For the past two months, the international community has been watching the Russian-Ukrainian border crisis unfold. The following article will try to gauge whether active conflict is likely.

As we shall see, under most scenarios, it is not.

Why Did Russia Annex Crimea?

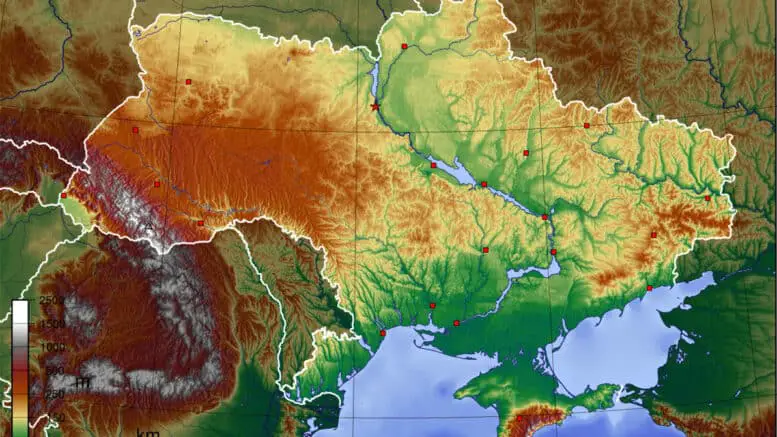

Topographical map of Crimea showing the Crimean Mountains – which rise straight from the sea to heights of around 5000 feet – and the peninsula’s thirteen-mile wide land connection with Ukraine.

It is true that Russia has absorbed Ukrainian territory in the recent past – with Crimea. This, for Russia, was a very high-value and relatively low-cost operation. Crimea had even (in 1994) voted in a regional president and parliament who supported Crimean ascension to Russia (in 1994) and still had a separatist movement that never really died. Russia annexed the land over the course of approximately five weeks, during which no battles were fought. Resistance to Russia’s presence on the peninsula has been, arguably, minimal since its takeover.

Meanwhile, Russia gained a large, permanent naval base for its Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol. Maintaining a strong naval presence in the Black Sea has long been a Russian national security imperative as, without it, the geographical advantage of the Caucasus Mountains protecting Russia’s southwest is largely nullified. Russia also gained five commercial ports at a time when its current ports were operating at capacity, limiting exports – particularly for its growing agricultural sector. It gained all of this on a highly defensible, large landmass protected by water and mountain ranges.

Why Wouldn’t Russia Want More of Ukraine?

At the same time that Russia gained Crimea, fighting also occurred in eastern Ukraine. With Russian support, the Donetsk People’s Republic (known as the DNR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) declared independence from Ukraine. Russia could have likely formally annexed these territories at the time, but did not.

The DNR and LNR offer no strategic ports and no naturally defensive borders. Russia has since absorbed much of the economic potential by encouraging emigration from the territories to Russia through eased citizenship requirements. The owners of several factories in these areas also relocated their production to Russia – and out of the increasingly war-torn area. The infrastructure that remains in these areas only continues to deteriorate.

As such, absorbing these areas would require billions in investment to restore their economic potential. It would also serve to push Russia’s borders closer to NATO member states, in direct opposition to Russia’s frequently stated goal of keeping NATO further away. Russia would not benefit from any naturally defensible border or other geographic advantage.

Some have hypothesized that Russia may want to push still more deeply into Ukraine, taking the ports in Mariupol and Odesa and creating a “land bridge” to Crimea. However, Russia’s multi-billion dollar Crimean bridge is now complete and greatly reduces the value of a land connection. Also, the violence that erupted in Odesa shortly after the events of 2014 shows that resistance to Russian occupation would be extremely high, adding still more to the cost of absorbing any new territory.

The value of supporting the DNR and LNR, to Russia, was the areas’ ability to be part of a disputed border. NATO has generally required that states resolve any territorial disputes before ascending to membership.

This is one reason why Russia has strongly supported South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia, where they have helped prevent Georgia’s NATO membership for years.

What Does the Russo-Georgian War Tell Us About Russia’s Strategy?

The similarities between the Russo-Georgian conflict of 2008 and today’s conflict on the Ukrainian border are striking. In 2008, Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili, feeling that he had Western assurances of support, sent a troop surge into South Ossetia to try to reclaim the de-facto independent region. Russia, however, was prepared for this with troops positioned on Russia’s border with South Ossetia and naval forces on the coast of Abkhazia (a second de-facto independent region internationally recognized as part of Georgia).

Russia immediately activated these forces to quickly push Georgia’s forces back. Russia advanced quickly, approaching Georgia’s capital, before unilaterally pulling back and doubling down on the status quo by formally recognizing the two regions’ independent statehood and encouraging its allies to also recognize them.

