A large part of Russian society, particularly its political elite, still cherishes the great dream of Russia as a powerful and economically strong global player. Against the backdrop of an active foreign policy in recent years, which has brought about some indisputable successes in the international arena for Russian President Vladimir Putin, Russia might seem to have embarked on a trajectory to fulfil this dream. This is underpinned by the social and economic achievements of the years since 1999, during which the Russian economy grew markedly and the social situation stabilised.

However, it is the economy that may prove a weak point in this calculation. In this field, Russia can hardly present any achievements at the moment. A stagnating, if not falling, economy could reverse the gains of recent years and undermine the popularity of the current political regime. Moreover, a country’s standing on the international stage is increasingly dependent on economic performance. It is doubtful whether Moscow is capable of creating the necessary economic foundation to fulfil its global ambitions.

This paper provides a concise overview of Russia’s economy. First, it describes the growth model of the past fifteen years and explains why that model is now exhausted. Secondly, it examines the reaction of the country´s leadership to the stagnating economy. Finally, to evaluate the feasibility of any reform programme, the paper pinpoints the biggest economic problems currently facing Russia with an overview of the main questions relating to Russian modernization. The main problems examined will be those that the Russian economy faced before the current crisis, as these can still be considered fundamental and, as we will see, were actually causing considerable concern even before sanctions were imposed during the Ukrainian crisis and before the current economic crisis began.

I. Golden Years

From 1998-2008, Russia´s economy grew faster than that of the USA, not to mention Germany´s, and its share in the world´s GDP, measured in purchasing power parity, grew from approximately 2.5% to 3.2%.[1] Sergey Aleksashenko, former Russian Deputy Minister of Finance and deputy governor of the central bank, roughly divides these years into three developmental stages in terms of respective growth engines.[2]

The first played out during the 1998 financial crisis. Connected with state default, the crisis brought about a short economic downturn. The crisis did not derail the recovery that had started in 1996 after a period of transformational decline caused by the shift from a planned economy to a market economy. On the contrary, depreciation of the rouble provided a growth engine, boosting the competitiveness of Russian goods in both domestic and foreign markets. Production of food, beverages, tobacco, chemicals, and metals all accelerated, for instance. [3]

In 2000, a new stage and a new engine emerged – companies in the hands of new captains of Russian industry. The initial redistribution of Soviet assets was completed, political and economic upheaval was subsiding, and private owners, certain of their assets, started making large-scale investments. This led to better management and higher labour productivity. Most of these enterprises were concentrated in the extraction of raw materials for export. Russian oil production rose by almost 50% between 2000 and 2005. Smaller, albeit still significant, expansion was achieved in the production of coal, iron ore, steel, aluminium, and copper.[4]

The engine was not so much the exports themselves, supported by rising prices, as the exporting companies´ demand for domestic goods and services. Revenues from oil exports also enabled the Kremlin to launch costly investment projects and raise wages and pensions, which further boosted domestic demand. As a result, manufacturing increased by 9.5% annually between 2003 and 2007.[5] Russian companies often did not have to invest heavily since there was still substantial capacity left from Soviet times.[6] Supported significantly by favourable global conditions,[7] Russia returned to its 1990 GDP level by 2007.[8] With the incarceration of oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky in 2003 and the state takeover of his business, the willingness of Russian entrepreneurs to invest abated.[9] From 2005, the stagnation of real production in the resources sector was masked by rising resource prices. The resource sector’s contribution to Russian growth was, in fact, falling.

Fortunately for Russia, the third growth engine was already emerging – foreign investors had forgotten about their losses from the 1998 crisis and begun returning to Russia. High oil prices and a rapid improvement in sovereign debt ratings made it easy for Russian businesses to take out foreign loans. From 1 January 2005 to 30 June 2008, 400 billion US dollars (hereafter as $) was borrowed. Aleksashenko estimates that about half of this was spent on mergers and acquisitions, and about $55-60 billion a year financed economic growth (on average 4.3% of GDP from 2005 to 2008).[10] This was directed mainly towards non-tradable sectors such as construction, internal trade, and services. These accounted for about 80% of growth from 2005-2007 and almost all growth in 2008.[11] Following the crisis in that year, capital inflows dried up and some investments were withdrawn. Oil prices and the growth engine collapsed as did Russia´s economy.

