In the two decades since its independence from the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan has maintained close ties with Russia, on which it remains economically dependent, while simultaneously reaching out to the West and East. Kyrgyzstan has witnessed two popular revolts and four presidents since independence, and has defined itself as an “island of democracy” in Central Asia. It was the first post-Soviet country to join the World Trade Organization, and until 2014, the only country in the world to host both US and Russian military bases. It also has strong trade relations with China, its neighbor to the east. Next month, in May 2015, Kyrgyzstan is poised to further strengthen ties with Russia, when it becomes the fifth member of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union. Public opinion is divided on accession to the union, which carries economic risks and benefits, and could jeopardize Kyrgyzstan’s relations with other nations, and impact the development of domestic and foreign policy.

Background: History of the Eurasian Economic Union

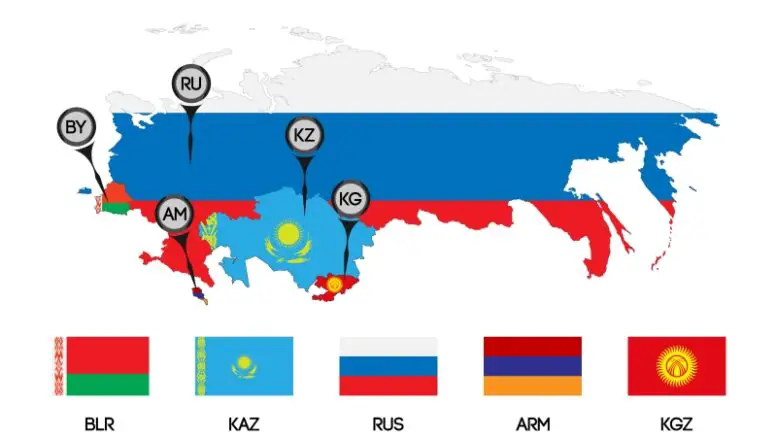

The Eurasian Economic Union, which came into effect in four countries at the beginning of January 2015, is a Russian-led initiative to expand the legislative and geographic scope of Eurasian integration efforts that have been underway since the beginning of the post-Soviet period. In December 1991, the Commonwealth of Independent States was formed of former Soviet Republics. In 1994, Kazakhstan’s first (and, to-date, only) president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, proposed the idea of a “Eurasian Union.” In 1995, Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan signed a customs agreement that became the basis of the Eurasian Economic Community in 2000. The same three countries signed a treaty in 2007 to form the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia (CU) which came into effect in 2010.

In 2012, a Common Economic Space, introducing “free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor” was established between the three countries, overseen by a new Eurasian Economic Commission. The Customs Union and Common Economic Space became the basis of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). An agreement on the EEU was signed in May 2014 by CU members, who entered the EEU in January 2015, along with new member Armenia. Kyrgyzstan will be the fifth member of the EEU, pending ratification of the accession in the Kyrgyz parliament, expected in May 2015.

Putin has compared the EEU to the European Union, and he called the 2014 treaty on its creation “epoch-making.” Many observers see the EEU as a primarily political, rather than an economic project, part of Russia’s effort to maintain influence in the post-Soviet space. Of the CU/EEU’s initial three members, Russia has been most interested in expanding the union. Nazarbayev has consistently maintained that the union is purely economic, and has been more concerned with meeting the union’s standards than with expanding. For Belarus, a smaller economic union – and thus less competition for the Russian market – is in the nation’s interests.

In the fall of 2013, then-president of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych, relented to Russia’s pressure to turn down a deal with the European Union, in favor of closer alignment with Moscow. The decision sparked the Euromaidan movement, and Russia’s subsequent annexation of Crimea. Ukraine’s ultimate rejection of the EEU was damaging to the union, and the ensuing conflict led to the sanctions, dropping oil prices, and collapse of the ruble that landed Russia’s economy in crisis. With the largest economy in the union floundering, and Crimea arguably an illustration of Russian encroachment on national sovereignty, enthusiasm about the EEU waned.

