In the months leading up to Russia’s most recent state Duma elections, ‘Just Russia’ party leader Sergei Mironov demanded that the country have the option to vote “against all,” describing it as a “barometer of society’s well-being” (Ria Novosti 2011). Five years prior to this, “against all” was removed from the Russian ballot, despite its popularity. In the single-mandate constituencies of the December 2003 Duma elections, more than seven million Russians voted “against all.” With nearly 13% of the vote that year, “against all” received more votes than all but one of the parties. In fact, since 1991, Russians had been increasingly registering their discontent by choosing to vote “against all.” Since 1997, the people could also feel that casting an “against all” vote mattered; elections where “against all” received more votes than any one candidate were declared invalid and repeated. Though the integrity of elections in post-Communist Russia has clearly fallen over the past few years, other post-Communist countries have demonstrated their commitment to democratic elections by taking up the “against all” barometer.

This study examines the “against all” vote in the 2010 Kyrgyz parliamentary elections as an example of protest voting in post-Soviet elections. The analysis proceeds by first investigating whether there are common characteristics found amongst people who vote “against all.” In order to do this, common characteristics found amongst Russians who voted “against all” in Russian elections until 2005 are tested in the context of this Kyrgyz election. Specifically, this study tests the relationship between votes “against all” and urbanity, education, ethnicity, and exposure to violence. The analysis then proceeds to investigate whether votes “against all” in the Kyrgyz election were highly dispersed or if they were concentrated in small pockets of the country, and what reasons could account for this distribution of votes.

Protest Voting

Voting “against all” is just one type of protest voting, which assumes different forms in different countries. France, Spain, Colombia, and Greece have a tradition of “blank voting,” where one submits a ballot without having chosen a candidate. In Spain, blank votes are formally counted and accepted as votes separate from those considered “spoiled.” In France, blank votes are not recognized formally. However, in 2011 a group of French citizens came together to form the White Vote Party that provides French voters with the option of casting their vote for a White Vote Party candidate. This distinguishes these voters from abstainers by allowing them to have their dissatisfaction recorded. Similarly, in the United Kingdom the None of the Above (NOTA) party has been running in parliamentary elections since 2000 with the sole aim of introducing a bill to the parliament that proposes to add the “None of the above” option be added to every local and general election ballot paper in the future.

Protest parties also seek to combat the type of protest voting behavior in which some voters choose to cast their support for radical parties in order to punish the mainstream parties for whom they feel resentment by providing a more focused, less radical outlet for that resentment. Grigore Pop-Eleches examined the phenomenon of protest voting for radical parties in post-Communist East European elections and found that significant electoral gains were made by radical parties over time. This was especially true in “third generation” elections – elections that take place after two significantly different ideological camps have had a chance to govern. Pop-Eleches concludes that radical parties have begun to benefit from dissatisfied voters and that, therefore, the party system has become unstable.

Johannes Bergh, on the other hand, examined protest voting as a form of “expression of political distrust at the polls” and tested to see if protest voting is aimed at mistrust of the political system or elites (2004). Bergh found that the phenomena in Austria, Denmark and Norway largely occur due to distrust of elites and concluded that this is a positive phenomenon, as it means protest voting and mistrust is directed towards individual authorities and not the political system. Kyrgyzstan’s parliamentary democracy is perhaps too young to tell whether votes “against all” are directed at the system or the political elites. However, it is worth noting that in post-Communist countries like Russia and Kyrgyzstan, personalities drive politics and the two are so entwined that perhaps a protest vote in the post-Communist world is a vote against the individual and the system.[1]

Against All

The vote “against all” is unique in that it is fundamentally different from simple abstention, but also more formal than other forms of protest voting. The voter takes on the burden of voting and legitimizes the electoral process by participating, but instead of contributing to the election of any specific candidate or party, the voter registers his or her protest by casting a vote “against all.” Derek Hutcheson describes this as a “positive negative vote” (2004).

