Moscow is not just a city. It was a fort that became a city, that became a state, that became an empire, that became a superpower. Moscow maintained an unlikely meteoric rise to the global stage that continued steadily over the course of several centuries. Modern Russia can be understood as a product of this unique development: as a country that was rapidly assembled, piece by piece, from the epicenter of its capital by the will, luck, and political maneuverings of rulers that have been historically based in that city.

Geohistory: the Foundations of Moscow and the Russian State

Moscow was officially founded in 1147 by Yuri Dolgoruki, the Grand Prince of Kyiv. The name “Moscow,” applied to both the new garrison and the adjacent river, may have come from the Slavic, Baltic, or even Uralic or Finno-Urgic peoples who lived in or traveled through the land for centuries before.

While there is debate on the origin, there is little debate on the meaning of the name; in all four cases, the name refers to swampland, as this is what much of the region originally was.

Moscow lies near the center of Earth’s largest, flattest expanse of territory. With no natural defenses to slow down invaders, Moscow developed a policy of continually expanding its boarders, conquering and absorbing potential adversaries and placing more distance between the Russian heartland and those adversaries.

In 1147, Moscow was a small fishing village inhabited by Slavic peoples who had begun draining the surrounding swamps in the previous century. Moscow was founded at a time when Yuri’s powerful Kyivan principality was expanding northward, colonizing and consolidating lands stretching towards the Arctic. Moscow’s location gave the principality another access point to the Volga River system, which provided transport to the principality’s new northward lands and provided increased opportunities to expand further east on the Volga which was then already part of economically valuable trade routes between Europe and Asia.

Although the location had value to Kyiv at the time, there was little reason to believe that the new garrison would one day become the geopolitical center of a vast swath of the Earth. The Moscow River is a relatively small offshoot in the Volga system. Moscow’s placement provides an access point to, but not strategic control over any part of that system. Further, unlike most major European capitals, Moscow had no direct ocean access for wider, more valuable international trade and communication. The weather there is wet and the soil soft and moist, creating challenges for growing crops, storing food, and constructing infrastructure. The surrounding swampland bred mosquitos, which spread disease. A lack of accessible quarries meant that Moscow was long dependent on wooden architecture and, thus, susceptible to fires. Beyond Moscow, the vast expanses of Eurasia that it would one day control lay mostly flat for hundreds of miles in any direction. There was nothing to stop the numerous invading armies that would constantly challenge it. In fact, Moscow’s best natural defense was the bad weather and boggy soil that made inhabiting it a challenge in the first place.

Moscow, perhaps more than any other city on Earth, is a testament to the fact that while geography often gives advantages or disadvantages, sometimes the force of history and the will of man can rival even the power of nature. Moscow grew from the personal ambitions of its rulers, ambitions that were given an immediacy and perceived necessity by the challenges that those ambitions faced.

Kyiven Rus, a few years before Moscow was founded. Moscow’s future site, on a relatively minor river, has been added with a red arrow. The shaded area at the north was under colonization by Kyiv at the time. For the original, larger map, click the photo.

The Early Development of Moscow

Ten years after Moscow’s official founding, a wooden wall was built to protect it, forming the original Kremlin. At about the same time, Kyiv proclaimed the Vladimir-Suzdal Principality to further consolidate its governance of the area. Moscow was then a minor outpost near the border of that principality.

Development was slow and, when the Mongols invaded in the first half of the 13th century, Moscow was one of several cities burned to the ground. In the 1260s, Moscow was inherited by Daniel, Alexander Nevsky’s two-year-old son. By tradition, the youngest son inherited his father’s least valuable possessions.

By his teens, Daniel proved to be an adept ruler who made the most of the chaotic times that surrounded him. With Mongol rule established and with the death of Nevsky, who had been a strong and popular ruler, the area fractured into competing forces. The Mongols also effectively cut the principality from Kyiv, whose empire would collapse by the end of the century. Mongol rule would greatly affect the development of the Russian language, culture, and political systems.

By shifting his alliances between his extended family members and by keeping Moscow away from most direct conflicts, Daniel maintained influence in the region’s larger and more powerful cities, particularly the rising capital of Vladimir. By 1296, his influence was such that the Prince of Ryazan, considering Daniel a potential future adversary and likely an easy, youthful target, attempted to conquer Moscow with the help of allied Mongol forces.

