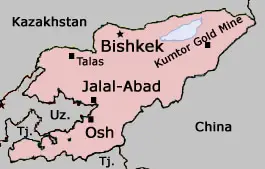

Major locations in Kyrgyzstan (shown in red), including Osh in the south, on the border with Uzbekistan and just inside the Fergana Valley.

Boasting breathtaking mountaintop views and an expansive outdoor bazaar, Osh is one of Central Asia’s major commercial centers and one of its oldest, most socio-culturally diverse cities. Yet the diversity of Osh has clashed in violence in a few recent occasions – primarily between the ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks who populate the city in nearly even numbers. The government has tried to stabilize the situation and efforts have been made alleviate the ethnic tensions, with some success. However, Osh, in many ways far removed from the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek, has come to represent the diverse and divided history of Kyrgyzstan and the wider tension between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

Geography and Demographics

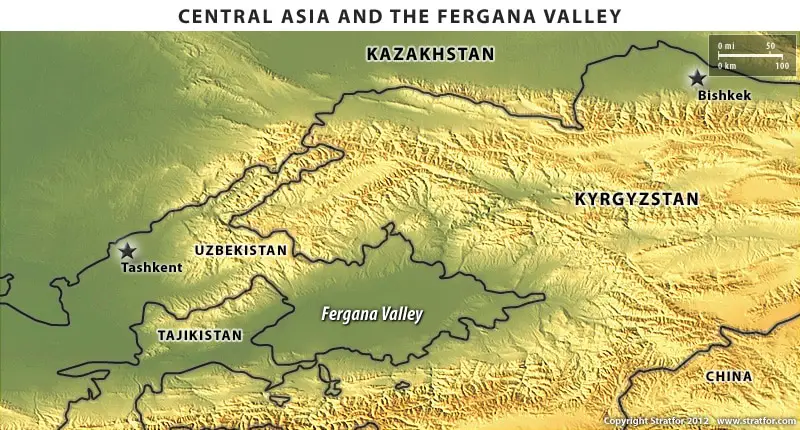

Osh, considered the “southern capital” of Kyrgyzstan, is situated where the southern ranges of the Tian Shan give way to the irrigable and fertile lowlands of the Fergana (or Ferghana) Valley. At around 8,500 square miles, the Fergana Valley is roughly the size of Israel. Two major rivers and numerous streams and tributaries make the valley highly fertile, and the area has an overall warm, dry climate. Cotton production, instituted by the Soviets, is central to the regional economy, as are farming and livestock breeding. The wider area also offers several natural resources, including coal, iron, sulfur, salts, and precious metals, which have led to recent growth in industry and mining.

The Fergana Valley has long served as a bread basket and trading hub for the civilizations that have occupied the surrounding mountains. Thus, the area has traditionally been ethnically diverse, with substantial Uzbek, Tajik, and Kyrgyz populations which tend to live in large pockets rather than within easily discernible boarders. The area is also home to significant Russian, Kashgarian, Kipchak, Bukharan Jew, and Romani minorities.

The city’s geographic location has encouraged the comingling of nomadic herders, sedentary farmers, and urban merchants, lending the city a certain dynamism that it has largely preserved over the centuries.

Kyrgyzstan’s current population of around 5.5 million is composed of about 69% Kyrgyz and 15% Uzbek, Osh, by comparison, was 43.0% Kyrgyz and 48.3% Uzbek in 2009. The population of the immediate city was around 258,000 in 2009, making Osh roughly the size of Buffalo, NY, while the entire metropolitain area has been estimated at as many as 500,000.

A satellite image of Kyrgyzstan and surrounding area with Kyrgyzstan’s territory highlighted. The vast majority of the country is mountainous. Osh & The Fergana Valley are separated from the majority of the country by a substantial mountain range. Photo from Wikipedia Commons.