Our understanding of the role of the vote “against all” in post-Communist Russian elections comes from three major studies done by Derek Hutcheson (2004), Ian McAllister and Stephen White (2008), and Hans Oversloot, Van Holteyn, and Ger P. Van Den Berg (2002). Oversloot, Holteyn, and Van Den Berg enrich the subfield by weighing the pros and cons of the “against all” option. On the one hand, they argue that having the option can increase voter turnout, maintain legitimacy, and work as a democratic “safety valve.” On the other hand, they point out that in party-list elections [2], votes “against all” can have the perverse effect of distributing seats among fewer party lists, thereby consolidating power in the hands of the candidates with whom the “against all” voters are dissatisfied. This, the authors argue, makes the system of proportional representation less proportional, and they remind their audience that the voting option can only serve to register discontent — not remedy it. Because the Kyrgyz Republic relies solely on party-list elections, these last arguments are important to consider.

Hutcheson offers the most thorough profile of the “against all” voter (2004). In his study of individuals who voted “against all” in Russian parliamentary elections, he tested the relationship between the likeliness to use this protest option and urbanity, age, and education. His study finds that those who are located in or closer to a big city, or have higher levels of education, are more likely to vote “against all” than those who are rural and have achieved lower levels of education. This paper will investigate whether or not these characteristics are found amongst Kyrgyz voters who chose to vote “against all” and also find whether ethnicity and exposure to violence increase the “against all” vote.

The Kyrgyzstan Case

The 2010 parliamentary election took place under Kyrgyzstan’s newly adopted constitution. Earlier that same year, the country had experienced a revolution which had several repercussions: the toppling of President Kurmanbek Bakiyev; the installation of an interim government under President Rosa Otunbayeva; an outbreak of inter-ethnic violence between Kyrgyz and Uzbek citizens that resulted in the death of hundreds or possibly thousands[3] in Kyrgyzstan with ethnic Uzbek minorities bearing the brunt of the violence; and finally, a referendum which adopted the new constitution that transformed the Kyrgyz state into a parliamentary republic – the first in Central Asia. It is remarkable, then, that this parliamentary election was deemed the freest and the fairest in the region’s history (Huskey 2011). Table 1 shows the percentage of votes earned by each party and how many seats each party gained as a result.

Table 1. Results by Party for the 2010 Kyrgyz Parliamentary Election [4]

| Parties | Votes | % Votes by Eligible Voters |

Seats Gained | |

| Ata–Jurt | 257,100 | 16.1% | 28 | |

| SDPK | 237,634 | 14.55% | 26 | |

| Ar-Namys | 229,916 | 14.02% | 25 | |

| Respublika | 210,594 | 13.12% | 23 | |

| Ata-Meken | 166,714 | 10.13% | 18 | |

| Butun-Kyrgyzstan | 139,548 | 8.76% | — | |

| Akshumkar | 78,673 | 4.76% | — | |

| Zamandash | 55,907 | 3.82% | — | |

| Other Parties | 230,829 | 7.6% | — | |

| Against All | 10,839 | .65% | ||

| Not Voting/Casting Invalid Vote | 43.41% | — | ||

| Total | 1,617,754 | 120 | ||

As Table 1 shows, the nationalist party popular in the South, Ata-Jurt, was the top vote-earner with nearly 16.1% of the national vote. Two parties associated with the interim government, SDPK and Respublika, came in second and fourth with roughly 14% of the vote each. Ar-Namys, a formerly banned party favoring free market democracy and popular in the North, took third with another 14%. Finally, the percentage of the electorate that voted “against all” was 0.65%. This number may seem rather small compared to votes earned by other voting options, but this national district average conceals higher percentages of votes for “against-all” in various precincts. The rest of the analysis examines where, by whom, and for what reason these votes “against all” were cast.

This paper will rely on the 2010 Kyrgyz Republic Parliamentary Election results provided by Dr. Eugene Huskey and Dr. David Hill of Stetson University, as well as on the 2009 Kyrgyz Republic Census demographic data obtained by a colleague in the Kyrgyz Republic, as translated and systemized by Drs. Huskey and Hill. Kyrgyzstan had 56 districts in this election, but the election data set used here counts the city of Osh as its own district as well. It is important to note that Bishkek City is divided into four separate districts because of its size. Finally, survey data for Kyrgyzstan was unavailable at the time of this study, limiting the ability to make conclusions at the individual level. This study relies on election results at the precinct level and above. All demographic data is at the district level.