The post-crisis recovery did not depend on a new growth engine. As in the wake of many economic crises, a statistically dominant growth factor was the rebuilding of inventories. This exhausted itself in 2012. Another contributing factor was a rise in imports and import taxes (VAT and custom duties),[12] enabled by increasing real wages, especially those of state-sector workers, including teachers, doctors, and the military. Growing household debt also played a role to some extent.[13]

II. The Gloom of 2013 and Early 2014

At the beginning of 2014, still some time before the dispute with the West over the Ukrainian crisis, the prospects for the Russian economy were bleak. Over the course of 2013, the IMF, World Bank, the Russian government, and others were lowering growth estimates step by step from 3.2% to the eventual figure of just 1.3%.[14] The economy continued to slow further with no growth in the first quarter of 2014.[15] Although some compared the situation to 2009,[16] this was an exaggeration, since oil prices, which are most important to the Russian economy, were far higher than in 2009. The culprit must have been something else.

Long-term growth estimates were also cut. The Ministry of Economic Development, for instance, expected average annual GDP growth of only 2.5% to 2030.[17] In 2007, President Putin had declared a goal of doubling the GDP by 2020,[18] which would have meant average growth of 6.6% a year. Even after 2010, many remained highly optimistic, including the Ministry of Economic Development, which had previously offered assumptions of annual GDP growth of 3-3.2% between 2013 and 2030 as a pessimistic scenario.[19]

Investment into fixed capital unexpectedly fell by 0.3% in 2013. In spite of preparations for the Sochi Olympic Games, investment fell by as much as 7% in January 2014 compared to January 2013, and this trend continued in February and March, with a fall of 3.5% and 4.3% respectively.[20] In March 2014, the Central Bank raised its key lending rate from 5.5 to 7%, in part as a measure against the already weakening rouble, making new investment more expensive.[21] Unexpected rises in food prices pushed inflation in 2013 to 6.4%, slightly over the Central Bank´s target.[22] In December 2013, business conditions in the Russian manufacturing sector declined at a rate not seen since December 2009. Employment in manufacturing continued shrinking for, with a single exception, 14 consecutive months.[23] Overall manufacturing growth was a mere 0.5% in 2013. Industrial production, including mining and quarrying, performed even worse with only 0.4% growth.[24] During the first quarter of 2014, it improved only marginally by 1.1%.[25]

Consumer activity, strong since 2008, also suffered, with a slump amounting to more than 6% in real prices in November 2013 as compared to November 2012.[26] In the new year of 2014, consumption remained sluggish, especially taking into account growing inflation.

Figure 1 – Buyer Activity Index; January 2008 = 100; Source: Romir[27]- the index is composed in current prices, without inflation

Financial markets were not spared the troubles. The Moscow stock exchange stagnated; from March 2012 to January 2014, while the S&P 500 and EuroStoxx 50 went up by 45% and 31%, respectively, Russia’s MICEX gained a mere 4%. No wonder investors withdrew $500 million from Russia-oriented equity funds in January 2014, thereby prolonging the trend from the previous year, when $3.21 billion had fled.[28] Russia lost a total of $61 billion in private investments in 2013; another $34 billion was withdrawn in January and February 2014.[29] Whereas overall household debt – 14-15% of GDP in 2013 – poses no threat by itself, by February, interest rates had risen to 14%, compared to the 5-7% common in developed economies,[30] meaning a debt-driven consumer demand boost to the economy was already unlikely.