In this conflict, Russia did not seek territory for territory’s sake. It sought a status quo in which two regions that had won de-facto independence would maintain it, in which Georgia would be blocked from NATO membership without recognizing the independence of the regions, and, if it did, would only be able to join NATO with a greatly reduced and less strategic border with Russia.

What’s Different About the Ukrainian Border Crisis?

The Russo-Georgian War was quickly resolved in only eight days when Russia pulled back and declared victory. However, it was a war fought between one country with more than a million active duty troops (Russia) and another country with about 37,000 (Georgia).

Ukraine presents a much different situation, with about 280,000 active troops. Ukraine is also much better armed, with American missiles and military advisors and Turkish drones, for instance. America has also made a much greater show of support, moving American war ships into the area, securing promises from allies such as Germany that Russia would be punished if its military enters Ukrainian territory, and generally sounding a very loud alarm about the possibility of Russian intervention.

A Russo-Ukrainian war would not be fast or easy and both sides would suffer considerable casualties. This comes at a time when Russia’s public is largely against a renewed conflict. This serves to lower even further Russia’s potential incentives to start a war.

So Would Russia Invade?

There is one scenario in which I can see Russian troops crossing the border: the same scenario that started the Russo-Georgian War. If Ukraine decides to enact a military solution, perhaps as a “pre-emptive” move to counter a possible Russian invasion, Russia will, most likely, move to protect the regions’ de-facto independence as it has done in the past.

As with the Russo-Georgian conflict, I would not expect Russia to seek more than to protect the status quo. Any Ukrainian territorial losses would likely go to the LNR and DNR, whose independence would be formally recognized by Russia.

However, this scenario is obviously not optimal for anyone. Russia, Ukraine, and the people of the LNR and DNR would all suffer greatly for the likely outcome of a continued status quo. Western militaries would likely not be activated in support in Ukraine, as this would most certainly trigger a catastrophic and potentially nuclear WWIII.

Barring Western intervention, it is also unlikely that Ukraine would prevail in the conflict against what is, in the end, a much larger country – economically and militarily. At the same time, western countries would be hurt, if not economically from the decreased trade and increased energy prices, then by their images being tarnished as a state that they have vocally supported fights a painful battle largely alone.

In the end, it is in no country’s interest that any invasion occurs.

Isn’t There Another Way?

There are, of course, other routes that would be logically much better to take.

Russia and the DNR and LNR insist that nationally recognized local elections and the federalization of the regions’ status in the Ukrainian constitution should come first. Ukraine insists that the border with Russia should be secured by Ukrainian troops first and all Russian troops and mercenaries recalled. Ukraine insists that until this is done, no election can be considered fair. Russia, meanwhile, points out that if Ukraine were allowed to occupy the border, effectively surrounding the regions, that this would in effect be a military solution rather than a fair peace.

Implementing the Minsk Accords would therefore require a mix of troops allowed on the ground so as to give no party the upper hand while other measures are taken. This would require political will and careful planning, possibly through the UN, to both muster the forces and negotiate with Ukraine, Russia, and the rebel regions for the troops’ acceptance and peaceful implementation.

Other, more extreme but still non-violent resolutions could also be taken. Ukrainian recognition of the republics would be painful, especially to the political capital of Ukrainian politicians, but it would allow Ukraine to pursue NATO membership and, likely, leave Russia with greater responsibility than Ukraine to financially support the republics.

How Likely is a Conflict?

Simply having troops and equipment near a border does not mean that invasion is imminent. The US, for instance, has kept tens of thousands of troops near North Korea as both a negotiating tool and as a precautionary measure, should they be needed. Yet the US has not invaded North Korea.

Modern technology is also helping to keep the peace world wide because it is increasingly difficult to over- or underestimate an adversary’s forces. With satellite technology, the growth of bases and movement of troops can be much more reliably tracked. With this, any troop buildup can be much more precisely countered (such with Ukraine’s matching military buildup on the other side of the borders of the LNR and DNR). This helps ensure that it is increasingly difficult to “bluff” a military force and increasingly easy to know exactly how many troops to move to the other side of a standoff to maintain a relative balance. Indeed, Ukraine has currently responded to reports of about 100,000 Russian troops by deploying about 100,000 Ukrainian troops to its border.

The current posturing by Russia, the US, and their allies is part of other political issues – such as Russia’s opposition to NATO expansion and the US opposition to the Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. As all parties look to de-escalate the situation, these issues will likely be considered and perhaps advanced. Talks are currently talks set to begin for January 10 between the US and Russia to discuss the various issues at hand. These will continue afterwards for sometime in various formats.

If all parties remain logical and do not succumb to their own elevated rhetoric an active conflict is unlikely.