The National Library of Russia has multiple locations in St. Petersburg.

How to Sign Up

Library cards can be attained at the Registration Desks either on the ground floor of the Main Building on Nevsky, the new Building on Moskovskaya, or the Fontanka Embankment building. They’re open 9-21 Monday-Friday, and 11-19 Saturday and Sunday.

Bring your passport with visa, migration card, and either proof of a completed degree from an institute of higher education (diploma), or a valid student card with the level of course studied/studying. They need to see original documents; no copies are accepted. Photographs are taken there for the library card, so no need to bring your own. For foreign visitors, the library cards are only issued for the duration of the current visa, and must be renewed every year. Besides the usual name, birth date, address, and university, here are more specifics to consider on the application.

Фамилия, Имя, Отчество // Surname, Name, Patronymic

Дата рождения // Birth date

Паспорт (серия, номер) // Passport number

*Образование, ученая степень // Education, specific degree

Специальность// Specialty or major, usually the faculty name is fine

**Место работы, учебы // Place of work or studies.

Гражданство // Citizenship

Адрес // Address

Телефон// Telephone

E-mail address

* They’re asking for your completed degrees, so if you’re still an undergrad, write полное высшее for your completed high school diploma. And because I didn’t bring my diploma, I copied what was on the template they gave: диплом не предъявлен, согласна(о) на «О» на срок действия 4/Ъ.

** For the place of study, besides the university name itself, include what course (year) you’re in and if it’s the bachelors (бакалавра) or masters (магистра) program.

Hours and Locations:

The entrance to the Main Library is in Ostrovsky Square, 1/3, off of Nevsky Prospect.

The Krylov House is in the same complex as the Main Library, but its entrance is Sadovaya Ulitsa, 20.

The New Building is across from Park Pobedy on Moskovsky Prospect, 165/2.

The Building on the Fontanka Embankment is located at number 36.

The Building on Liteyny Prospect is located at number 49.

The Plekhanov House is on 4th Krasnoarmeyskaya St, number 1/33 near the Tekhnologicheskiy Institute metro station.

Each building and areas within have different hours, so better check this for your specific location.

Available services at the National Library:

Interlibrary Loan, digital or hard copy

The Center for Recovered Names in Information Services holds a database of those sent to the gulags in the northwest region of Russia during the Soviet era. The library also published the “Book of Memory,” the Leningrad Martyrology (five volumes) concerning those considered enemies of the state who were executed in Leningrad and the Leningrad region. Their Annotated Index to the Book of Memory of the Victims of Political Repression in the USSR is available as a digital copy on their website.

The Legislative Center provides public access and assistance to legal information. For a fee, they will allow saving or sending the data you found, access to a database of dissertations, and some trainings.

Reading rooms check the site for specific opening and closing times.

Main building: general, foreign books, Russian books, Russian periodicals, maps, manuscripts, prints, rare books, library science, computer center

Krylov House: information service, bookshop

New building: social sciences & economics, humanities & art, medicine & biology, science & technology, foreign books, Russian books, Russian periodicals, foreign periodicals, national literatures, microforms, standards & specifications, non-literary collections, computer center

Fontanka Embankment: newspapers, printed music & recorded sound, juniors (kids and young adult), listening & viewing service

Liteyny Prospect: Asian & African collection

Plekhanov house: Manuscript sector

Also, the National Library offers guided tours, allows photographs of the interior, and visitors can request a tour for certain department if they have a specific interest.

History of the Library with Notable Directors

Known as the Imperial Public Library between 1814-1917, it was the first national library in Russia. Catherine the Great approved the establishment in 1795, and who herself owned the domestic libraries of Voltaire and Diderot. The Main Building was designed by Yegor Sokolov on the corner of Nevsky and Sadovaya, and took almost 15 years to complete. It was to open to the public in 1812, but the inauguration was delayed for two years due to Napoleon’s invasion. The grand opening was held January 14, 1814, and was a great source of pride for the Piter residents regardless of nobility or profession.

