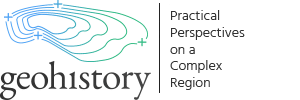

The picture of “Comrade Lenin Sweeps the World Clean of Filth” (below) is a perfect illustration of Soviets’ axiological orientations: they felt a moral duty to get rid of the “rotten bourgeoisie” in order to create a “brand new world” whose main values are fraternity and egality. The grotesque caricature, however, is interesting not because of a rupture between what was said and what was done, which has already been examined multiple times in all of its nuances in other papers. This study will focus on the visual and verbal code utilized in conveying this message of the need to cleanse. Here, Vladimir Lenin is depicted as a careful janitor sweeping away monarchs, clerics, and the gluttonous wealthy class. The latter are called “filth, the impure,” which is a figurative way of expressing the immorality of these social groups. Such a discursive transition, linking a physical phenomenon (dirt) with moral qualities, is a distinctive feature of Soviet authorities’ discourse, and the picture acts as an icon of the reconfiguration of the discursive order that started with the Russian Revolution and was continued by Stalin.

A Need for a Brand New World

Image 1. “Comrade Lenin Sweeps the World Clean of Filth” (1920), source: online

Another illustrative example of this is Korney Chukovsky’s 1938 children’s poem about a creature Moydodyr, (Мойдодыр), whose name translates to “Wash ‘til Holes.” Moydodyr takes care of dirty children. A line from the poem: “If you’re an unclean Chimneysweep – // Shame and disgrace! // Shame and disgrace!”[1] became a popular expression used to encourage youngsters to cherish hygiene and maintain cleanliness.[2] It would be naïve to state that these lines from the poem are merely pedagogical: as a matter of fact, appealing to a child in such a manner is a technique of subjectivation; it uses verbal intimidation, focuses on exclusion and, in so doing, constructs an obedient subject, a docile body “as object and target of power.[3]” Moydodyr, a washstand, surprisingly resembling Stalin himself with dark bushy eyebrows and wide chest, is a figure that represents both physical and moral control, a metaphor of Stalin’s Cultural Revolution. Even the name of the protagonist, Wash ‘til Holes, could be perceived as a stylized representation of the cultural policy in the USSR under Stalin: to clean the unnecessary layer of values and beliefs that are “filthy” until holes in subjectivity appear – and fill them with “clean” ideological prostheses, in other words, to destroy a subject and construct a new one.

This paper attempts to demonstrate that the discourse of personal care, which took the form of propaganda, was not purely medical but intertwined with multiple other discourses, utilized to construct a certain subjectivity of citizens of the USSR under Stalin in the 1930s. It is not, however, stated that improvements that took place in the domain of public health were introduced as a means of political control and did not have any positive outcomes,[4] but neither is it justified to say that the authorities did not take advantage of the additional opportunity for ideological indoctrination in implementing these improvements.

This paper will examine the role that visual propaganda played in this discourse. The visual propaganda considered will be specifically posters, which, as a genre, are vivid, concise and appealing to the public. These posters are considered the most illustrative examples of subjectivation techniques used by the authorities, as well as the Stalinist authorities’ ability to mix discourses to achieve ideological goals. The title of this paper – “Healthy Body, Healthy Mind” – is drawn from the Roman poet Juvenal. The original wording of the quote is: “You should pray for a healthy mind in a healthy body.” This phrase was altered by communists, so the prayer was discursively transformed into an imperative, and precisely such concealed ideological imperatives are symptoms that are of particular interest – not because they are helpful in terms of reconstructing the discourse, but because they allow us to deconstruct it and show its strong dependence on the needs of the totalitarian state.

The Macro/micro Paradox of Totalitarianism

To establish a frame for further analysis, a paradox inherent to totalitarianism has to be resolved. Totalitarianism, in layman’s terms, is a political regime in which the government strives to control every aspect of the individual’s life. The paradox becomes evident if two dimensions, macro and micro, are introduced: there is a negative correlation between a macrodimension, or width, and a microdimension, or depth. In other words, if a government seeks to gain control over all spheres of citizens’ lives, it would be highly problematic to control them in depth, and vice versa; as resources (whether material or immaterial) are always limited, there is a possibility of thorough and all-encompassing control only of a tiny number of spheres. This inevitable disequilibrium is described by Economist Mark Harrison as “a world of agonizing dilemmas[5]”, because a leader always has to make decisions about how to keep balance between the regime’s and the people’s needs (or, in other words, to achieve a situation in which they both maximally coincide).

