In recent months political disputes between Russia and the United States have grown to

America’s Continued BMD Expansion

Russia’s stepped up criticism of U.S. intentions to build a missile defense system with North Atlantic Treaty Organization members is likely a belated response to Washington’s 2002 unilateral withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty – a move that at the time evoked little commentary from the still-greatly-weakened Russia. After the treaty’s abrogation, America’s Missile Defense Agency (MDA) launched (or accelerated) a number of multi-billion dollar projects – everything from ground- and sea-, to forward-based lasers and missiles – to create a networked BMD system for the United States.

Now, to protect allies and forces deployed overseas, the U.S. government has decided to expand its BMD coverage to Europe – even as work has progressed on new domestic missile sites in California and Alaska, aboard Aegis-equipped destroyers in the Pacific Ocean and on a 28-story floating radar station known as the SBX. Now, also under consideration is a proposed emplacement of 10 long-range, ground-based missile defense interceptors in Poland, as well as a mid-course radar in the Czech Republic.

The U.S. BMD expansion plans are pushing forward. The Czech government gave its assent to placing a missile defense radar near Misov, 50 miles southwest of Prague on July 3. The Czech Parliament will need to give its final say on such a deployment, but Warsaw’s Deputy Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski expects a deal to be reached sometime in the fall. Great Britain also agreed in July to allow expanded facilities at Menwith Hill, a U.S operated military base in England, to provide early warning information for America’s BMD system.

Russia’s Start to BMD Recovery

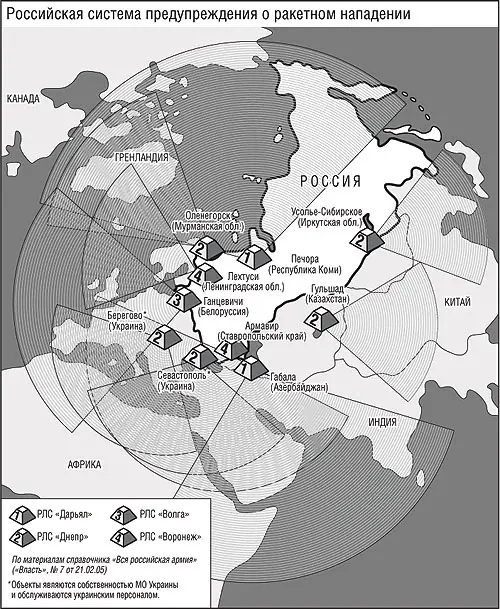

In contrast to America’s expansion, Moscow’s air and missile defense systems have lost significant overseas assets in recent years. The breakup of the Soviet Union curtailed the Kremlin’s access to numerous BMD ground sites, many of which landed in newly independent nations. In any case, insufficient resources were available for the support and maintenance of the system and many sites simply went offline. In particular, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact created significant problems for Russian early warning and radar coverage of NATO member states – a growing concern as those forces moved closer to the Russian homeland with every enlargement phase.

In particular, Russia lost its Daryal-UM radar based in Skrunda, Latvia in May of 1995. The Dnestr-M radar, also in Skrunda, ceased operation in 1998. This posed “a loss of important monitoring parameters,” according to Col. Gen. Vladimir Yakovlev, commander-in-chief of the Russian strategic rocket forces.

Ukraine also hosted several radar stations on the former Soviet periphery. In Mukachevo, near the Slovakian border, a Dnepr-M radar station entered service in 1979. A second Dnepr radar system entered service in Sevastopol on the Black Sea that same year. The post-Cold War Russian air defense forces have continued to rely upon these sites for aerial coverage but shaky relations between Ukraine and Russia have meant that the transmission of data, forwarded by Ukrainians, has never been completely satisfactory for the Russians. Moscow currently pays 1.3 – 1.5 million USD to rent these sites from Ukraine.

Should Moscow lose all access to the sites, Russia would suffer a drastic decline in airspace coverage over southwest Europe and the Mediterranean Sea. Strategic warning systems would also be affected by this potential further reduction in Russia’s airspace perimeter, according to former Russian space and missile defense commander Col. Gen. Volter Kraskovski. Even so, the post-Soviet agreements that have allowed Russian forces to continue accessing Kiev’s radar coverage never pointed the way toward permanent cooperation.

Hence, Moscow has now prepared to invest in new BMD sites on its own territory. In December 2006, Moscow activated a new Voronezh radar system at Lekhtusi, a space operations training base located not far from St. Petersburg, ending a potentially dangerous seven-year gap in coverage over northern Russia and the arctic that resulted following the 1998 closure at the Skrunda facility in Latvia. A second Voronezh radar at Armavir, located in the Caucus Mountains of Rusia, conducted initial operations at the end of 2006 and is scheduled to enter service in late 2007, mitigating the potential loss or eventual obsolescence of the Gabala site in Azerbaijan.

The loss of control over Soviet-era installations forced Moscow to prepare an air defense with a shrunken perimeter. In Ukraine and Latvia, where the political winds blew West, Moscow sought to buy time by essentially leasing facilities, while it developed and built new radar stations on its own soil. Leaders signed temporary agreements that allowed Moscow to continue accessing surveillance data provided by former Soviet monitoring facilities. Despite these measures, with the dearth of resources that occurred in the 1990s and the loss of several stations, gaps in coverage – west from Latvia over the northern Atlantic Ocean and perhaps south into parts of the volatile Middle East – occurred.

In countries with greater allegiance and ties to Moscow, the Kremlin has been able to keep a firmer grip on its Soviet-era integrated radar system. The Baranovichi and Balkhash (in Belarus and Kazakhstan, respectively) sites have not yet proven themselves bones of contention as have facilities in other former republics.

Figure 1. A map showing Russia’s early warning system. Map developed from material in Vlast, Issue 7, from 02/21/05. No English version currently available. Note that while the Armavir radar appears here in the Stavropol Krai, it is actually located in the nearby Krasnodar Krai.

The Future of Russian and US BMD Systems

In the long-term, the loss of older assets located abroad – replaced by more modern sites inside Russia – will improve the Russian military’s ability to monitor and defend its airspace. A shortened air defense perimeter will require fewer radar installations to provide adequate surveillance and early warning coverage against aircraft or missile threats to Russia.

Russia’s recovering BMD capabilities are also leading to a renewed ability to cooperate with, or confront, the West. Many fear that Putin’s recent suggestion to integrate Gabala or another new Russian radar site, into the U.S. missile defense network may be a political ruse.

Yet, at a time when relations between Washington and Moscow are frosty regarding many issues, cooperation on BMD – as pointed out by Henry Kissinger in a recent Washington Post opinion piece – could accomplish several important goals. It would reassure U.S. allies that Washington can engage states diplomatically on a multilateral basis. BMD integration could also help cement a broad front for opposing nuclear weapons development in Iran and other rogue states by combining two of the world’s largest BMD systems.

From Moscow’s perspective, BMD cooperation could improve Russian air defense force capabilities. Most importantly, Russia would gain reassurance that a European defense shield is not an offensive weapon aimed at Russia and claim prestige attached to missile defense cooperation with the current leader in that field, the United States.

Editor’s note: There has been much coverage in the Western media about the current US-Russia disagreement over ballistic missile coverage. However, most stories have focused on emphasizing the more dramatic events rather than attempting to provide their readership with an understanding of the issue at hand. Hence, Putin’s comment that Russia would direct missiles at America’s system in Europe (which, from a military point of view, is an understandable and perhaps even necessary step for Russia), but little of the history of the events, which includes America’s unilateral withdrawal from an Arms Reduction Treaty, has been given air. We are therefore pleased and honored to publish this informative and impartial article.