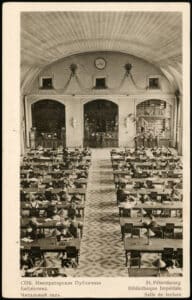

One of the reading rooms in the Imperial Public Library in the early 1900’s. Check out the Churakov Collection online on the library’s website! Follow the link in the article or click the image.

The third director, Aleksey Olenin, maintained the society’s regard for the library through the Russian Enlightenment. He regularly held a salon with leading Russian intellectuals and elevating the library itself as the pinnacle of enlightenment in the 19th century.

During Olenin’s time, Count Alexander Stroganov initiated the Rossika project: a massive collection of books about Russia written by foreigners or Russians living abroad. Vasilii Sopikov headed this project, who was known for his Essay on Russian Bibliography which registered printed works in Russian and Church Slavonic published in Russia and abroad from early Slavic prints up to the early 19th century.

The director from 1849-1861, Count Modest von Korff, is credited with the gigantic administrative feat of organizing the library and holding a public auction for duplicates amassed over the years. Meanwhile, the head of Russian department Afansi Bychkov and assistant Vladimir Mazhov appealed the censors’ office to initiate a law stipulating a copy of every new publication for the library. Due to their efforts, around 90% of everything that had been published in the Russian language was accounted for in the library by 1864. The mid-19th century was the highlight of societal generosity and eminence for the library. The National Library received almost thirty times more monetary and literary donations in one decade than the first half of the 19th century combined. Attendance of regular users and library card distribution remained at record highs until the turn of the century.

Following the February Revolution of 1917, the library became simply the Public Library of Russia under an executive council appointed by the Provisional Government. A notable concession was to allow women to be employed as official staff as opposed to the voluntary status they held since the late 1880’s. The Public Library closed for a few days after the October Revolution, and the People’s Commissariat for Education approved a new set of statues similar to the decrees of the preceding Provisional Government. The supplements included more council responsibilities and increased sense of expectation of the library to provide assistance and resources to the general public.

After the First World War, the revolutions, and the Civil War, the number of library users fell to around a tenth of the total of pre-war patrons. While acquisition from abroad and new supplies declined, the Public Library integrated the libraries of individuals, public organizations, cathedrals and monasteries, and other governmental departments such as the State Council, the State Duma, and the Ministry of Justice. To deal with the influx and stress on the main library’s reading rooms, these collections were largely designated as branches of the Public Library in areas like the Shuvalov Mansion on Fontanka and the Taurida Palace. Many of the branches were closed in 1946, although the Plekhanov House remains as a part of the National Library today,

The State Public Library created the Special Storage Department beginning in the mid-1920s as a result of decreased access to State-sanctioned forbidden works, with the majority originating from 1935-1938. The old edict requiring a library copy of all publications resumed in the mid-1930s, while most of the other acquisitions were predominantly themed technology and economics. The present-day distinction between ‘general’ and ‘research’ reading rooms arose at this time in history.

The library remained open during the siege of Leningrad although almost three quarters of the workforce died during the siege. The most valuable collections were packed off to the Ulyanovsk region and were returned in October 1945. The Public Library greatly contributed to the war effort in Leningrad – it hosted some of the city’s ill in an infirmary constructed in the library and over 42,500 people made use of the library. The military also used the library for information on how to construct defenses and roads over frozen bodies of water, field surgery, and other considerations.

And Finally!

After the war, the library’s collections, buildings, and patrons steadily grew. The additional building on Moskovsky Prospekt began in the late 1980s. The Lenin Library in Moscow was previously the national book repository for the Soviet Union, but after the break up of the USSR, President Yelstin transferred the role to the Public Library. Afterward, the library was again recognized as it remains known: the National Library of Russia, the oldest public library in the nation. It’s ranked among the world’s major libraries, and holds the second richest library collection in the Russian Federation. And it is, as it’s always been, free to the public.