Today, over 100 identified ethnic groups exist in Russia, 41 of which are legally recognized as “indigenous small numbered peoples.” While these groups make up only 0.2% of the Russian population (approx. 250,000 people), they are spread, with other ethnic groups, over 2/3 of Russia’s territory. The majority reside in Siberia, the Far North, and the Far East.

Although they speak diverse languages and inhabit different regions, an important quality these groups share is their continued reliance on traditional lifestyles to sustain their livelihoods. Many practice nomadism or semi-nomadism, and animistic religions are common, as is economic dependence on hunting, gathering, fishing, and reindeer herding. Such strong ties to the environment place Russia’s indigenous populations in a precarious position, as the country’s environment continues to change with economic development.

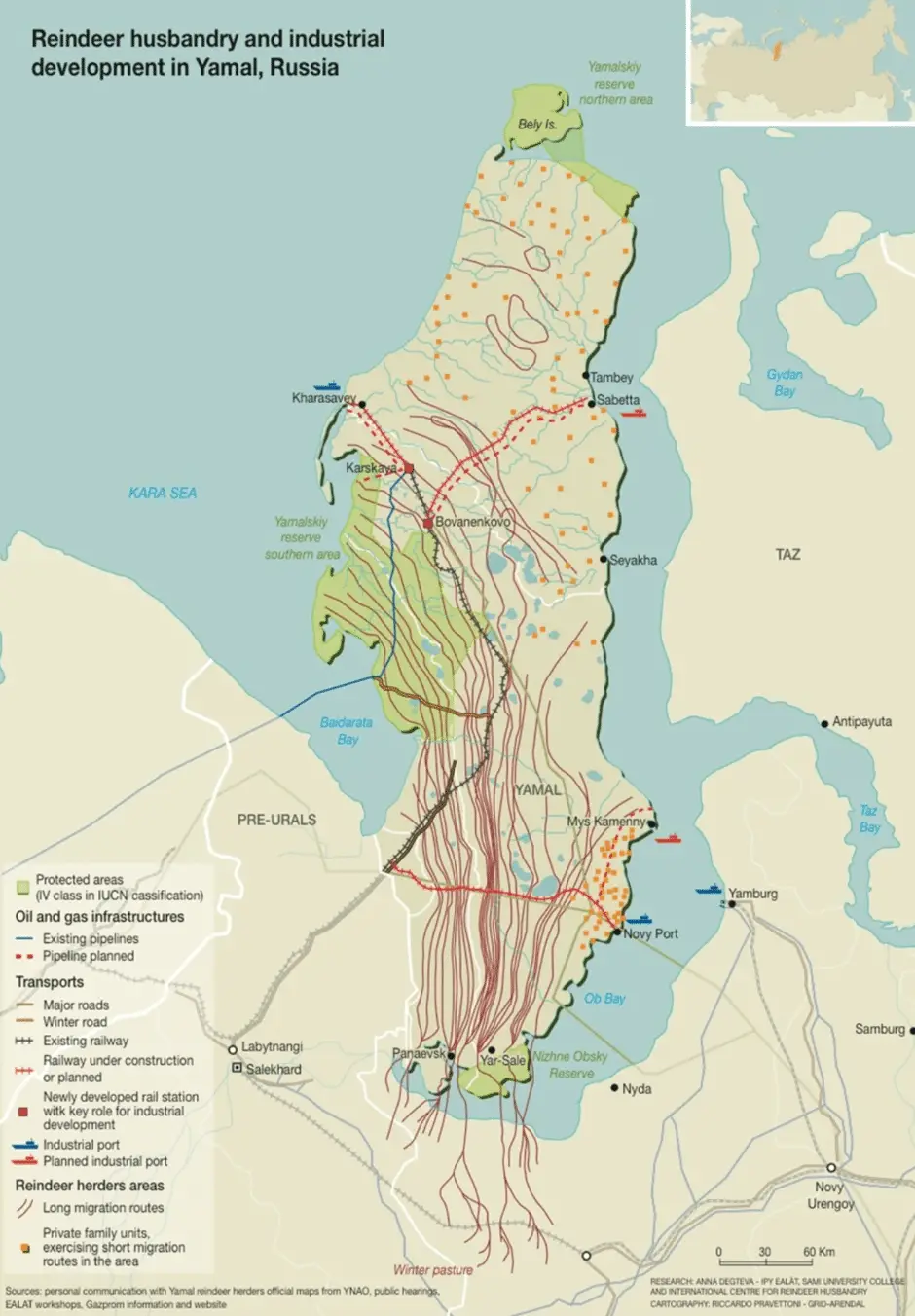

Map of the Yamal Peninsula in Russia.