“Against All” Voter Characteristics at the District Level

In order to get a clear profile of those who vote “against all,” this study will test those characteristics found amongst Russian “against all” voters in the context of the 2010 Kyrgyz parliamentary election. Because Kyrgyzstan has two major minority groups, Russians and Uzbeks, who make up 8% and 14% of the country’s total population respectively, it is important to test for variation amongst ethnicities. Also, as mentioned previously, several regions of the country experienced intense inter-ethnic violence between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks just a few months before the election. For this reason, it is imperative to test whether or not the pre-election, inter-ethnic violence between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks had an effect on votes “against all” not only regionally, but also amongst Uzbek voters, who lost a disproportionate number of members from their communities during the turmoil. Based on the literature about “against all” voters in Russia, as well as in other protest literature, this paper proposes the following hypotheses for “against all” voters in Kyrgyzstan:

- In a comparison of districts, those with higher urban populations will be likely to have a higher percentage of votes “against all” than districts with lower urban populations.

- In a comparison of districts, those with a higher ethnic Russian or Uzbek population will be likely to have a higher percentage of votes “against all” than districts with higher Kyrgyz populations.

- In a comparison of districts, those with a higher percentage of the population with higher education will be likely to have a higher percentage of votes “against all” than districts with lower rates of higher education.

- In a comparison of districts, those that experienced violence in the June 2010 ethnic clashes between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks will be likely to have a higher percentage of votes “against all” than districts that did not experience ethnic violence.

Figure I. The Relationship between

District-level Urban Population and Votes “Against All”

Y = .003 + .004; P= .000

For this study, scatterplots plot Kyrgyz districts as individual cases. The regression line provides the predictive value for each case. The scatterplot in Figure I indicates that there is a positive relationship between the urban population and votes “against all,” suggesting that an increase in the urban population led to an increase in votes “against all.” Furthermore, the regression coefficient, which is used to indicate the change in the dependent variable for every one unit increase in the independent variable, suggests that for every one percentage point increase in the urban population, there was a 0.4% increase in votes “against all.” Considering the fact that this study is working within a small range of values, this impact cannot be dismissed as minimal. In fact, the R2 (which predicts to what extent the outcome can be explained by any proposed independent variable), indicates that a district’s urban population can explain a little less than 22 percent of the variation in votes “against all.” In keeping with Hutcheson’s findings, it can be concluded that districts with a higher percentage of urban residents also have higher percentages of votes “against all.”

Figure II. The Relationship between the Percentage of Those with

Higher Education at the District Level and Votes “Against All”

Y = -.001 + 6.256E-6; P = .000

Figure II shows the scatter plot of the linear regression between the percentage of the population with higher education at the district level and votes “against all.” The regression coefficient demonstrates a moderately positive relationship between these two variables. This becomes clearer when we consider that the R2 value tells us that the percentage of residents with higher education within a district can account for nearly 60 percent of the variation in votes “against all.” Because urbanity and higher education seem to be strong indicators of votes “against all,” we can assume that at least in some ways, Kyrgyz “against all” voters resemble their counterparts in the previous Russian Federation elections.

Figure III: The Relationship between District-level Russian

Populations in Kyrgyzstan and Votes “Against All”

Y = .003 + 3.915E-6, P = .000

Figure III displays the relationship between district-level Russian populations and votes “against all.” A moderately strong positive relationship clearly exists between the two variables; the higher the district’s population of Russians, the higher number of votes “against all” the district had. The regression coefficient reflects a moderately positive relationship. The R2 value further indicates that a district’s Russian population can explain roughly 61 percent of the variation in votes “against all,” a strong enough indication that while the concentration of Russians in urban, well-educated areas may cause some of this number, ethnicity also plays a role.