Early History of Osh and the Kyrgyz-Uzbek Divide

While it is uncertain exactly when Osh was first founded, the Fergana Valley has been inhabited since at least the 5th century BC, when the valley was part of Sogdiana, a loose confederation of Iranian peoples who owed fealty to the Persian Empire of Darius the Great. Alexander the Great defeated the Sogdians in the fourth century, incorporating their lands into the Macedonian Empire. After two centuries of Greek rule, the valley was invaded by the Indo-European Yuezhi from the east and the Iranic Scythians from the south. While ownership of the land changed, the Hellenic culture largely remained unchanged and the agricultural, pastoral, and transportation infrastructure remained central to the local economy.

The valley, when discovered by the Chinese, likely in or before the second century BC, was referred to as “Dayun.” This was likely the first time that the Chinese had interacted with Indo-European peoples and ancient Chinese historians describe the valley as a land full of exotic people and goods that became sought after by Chinese merchants and, later, the Chinese military who were particularly interested in the horse breeds there. This helped lead to the establishment of the Silk Road by the Chinese in the first century BC. The Fergana Valley, and particularly Osh, became a major commercial and logistical center as well as fertile agricultural area that bordered several kingdoms and which, the Chinese documented, was only lightly defended by the local peoples. Invasions, including those by the Chinese, would thus bring a certain amount of instability to the prosperity the region’s geographic advantage gave it.

A tourism video in Russian, with some Kyrgyz, about Osh discussing its history and landmarks.

By the eighth century, Osh was a well-known silk production center and a convenient location to rest and resupply along the Silk Road. Around the same time, the region was conquered by the Arabs, who introduced Islam to the area before being defeated and displaced by the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan. When the Golden Horde disintegrated, Osh and the surrounding territory merged into the Chagatai Khanate and then the Mongol-Turkic Empire of Timur. Timur’s heir, Babur, is said to have pondered his future on Sulayman Mountain just outside of Osh, where he resolved to found what would become the mighty Mughal Empire which at one time covered most of present-day India and extended deep into Central Asia.

The Mughal Empire lasted until 1857, and while the valley and Osh were lost to the empire early in Babur’s reign and never recovered, the Persian, Turkic, and Islamic influences of the Empire did become dominant there and were maintained by the series of states that would come to control the area. By the time the Russians incorporated Osh into their empire in 1876, the Fergana Valley was widely known for influential Islamic thinkers and proselytizers, whose impact could be felt deep inside Russia, China, and East Asia.

Major waterways within the Ferghana Valley. Note that all major water sources flow from mountains on Kyrgyz territory and most can be affected by dams and hyrdroelectric stations within Kyrgyz territory. This has been the source of considerable conflict within modern Kyrgyz-Uzbek relations. They valley is also densely covered by an extensive network of mostly Soviet-built irrigation canals. Photo from American University.

Tsarist Russia further developed irrigation and industry across the valley in part to ensure their continued hold on the gains that they made in Central Asia against Great Britain in the famous “Great Game” during the 19th century.

After the revolution, and after a very brief period as part of an independent Turkestan, Osh and the valley were absorbed into the Soviet Union. In 1924, the eastern part of the Fergana Valley was divided between the newly created Soviet republics of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, even though the entire valley had traditionally been heavily Uzbek. Further, when the Soviets industrialized Osh during the 1960s, they encouraged the local Kyrgyz to move from the countryside into the city and take jobs in manufacturing and public administration.

These moves were made to encourage integration among the peoples of Central Asia as well as to keep any political power they might gather divided. They also resulted in considerable tensions between the traditionally nomadic Kyrgyz and the settled, agricultural Uzbeks.

To make matters worse for Kyrgyzstan, little was done to improve communication and transport between the republic’s long-divided halves which, while both heavily Kyrgyz, had historically remained largely isolated from each other. This helped ethnic and tribal identity take on a new and heightened significance in Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia in general.

As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate during the late 1980s, ethnic relations in the Fergana Valley deteriorated as well. Kyrgyz and Uzbek communities each formed their own activist political organizations. The Uzbek Adolat (“Justice”) movement called for the establishment of an autonomous Fergana Valley region within the Kyrgyz SSR, and even pushed for full integration with Uzbekistan. Other Kyrgyz political groups, meanwhile, called for a takeover of Uzbek agricultural land.