Thereby, the paradox is fortified as a second opposition is introduced: power and resistance. As Foucault explains, “a relation of power is a relationship between someone who is looking to dominate or is dominating […] and somebody else […] in a situation of being dominated, of refusing this domination, to flee from domination, to do battle with it[6].” Thus, power is never static; it is dynamic. Where there is power, there is always opportunity for resistance. Hannah Arendt states that there are two tools utilized by totalitarian governments to combine macro and micro, to strengthen their power positions and, consequently, eliminate any counteraction: terror and propaganda. As she explains, “propaganda (…) is one, and possibly the most important instrument of totalitarianism for dealing with the nontotalitarian world; terror, on the contrary, is the very essence of its form of government.”[7]

While terror in a most abstract sense was “the very essence” of the Stalinist state, it is difficult to argue that Stalin’s aims were merely negative and destructive and the nation was kept in a state of constant fear. In fact, the political project of Stalinism consists in the construction of socialism as a positive order. Stalinism, as the scholar Sergei Prozorov explains, may be distinguished from the earlier periods in the history of Bolshevism precisely by “its emphasis on the productivity of power in social reality.”[8] Destructivity and the negation of the past order were inseparable parts of Stalinism. However, these aspects were concealed and presented in the largely positive ideologeme of “The New Soviet Man,” which was a kernel of the ideology of Stalin’s cultural revolution. Historian David Hoffman argues that

“in their attempt to create the New Person, Soviet authorities relied on control of the living environment, education, and inculcation of the practice of working on oneself. It was their belief in the plasticity of humankind that heightened their ambition to transform not only people’s daily habits and culture but their modes of thinking and human qualities as well.”[9]

The Stalinist “Great Break” in the politics of Soviet Union could be defined as a shift toward biopolitics: “the growing inclusion of man’s natural life in the mechanisms and calculations of power.”[10] As demonstrated by Prozorov, Stalin’s tropology of the Break, the Cultural Revolution, and the New Man represents “the presupposition of the violent forcing of something new into a domain radically heterogeneous to it and the forcing out of all that conflicts with the newly produced reality […] Soviet biopolitics was from the very beginning hostile to the very life it sought to govern.”[11] This is because the revolutionary ideologeme “The New Man” presupposes that there is the Old Man, a type of subjectivity that must be not just reconstructed, but destroyed and constructed anew; The New Man is the only subject that could live in an established communist society. The target of Stalinism was a new, fully constructed form of life, in which the biological basis is constantly negated by the subject who seeks to gain absolute control over the environment and his/her own nature.

Ultimately, such a political orientation required a new policy. Omnipresent and omnipotent terror, described by Arendt, was doomed to fail because, again, its essence is destructive, not productive. Constant destruction will eventually result in complete destruction, including destruction of the destroyer. It bears repeating that the stated purpose of Stalinist socialism was to build anew.

What was needed was a set of instruments allowing the authorities to transplant the common ideological macroelements into microcontexts, and from this perspective Foucault’s notion of “microphysics of power” could shed light on the totalitarian administration of people’s lives. The microphysics of power can create docile bodies through the unconscious reproduction of certain actions (discipline), rather than through terror and intimidation. Thus, the microphysics of power (combined with macrophysics, that is, an all-embracing control) made “the integration of a temporary, unitary, continuous, cumulative dimension in the exercise of controls and the practice of domination[12]” possible. Although terror remained, the center of power shifted toward propaganda, from intimidation to repetition; the power itself disseminated, so everyday practices were charged with it: for example, the creation and consumption of education and art became controlled by the state, and citizens were pushed to become active in approved social activities – including youth, political, and sports associations. Even eating in canteens, an effort to control the rituals of food preparation and consumption, was encouraged. Intimate spheres like hygiene and personal health were no exception.

Therefore, in an attempt to uncover the biopolitical foundations of the discourse of hygiene and personal health, a critical look, aimed at identifying the ideological echoes in the visual statements, should be applied. Bearing in mind that every public-oriented statement was not just a dictum, but a dictum in order to, the analysis will focus on how the conflict of the structure, the state, and the agency, the addressee, is resolved and what characteristics of “The New Man” are ciphered in posters.