Kyrgyzstan’s Russian population and its opportunities for higher education are concentrated in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital and most urban city. Russians make up 28 percent of Bishkek’s population. Bishkek had a voter turnout of 55 percent and received 1,123 votes against all, roughly 2 percent of the votes. If we compare this to the district of Chon-Alai, whose population is nearly 100 percent ethnic Kyrgyz, we see that even with a voter turnout of 61 percent, there was not a single vote “against all.” We can use a scatterplot to make sure this holds true in other districts heavily populated with ethnic Kyrgyz.

Figure IV. The Relationship between

District-level Kyrgyz Populations and Votes “Against All”

Y = .017 -1.506E-6; P =.000

Figure IV displays a moderately strong inverse relationship between districts’ Kyrgyz population and votes “against all.” From the steep downward slope of the regression line, as well as the regression coefficient, it is clear that a moderately strong negative relationship exists between the two In fact, the R2 indicates that the percentage of Kyrgyz within a district can explain nearly 40 percent of the variation in votes “against all.” It is safe to conclude that districts more heavily populated with ethnic Kyrgyz are less likely to vote “against all.” From this, it is possible to conclude that the ethnic Kyrgyz population enjoys a certain level of satisfaction with the existing order, which often celebrates the Kyrgyz national identity.

Figure V. The Relationship between

District-level Uzbek Populations and Votes “Against All”

Y= .005 + .2.185E-7; P = .590

Figure V displays the relationship between district-level Uzbek populations and votes “against all.” The regression line shows that there was practically no relationship between the two. The magnitude of the regression coefficient is quite small, and the p-value suggests we have very little confidence that the slope is actually different from zero. This is further demonstrated by the fact that the R2 indicates that the district’s Uzbek population can account for only 0.5% of the variation in votes “against all.”. One might expect that this ethnic group, which bore the brunt of the pre-election violence, would have been more motivated to engage in protest voting behavior. A test of how exposure to violence is an influencing factor might be illustrative.

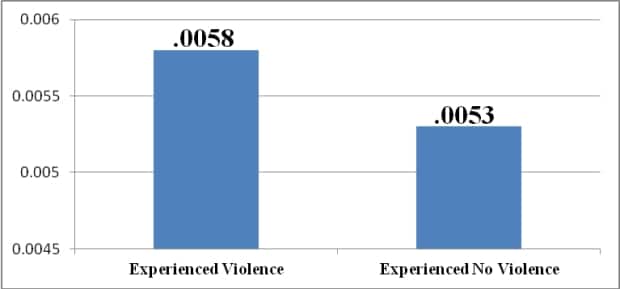

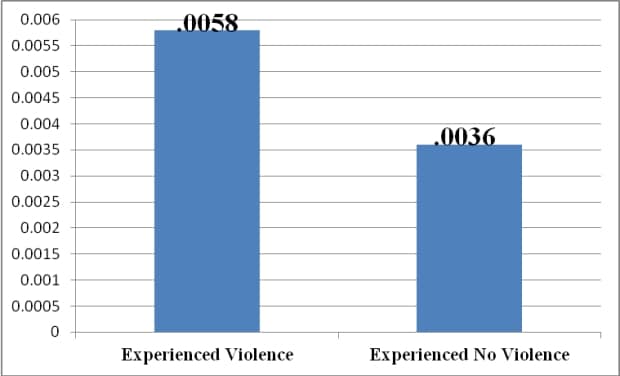

Figure VI. Difference of Means between Votes “Against All”

in Districts that Experienced Violence in June 2010 and Those That Did Not

The distinction becomes a little clearer if we control for regionalism because the violence was concentrated in the south.

Figure VII. Difference of Means between Votes “Against All”

in Southern Districts that Experienced Violence in June 2010 and Those That Did Not

Figure VI indicates that the mean estimate of the votes “against all” in districts that did not experience violence was roughly 0.5%, which puts it lower than the overall mean for the country. The mean estimate of the votes “against all” in districts that had experienced ethnic violence in June (as seen in both graphs) was closer to 0.6% and to the overall mean. Additionally, the t-test indicates that this difference is not statistically different from 0, and therefore it appears that the chance that a relationship between violence and votes “against all” is low. However, because this is an assessment being made at the district level, and only a few districts experienced violence, there is probably room for further examination at the precinct level. This is investigated in the following section.