The whole situation was all the more stunning as there were several good reasons for the economy to be running smoothly. Unemployment was low at approximately 5%, compared to 8.3% in 2009. Wages had risen in nominal terms by 12.4% in 2013,[31] meaning that household spending should have boosted growth.[32] Prices for oil and gas, engines of Russia´s exports, stood at historic highs. Some sectors even saw boosted productivity. For instance, parts of the defence industry sector had grown steadily since 2011 by 7.5-14%, in spite of a 10% cut in the workforce. The productivity increase was, however, offset by a 23-25% rise in wages. Moreover, this growth had mostly been paid for by the state so it can hardly be taken as proof of rising competitiveness.[33] In most other sectors, productivity remained a negative issue in 2011-2013.[34]

The economic trouble found its way into public budgets that had to battle with declining revenues and, at the same time, with increasing expenditure. The central government budget recorded virtually no deficit in 2012. Regional budgets did much worse, being burdened with new social obligations Putin had mandated in his re-election campaign but which were not financed at the federal level, sending their deficits up from an expected 32 billion roubles to 278 billion.[35] A year later, the federal budget was also confronted by unexpected problems as revenues dropped owing to muted economic activity. Though the revenues grew by 1.3% in 2013, with inflation as high as 6.4%, the real value of the federal budget´s receipts dropped and the budget ran into deficit.[36]

The Russian budget was also vulnerable concerning expenditure. Having grown in nominal terms by a mere 0.4% in 2003 and 14% and 2004, the increase in expenditure accelerated significantly in 2005 and 2006 to 30% and 22%, respectively, culminating with 40% growth in 2007, the year before the 2008 presidential election. The main driver of this increase was higher social and infrastructure expenditure. The 2008 crisis did not bring about any curtailment as they rose further in 2008 and 2009, by 26% and 27%, respectively. The following years from 2010 to 2013 saw a rather moderate expenditure growth fluctuating between 3.5% and 18%. All in all, central government expenses rose by a factor of 5.5 from 2002 to 2013.[37] This diminished budget surpluses, even though macroeconomic conditions were favourable. According to Andrej Klepach, Deputy Minister of Economic Development, pay raises for state workers, one of Putin´s promises, cannot be implemented unless the economy grows annually by at least 4%. Otherwise, it will constitute “a significant burden on regional budgets and the economy as a whole.” [38] If all Putin´s post-election promises are to be honoured, 7% growth is needed, Klepach warned in December 2013.[39] Further, the government does not appear to be willing to curb planned military spending increases and fears any cuts in long-term obligations could trigger political instability, as pensioners and state workers are the main parts of Putin’s political base.[40]

III. In Search of a New Engine

Even without the sanctions, imposed on the Russian economy by the West, and the steep fall in oil prices the old growth model is exhausted. However, what new model to pursue is not immediately clear. It is clear that several options would likely not work.

The Ministry of Economic Development has stated that “in 2012, the Russian economy shifted to a new growth phase, characterized by slowing investments and consumption against a background of weakening foreign demand” and forecasts that even higher commodity prices would not boost growth by more than 1.5%.[41] With deteriorating faith in the economy, domestic households are unlikely to spend or take up much new debt.[42] The state’s ability to raise wages and spend on infrastructure is also not unlimited. Moreover, doubt exists as to the ability of the Russian state to find sensible investment projects that would really boost the economy, especially when their costs are considered. The Russian economy is also believed to be operating close to full production capacity, which anyway prevents a new round of low-investment consumption-driven growth as has been the case over the last decade.[43] With nothing changed, rising consumption would only mean higher imports and possibly inflation.

While there are a few voices suggesting Russia focus on exporting raw materials primarily to China, the overall consensus among Russian economists and politicians is that a modernization based on innovations and a strong manufacturing sector is the only way for Russia to retain and foster its international standing in the future.[44] Russia is unique among large economies – a country industrialized a long time ago with a manufacturing sector actually unable to compete with either highly developed or developing countries. For the former, Russia’s manufacturing technologies are outdated and for the latter, Russian wages are too high. Russia has almost achieved the GDP per capita level of new European Union members such as Poland and thus has truly departed from the group of countries that focus on mass production of cheap, relatively low-tech products such as China, Turkey, Mexico and India. Russian economist Vladimir Mau describes Russia as being in a “competitiveness trap,” in which relatively high wages exist alongside insufficient institutions. There are two obvious ways out of this “trap” – either to improve the underdeveloped institutions such as courts, which are notoriously incapable of defending property rights, or to lower wages. Most economists and politicians would understandably prefer the first option.[45]