Finally, the concept of “subject” (as The New Man was a subjectivity desired by the Soviet authorities) needs a brief explanation; the subject is understood not in a traditional sense as an autonomous personality but rather as an individual who has to be subjectified, and which has to become a subject (using Althusser’s term, an interpellation[13] has to take place). Once again, this becoming is always invested with power. According to Foucault, the subject as locus vacuus, an initially empty space, emerges on the discursive surface as a point of the intersection of dispersed discourses.[14] Hence, it is not stated that the techniques of the subjectification of the New Man used in the Soviet visual propaganda of personal care are unique. In fact, many of these techniques seem rather familiar and can be found, for instance, in contemporary advertising, since they are techniques of power in general.[15] What makes the Soviet visual propaganda specific, however, is its depiction of the subject qua the sum of different discursive elements, the subject as an assemblage, the many traces of the discourses of power that formed the New Man through the propaganda of personal care.

Bringing Up the Younger Generation [16]

It was Lenin who first proclaimed that, “The private life is dead”. Stalin’s aim was not so radical: in fact, he attempted to blur the border between “private” and “political.”[17] However, people were not supposed to sacrifice their lives in the name of a permanent revolution. Rather, their lives were supposed to gradually become transparent or at least easily controllable by the government, as shown by Hellbeck.[18] This aim could have been achieved by eliminating any element of unexpectedness and by turning former peasants into “new” men and women. There was an imperative of “becoming cultured – though not in the domain of the state politics, but in the sphere of everyday life.”[19] Yet the concept of being “cultured”, due to its vagueness, was a perfect tool for the authorities, and it came to essentially mean be obedient and do what you are ordered. Thus, it comes as no surprise that it was “impossible to call a person cultured, if s/he doesn’t keep his/her body clean[20]” – because the body as an individually controlled thing was the last bastion of private life that Soviet authorities sought to destroy.

The discourse of public health was occupied by the government, as Foucault linked a nuclear family with a new type of medical rationality (for example, parents had to be not merely a mother and a father but at the same time “diagnosticians, therapists and agents of health,”[21] because they were the closest to their child’s body). It may seem quite natural to take care of one’s children, yet it is important to emphasize that this officially endorsed rationality makes a body the object of the semiotechniques of control, which can be intensified later. This was a distinctive feature of life for Soviet citizens from an early age. Certainly, they were controlled both vertically (for instance, children by their parents) as well as horizontally (by peers, fellows, and colleagues), but the ideal to be reached was a full self-governance, utilizing state-approved sensibilities, of one’s hygiene and health.

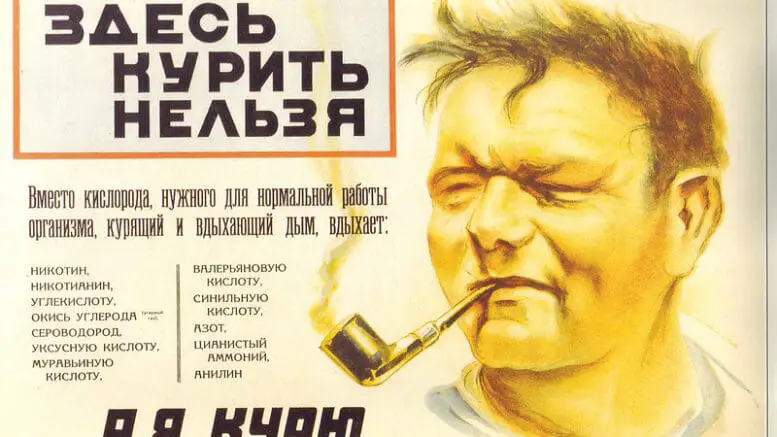

Image 2. Soviet adverisement (1930s), Source: online

This poster, seemingly innocent and resembling advertising posters today, is an illustration of the authorities’ attempt to gain at least discursive control over children’s bodies by the inculcation of everyday practices. The addressee is the school-age child who “knows this phrase by heart: having woken up in the morning – a toothbrush and also a dental powder.” It is peculiar, however, that this deceptively innocent phrase is worded in the form of a command, a rigid procedure that every pupil must follow. It is different from contemporary visual advertising in that it relies on a detailed description of routine procedure. The key imperative is not “to buy” but rather “to do.” This illustration targets more intimate spheres than the shopping cart or pocketbook: namely, the home and body. What is more, there is a discursive border that separates pupils who know what they must do by heart (that is, good qua obedient) from implied pupils who do not know or do not do what is ordered; the latter are inferior, wrong, defective, and thus (as it could be implied) have to be “fixed.” “To fix” was a common strategy to combat insubordination, and it was extensively applied to so-called social parasites, as a preventative measure before they became enemies of the state. Therefore, there is a hidden parallel with such parasites, known widely as tuneyadtsy(тунеядцы), who were considered antisocial not only in terms of their activities, but in terms of their way of life and personal care.[22]