Votes “Against All” and the Importance of Localism

Because the national percentage of total voters who voted “against all” was only 0.65%, and yet in some precincts the vote “against all” made up as much as 17% of the total votes, it seems the “against all” vote was not highly dispersed; rather, it was concentrated in small parts of the country. Out of 2,335 precincts, less than a quarter of them experienced votes “against all” equal to or higher than 1%. Table two displays the 15 precincts that had votes “against all” equal to or higher than 5%. Because the votes “against all” that came out of these 15 precincts accounted for more than 9% of the total votes “against all,” it is clear that protest voting was concentrated in just a few districts. Seven of the precincts with the highest votes “against all” were located in the Kara-Suu district of Osh oblast, adjacent to the Uzbek border. Four of the precincts were in the Suzak district, located in the Jalal-Abad oblast Two other southern precincts in the Uzben and Aravan districts of the Osh region had unusually high “against all” voting. The only northern areas to have a high percentage of votes “against all” were the Alamudun and October districts in Chui and Bishkek, respectively.

Table II. List of Precincts Where 5% of the Vote or Higher Went to Against All

| Precinct | Region | District | Raw Votes | Turnout | VotesAgAll | % AgAll |

| 5059 | Osh | Uzgen | 983 | 44% | 48 | 5% |

| 7164 | Chui | Alamudun | 1126 | 59% | 56 | 5% |

| 5169 | Osh | Kara-Suu | 870 | 59% | 42 | 5% |

| 2125 | Jalal-Abad | Suzak | 1000 | 45% | 58 | 6% |

| 5176 | Osh | Kara-Suu | 1259 | 77% | 79 | 6% |

| 2392 | Jalal-Abad | Suzak | 624 | 94% | 36 | 6% |

| 5269 | Osh | Kara-Suu | 718 | 42% | 48 | 7% |

| 2391 | Jalal-Abad | Suzak | 904 | 0.49 | 64 | 7% |

| 1154 | Bishkek | October | 908 | 105%[5] | 66 | 7% |

| 5521 | Osh | Aravan | 1357 | 76% | 109 | 8% |

| 5267 | Osh Reg | Kara-Suu | 899 | 4% | 83 | 9% |

| 5265 | Osh Reg | Kara-Suu | 596 | 41% | 77 | 13% |

| 2364 | Jalal-Abad | Suzak | 90 | 101% | 12 | 13% |

| 5503 | Osh | Kara-Suu | 693 | 45% | 95 | 14% |

| 5266 | Osh | Kara-Suu | 842 | 45% | 144 | 17% |

“Against all” received 7% of the vote in the October district in Bishkek, while the precinct in the Alamudun district of Chui (the oblast that surrounds Bishkek) received 5% of votes “against all.” It should not come as a surprise that two precincts from the Bishkek area would be among the top of the list for votes “against all,” because Bishkek has the highest urban population of any city in Kyrgyzstan and more access to higher education. It has already been established that districts with higher urban populations and levels of higher education see higher numbers of votes “against all.” It has also been established that districts with higher populations of Russians are likely to see higher amounts of votes “against all,” and Russians make up 28% of Bishkek’s population. The results for these two precincts are not difficult to understand.

More puzzling are the results in Kara-Suu and Suzak. These districts are both rural and located along the border that Kyrgyzstan shares with Uzbekistan in the Fergana Valley. Because these areas do not have a high urban population, a high percentage of the population with higher education, or a high Russian population, it seems that the established explanatory model fails to fully account for what happened in these two areas. Instead of demographic characteristics, we must instead take into account the recent political history in order to understand why the people in Kara-Suu and Suzak might have voted in such high numbers “against all.”