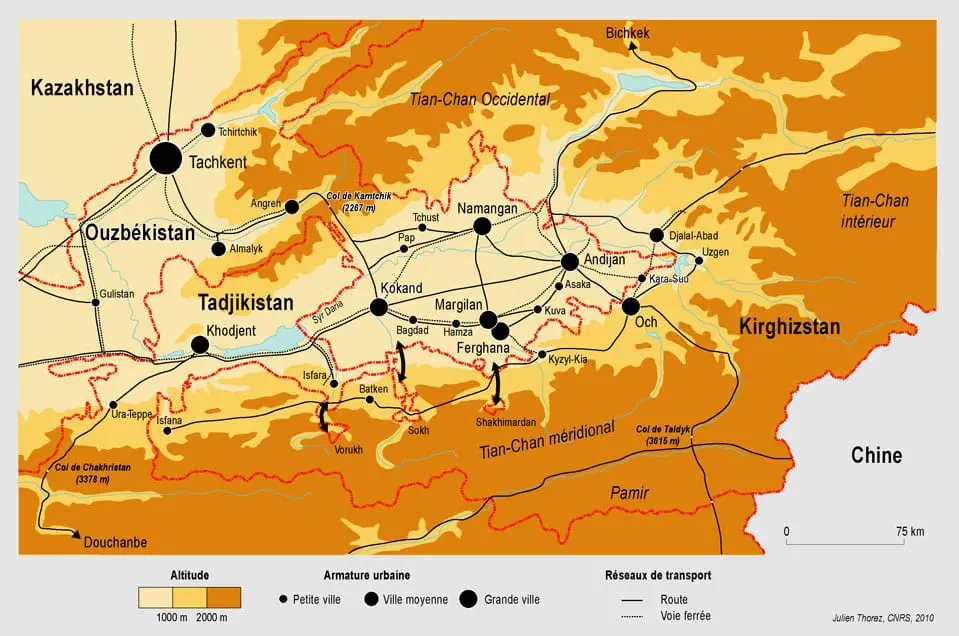

A topographic map (in French) showing major populated areas and transport routes in the Fergana Valley. Roads are shown in solid lines, rails in dotted grey. Note that Osh (Och) shares much more transport integration with Uzbek and Tajik territory than it does with Kyrgyzstan. Map by The French National Center for Scientific Research.

The tension flared into full-scale interethnic warfare in June 1990, when an Uzbek collective farm in Osh was transferred into Kyrgyz hands. Though Soviet paratroopers were deployed within hours and successfully stabilized the situation, the incident ignited widespread violence in Osh and the surrounding area, resulting in over 300 deaths and more than 1,200 injuries. In the subsequent investigations, almost 1,500 legal cases were filed and 300 people put on trial, resulting in 48 individuals—mainly Kyrgyz—convicted for charges including murder, attempted murder, and rape.

Osh and Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan

As the USSR fell, Kyrgyzstan also declared independence in late 1991, although most Kyrgyz had voted in a referendum to maintain the USSR. As one of its last actions, the Soviet legislature of Kyrgyzstan elected Askar Akayev, an ethnic Kyrgyz from northern Kyrgyzstan, to the new post of President of Kyrgyzstan.

Independence did little to solve the longstanding and increasingly divisive ethnic divide in Osh and or the regional divide between southern and northern Kyrgyzstan. President Akayev was soon accused of corruption and favoring the northern provinces and ethnically Kyrgyz population. Following his re-election in 1995, Akayev expanded his presidential powers and arrested many of his opponents, such as parliament member Azimbek Beknazarov from the southern city of Jalalabad, located just 30 miles from Osh, on charges of political abuse in early 2002.

Demonstrations at his trial in Jalalabad quickly turned violent. Six protestors were killed by police. Demonstrations soon spread to other cities including Osh and Bishkek with protestors demanding the resignation of Akayev. Akayev promised to step down at the end of his term in 2005, but the protests and regional and ethnic tension continued.

A short video from Stratfor on “Kyrgyzstan’s geographic challenge,” which covers, in part, the internal geographic and ethnic split between Osh and Bishkek.