The subjectivation of a younger generation was especially important for the authorities, presumably because they were “the cleanest,” or to be precise, a tabula rasa, the most suitable as an object of ideological inculcation[23]. This subjectivation had two forms: a) as demonstrated above, the authorities’ messages oriented toward children; and b) the use of a figure of a child as the author of social messages. Considering the fact that Stalin’s Cultural Revolution was biopolitical, the second use is explicable by an imperative to care, mainly about children as vulnerable subjects and part of a healthy population, which was synecdochically represented by children in posters.

The figurative role of youngsters was ambivalent: on the one hand, they were normally depicted as immature and easily affected (thus it was a moral duty to set a good example for them); on the other, hierarchically, children were still inferior to adults, so being taught by a child implicitly meant falling behind, failure to be a model citizen (and a requirement to take actions to make up for it).

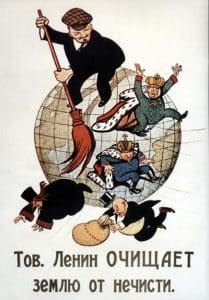

Image 3. “Our ultimatum to adults” (1930), source: online

In the poster, “Our ultimatum to adults,” the described technique is applied. Highly emotionally charged phrases such as “do not poison the air,” “do not set a bad example,” and “you lose our respect,” as well as the faces of crying children, construct the practice of smoking not only as unhealthy but as immoral. This ideologized depiction of decent pioneers is not accidental: one of Stalin’s guidelines of The Great Break was industrialization, and the Stakhanovite movement, as a movement of committed and extremely productive workers, was one of the pillars of this policy.[24]

Both the Stakhanovites and the Young Pioneers were founded to maximize productivity. As Suny explains, “factory workers […] wasted hours each day, loitering and taking smoking breaks.”[25] The regime needed docile bodies not only in a political, but also in an economic domain (mainly because the state was in a deteriorating economic condition). Hence, demonizing smoking by linking it with moral corruption and negative impact on children was one more ideological move to reach the state of totalization and effectively use a worker in his/her workplace, making him/her a subject of discipline.

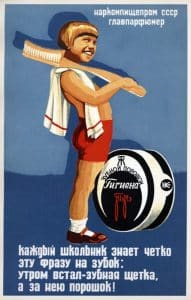

Image 4. Soviet social advertisement (1929), source: online

Another example is the poster, “Spirit (alcohol)/sport,” depicting a pioneer boy and a phrase “With ‘o’ – power, with ‘i’ – a grave.” Two crucial semes for the Stalinist regime, power and death, are at the heart of the interplay, which could be rewritten as: “So long as you are obedient, you are on the side of power, otherwise you are dead.” The figure of the pioneer serves as a perfect example of an ideologically constructed subject and reinforces the message. “Alcohol/sport” is an illustration of Stalinist biopolitics at its best, as biopolitics, or the politics of deciding how an organism should live, inevitably has its dark side. In this case, that dark side would be thanatopolitics, or the politics of deciding which organisms should live and which die.[26] The role of a sovereign is to decide who is granted life and who, on the contrary, must die (though in contemporary biopolitics this opposition is not so fixed, and there could also be decisions on who must live and who must not die). The latter juxtaposition is also present in the poster: the New Man can only better him/herself (by exercising, that is, s/he is forced to maximize his/her life energy), while the decision to harm one’s own health is presented as a straight path toward death (the decision that is reserved by the government).