Over the past decade, citizens in the Suzak district have had many reasons to be upset with the ruling government. In May of 2005, hundreds of Uzbeks sought refuge in Suzak following a violent crackdown on protestors in Andijan, across the border in Uzbekistan. Protestors had met in Andijan’s Babur Square to demand that several local businessmen be released from prison and to voice anger over growing poverty and corruption within Uzbekistan. On the 13th of May, government forces sealed off the area and opened fire into the crowds, killing somewhere between 400 and 600 people and leaving hundreds more wounded.[6] Roughly 500 Uzbeks were able to cross the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border before Kyrgyz border guards turned away over 6,000 people. After a few weeks of housing refugees, Kyrgyz officials began to cooperate with the Uzbek government in returning many refugees back to Uzbekistan. Despite warnings from international observers like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees that Kyrgyzstan should not forcibly remove any refugees, somewhere between four and 29 refugees were officially extradited back to Uzbekistan. At other times, due to lack of protection, the refugee camp was stormed by crowds of Uzbeks who demanded that all refugees return to Uzbekistan immediately. The Jalal-Abad group “Justice” reported that Kyrgyz soldiers often stood by and watched as relatives of refugees forcibly tried to make them leave. “Instead of making the lot of these Uzbekistan citizens easier, respecting their rights and international norms of law and important documents which were ratified by our state, our authorities do the opposite,” some residents commented (Institute for War and Peace Reporting 2005). The same activists who had helped bring the interim government of Bakiyev to power were outraged at the decision to return refugees to an unstable country.

Five years later, in the months leading up to the country’s most recent parliamentary election, following in Bakiyev’s footsteps, the interim government would disappoint those in the Suzak district again. After several months of tension, violence between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz erupted in Osh on June 10, 2010 and spread to the Jalal-Abad region within days. Hundreds were shot, either wounded or killed, and many lost their homes to fires. It remains unclear if Bakiyev loyalists looking to stir up trouble for the interim government caused the violence just before the constitutional referendum, or if regional power struggles over drug trafficking in the region sparked the events. The violence is most often simply attributed to ethnic tensions. However, many agreed that the job of the interim government during that time was not to identify the culprits, but instead to secure the region and deescalate the situation. Many residents of Jalal-Abad claimed that local police forces were doing little to protect civilians and that they never saw reinforcements. One local ournalist reported, “There are no police or soldiers to be seen on the streets of Jal-Alabad, still less in outlying villages. We hear that reinforcements have arrived but no one has actually seen them. The curfew isn’t being observed, and gangsters and looters come out at night to rob the citizenry,” (Institute for War and Peace Reporting 2010).

Some 80,000 people fled Kyrgyzstan for Uzbekistan, and more than half of these were from Jalal-Abad. Some of the ethnically Uzbek villages in Suzak received the worst damage in Jalal-Abad oblast’, and people were forced to mobilize in an effort to restore order. Like the events of 2005, Kyrgyz and Uzbek government officials cooperated in sending refugees back to their home areas, even when Kyrgyzstani Uzbeks were still desperately trying to make it across the Uzbek border. For all of these reasons, it is certainly possible that people in Suzak were deeply disappointed with the government and chose to translate their dissatisfaction into votes “against all” in the October parliamentary elections.

Elsewhere, in the Kara-Suu district of the Osh Region, one precinct saw 17% of the vote placed for “against all.” Here, too, it is worth examining the political history of this region in the decade prior to the vote in order to attempt to explain this voting behavior.

Kara-Suu is the capital of Osh District and is located only 15 miles north of the city of Osh. Similar to those in Jalal-Abad, people in Kara-Suu were surprised when government officials failed to send enforcements to quell the ethnic clashes in June of 2010. Like residents of Suzak, many fled to Uzbekistan only to be returned home prematurely and against their will. In addition, reports have often come out of Kara-Suu with descriptions of leaflets, brochures, video tapes, and books found on persons that are classified as propaganda, radical, or sometimes even terrorist material. A radical Islamic party called Hezb-ut Tahrir, which is banned in Kyrgyzstan, is said to have some 3,000 active members in the Osh region, and some believe that this movement influences many young people in the district of Kara-Suu (Institute for War and Peace Reporting 2010). If this is true, some citizens in Kara-Suu might not identify with, nor be able to support, secular parties or candidates, prompting them to vote “against all.”

