Despite its distance from the hotbed of Russian revolutionary violence, the city of Vladivostok and the Russian Far East experienced their own challenges and intrigue in the seldom recalled Allied intervention in Siberia, spanning from 1918 to 1925.

The Treaty of Brest Litovsk, signed by the infant Bolshevik government in Russia and the Central Powers, officially silenced the Great War’s eastern front. For Germany, this created the option of mobilizing it’s armies to the western front, which caused the Allies much consternation. Throughout the war, the Allies had supplied war materiel to Tsarist Russia to help keep the Central Powers split between two fronts. Because the traditional trade routes were cut off, all supplies came through Murmansk and Arkhangelsk in the north and Vladivostok in the Far East. All shipping going to Russia through Vladivostok was due to be transferred west via the Trans-Siberian Railway. After the revolution began and the Bolsheviks signed Brest Litovsk, the armament and munition transfers from east to west stopped. With over one billion dollars’ worth of guns, ammunition, and medical supplies stranded on Vladivostok’s docks or at depots along the railroad, the Allies began to fear that it might fall to Bolshevik or even German-influenced factions in the politically fragmented nation. They had precedent to create an expeditionary force for intervention in the east, but what cemented the resolution to intervene was the Czech Legion.

The Czech Legion was a battle-hardened force of more than 50,000 ethnic Czechs who had fought alongside the Russians prior to Brest Litovsk. After the treaty, they began to move east with the hope of escape but became stranded and caught in the middle of the civil war. The Allies planned to extract these troops so they could eventually serve in France. The safest route out of Russia happened to be east, travelling along the Trans-Siberian Railway.

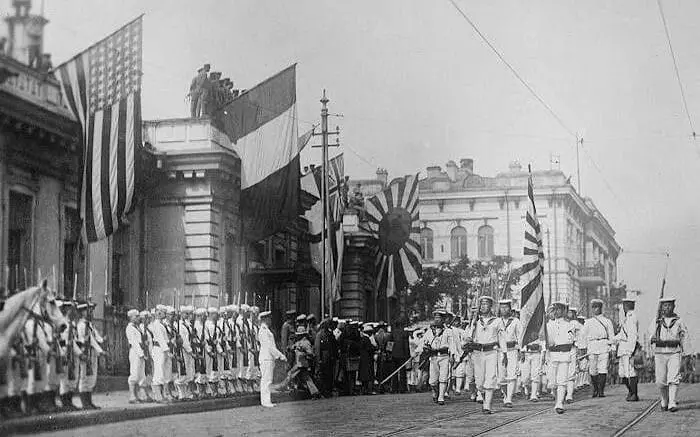

Japanese, American, British, French, Canadian, and Italian forces all landed in Vladivostok over the course of 1918 with the intent of holding key cities throughout Siberia, maintaining order, and especially defending the railway that provided the only link to the west.

Japan had its own designs for Siberia and the Amur basin. Seizing upon the upheaval within the Russian government and with the pretext of joining in the allied intervention, Japan sent a naval contingent to Vladivostok early in 1918. In April, after a Japanese sailor was murdered in the city, Japan gained further impetus to send troops to the region, “to protect its citizens” there. The Russian Council of National Commissaries condemned the buildup of forces and questioned Japan’s motives, even going so far as to say that the murder was orchestrated. Japan steadily added to its expeditionary force until it reached a total of approximately 70,000 soldiers, making it by far the largest foreign intervention force in Russia at the time.

In August 1918, the United States landed its first troops in Vladivostok under the command of General William S. Graves. American President Woodrow Wilson stated in a letter to General Graves that the purpose of the expedition was threefold:

1. Render aid to the stranded Czech legion

2. Protect military supplies previously used in the war effort

3. Provide humanitarian assistance to the Russian people.

With the growing power of the Red Army, evidence also suggests American involvement was meant to support the White Russians in the civil war. Over the coming months, American involvement grew to a total of approximately 10,000 soldiers. Records from the War Department show that much of the time spent in Siberia was spent encamped, drilling and training, although the US force was in charge of defending and servicing sections of the railway as well as performing police duties in Vladivostok during their eight month stint in Russia.

The Russian armies in Siberia during the Revolutionary period primarily fell under the leadership of two individuals. One, Admiral Alexander Kolchak, a White Russian leader, chose to cooperate with the Allies to suppress the Bolshevik advances into Siberia. He was successful for a time in asserting regional control in the Russian Far East.

The other Russian leader was Grigorii Semenov, head of a deadly band of Cossacks who fell under no one’s authority. Although Semenov occasionally worked alongside the Czech Legion and Admiral Kolchak’s forces, his Cossacks were undisciplined, and became famous for terrorizing routes along the railway, raping and stealing wherever they went.

After the Central Powers capitulated to the Allies in November of 1918, the multinational expeditionary forces suddenly lost their reason for intervention. They had to change course, and they settled on supporting the White Russians in the civil war.

By the time the Czech Legion finished evacuating Russia safely in January of 1920, all of the Allied intervention forces had already departed or would leave in short order, except for Japan. Japan’s imperial ambitions, coupled with the fact that the civil war was far from finished in Siberia meant that they would leave their troops throughout the region to ensure protection of Japanese residents and ideally establish ownership of a new Japanese province (although this was never the official statement). A massacre of Japanese residents on March 15, 1920 in Siberia gave Japan the diplomatic pretext it needed to keep its troops stationed in Vladivostok, as well as other strategic locations in the region. As the months passed, it appeared that Japan had no intention of leaving.

For the next five years, Japan retained its hold on eastern Siberia. Only after steadily increasing diplomatic pressure from the United States and later Great Britain, along with the growing Russian resentment of occupation, did Japan pull its last soldiers out of Russia in January, 1925.

After seven years, the Allied intervention in Russia finally came to an end.