Strong Body, Strong State

The target of “culturization” was not only the younger generation or inefficient workers, but all citizens in general (and as a whole). As Volkov explains, the “culturization” model was an alternative to Stalin’s “Great Terror,” a positive strategy of power.[27] Yet the concept was never specified, and none of the representatives of the party of the government could give a straightforward answer on how to become cultured.[28] This made the notion of “being cultured” manipulative and applicable to almost all spheres of life. Sport, or as it was termed, “physical culture,” was no exception, and played a vital part in state policy of “culturization.” As Riordan puts it, “sport was brought into line with the standard Stalin pattern for all activities, becoming a hierarchical State functional organism.”[29] Since the vague term “cultured” was a substitute for “possessing qualities that were inculcated by the authorities,” the need for high physical culture could be attributed to the vision that “The New Man” had to be strong, enduring and disciplined, which is illustrated by this poster:

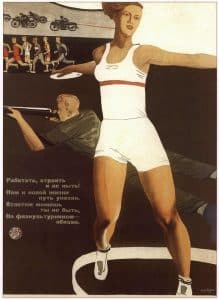

Image 5. “Work, build, do not moan” (1933), source: online

“Work, build, do not moan! // We are shown the path to a new life // You needn’t be an athlete // But must be physically cultured!” the poster states. The central ideologeme is that of “construction.” Even though it is not explicitly stated, what is meant by “the path to a new life” is indeed the path to socialism, which is not, however, given, but constructed; the construction of socialism is discursively linked with the self-construction of the New Man who “works, builds, and does not moan.” Human nature is conquered by “the power of ideas,”[30] and the development of one’s physical culture is perhaps the most telling example of how “The New Man” abandons his/her nature and shapes a second, social nature through the practices of overcoming him/herself. Despite the state’s not being visible, it meticulously controls and promotes such a transformation.

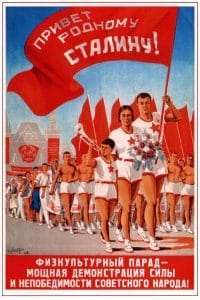

Image 6. “Parade of Athletes” (1938), source: online

This notwithstanding, there was an alternative discourse, in which the state and physical culture were practically inseverable. The affirmation, “The physical culture parade is a mighty demonstration of our nation’s power and invincibility,” uncovers the hidden conjunction between the triad of “culturization,” physical culture and the state. The parade of beautiful youth marching with a giant red flag with a phrase “Greetings to dear Stalin” is a constellation of the three elements: the policy, the individual and the state. The policy is oriented toward the body as an object owned by the individual; yet the strategy of linking the body and the state releases the tension between the individual as the sovereign of his/her body and the state, seeking sovereignty to everything. Put differently, the discursive shift from the body to the state (and vice versa) is grounded in the ideological foundations of Stalinist biopolitics, destructive yet productive, erasing the borders between private and collective and putting private life on the altar of “commonwealth.” The “commonwealth,” however, did not stand for an attempt to improve people’s lives, but was a ticklish ideologeme masking the linear regime’s interests.

A Moveable Gulag

Another totalitarian state’s Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, described politics as “the art of making what seems impossible possible.”[31] The Stalinist state was a schizophrenic state in a sense that it was “built” on a split, a rupture, separating the given and the desired, illusional freedom and constant control, diminishing the private and intensifying the collective, which, translated into the language of biopolitics, meant controlling intangible life (constructive biopolitics) and totalizing death (thanatopolitics: deciding who will die and when). Differences which hindered any ideological singularity were to be eliminated by all means. Stalin’s “Great Break” was a way of dealing with these ambiguities, a course of actions that once and for all had to shape the USSR’s identity – both the state and the people.

This shaping force was Gulag: not the terror itself (though it was possible as “the last instance”), but a certain logic of gulagization, as defined by contemporary Russian philosopher Valery Podoroga, a “machine of terror that […] decoded, displaced and excluded.”[32] The decoding itself was needed to identify in accordance with oppositions: “countryman-foreigner, enemy-friend.”[33] It would be highly erroneous to state that the oppositions eliminated the split (though it was definitely an ultimate object of Stalin’s policy); in fact, the oppositions made the split more visible, as only by identifying and subsequently eliminating “the wrong” could the society of “the right” be established. Gulag served as the grid, enabling the procedure of classifying into right/wrong. At one pole, there were aspirations for the society of new people, a brand new communist world functioning in conformity with the state ideology; at another pole, there was Gulag, the absolute necessity, the inversion of the ‘normal’ order.