The year 2013 saw quite a few Russian government representatives admit that the resource-based economic model was exhausted. However, to plan for a new growth engine, concrete problems must be named and appropriate policies designed and implemented. A view on these issues shared by most of decision makers is needed. This consensus finding process is hindered by competition between the two informal power groups in the Kremlin. The so-called liberals control the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economic Development, and the Central Bank; Prime Minister (PM) Medvedev is regarded as one of them. This group enjoys the support of some oligarchs such as Viktor Vekselberg and Alisher Usmanov.[46] The other group is often called siloviki (sila means power or strength in Russian) and is chiefly composed of former and current members of the security and intelligence services. The most important representatives of the siloviki are Igor Sechin, the former Deputy PM and current Executive Chairman of the state-owned oil giant Rosneft, and Vladimir Yakunin, the head of the Russian Railways, which is the biggest employer in Russia. This group´s power base lies in the low and middle ranks of the bureaucracy and state-owned companies, many of which are under its direct control.[47] Both groups try to influence President Putin, who acts as a kind of arbiter between them.[48]

The difference in economic policies of these groups revolves around the state’s role in the economy. The liberals push for decreasing state involvement and for reforms to improve the business environment and fight corruption, often warning that slow growth could lead to political turmoil.[49] The siloviki would like the state´s role in the economy to expand (therefore they are sometimes referred to as “statists”), although they do not deny the need for modernization. They would only like it to proceed more slowly and from the top down.[50] Accordingly, they demand that privatization plans be dropped since they believe the state is better equipped than the private sector to generate growth during times of volatility. Simultaneously, they want the central bank to stop being passive and to lower interest rates. The liberals oppose these plans, arguing that the current stagnation is primarily not a result of bad macroeconomic policies but rather limited production capacity and labour force.[51] This view is also held by the World Bank.[52] One of the main representatives of the liberals, German Gref, head of Russia´s largest bank Sberbank, put it bluntly – measures to spur demand, such as printing new money or pumping revenues from oil exports into the economy, will not help; supply-side reforms are needed.[53] The International Monetary Fund also calls for such reforms – including structural reforms and an improvement of the investment climate to, among other things, help reverse Russia’s capital outflow.[54]

As for the Russian heads of state and their relationship towards modernization of the economy, both Putin and Medvedev have spoken about the need to implement according supply-side reforms such as improvement of the business climate, fighting the corruption or increasing the quality of the Russian workforce. Medvedev was particularly fond of the term “modernization” (he used it on average almost 15 times in his State of the Nation speeches in 2008-2011, in comparison to Putin´s average 4 times in the corresponding speeches in 2004-2007 and 2012-2014).[55] Many action programmes have been proposed by the Kremlin; including a plan to make Moscow a global financial centre. However, even Medvedev does not appear to be willing to push hard for the reforms.

VI. Troubles on the Way Forward

The health of 21st century economies is generally measured based on certain criteria, the most important of which are the competitiveness of the marketplace, the strength of human capital, the ability to develop and finance innovations (creating need for a functioning financial sector), and diversification with the ability to create products and services of high added value.[56]

- The State´s Role in the Economy

Even twenty years after the collapse of the USSR, Russia’s economy is dominated by state-owned giants. State dominance is generally understood to discourage competition by allowing some economic actors to operate with preferences and to generally discourage innovation by adding bureaucracy with little inclination to take any risk. Up to half of the Russian economy is estimated to be directly controlled by the state, with significant presence in transport (73% in 2013), banking (49% in 2013), oil and gas production (40-45% in 2013), communications (14% in 2012), and electricity, water, and gas distribution (26% in 2012). In terms of value, the share of state-owned firms in the RTS equity index was 51% in 2013, a small improvement on 66% in 2007.[57]

In May 2012, the re-elected President Putin signed a decree stipulating privatization of all state holdings in companies outside the energy and defence sectors.[58] That offered hope that large-scale privatization, which had brought state coffers $111 billion from 1995-2012, would continue. According to the plan, about $66 billion (by January 2014 exchange rates) spread across as many as a thousand companies was to be privatized between 2013 and 2016.[59] However, the plans have been slow to materialize.