When parliamentary elections were held in early 2005 and only six seats were won by the opposition party (whereas both of Akayev’s children received their own seats), many believed that the election had been rigged. Osh and Jalalabad became a nexus of yet another wave of anti-government demonstrations, with the protestors again demanding Akayev’s resignation. On March 24, 2005, several thousand protestors besieged Akayev’s presidential residence in Bishkek and seized control of the capital, Osh, Jalalabad, and numerous other towns and cities in southern Kyrgyzstan. The event became known as “The Tulip Revolution.” Akayev was forced to flee the country and resigned on April 11.

In the wake of Akayev’s abdication, Bakiyev, an Uzbek whose political base was planted in Osh, Jalalabad, and southern Kyrgyzstan, was named interim head of the government. He was elected president in 2005. The political unity proved short-lived, however. The parliament fractured as Bakiyev was slow to institute the limits on presidential power promised by the Tulip Revolution. Instead, Bakiyev pushed through a controversial series of constitutional amendments aimed at increasing presidential power, and called for new parliamentary elections in December 2007. In these elections, the pro-Bakiyev faction gained 71 of 90 seats. The opposition protested the elections as rigged.

Accused of corruption, cronyism, and nepotism, Bakiyev’s administration continued to deal with Kyrgyzstan’s chronic ethnic and regional divides. The Kyrgyz distrusted his Uzbek roots, while Uzbeks claimed he curried favor to the Kyrgyz during his rule. The global financial crisis in 2008 additionally threw Kyrgyzstan’s economy into a recession. When a spike in utility prices led to a wave of uprisings in Osh and throughout Kyrgyzstan in April 2010 Bakiyev’s government crumbled in yet another revolution.

Roza Otunbayev, an ethnic Kyrgyz born in Bishkek, led the opposition in declaring a new provisional government, whileBakiyev went into exile in Belarus. The ensuing power vacuum in Osh and southern Kyrgyzstan touched off a three-way struggle between supporters of the Provisional Government, supporters of the ousted president Bakiyev and representatives of the ethnic Uzbek community in Osh who supported neither.

Hoping to gain popular support from his fellow Uzbeks, Kdyrjan Batyrov—a wealthy businessman and former member of parliament—gave a speech in Osh on May 15, 2010 calling for increased Uzbek political participation in Kyrgyzstan. Ultimately, however, Batyrov’s speech only added to the divisive political atmosphere of the moment, and was interpreted by Kyrgyz leaders as an ethnically charged call for Uzbek revolution. Meanwhile, the Provisional Government, in rapidly replacing pro-Bakiyev security services personnel, also touched off heightened ethnic and political unrest since many of Bakiyev’s security forces had been recruited from Osh and the southern Kyrgyzstan.

Topographic map of the Ferghana Valley with political borders shown. The land flows most naturally into Tajikistan and the valley’s major rail line and transport route flows there as well (see transport map above). Map from Stratfor.

City of Sorrow: Osh and the 2010 Riots

On May 13, 2010, supporters of Bakiyev seized various administrative and government buildings in Osh and Jalalabad. While the situation in Osh did not immediately lead to serious violence and was defused successfully, Jalalabad was the site of clashes between hardcore Bakiyev supporters and combined supporters of both the Provisional Government and Batyrov’s Uzbek movement. Together, they recaptured the administration building in Jalalabad and set fire to Bakiyev’s houses in his family’s hometown of Teyit. Meanwhile, the tension in Osh appeared to have at least temporarily subsided. In reality, however, the ethnic and political unrest continued beneath the surface, as many local Kyrgyz in the south of the country were mobilized by opponents of Batyrov.