Daniel, however, decisively defeated the invasion and even secured from Ryazan control of the Moscow River when Ryazan sued for peace. With control of the river, Moscow’s economy grew at an expedited pace. Daniel’s victory was one of the first achieved by the Russians over the Mongols and would become part of the narrative of a rising Russian nationalism. It was also the only major military battle that Daniel ever led (he otherwise fought under his more powerful brothers).

Shortly before Daniel’s death, his childless nephew and ally, Ivan of Pereslavl, bequeathed to Daniel all his lands, including Pereslavl, the former residence of Alexander Nevsksy that had served as a second capital under Nevsky’s grand rule. The acquisition increased Moscow’s wealth and political power.

By the time that Daniel died in 1303, Moscow had grown into a relatively small regional power of note with expanding political and territorial influence, economic potential, and cultural value as the pious Daniel had founded the city’s first monasteries and major churches, including the Danilov Monastery, which still exists and now bears his name.

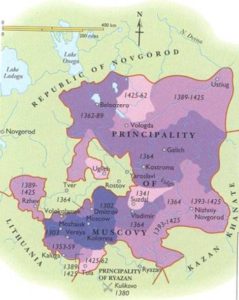

The expansion of Moscow Principality from Daniel (darkest purple in the south) ca. 1300 to Vasily II (light pink) in 1462. Note the surrounding rivals: the Mongols, Ryazan, Lithuania, and Novgorod. For a larger version, click the map.

Yuri, Daniel’s eldest son, inherited his crown. Yuri’s rule was much more aggressive – taking new lands to the West and North of Moscow from the Prince of Smolensk and the Swedes to secure access to the Neva River system. That system flows to the Baltic Sea, the closest point of direct ocean access available to Moscow. Yuri would gain only indirect access, however; Moscow’s ships still had to pass through the lands of other powers to actually reach the sea. Moscow would spend centuries trying to gain a direct foothold on the Baltic and uncontested ocean access.

Yuri aggressively sought political influence with the Mongols, which were then solidly in power and thus the most direct way to secure his inheritance from his increasingly covetous rivals.

Moscow’s lasting influence was solidified under Yuri’s son, Ivan. Ivan successfully petitioned the Mongols for the title of Grand Prince, giving him the ability to collect taxes from all Russian lands and making him the single point of contact to pay the tribute demanded by the Mongols from those diverse and fractured lands. Ivan used his new source of finances to build infrastructure, buy land, and offer loans to surrounding principalities (and often annexing them when payments fell behind). He even bought more Russians to populate his lands (from the Mongols who had captured them elsewhere). As Moscow grew, and was comparatively safe from Mongol raids (due to its pledged Mongol loyalty and geographic buffers), more people from surrounding areas moved to live under the protection and growing prosperity of Ivan. In 1325, the Metropolitan of the Russian Orthodox Church moved the seat of his See from Vladimir to Moscow.

Thus, over the course of just three generations, Moscow skyrocketed from being the region’s least-valuable garrison to effectively competing with the other regional powers around it – including Tver, Ryazan, Novgorod, and even Vladimir, the official capital. Moscow took full advantage of the political situation caused by the Mongol invasions and built wealth and power by acquiring control of additional lands, full control of the Moscow River, and involving itself directly in the Mongol-imposed governance structures. Moscow’s wealth and power, although still small and very much confined to its region, were growing.

Moscow still faced all the same challenges, however. It lacked ocean access, it ruled flat, indefensible terrain in a challenging climate, and was surrounded by potential adversaries. Many of those rivals, particularly Novgorod and Ryazan, were comparatively quite powerful, to say nothing of the threat Moscow might face from the Mongol overlords should it fall from favor.

Cracks in Mongol Rule

The Mongols continued to favor and strengthen Moscow, however. They did so particularly as a line of defense against the growing power of the Lithuanians to the West. The Mongols were long Moscow’s greatest asset; eventually, Moscow became a major liability for the Mongols. Moscow became strong enough to dominate the surrounding lands and defend against encroachments, and, later, strong enough challenge the Mongols themselves.

