pathogens and resulting in contamination.

Of Russia’s 7153 authorized landfills, 30% do not meet sanitary requirements, and many are already overfull but are still accepting new trash. Environmental violations often include a lack of sanitary protection zones, drainage systems, and purification systems for rainwater, as well as water-resistant screens to prevent run-off and leakage issues. Short term environmental impacts include spontaneous combustion resulting from biogas emissions (methane and carbon dioxide), as well as landfill fires and the littering of surrounding lands. In the long term, risks include decreased biodiversity and soil fertility, as well as the contamination of aquifers by toxic substances contained in leachate, a substance formed when waste degrades and rainwater reacts with the resulting organic and inorganic chemicals, heavy metals, and pathogens. In landfills without leachate filtering, the liquid directly enters the soil and can penetrate ground water as well as open reservoirs, resulting in poisoned water sources.

Unauthorized dumping area in an abondoned building in the city of Irkutsk.

Challenges and Opportunities

MSW management in Russia will need to be improved in two major areas: 1) management of existing landfills and dumpsites, and 2) optimization of MSW systems for future waste, specifically at the stage of collection, in order to increase waste recovery.

In properly managing Russia’s current MSW infrastructure, several additional factors must be considered. These include: equal access to quality waste management services among Russia’s population; environmentally safe waste treatment methods; and the reduction of raw inputs in production in order to reduce disposal volumes. Thus, sustainable waste management development will necessitate significant resources as well as political and social will.

Russia has faced difficulty in developing a strong, consistent legislative framework for reforming its waste management strategy. The earliest framework existed between 1996 and 2000 as a federal target program; however, it provided little direction or support, and its goals were not achieved. Reforms in 2004 tried a different direction, delegating responsibility for solid waste management to the municipal level. This was part of a general reform push to encourage localities to resolve their own problems. However, for MSW and other issues, municipalities generally lacked the financial resources, experience, and investment opportunities to create the infrastructure needed to resolve the issues at hand. Thus, the reforms of 2004 were also largely unsuccessful. 2011 saw an order for executive authorities at regional and local levels to prepare long-term, targeted investment programs for waste management; however, the mechanisms for attracting private investments in the sector of solid waste were not defined. Thus Russia has continued to rely on landfilling as its primary waste management strategy.

Russia’s potential for MSW recovery varies geographically, as technology and economic resources differ throughout the country. Source: World Bank’s summary report of MSW Management in Russia.

In recent years, new legislative and economic measures are providing hope for the improvement of Russia’s waste management system. In 2013, the Ministry of Natural Resources approved an integrated strategy for the treatment of MSW, set to take place between 2013 and 2030. The strategy will focus on improving MSW regulatory frameworks and mechanisms for economic regulation, as well as developing material, technical, methodological, and informational support for the development of new MSW systems.

These measures are set to have economic bite. These include charging residents for waste disposal, offering incentives for effective waste management development and charging regional waste operators for negative environmental impacts. Additionally, in 2014, the responsibility of waste management was once again redistributed, this time to include federal, regional, and local powers. Such changes provide the opportunity for success by combining federal power and resources with local and regional knowledge.

The goals at hand face challenges – first and foremost in the financial resources required to achieve them. However, the figures needed are surprisingly manageable. According to the International Finance Corporation (2012), the capital investment required to improve the current waste management system, such as landfill control systems, rehabilitation and sanitary improvements at existing sites, the closing of disposal sites currently in poor condition, and the upgrade and extension of truck and container fleets, numbers around €18.5 billion (~$22 billion). Further, the capital required to establish a new, fully sanitary system of waste treatment and disposal by 2025, would require an additional €33.5 billion. Comparatively, the current cost of maintaining a disposal-oriented approach numbers around €30-35 billion per annum. Clearly, projected investment figures are not astronomically above current MSW system costs, providing incentives to pursue resource and energy saving alternatives.

The final factor to consider in Russia’s plans for MSW improvement includes the feasibility of a unified approach to waste reform. While locally driven attempts to reform waste management previously failed due to lack of federal resources and guidance, a fully unified approach also poses challenges. The economic and geographic diversity of Russia’s municipalities necessitate alternative, tailored approaches to waste reform, depending on local and regional needs. This is highlighted by the fact that at present, there exists a large discrepancy in the levels of progress of local MSW projects across Russia; some regions, such as Nizhny Novgorod, have already announced the successful development of new waste management systems, while others have yet to begin preparatory activities. Thus, successful intergovernmental cooperation will be critical will be in order to match federal resources with local need.

Woman protests dangerous landfills in the Moscow region. Photo originally featured on the Guardian.

Conclusion

Increasing levels of waste production, the presence of illegal dumpsites, diminishing landfill capacities, landfills located too near residential areas, and other environmental hazards currently drive Russia’s pursuit of a sustainable municipal solid waste management system. While since the turn of the century, Russian municipalities have lacked the legislative frameworks, methodologies, and financial resources, the recent reorganization of MSW management responsibilities and the creation of an integrated strategy for the treatment of MSW provides the opportunity for future successful development. However, in order to realize such potential, Russia’s federal and local governments – as well as its people – must be willing to work together to make the financial investments and social changes necessary. Such opportunities, coupled with growing social movements focused on urgent local programs such as MSW, will thus hopefully drive the country towards more sustainable MSW systems in the future.