Ukraine has not been Russia’s only disappointment in efforts to expand the EEU. Moldova and Georgia also opted for alignment with the EU via Association Agreements. Armenia planned to move in the same direction until an abrupt change of tack in September 2013, when President Sargsyan of Armenia announced intensions to join the Customs Union instead. The shift has been attributed to pressure from Russia, on whom Armenia’s national security largely depends, especially from arms sales, diplomatic support, and military bases. Armenia became the fourth full member of the EEU on January 2, 2015.

Kyrgyzstan and the CU/EEU – Background

Then-president of Kyrgyzstan, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, sought membership in the Customs Union in 2009, but the political turmoil and public revolt that unseated him in 2010 brought the efforts to a halt. In 2011, then-Prime Minister Almazbek Atambayev requested that the question be revisited. In May 2013 Kyrgyzstan formally applied to join the CU. Parliament adopted a “road map” for accession in May 2014, and in October, Atambayev, now president, announced that Kyrgyzstan would enter the EEU by the end of 2014. Parliament and government adopted the first package of draft laws for accession at the end of 2014, and parliament ratified the creation of the Kyrgyz-Russian Development Fund (KRDF). Atambayev signed an accession agreement in December 2014, and parliament is expected to ratify accession in May 2015.

Since the introduction of the EEU, official rhetoric in Kyrgyzstan has focused on the need for quick accession, in order for Kyrgyzstan to participate in formulating the conditions of the union. Kyrgyzstan’s original “road map” laid out goals relating to technical and sanitary regulations, transport and infrastructure, financial policies, tariff and non-tariff regulations, and customs administration, among other areas. The deadlines for most requirements fell in 2014 or 2015, though some common markets are scheduled to come into effect later, such as oil and gas (2025), energy (2019), and pharmaceuticals (2017).

Russia offered Kyrgyzstan significant financial incentive and support in joining the EEU. Such support is in Russia’s benefit, as it mitigates the concerns of other member countries about Kyrgyzstan’s readiness to participate in the union, while establishing Kyrgyzstan’s loyalty in future EEU decision-making. For Kyrgyzstan, the funding will in theory lessen the initial negative effects of the EEU on the economy. In all, Russia has promised 1.2 billion USD to Kyrgyzstan, 1 billion to be allocated to the KRDF, and 200 million to fund road map efforts. Additional funding has been allocated to help strengthen Kyrgyzstan’s borders. While Kazakhstan and Belarus have been less invested in and committed to Kyrgyzstan’s accession to the CU/EEU, Kazakhstan has also promised $100 million in financial assistance to Kyrgyzstan.

Kyrgyzstan and the CU/EEU – Context

The economic and political contexts in which Kyrgyzstan is joining the EEU are important to note before examining the likely impacts of the economic union in Kyrgyzstan.

Kyrgyzstan’s economy is the smallest of the EEU nations, by a significant margin in the case of the founding nations. The country suffers from a substantial trade imbalance, with 75% of the country’s total trade turnover in 2013 consisting of imports. EEU member countries do not account for more than 40% of the country’s trade. Russia is Kyrgyzstan’s top trade partner overall, accounting for about 25% of imports and 20% of exports. Kazakhstan is Kyrgyzstan’s third largest partner, with about 15% of imports and 12% of exports.

China is Kyrgyzstan’s second most important trade partner. This relationship is heavily imbalanced, with imports accounting for 95% of the total trade. China accounts for 29% of Kyrgyzstan’s imports, but only 3% of exports. A substantial amount of these Chinese imports are then re-exported to neighboring countries.

Kyrgyzstan is less politically centralized than the three founding EEU members. While it experienced, in 2010, the second of two popular revolts to unseat a current president, in 2011 the country peacefully elected its fourth president. It’s parliamentary democracy is still in its formative stages, however: the new 2010 constitution transferred most power from the president to parliament, but decision-making procedures are still being established, and the president maintains power in foreign policy decision making in particular.