This began in 1362, when then-Prince of Moscow Dimitri Donskoi sought approval from the Mongols for a formal takeover of Vladimir, the former regional capital. Mamai, then leading the Mongols, denied the takeover, perhaps trying to taper Moscow’s growing power, and awarded the city instead to the rulers of Tver, a rival of Moscow.

A very brief video on Kyivan Rus, the Mongol invasion, and Russia through 1584.

Also in 1362, Lithuania took over Kyiv and sought to advance towards Moscow. Thus, in 1366, sensing threats from both sides, Donskoi began construction of white limestone walls to replace the oak walls of the Kremlin. These were finished just in time to withstand multiple sieges from Lithuania – in 1368, 1370, and 1372. They would also prove invaluable against many future Mongol attacks.

By 1375, Donskoi negotiated with Mikhail II of Tver (whose chief benefactor had been the now-defeated Lithuanians) to take possession of Vladimir. However, the Mongols still refused to recognize the transfer. Donskoi, who knew that the Mongols at that time were weakened by internal divisions, and having pacified the Lithuanians by withstanding their sieges, mounted a military challenge against the Mongols that would transform the surrounding political landscape.

Initially defeated in his 1377 offensive, Donskoi defended successfully against the 1378 Mongol counterattack. Both sides doubled down and prepared for a great battle. Mamai concluded an agreement with Lithuania, his archrival, to join forces and defeat Moscow. Many Russian princes that had sworn allegiance to the Mongols, including Mikhail II of Tver, rebelled and joined Moscow. Several Russian princes that had allied previously with Lithuania against the Mongols broke their Lithuanian ties and joined Moscow. The Principality of Ryazan split, with the Prince there pledging a large armed force to the Mongol side, but with many of his boyers, in fact, defecting to Moscow. The leader of the Russian Orthodox Church officially gave his blessing to Donskoi and contributed a contingent of warrior monks.

In 1380, Donskoi managed to attack the Mongols before reinforcements could arrive from either Lithuania or Ryazan. Donskoi, despite being outnumbered nearly 2-1, defeated the Mongols. The Lithuanians recalled their troops en route and Ryazan was forced to bow to Moscow. Although a massive Mongol army sent from Central Asia would burn Moscow and regain control of the city in 1382, Donskoi, by the end of his reign in 1389, had made Moscow a symbol of Russian resistance and a center for Russian nationalism. He had also, despite eventually losing to the Mongols, more than doubled the size of the lands under Moscow’s control and, in fact, now claimed the right from the Mongols to hand down the title of Grand Prince (with its functions of general tax collecting) to his heirs without first consulting the Khan. This ensured that Moscow’s greatest asset was now under its own control.

Vasili the II saw the most troubled reign of any Moscovite prince to date. A civil war saw him imprisoned and blinded. However, he still expanded his territory and the power of the Moscow throne by the end of his time in power.

Origins of the Muscovite Civil War

Although Moscow was now a sizeable and wealthy state, after Donskoi’s reign, many of the advantages that had contributed to its meteoric rise were lost: freedom from Mongol invasions and a series of uncontested successions. However, even the loss of these advantages did not stop Moscow’s rapid expansion.

In 1392, under Vasily I, Donskoi’s son, Moscow annexed Nizhny Novgorod, another former rival. In 1395, Vasily claimed the infighting within the Mongol empire prevented him from transferring his tribute: he did not know to whom to send it. He kept collecting taxes as the Grand Prince, but put the full force of these finances into his own kingdom – rapidly expanding north and east – taking Suzdal, Vologda, and conquering the Komi peoples. By 1408, the horde regrouped and retaliated, burning several cities including Moscow to reinstate their authority. By 1414, Vasily was again a vassal of the horde, but now a much larger and more powerful vassal, and resumed paying tribute.

Vasily II, eldest son of Vasily I, assumed the throne in 1425. However, the former ruler’s brother, Yuri, claiming that he was the oldest eligible male heir, received permission from the Mongols to take Moscow by force. The Mongol leader may have hoped to have a new prince that would be more indebted to him and less likely to rebel. The Mongols may have calculated as well that the move would spark a civil war, one that might pull Moscow’s valuable surrounding duchy apart, giving Moscow’s ruler fewer resources and thus making him more manageable. In any case, in the midst of the 28-year Muscovite Civil War that followed, the Khanate of Kazan was established and the new leader there, to establish his supremacy over Moscow, also attacked while the city was weakened.