Political struggles between the siloviki and liberals are likely a major factor in this.[60]

Moreover, a clear privatization plan is missing. Up to a point, the managements of the companies decide themselves and they mostly oppose privatization.[61] Contrary to the aforementioned privatization decree signed by Putin, the Russian government is unlikely to release its grip on the financial sector, retaining majority stakes in Sberbank and VTB, the two banks with biggest assets.[62] Whereas in the summer 2013 the Ministry of Economic Development expected the state’s share in the economy to drop to 20% by 2018, First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov in January 2014 saw the share dropping to “no more than 25%” by as late as 2020.[63]

The state’s share may actually expand. The Russian state-controlled oil major Rosneft bought the private oil company TNK-BP in the spring 2013. Although this could be interpreted as partial privatization, as BP gained an 18.5% stake in Rosneft, the controlling share is still in the state’s hands. Further, in an effort to fight tax fraud, the Russian Central Bank has withdrawn licences from several smaller, private banks. The sector will indisputably benefit from some consolidation. However, depositors are expected to move their savings to banks considered to be larger and safer, most of which are state-held.

The government is currently trying to mandate improved efficiency from state companies. For instance, state corporations such as Gazprom or Russian Railways will not be allowed to raise their tariffs over the inflation levels of the preceding year. As inflation is now expected to grow, these corporations will theoretically have to pursue cost-cutting measures if they wish to maintain even current revenue levels. This rule should guarantee a certain level of predictability regarding prices charged by the monopolies, which should help the economy overall. In addition, state companies will be obligated to enhance their productivity by adhering to other government-set targets such as market value or return on investment.[64]

The state also dominates employment. Real wage growth has been mainly fuelled by increasing state sector salaries. In 2011 and 2012, the average nominal wage of state-workers increased by 28%, whereas in the economy as a whole it increased by only 14%.[65] In 2013 state-workers reportedly brought home 13% more in real terms, while the average real wage grew by just 5%.[66] Russia, a country of 140 million people, has an astonishing 20-million strong army of state employees, accounting for 25.7% of the economically active population in 2012. A year before it was only 24.9% and in 2009 even less (24.6%).[67] Thus, the state workforce grew by 1.1 million jobs from 2008 to 2012, while the private sector shrank by 300,000 jobs.[68] Sergei Beliakov, Deputy Economic Development Minister, commented on this as follows: “People want to work either for large state companies or become a government official, which means they do not see an opportunity to make money based on their own actions or potential. The government demotivates society and creates an environment where it is easier to be part of the distribution system rather than develop one’s own entrepreneurial spirit.”[69]

Rising numbers of state employees at a time of low unemployment and a still growing economy is rather unusual (hiring in the state sector is a common anti-crisis measure). Private companies are, thus, forced into competition with state companies not only over contracts but increasingly also over labour force.[70] New investments are more difficult to staff and only drive competition for workforce further, leading to even higher wages. As increased labour productivity has not materialized, Russian companies have been made less competitive.[71] We can see that rising wages and a depleted labour force caused by an aging society (see below), both of which negatively affect Russian business, are being worsened by state actions.