At the same time, Kyrgyzstan has been developing its relations with Russia. In 2014, Russian pressure led to the closure of a US airbase in Kyrgyzstan, despite the profitability of the base’s lease for the national budget. Also in 2014, Russian energy company Gazprom boughtKyrgyzstani gas supplier Kyrgyzgaz for a token $1 in addition to assuming the company’s substantial debts. An unexpected crisis followed: Uzbekistan ceased delivery of gas to southern Kyrgyzstan just days later. The region remained without gas until December, when Russia agreed to a deal with Uzbekistan to forgive more than 800 million USD of debt owed to Russia. There were reports that this deal was put forward by Uzbekistan in the spring, but not taken up by Russia until Kyrgyzstan signed an agreement on its entry into the EEU.

Also in 2014, Kyrgyzstan’s parliament introduced two draft laws based on laws already passed in Russia, both of which, opponents argue, would curb democratic freedom. The first, referred to as the “foreign agents” law, which mirrors a similarly named law adopted by Russia in 2012, designates NGOs receiving international funding as “foreign agents.” This makes these organizations, which include those focused on human rights, vulnerable to audit and closure. The second is an anti-LGBT “propaganda” bill, modeled on Russia’s 2013 law but harsher than the Russian version, that would make expressing “a positive attitude toward nontraditional sexual relations” illegal, and punishable by up to a year in prison. Both these laws are still under discussion in parliament. They are seen by some as evidence of direct pressure from Russia on Kyrgyzstan’s politics, and by others as indicating the government’s own interest in shifting closer to Russia politically; either way, Russia’s influence is apparent.

Of course, it should also be mentioned that conservative values have long been a substantial force in Kyrgyzstan. The 2010 revolution unseated President Bakiyev, whom many in Kyrgyzstan saw as the head of a corrupt and nepotistic regime, receiving substantial support from the US. Bakiyev’s opposition, including more conservative political elements, was generally supported by Russia. These forces have now won a more prominent position in the Kyrgyz government thanks to the recent revolution. Thus, both domestic and foreign influences can be seen as guiding the creation of these conservative bills.

Another major factor in relations between Kyrgyzstan and Russia (and, to a lesser degree, Kazakhstan) is migrant labor. There are estimated to be between 300,000 and 700,000 migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan in Russia and Kazakhstan and remittances, according to the World Bank, accounted for 30.8% of the country’s GDP in 2012. These migrants depend on the good will of Russia and Russia is right now tightening its labor and migration legislation, but is maintaining simplified regimes for EEU members, giving added impetus to smaller, poorer countries in the region to seek membership.

Impacts of the EEU in Kyrgyzstan

The following overview of possible economic and political implications of the EEU for Kyrgyzstan is drawn largely from the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung international policy analysis of the accession.

- Economic

In signing on to the EEU, Atambayev assured the nation that his decision was based solely on Kyrgyzstan’s interests. The positive economic impact of the EEU for Kyrgyzstan has been touted by officials as particularly linked to the free flow of labor and goods with member countries. With hundreds of thousands of migrant workers in Russia and Kazakhstan, increased benefits for migrants and the simplified visa and employment requirements would be significant. As far as goods, the EEU opens a 175 million-person market to goods from Kyrgyzstan. This market will also be open to China, via Kyrgyzstan, as officials have emphasized in light of fear of decreased import/re-export from China. Some decline in re-export is inevitable, however. The government has portrayed the expected decrease in re-export and “speculative economy” as a painful but necessary process for the country, whose economy, they say, is too dependent on these sectors.

Hope has also been placed in the road map border security measures. With funding from Russia, these measures may help fortify borders with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and increase the nation’s security. Other preparatory measures for joining the EEU, like higher production and sanitary standards, are specified as benefits as well, making Kyrgyz goods more competitive in regional markets.