Vasily II was defeated several times, taken prisoner, and even blinded by his enemies. However, those enemies always left him alive, perhaps fearing retribution from his numerous supporters. Each time he regained his freedom, he regrouped and attacked again.

At the end of the war, Vasily remained much as he had begun: with his crown and lands and as a Mongol vassal. Given the circumstances, this was itself an incredible feat. Further, Vasily would also still have time to significantly expand Moscow’s power and influence by the end of his reign.

In 1453 (the year the Muscovite Civil War ended), Constantinople, then the center of Eastern Orthodoxy, was taken by the Turks. The Orthodox Patriarch there ceded his primacy to the Pope of Rome. Moscow, like many Orthodox centers, refused to recognize the new hierarchy, which would have brought all of Christianity under a single leadership for the first time since the fall of Rome.

Vasily II nominated a new Metropolitan, Jonah, to take over religious leadership of the lands of Rus. Jonah was elected by the bishops of Moscow – the first such election without the oversight of Constantinople. Although controversial, this advanced Russian nationalism and secured Moscow’s place as a center for that nationalism. This would be a valuable tool against Mongol rule.

Ivan III – Consolidation of the State

Until Ivan III, son of Vasily II, the Grand Duchy of Moscow had been a complicated amalgamation of lands, many of them semi-autonomous, but all united in various ways and to various degrees under Moscow. Ivan would change this.

Lands added to the Moscow Principality under Ivan III after 1462 are shown in green. This includes the very large Novgorod Republic (the solid green section at the top). Its most valuable lands were in the Arctic, and were rich in furs. For a larger version, click the map.

Ivan III was born in the midst of the civil war; it ended when he was 13. His next nine years were spent taking care of his blind father and increasingly shouldering the work of running the duchy. By the time he inherited the throne in 1462, at the age of 22, he was an experienced leader and was convinced that only strong, centralized leadership would hold his state together. He was also heir to the already well-established Russian belief that the only way to make sure the borders of the state were secure, in the face of numerous adversaries, was to continually grow them at the expense of those adversaries.

Ivan began by confronting Novgorod, a Slavic republic that drew considerable wealth by harvesting furs in the vast swaths of Arctic lands that it controlled. The Mongols required Moscow to gather tribute from Novgorod although the Mongols had never actually sacked that city (probably due to the severe boglands surrounding it). Novgorod had, like Moscow, often maneuvered for more independence, but from Moscow, not the Mongols.

The split between Moscow and Novgorod ran deep. Novgorod’s highly institutionalized and decentralized system of government in which princes served at the invitation of the people stood in stark contrast to Moscow’s centralized and personalized ruling traditions. In fact, Novgorod’s social systems were much closer to what had developed in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during its golden age. Novgorod had constant contact with the Poles, a fellow Slavic people, in maintaining their trade routes to Europe.

As Novgorod saw Moscow annexing more Slavic lands while the Mongol empire crumbled, Novgorod sought to protect its interests by making a pact with Poland. However, under a treaty that Novgorod had signed with Moscow, all Novgorod’s actions in the realm of foreign affairs were to be approved by Moscow first. Such approval had not been sought or given. Further, the Poles held an alliance with the Mongols at that time and Ivan saw Novgorod’s alliances as truly enveloping Moscow in united rivals. Ivan moved to enforce the treaty by invading.

Ivan defeated Novgorod, confiscated its most valuable lands, and demanded a treaty giving Moscow even more authority. Ivan’s subsequent attempts to stamp out opposition in Novgorod by diplomacy and, increasingly, arrests and violence proved unsuccessful. Seven years after the first invasion, Ivan invaded again, slaughtering the population, burning parts of Novgorod, and demanding, and receiving, the complete political subjugation of the city in 1478. The city’s population, however, would continue to be restless against Moscow rule for at least the next two generations.