This article will track the Nentsy, one of Russia’ largest “small numbered” populations, with approximately 44,000 (2010 census) members. They are also residents of one of Russia’s most resource-rich and environmentally sensitive regions, the Yamal Peninsula in Russia’s far north. Using the Nentsy as a case study for understanding a situation facing many “small numbered” populations, we will start by listing ways in which environmental change endangers the Nentsy and then discuss current efforts by the Nentsy and others to protect their rights and livelihoods.

The Effects of Pollution and Development

Environmental change in Russia is a reflection of the country’s long reliance on its natural resources for economic development. The specific resources changed as eras passed, but have included oil and gas, timber supplies, fish, grains, furs, precious metals, and minerals. Wealth supplied by these sources has traditionally driven Russia’s efforts to build infrastructure, fund government programs, and maintain its military. Although environmental awareness has long existed in Russia, it has arguably never played a truly central role in determining the practical direction of Russia’s policies on development.

A map showing the extensive oil and gas fields in the Yamal Peninsula and surrounding area. Detail of map as featured on Harvard WorldMap.

In 2005, oil and gas revenue made up approximately 18.6% of Russia’s industrial profit share, with figures rising to 22.7% by 2013. Most oil and gas is harvested from West Siberia and the Urals-Volga region. The Yamal Peninsula, at the far north of that area, holds one of the world’s largest reserves of natural gas (300 trillion cubic feet, twice the estimated reserves of the United States).

The Nentsy traditional lifestyle revolves around reindeer herding and fishing, nomadism and spiritual practices which rely on the continued existence of sacred sites in nature. While the Nentsy are skilled at adapting to their environment, both the changing landscape and cultural pressure resulting from regional oil and gas development increasingly challenges their survival.

Frequent oil spills are the most notable threats. Reports from Greenpeace Russia indicate Gazprom reports approximately 870 oil spill incidents per year, primarily due to weak extraction infrastructure. Discharges of drilling fluids and drilling muds also release toxic agents into local environments.

Due to the presence of permafrost on the Yamal Peninsula, disruptions to soil quality gives way to changes in drainage pattern and pooling, leading to erosion problems, flooding, and subsequently, disturbed reindeer migration routes. The local hydrology also changes, as ground and surface water are contaminated. In low temperature areas such as the Yamal region, the self-cleaning capacity of many water sources is relatively low. Thus, contamination has the potential to directly threaten both the Nentsy relying on groundwater for drinking, as well as the health and breeding of local fish, such as the white salmon and muksun.

Nenets reindeer husbandry routes and industrial development infrastructure on the Yamal Peninsula. Map as cited in the journal Pastoralism.

Dust created from drilling and related construction can also contaminate drinking water and surrounding vegetation with silica. This reduces plants’ ability to photosynthesize and reproduce, as well as reduces the albedo (whiteness) of snow, which decreases its melt rate. Further, noise flares and traffic in extraction areas have been linked to increased reindeer calf mortality.

Discord also arises from differing cultural concepts surrounding the landscape. Whereas many Western cultures promote land ownership, the Nentsy believe that land should be used by all those on it and practice stewardship in fishing, hunting, and herding. However, while pollution is applying stress to food sources such as fish and reindeer, oil and gas laborers are also competing for fish that are crucial to the herders’ diets in increasingly long summer months.

In terms of spirituality, oil and gas developers often destroy sacred places in favor of quarry pits, railroads, and pipelines, ignoring the Nenets spiritual connection to the surrounding landscape. An example is seen in the Bovanenkovo industrial area, where developers “preserved” a Nenets prayer site using pegs circling six meters around the site, but turned the surrounding area into an industrial excavation.

Following on cultural beliefs, indigenous populations often respond to outside contact with a spirit of co-existence. However, maintaining cultural and physical livelihoods is becoming increasingly difficult amidst environmental change and cultural pressure.

Melting Permafrost in Northern Russia.

Wider climate change is also affecting the Nentsy. In the Yamal region, average temperatures have risen approximately two degrees Celsius over the last 30 years. This has led to an increase in “rain-on-snow” precipitation, which forms large ice covers on the land. This decreases accessible pasture and often forces longer and faster migrations to find accessible pastures. Ecologically, higher levels of precipitation increase shrub height and cover, while simultaneously decreasing lichen cover, an important food source for reindeer. Seasonal climate variation results in later frosts, earlier thaws, and the drying of lakes and wetlands due to evapotranspiration during summer months. While the Nentsy understand environmental change and adaptation as normal facets of the traditional lifestyle, when combined with the impacts of oil and gas development, the challenges of climate-related cultural adaptation are largely amplified.