It is likely that residents of Kara-Suu mobilized the “against all” vote. Kara-Suu has been known to pull off major mobilization efforts in the past. In his article on localism in the district of Aksy, Kyrgyzstan, Scott Radnitz tells the story of a parliamentary deputy and later member of the Interim Government, Azimbek Beknazarov, who was tried on fabricated charges and whose communities of Aksy and Kara-Suu rallied around him. Volunteers joined Beknazarov in a hunger strike, held their children from school, and gathered over 5,300 signatures demanding that Beknazarov be released from prison. Though volunteers from Kara-Suu made up only a third of the total volunteers from districts supporting Beknazarov, Radnitz writes that “Kara-suu had a higher degree of what are often called ‘fanatics’ or ‘firstmovers’—those who voluntarily and zealously recruit people for their cause—than other villages,” (2005). He also claims that in Kara-Suu, the events around Beknazarov became an all-consuming obsession, and even people who were uninterested found it impossible not to participate in discussions. This anecdote is illustrative of the possibility that Kara-Suu residents might have been mobilized in a similar fashion to vote “against all.”

Conclusion

Studies that have examined those who voted similarly in Russian elections provide a framework for understanding who votes “against all.” This study found that Kyrgyz “against all” voters were similar to their Russian Federation counterparts with respect to high levels of education and urban population. In a comparison of ethnicities, it also found that ethnic Russians were more likely to vote “against all” than ethnic Kyrgyz or Kyrgyzstani Uzbeks in Kyrgyz elections. However, as this study shows, characteristics like urbanity, higher education, and ethnicity cannot fully explain this voting behavior. In the case of Uzbek populations and districts, exposure to violence also plays a role.

An examination of votes at the lower, precinct level made it clear that the votes “against all” were further concentrated in a few parts of the country. By focusing on where this voting behavior manifested itself, this study was able show how the more intimate, recent political history of the southern districts of Suzak and Kara-Suu affected voting patterns. On a broader level, this study found that existing explanatory models (like the one used by Hutcheson to provide a profile of “against all voters”) are helpful, but can fall short of fully explaining protest voting behavior in Kyrgyzstan.

Works Cited

Alkan, Haluk. “Post-Soviet Politics in Kyrgyzstan: between Centralism and Localism?” Contemporary Politics 15.3 (2009): 355-75. Print.

Bergh, Johannes. “Protest Voting in Austria, Denmark, and Norway.” Scandinavian Political Studies 27.4 (2004): 367-89. Print.

Bohrer, Robert E., Alexander C. Pacek,, and Benjamin Radcliff. “Electoral Participation, Ideology, and Party Politics in Post-Communist Europe.” The Journal of Politics 62.04 (2000). 1161-1172. Print.

Bukharbayeva, Bagila. “The World; In Central Asia, Dreams of an Islamic State; The Discontent That Reverberates across a Valley Overlapping Former Soviet Republics Has Some Muslims Longing for a Better Life.” Los Angeles Times 12 Feb. 2006. Print.

Dalton, Russell J., and Christopher Anderson. “Electoral Support and Voter Turnout.” Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. 33-55. Print.

Electoral Moods of the Population of Ukraine. Rep. “Rating” Sociology Group, 11 Nov. 2011. Web. 16 Dec. 2011. Available online.

Guneev, Sergei. “Medvedev Urged to Restore Against All Option to Ballots | Russia.” RIA Novosti. 03 July 2011. Web. 16 Jan. 2012. Available online.

Hans, Oversloot, Joop Van Holteyn, and Ger P. Van Den Berg. “Against All: Exploring the Vote ‘Against All’ in the Russian Federation’s Electoral System.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 18.4 (2002): 31-50. Print.

Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper: The Andijan Massacre: One Year Later, Still No Justice. Rep. Human Rights Watch, 11 May 2006. Web. 17 Dec. 2011. Available online.