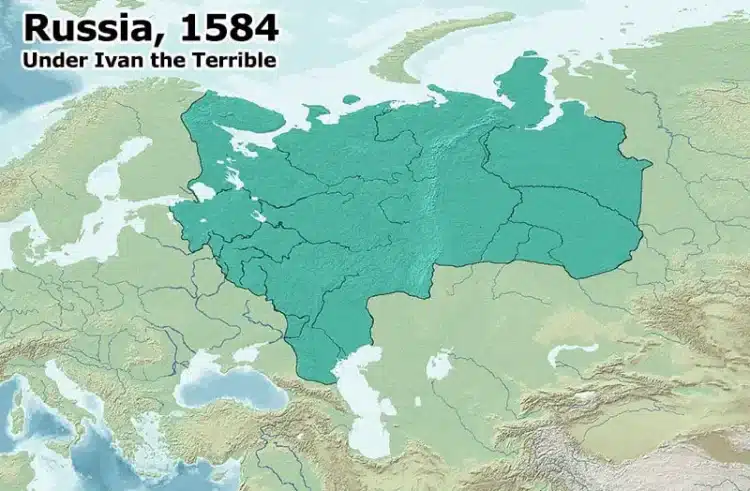

A map showing the full expansion of the Russian Empire. Areas marked in blue were under Russian control at the end of the reign of Ivan III. Ivan IV added the vast majority of what is marked in purple. Note that the area marked in blue around the Baltic Sea was not secure enough nor held for long enough intervals to be developed as economically or militarily viable territory until after 1721. For a larger version, click here.

The fall of Novgorod was important for many reasons. It represented the most significant expansion of Moscow’s borders to date, an expansion that would only continue to escalate in the coming years. It also represented the fall of what was the most significant ethnically Russian rival to Moscow. Thus, this marked the beginning of Ivan’s long campaign to consolidate his holdings under his direct authority while making Moscow the most powerful political base of Russian nationalism.

Ivan went so far as to declare war on his brothers to ensure that their land was completely controlled by him. Boyars were effectively reduced to civil servants, carrying out Ivan’s will. To make sure that this could be done effectively, Ivan had the Sudebnik, Russia’s first code of laws, drawn up. The Sudebnik was largely concerned with regulating land ownership and facilitated continued takeovers by Ivan. It also, however, provided a unified system of justice, codified rights and obligations for all classes, and allowed for serfs to change masters under certain conditions if they wished.

Ivan refused to pay the customary Mongol tribute in 1476, marking yet another attempt by Moscow to declare independence. When the Mongols arrived in 1480 with a large force of horse mounted archers and spear-carrying warriors, Ivan met them with a smaller force equipped with newly acquired firearms and cannons. The Mongols retreated and, before they could launch a new offensive, the Golden Horde, long fractured and struggling, collapsed. The various Mongol states that emerged from that fall would still pose challenges for Moscow, but never again would Moscow face a united Mongol front or again pay tribute to the Mongols.

After the breakup of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Ivan pushed West, into former commonwealth lands, as far as possible. Ivan hoped to gain direct access to the Baltic and also to realize what he saw as a rightful claim to Kyiv. Considerable advances towards these goals were made, including establishing a fort on the Narva just a few kilometers from the Baltic Sea and deep advances south towards Kyiv, but these were soon lost again as his rivals regrouped and counter attacked.

Despite this, by the end of his reign, Ivan III had tripled the size of his lands and consolidated his rule into what was shaping into a massive consolidated monarchy. Ivan’s son, Vasilli II, continued his policies, further consolidating and expanding, mostly at the expense of the Lithuanians and the Poles.

Ivan IV – The First Tsar

Ivan IV, who would be known as Ivan the Terrible, led the most dramatic and violent rule of any Moscow leader before him starting in 1533. This would be largely driven by ambition but also by his proclivity to mental illness and fits of rage coupled with an intensification of many challenges that Russia had traditionally faced. In general, however, his rule can be seen as a continuation of what came before and as driven by the geographic constraints of his land and by the historical memory handed down to him by past leaders.

Ivan had himself crowned “Tsar of All Russia” in 1547 when he was just 16, pushing for a leadership role molded off Caesar of Rome – absolute and answerable only to God. He created the Zemsky Sobor, a legislative organ that included boyers, clergy, and local leaders. He expanded the rights of local governments at the expense of the aristocracy and solidified the rights of serfs to leave their masters under certain conditions. He reformed the Russian church by posing 100 questions to church leaders and calling them to a conference to have them answered. Although he experimented with somewhat more inclusive forms of governance, Ivan also founded the Oprichniki – a group of individuals who were granted land in return for acting as secret police – seeking out and eliminating any threat to Ivan’s rule.