Kyrgyzstan’s leaders have also, less-enthusiastically, acknowledged that accession to the EEU carries the benefits of avoiding the risks of not acceding: Prime Minister Otorbaev saidKyrgyzstan has “no alternative,” and Atambayev called joining the union “the lesser of two evils.” The risks of not joining the CU/EEU would likely have included tightened border control for Kyrgyzstan’s exports to EEU countries (including of re-exported Chinese goods), decreased benefits and worse conditions for migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan, higher prices on petroleum from Russia, and discontinued Russian investment in Kyrgyzstan’s energy projects. The extent to which Kyrgyzstan is already economically dependent on Russia makes the EEU a difficult offer to turn down.

While the promise of a 175 million-person economy expands the market for Kyrgyz export, it also expands the competition. Given its size and economy, Kyrgyzstan’s small businesses and farms could have difficulty competing. Customs changes will also affect export: the materials for the production of some major export industries, like the garment industry, come from outside the EEU and will thus be subjected to higher tariffs. In other industries, like agriculture, the promise of easier export may be mitigated by non-tariff barriers on products from Kyrgyzstan.

The need to adjust customs tariffs on goods from outside the CU – Kyrgyzstan’s average import tariff is 5.1%, while the average in the Customs Union is 10.6% – may also affect Kyrgyzstan’s dealings with the World Trade Organization (WTO), of which it is a member. Kyrgyzstan agreed to relatively low import tariffs when it joined the WTO, and an estimated50% of Kyrgyzstan’s duties after adjustment would violate its WTO commitments.

Kyrgyzstan is likely to experience job loss and an estimated 10-12% inflation rate as consequences of joining the EEU. Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Labor announced that unemployment could double as a result of the union, mostly due to closures of bazaars that re-export from China. Job loss and closed businesses could lead to decreased tax revenue, and GDP growth could decrease. Tighter border control with non-member countries will also likely lead to a decrease in imports from countries outside the EEU and thus help limit competition, which could further push up prices and inflation.

In a recent interview, former deputy Begaly Nargozuev pointed out that the economic crisis in Russia complicates the picture for migrant work, since “in just the last months, 58,000 citizens of Kyrgyzstan have lost jobs in Russia and returned [to Kyrgyzstan]. There has been a sharp decline in cash flow coming from migrant workers. The Russian economy has begun to fail from world sanctions, and won’t be able to create new jobs.”

- Political

In integrating with more politically centralized nations, Kyrgyzstan may threaten the progress it has made in democratic development. Its decision-making procedures, not yet fully formed, will be complicated when important decisions are being made outside the country, by a multi-national governing body. Kyrgyzstan’s size, economy, and indebtedness to Russia could make it a weak and easily-influenced player among EEU nations. There is concern that growing economic dependence on Russia will jeopardize Kyrgyzstan’s sovereignty, and, the opposition argues, increase instances of copycat legislation like the “gay propaganda” and “foreign agent” laws.

In joining a union with Russia, Kyrgyzstan is tying itself to Russia’s currently volatile economy, and the fortunes of the EEU itself, which is experiencing its own tensions and instability.

Public Opinion on the EEU in Bishkek

Public support for the CU/EEU in Kyrgyzstan has diminished since 2011 when the question was first seriously raised. The shift has occurred despite the government’s movement towards and promotion of integration. Kyrgyzstan is now divided on the issue, and while there is little visible opposition, there are widespread concerns about inflation, unemployment, and loss of national sovereignty.

In the spring of 2011, an International Republican Institute (IRI) poll conducted throughout Kyrgyzstan reported that 74% of respondents fully or partially approved of joining the CU. By 2013, IRI reported 62% support for joining the CU; this number dropped to 49% in early 2014.