On the evening of June 10, a clash between Kyrgyz and Uzbek youth gangs outside Osh’s casino touched off ethnic rioting at a nearby dormitory and in various parts of the city. Police and security forces were unable to disperse a large crowd of angry Uzbeks, whose presence prompted a gathering of equally incensed Kyrgyz, many of whom rushed into the city from the surrounding suburbs and countryside to join the riots. At 2am on June 11, the Provisional Government declared a state of emergency and introduced a curfew, but shortly afterwards the burning and looting of Osh’s large bazaar commenced. Armed Uzbeks blocked the central road which connects Osh to both the airport and Bishkek. Likewise, mass Kyrgyz mobilization from villages to the west and east of Osh began. Automatic weapons were distributed—allegedly by ethnic Kyrgyz in the government security forces—to many Krygyz, who also seized some armored personnel carriers from military and police forces and used them to destroy Uzbek roadblocks and barriers throughout Osh. By the afternoon of June 11, ethnic riots began between the Kyrgyz and Uzbeks, resulting in widespread violence, looting, and property destruction.

A report by AlJazeera English on the refugees that attempted to flee Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan as the riots escalated.

As rumors began to spread on June 12 that nearby Uzbekistan was going to intervene on behalf of the Uzbek population, the violence in Osh briefly deescalated as some of the Kyrgyz security forces pulled out. Ultimately, however, no foreign intervention occurred, either from Uzbekistan or from Russia, to whom the Provisional Government appealed for assistance. Then-President Dimitri Medvedev replied that the affair was an internal matter of Kyrgyzstan and the Kremlin could not get involved.

The riots ultimately resulted in 470 deaths and over 1,900 injuries in Osh alone. Of those Uzbek refugees who fled across the border, around 3,000 were hospitalized for various wounds. More than 2,600 buildings and homes were totally destroyed, and the property damage to Osh was extensive.

According to a report published by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry at the request of Roza Otunbayeva and the Kyrgyz government, the violence was largely the result of the “ineptitude and irresolution” of Otunbayeva and the Provisional Government. The report—which was based on interviews of nearly 750 witnesses, 700 documents, about 5,000 photographs and 1,000 video extracts—found serious violations of human rights and international law, and noted that if some of the evidence of atrocities in Osh were proven beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law, those acts would amount to crimes against humanity. The findings of the KIC infuriated and alarmed the Kyrgyz government, and the commission’s chair Dr. Kimmo Kiljunen, a Finnish citizen and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Parliamentary Assembly’s special representative for Central Asia, was declared persona non grata by the Kyrgyz parliament.

The Mayor of Osh, Melis Myrzakmatov, has risen in his political profile thanks, in large part, to his role in the riots concentrating Kyrgyz nationalist support around him. Myrzakmatov has published a book which presents his own account of the June 2010 riots, in which he takes a strongly anti-Uzbek stance and largely portrays Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan as radical separatists. The national political party which Myrzakmatov lead, Ata-Zhurt (“Fatherland”), won 28 of 120 seats in the 2010 parliamentary election, making it the first of the five political parties in Kyrgyzstan to made the party the first of five parties to surpass the support threshold of 5% of eligible voters necessary to enter parliament, and giving Osh and the surrounding area even more say in national politics.

Osh itself remains a relatively popular tourist destination in Central Asia and a welcome rest stop for those traveling the ancient Silk Road route. Progress has been made to better connect the city with both the rest of Kyrgyzstan and the rest of the world. The long highways linking Osh to northern Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have recently been improved, and daily flights are now offered to and from Bishkek, Moscow, and Istanbul. However, the border crossing to Uzbekistan is still often closed, sometimes with little or no warning.

2012 crop distribution for the Fergana Valley, superimposed on a satellite photo of the area. Map produced by Monitoring, Evaluation & Learning.

Nevertheless, major industries, including cotton and tobacco processing, textile production, and food processing, continue to supply the city with jobs and the population is growing again after a brief contraction in 2011.

The city’s famous market has been rebuilt since being gutted by fire and looting during the riots, and is bustling once more as Kyrgyz and Uzbek merchants sell their wares side-by-side. Yet the bazaar, and the entire city, are still permeated by the memory of recent events and a pervading tension still hangs in the air. While the ethnic and cultural diversity of Osh—and the entire Fergana Valley—is one of the area’s most unique aspects, it has also led to continual political unrest that has impeded its overall development.

More on SRAS Programs in Central Asia