Yet the former was impossible without the latter. Both functioned according to the same logic, the logic of law. Precisely the law was the demarcation line between two modes of existence: being and not being. Those who were moral subjects of the ideology were granted life, provided that they were living their lives properly; those who were immoral were put in the conditions of not being, both in a sense of Gulag as a place that shouldn’t be (once there is nothing to purge, the Gulag is not needed anymore) and a place where there are those who shouldn’t be. It is noteworthy that the word ‘purge’ is also marked by a certain ambiguity, being at the border between the material and the moral, as it was in the case of the poster with comrade Lenin. Here too the border is not fixed: any material practice can be turned into an (im)moral deed, and vice versa, and any deed that was instantly coded as moral/immoral had real material consequences.

Image 7. Soviet social advertisement (1930s), source: online

This is evident in the discursive construction of a space. The poster campaigning for a “green, healthy city,” depicting an idyllic space, is precisely an example of the project of the Soviet utopia. “Green pleasures,” however, are inseparable from moral imperatives: “It is the duty of all laborers to make every house, every street an example of sanitary conditions.” As in previous posters, there are discourses of morality, personal and public health and nature tied in one knot. There are no semes typical of a contemporary eco-discourse, such as semes of “preservation” or “protection,” but the discourse of construction is used. It is implied that morality, health, and nature are matters of choice, ideologically approved choice. To be a good citizen means to be dedicated, productive, contributing to the “commonwealth” of citizens.

On the contrary, those who do not want to contribute to the “commonwealth” are destructive, defective, and, in short, a “waste.” Thus, they had to be eliminated. Gulag, as a dystopian space, an opposition to utopian “green healthy cities” and “invincible countries,” was a negative absolute. What was peculiar, both for authorities and prisoners, was that the former considered the Gulag the utmost necessity for the purpose of creating a “clean” society, while the latter saw it as the acme of omnipresent repressions. Even though hidden, or deterritorialized, the Gulag was always immanent to the Stalinist regime; it was at its very core: moral could have been turned into immoral, and the lack of willingness to construct (yourself, a new society) could have been a reason to claim one as a destroyer (who, thus, had to be destroyed him/herself). The Gulag was also another example of Stalin’s biopolitics, his paranoid desire to create a state of New People and to destroy all “waste” so that such individuals could not deteriorate the new society – even by their presence.

The ferocity of Gulag, its very existence, witnesses that Stalin’s aim was not a healthy, happy, and creative nation but the nation as the sum, as the force that could be easily guided and utilized for the state’s needs. Although it was the individual who had to overcome him/herself, to train, to seek perfection, s/he was urged to do it not because s/he was an individual whose value was his/her own being, but because a better part makes a better whole. Thereby use took the place of value. Anne Applebaum, in her extensive study of everyday life in Gulag camps, demonstrates how the prisoners were treated. They lived in dirty and stinky stone or wooden barracks, their movements were restricted, and they were deprived of sleep, food, and baths and forced to do difficult manual work.[34] Those who were not able to bear such a life died, which was proof of their complete uselessness for the regime. From this perspective, the previous poster, compared with the description of the routine of prisoners of Gulag, looks like a phantom promise: everything is good as long as you share our vision of what is wrong; everything is good as long as you strive to be better according to our vision. What is good, however, was not questioned, and the definition of the central notion was always at the leader’s discretion.

Conclusion

Thus, Stalinism made a maxim of the equivalency between being clean and being pure. As Mary Douglas explains, “Purity is the enemy of change, of ambiguity and compromise. Most of us indeed would feel safer if our experience could be hard-set and fixed in form.”[35] Thus, it can be paraphrased that “being clean is equivalent to being clear.” Not only is this true for the clear, ideological obedience of the New Man, but also conversely: the Enemy was depicted as filthy, and therefore unclear and immoral. Indeed, one could find oneself in a complicated situation in which one was not as clean/clear was expected, in a situation of being an enemy of oneself, which was only one thread of a tangled web of meanings: an enemy of oneself, an enemy of the society, an enemy of the State…