Huskey, Eugene. “The Rise of Contested Politics in Central Asia: Elections in Kyrgyzstan, 1989–90.” Europe-Asia Studies 47.5 (1995): 813-33. Print

Huskey, Eugene and Hill David. “Election Note: The 2010 Referendum and Parliamentary Elections in Kyrgyzstan.” Print.

Huskey, Eugene. “Kyrgyzstan: Electoral Manipulation in Central Asia.” Electoral System Design: the New International IDEA Handbook. Stockholm: International IDEA, 2005. 54-56. Print.

Hutcheson, Derek. “Disengaged or Disenchanted? The Vote “against all” in Post-communist Russia.” The Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 20.1 (2004): 98-121. Print.

“Kyrgyz Police Seize “Extremist” Literature in South.” BBC Monitoring International Reports 27 Mar. 2008. Print.

“Kyrgyz Report Calls for Joint Fight against Banned Islamic Group.” BBC Monitoring Report 14 Nov. 2006. Print.

Kostadinova, Tatiana. “Voter Turnout Dynamics in Post-Communist Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 42.6 (2003): 741-59. Print.

Le Vote Blanc. Vous êtes Sur Le Site De L’Association Pour La Reconnaissance Du Vote Blanc, Dec. 2011. Web. 16 Dec. 2011. www.vote-blanc.org.

Lijpart, A. Unequal Participation: Democracies’ unresolved dilemma, American Political Science Review 1997.

Lukashov, Ilya. “Spectre of Ethnic Violence in Kyrgyzstan – IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting – P34660.” IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting –. 19 May 2010. Web. 18 Dec. 2011. Available online

McAllister, Ian, and Stephen White. “Voting “against all” in Post-communist Russia.” Journal of Europe-Asia Studies 60.1 (2008): 67-87. Print.

News, Daniel Sandford BBC. “BBC News – Russia Election: OSCE Sees ‘Numerous Violations'” BBC – Homepage. 5 Dec. 2011. Web. 16 Jan. 2012. Available online.

Pacek, Alexander C., Grigore Pop-Eleches, and Joshua A. Tucker. “Disenchanted or Discerning: Voter Turnout in Post-Communist Countries.” The Journal of Politics 71.02 (2009): 473-91. Print.

Pop-Eleches, Grigore. “Throwing out the Bums: Protest Voting and Unorthodox Parties after Communism.” World Politics 62.02 (2010): 221-60. Print.

Powell, G. Bingham. “Citizen Preferences and Party Positions.” Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2000. 159-74. Print.

Radnitz, Scott. “Networks, Localism and Mobilization in Aksy, Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asian Survey42.4 (2005): 405-24. Print.

Sadyrkulov, Beksultan. “Renewed Unrest in South Kyrgyzstan – IWPR Institute for War & Dec. 2011. Available online.

Saparov, Jalil. “Kyrgyzstan: More Uzbeks May Be Sent Back – IWPR Peace Reporting –. 20 Nov. 2005. Web. 18 Dec. 2011.Available online.

Tucker, Joshua A. “The First Decade of Post-Communist Elections and Voting: What Have We Studied, and How Have We Studied It?” Annual Reviews: Political Science 5 (2002): 271-304. Annual Reviews. Atypon. Web. 27 Sept. 2011. http://www.annualreviews.org/

Tokbaeva, Dina. “Kyrgyz Parties Target Rural Voters – IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting – P220.” IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting –. 8 Sept. 2010. Web. 18 Dec. 2011. Available online.

“Uzbek Refugees Report Forced Return to Kyrgyzstan – IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting – P34661.” IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting –. 23 June 2010. Web. 18 Dec. 2011. Available online

“Uzbekistan Restores Border Control near Kara-suu.” The Times of Central Asia [Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan] 26 July 2005. Print.

White, Stephen. “Political Disengagement in Post-Communist Russia: a Qualitative Study.” Europe-Asia Studies 57.8 (2005): 1121-142. Print.

Footnotes

[1] For further reading on the role of personalities in post-Soviet elections and parties, see: Haluka Alkan (2009), Max Bader (2009), and John Ishiyama (2001).