In January 2014, the Reforma Party, a new political party, organized a public protest against accession to the CU. The protests became the movement “Kyrgyzstan Against Customs Union.”

Lawyer Nurbek Toktakunov filed a failed, related court case against the government, appealing the lack of public discussion and the speed of accession. In a recent interview with Central Asia Today, he argued that the government’s decision to integrate was “illegitimate”. The decision, he said, was made by Kyrgyzstan’s politicians, in concert with the Kremlin, “in flagrant violation of the constitutional provision” to provide a platform for public debate. There is now major controversy, he reported, about the impending integration, particularly on social media. The lack of public debate and input constitutes “criminal negligence” on the part of the government, according to Toktakunov: he fears that when the impact of the CU is felt in daily life, opposition could get out of hand, and lead to a “Ukraine scenario.”

In a personal interview conducted for this white paper, Maria, 20, an economics student and social activist in Bishkek, said she thinks financial incentives, as well as pressure, are behind the decision. “Everyone knows our politicians get money from other governments, and their people are the last thing they think about,” she said. “They’re selling everyone else.” Maria also thinks that Russia is pushing conservative legislation in Kyrgyzstan: “Russia wants to create a religious, conservative society here, because it’s easier to control.”

Galina, a 33-year-old student in Bishkek, said the media has played a large role in shaping public opinion here, but she is not convinced by promises of economic benefits: “The media is putting forward the idea that export is good, so if you’re exporting more it’s a good thing. In reality, high quality products will end up going to Russia, and most of what’s produced won’t be available for local people. And our small businesses, farms and companies won’t be able to compete in the larger market.” Most people, said Galina, “don’t understand what the Customs Union will really mean. Older people are hopeful that it will be like the USSR.” In IRI’s 2012 public opinion poll, 69% of respondents over 50 years old said that they would “like the return of the USSR.”

Mira, a 60-year-old accountant in Bishkek, frames accession something like this. “We’ll be like one country,” she said. Her friends, other professional women in her age group, hold contending opinions. “One friend of mine says it will be hard for our country: everything will get more expensive and our economy is too small to raise salaries and pensions along with prices. Another friend says it will be good – Kyrgyzstan is a good place to open a business, and if a lot of new Russian and Kazakh businesses open here, it will create more jobs.”

Mira is hopeful. “I think the Customs Union will improve the country, it will bring our country to life,” she said. “And it will be easier to go to Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan to work.”

Even if the opportunity to work in Russia did arise, said Alina, a 24-year-old teacher in Bishkek, she wouldn’t take it. “I would feel like an immigrant,” she said. “I know people from Central Asia aren’t treated very well there.”

Kyrgyz officials have said that opposition to the EEU is focused on short-term repercussions, which, officials acknowledge, could be challenging. Leaders argue that factors like Kyrgyzstan’s interest in involvement in regional projects and border control and security need to be taken into account. Yulia, a 40-year-old baker, also takes a longer view – though not because she trusts her government. “I think the Customs Union will create a crisis here for a year or two,” she said. “While we adjust, it will be really hard. Prices will rise to match Russia’s but wages won’t. We’ll suffer. But ultimately it will improve the country. Factories will open, everyone will have jobs and pensions. Putin has done a lot of good things for his people. Our government doesn’t think about its people at all. When our laws change to match Russia’s, it will benefit us.”

Conclusion

The Eurasian Economic Union is still in its nascent stages, and its creators – Putin in particular – envision an integrated bloc of nations encompassing the post-Soviet space and beyond. Kyrgyzstan’s experience as an early non-founding member of the union will be telling, and a number of questions are yet to be answered. To what degree will domestic and foreign policy be affected by economic integration with more politically centralized regimes? Will the current government withstand the public’s reaction to the inflation and job loss likely to hit the country early in the integration process? Will Kyrgyzstan’s experience encourage other nations to join the EEU, or will it persuade them to avoid integration – and will they have the choice?