The regime’s emblematic “schism,” the rupture between two semi-metaphoric topologies: “the clean green city for good citizens” and “Gulag,” was a codification scheme that functioned almost unconsciously in the mind of perhaps every Soviet citizen. Stalin created the system of “small empires,” in which all situations mirrored the imperatives of the Empire, and Gulag as a system of concentration and extermination camps was the last instance, the concealed central signifier of Stalinist ethical semiotics. This analysis has revealed that even the visual discourse of hygiene and personal health was grounded in such a semiotics. First and foremost, it was characterized by interdiscursivity and metaphorical language that allowed power to function microphysically. Second, it was based on techniques of subjectivation, as personal hygiene and good health were inseparable from the New Man’s features. Third, this discourse functioned in the Stalinist biopolitical paradigm, which synthesized the needs of the body and state as well as allowed the sovereign to exercise power microphysically, being present only discursively. Fourth, the utilized language was often the language of moral imperatives which was founded on the State’s interpretations of right and wrong. Fifth, it emphasized constant, panoptic control: not only did the subject need to control him/herself, but s/he was also surveyed by others as well as the State. Sixth, the ideological interpellation balanced between utopian and dystopian visions of society, between thriving life and decay or even death. Therefore, although the public focus was shifted to propaganda, terror, despite being openly concealed, was a force that structured the discourse and perhaps fortified it.

Finally, even though slogans were formulated as imperatives or commands, the subject had to make his/her decision. The right decision was, as has been demonstrated, to brush your teeth from a young age, neither to drink alcohol nor smoke, to be physically cultured, to participate in parades, to care about others’ well-being – in sum, to take tiny steps toward big goals. The State in its turn was carefully approaching the subject in a tactical movement: not to terrify but to befriend, not to destroy but to make productive, not to face resistance but to gain support, because precisely, as a French publicist Joseph Servan explains, “on the soft fibres of the brain is founded the unshakable base of the soundest Empires.”[36]

Footnotes

References

Agamben, G. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998

Agamben, G. The Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and The Archive. New York: Zone Books, 1999

Applebaum, A. Life in the Camps. In: Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps. London: Penguin Books, 2004

Althusser, L. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses [online]. [Accessed 23 June 2016 at 13:30]

Arendt, H. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Cleveland and New York: Meridian Books, 1962

Chukovsky, K. Moydodyr. WikiTranslate [online]. [Accessed 11 May 2016 at 15:19]

Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of The Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London and New York: Routledge, 1866

Edkings, J., Pin-Fat V., Shapiro M. Sovereign Lives: Power in Global Politics. New York: Routledge, 2004

Foucault, M. Abnormal. Lectures at the College de France 1974-1975. London: Verso, 2003

Foucault, M. The Archaeology of Knowledge and The Discourse On Language. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972

Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1991

Foucault, M., Gordon, C., and Patton, P. Consideration on Marxism, Phenomenology and Power. Interview with Michel Foucault. Foucault studies, No. 14, 2012

Harrison, M. The Economics of Coercion and Conflict. Singapore: World Scientific, 2015

Hellbeck, J. Revolution on My Mind: Writing a Diary Under Stalin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006

Hoffman, D. Stalinist Values: The Cultural Norms of Soviet Modernity 1917-1941. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003

Lynch, M. 6.4. Health. In: Access to History: Stalin’s Russia 1924-53. London: Hodder Education, 2008

Prozorov, S. The Biopolitics of Stalinism: Ideas and Bodies in Soviet Governmentality. IPSA World Congress, Madrid, 2012

Riordan, J. Sport in Soviet Society: Development of Sport and Physical Education in Russia and the USSR. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977

Servan, J. Discours sur l’administration de la justice criminelle, 1767

Suny, R. Stalin and his Stalinism: Power and Authority in the Soviet Union, 1930-53. In: Kershaw, I., Lewin, M. Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997

Thompson, J. Ideology and Modern Culture. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990

Tudge, J. Education of Young Children in the Soviet Union: Current Practice in Historical Perspective. The Elementary School Journal, Vol. 92, No. 1, 1991

Богданов, К. О чистоте и нечисти. Совполитгигена. Политическая лингвистика, №3 (29), 2009

Волков, В. Концепция культурности, 1935-1938 годы: советская цивилизация и повседневность сталинского времени. Социологический журнал, №1-2, 1996

Желизнык, М. Гигиенические практики в советской и современной России. Журнал социологии и социальной антропологии, том Х, Специальный выпуск, 2007

Крупская, Н. Общие вопросы педагогики. Организация народного образования в СССР. Москва: Директ-медиа, 2014

Подорога, В. ГУЛАГ в уме. Наброски и размышления. Index. Досье на цензуру, №7, 1999 [online]. [Accessed 14 May 2016 at 19:34]

Стахановец, №2, 1937