Ivan’s attempts to push his borders to the Baltic Sea soon saw him fighting the Swedes, Latvians, German Hanseatic League, and the Poles. Now, instead of having passive access to the sea through the Neva, he faced a full Swedish blockade. The wars were enormously expensive, and the economic devastation was compounded by droughts and plagues. War, famine, and disease drained the Russian countryside of the agricultural workforce that created the vast majority of the country’s economic value, putting great strain on Ivan’s rule.

Rebuffed in the west, Ivan was much more successful in the east. Ivan subjugated Kazan and Astrakhan, two bordering Mongol territories, and thus gained strategic control over the economically valuable Volga and Komi Rivers. Ivan issued a patent to the powerful Strogonov family to develop the newly acquired Siberian lands. The Strogonovs hired Cossacks as a private army to protect their possessions, and sent the Cossacks deeper into Siberia, again, to secure the borders by expanding them.

Although the Strongonovs planned to proclaim themselves the rulers over the Cossack gains, the Cossacks pledged loyalty directly to Ivan in return for reinforcements to continue the drive east, eventually giving Ivan control over most of another river system, the Ob-Irtysh in Siberia.

Moscow as an Empire: More Land with the Same Problems

A detail of a land use map for the USSR, ca. 1960, centered on the area under Russian control in 1584. Note that even in 1960, about half of this land was undeveloped. Solid green areas (heavily forested), stripped green (swampland), yellow (desert), and stripped white (arctic tundra) are largely depopulated and were used for hunting, trapping, and nomadic herding, if at all. The area around Moscow was mixed use (farming, grazing, and forestry). Red, orange, and purple areas were used relatively intensively for agriculture to support larger populations but were, overall, poorly irrigated and faced transport issues to move the food to population centers. Russia would always struggle with poor land quality and inefficient land use. For a larger version, click the map.

By the end of his reign, Ivan had further consolidated Moscow’s control over a massive and growing swath of land that stretched from the Caspian to the Arctic. However, even now, Moscow’s empire still faced the same basic challenges it had when it was the region’s least valuable fort.

Moscow still had no ocean access and thus no access to the valuable trade and communication capabilities that that represented. Further, despite its size, Moscow was still surrounded by a flat landscape with almost no significant geographic defenses. The Urals perhaps represented the best such asset controlled by Moscow – but that old and low mountain rage had certainly not stopped the Mongols from invading from the east. Moscow still saw itself as surrounded by enemies and rivals – many of which Ivan had provoked by his military campaigns to gain ocean access in the west. Mongol clans and the various indigenous tribes in the east were also seen as liabilities to be absorbed.

Lastly, although Moscow’s holdings now included relatively sunny grasslands in the south, these were poorly irrigated and most Russian holdings were still boglands and arctic tundra. Further, Ivan now faced the added challenge of sheer size and ethnic complexity to make developing physical and governing infrastructure more challenging.

The new Tsardom still held the same definite geographic center in Moscow, from whence the empire had exploded. It was still governed by the personality of Moscow’s leader who had driven that growth through ambition and perceived need. Moscow would continue its now-long-standing policies of protecting its borders by continually pushing them outward, sometimes at great cost, and sometimes against all odds and even logic, but always, it seemed, with eventual success. This strategy had allowed Moscow to prosper against all odds and grow rapidly into one of the world’s largest empires and would continue to define Moscow’s tactics.

More GeoHistories

Estonia: From Colonized Land to Independent E-State

Estonia is a mostly flat, small country, two thirds of which is covered by forests and marshlands. Its strategic location on the northern Baltic coast…

Kyrgyzstan: Nomadic Heritage, Modern Ambitions

Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked and highly mountainous country in Central Asia. Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan has faced a complex…

Poland: A Developing Central European Power

Poland joined the European Union in 2004 as part of the EU’s “big bang” of Eastern expansion. This broke the Cold War’s East-West divide and…

Central Asia: Core and Periphery

Central Asia is, by its most common definition, those five “stans” that were formerly Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. However, this has…

10 Obscure Videos of Soviet Moscow from the British Pathé Archive

The organization British Pathé, a creator of newsreels of historical events, digitized their archive of 82,000 documentary videos and released it on YouTube. The 3,500…