Change and Response in the Nenets Community

Since the 1990s obshchinas, which are legally recognized indigenous communities, have institutionalized indigenous self-administration and identity building initiatives. Obshchinas provide legal protections for indigenous economic activity, culture, land tenure and self-governance, buffering against displacement and establishing community agency. Yet, despite these protections, the impacts of pollution, climate change, and the overtaxation of resources have led to health problems including malnutrition, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, intestinal infections, and upper respiratory infections within these communities.

Amplifying these challenges are geography and demographics. The Yamal Peninsula, comparable in size to the American state of Mississippi, contains no major cities. Even its capital, Yar-Sale, is a village of just 6,500 people. Modern healthcare is typically delivered through stationary hospitals, which are usually formed in areas with populations large enough to support the heavy investment that modern hospitals require. Supplying nomadic groups with modern healthcare is always a challenge, but supplying it for the Nenets is particularly challenging.

With little to no access to medical care or facilities, indigenous populations cannot rely on obshchina establishments alone. Thus, when adaptation is no longer an option, many populations leave their traditional environment and instead join the sedentary lifestyle, pursuing education and economic opportunities. However, in urban areas, many groups still find it difficult to adapt to life away from the cyclical rhythms of the tundra and continue to suffer the effects of alcoholism and suicide. Moreover, alcoholism and mental health problems commonly arise as a result of physical and spiritual disconnection from the land. Between 2002 and 2012 in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the suicide rate among the Nentsy (primarily those residing in urban areas) was approximately 72.7/100,000 Nentsy per year, as compared to 50.7/100000 non-indigenous peoples per year.

To tackle community challenges, many regional indigenous groups hold annual gatherings in order to discuss community challenges and strengthen solidarity. One such event is being organized in the Yamal region using the Вконтакте community page, “Голос Тундры” . Scheduled for December 2017, the event will discuss the 2016 anthrax epidemic and bring together surrounding communities to celebrate culture and spread awareness of health related challenges.

Wider Responses and Opportunities

Differences in culture, language, and geographic location can disconnect local indigenous populations from effective decision making platforms, marginalizing them politically. Thus, external bodies play an important role in giving them a voice.

Article 69 of the Russian Constitution protects indigenous small numbered peoples. However, the state’s definition of “traditional lifestyle” became rather limiting after the Russian High Court decision in 2009 to exclude cultures which incorporate aspects of “modern achievement,” such as boats and snowmobiles. Additionally, while federal legislation may provide indigenous groups recognition, regional legislative measures do not always correspond. Until recently, protections surrounding industry regulation, reindeer husbandry and fisheries in the Yamal-Nenets region lacked effective implementation. Such gaps in protective measures across different levels of government commonly exclude indigenous populations from meaningful participation in political processes.

Arctic Council International Meeting.

The Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) is currently working with the State Duma and government to defend the legal interests and human rights of 41 indigenous peoples, organizing 35 regional and ethnic organizations over 25 Russian regions. The organization holds a Congress of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and Russian Far East every four years. The congress considers environmental, social, economic, and cultural issues and ways to solve them. Moreover, RAIPON also promotes indigenous interests internationally, as a member of the Arctic Council, the United Nations Economic and Social Council, and the Governing Council Environment Forum of the United Nations, and as a supporter of the Arctic Council’s Sustainable Development Working Group and the Arctic Contaminants Action Program.

While indigenous people face threats from wider economic development, in an age of increasing environmental awareness, private entities are taking action to consider both the environment and indigenous culture when developing new projects. Such an example includes Gazprom’s measure to implement special crossings over utility lines to allow the free migration of reindeer in Nenets herding regions.

Reindeer gathering in Yamalo-Nenets autonomous region.

Additionally, Russia’s growing agricultural industry and appetite for protein are providing alternatives for many indigenous populations. In the coming year, the state plans to allocate 1.771 billion rubles (about 30 million USD) to developing reindeer meat production through agro-industrial complexes in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. Here, venison production is set to increase from around 400 annual tons to 3000 annual tonnes. Such development processes are expected to rely heavily on reindeer herding communities, which will likely expand their voice in the development process.

Indigenous communities such as the Nenets face very real threats from continued economic development and subsequent changes to their environments. Local communities are working to adapt through personal changes and participation in wider activist communities. Public pressure and environmental awareness is also moving private companies to adapt with positive trajectories. However, threats are still present and further work is necessary to make sure that the impact of a changing environment on indigenous groups continues to be recognized and measures are taken to protect indigenous groups’ physical and cultural livelihoods.