- Demography and the Labour Market

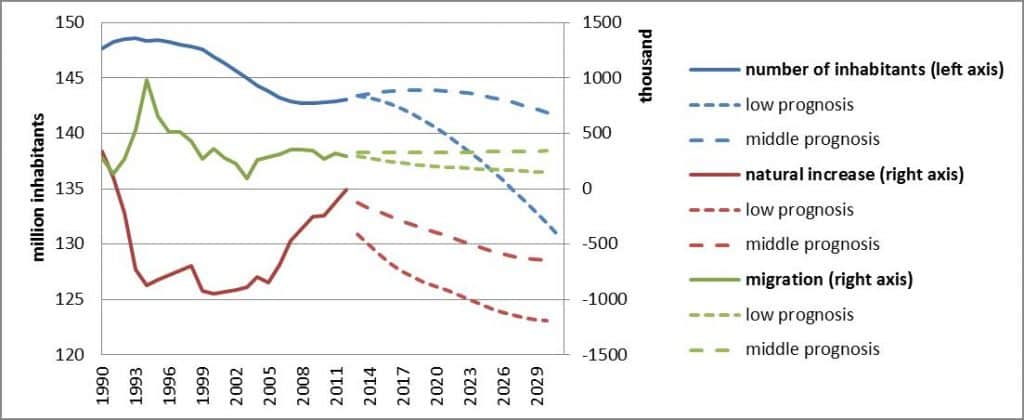

Although unemployment is now forecast to grow with the current crisis,[72] Russia may still suffer adverse effects in the future due to its demography. Russia and the other former Soviet states are unique in terms of demography – a low fertility similar to that of the West is combined with the high mortality common in the Third World. There was not a single year between 1992 and 2011 when there was not a natural population decrease – see Figure 2. The loss of 12 million inhabitants (almost 9% of the 1992 population) was to some extent offset by the immigration of 8 million people. The total population loss is, therefore, not so large and might not cause any severe problems in the short term. The age structure poses a far greater risk. In 1989, 84 million people of an economically active age lived on the territory of present-day Russia making up 57% of the whole population. By 2002, this figure rose to 89 million, 61.5% of the total population. Ten years later, though, the share of the economically active population shrunk by 1.5 percentage points, in absolute terms by 2 million.[73] And this trend is expected to get much worse.

Figure 2 – Russian population since 1990 and projection through 2030; source: Federal State Statistics Service[74]

The Russian statistics office works with three future scenarios – high, middle and low. The high scenario, based on a de-facto zero natural loss and immigration rising from the current annual level of 300,000 to half a million immigrants by 2030, appears very unlikely, especially with the current economic woes.[75] Apart from sustaining a zero-level of natural loss, it is highly doubtful that Russia can attract enough foreign workers and, even if it could, whether it would help much. Firstly, it is questionable whether even in Central Asia, the traditional foreign workforce reservoir for Russia, there are so many labourers willing to move to Russia. Secondly, it is far from clear whether such an influx of immigrants could be integrated easily. Large numbers of foreign workers create inevitable frictions with the domestic population and strengthen xenophobic sentiments already present in Russian society. Thirdly, even if Russia succeeded in attracting sufficient numbers, they would mostly be low-skilled people too poor to invest much into raising their qualifications.[76] Productivity would, therefore, remain low and the contribution to the Russian economy very limited. Finally, many immigrants tend to send a great part of their earnings home and thus do not increase Russian domestic consumption by much.

A high level of immigration seems unlikely. Further, age groups born during the 1990s are entering reproductive age. The politically and economically uncertain 1990s saw a collapse in births, so this age group is small. It cannot be expected, if current fertility rates of 1.7 are maintained, to produce enough children to even reproduce themselves, let alone to stop the looming demographic contraction. For these reasons, the middle and low scenarios of Russia´s population development seem more probable. Figure 2 depicts their parameters. The number of population at the economically active age is forecast to drop by 8-9.5 million by 2023 (to 54-55% of the total population).[77] Raising the pension age may help. However, this is a politically sensitive issue and the Russian leadership has ruled out this step so far. Olga Golodec, deputy prime mister for social affairs, said in January 2014 that this question “is closed for the next ten years.”[78] The current recession may change this too, though.[79]

Outside of state influences, Russian businessmen have rated employee job commitment and readiness, as well as labour-related habits and discipline as larger problems than corruption, taxes, or bad institutions.[80] Prime Minster Medvedev has announced reforms aimed at increasing the quality and mobility of the workforce.[81] However, the new state budget does not indicate any commitment to anything like this. For instance, expenditure on education was, even before the current crisis, set to fall by 12.9% in 2014, healthcare was also due for a cut of 8.6% and housing and communal services were due to be cut by 23.7%.[82]

- Diversification – Dominant Resources, Weak Manufacturing

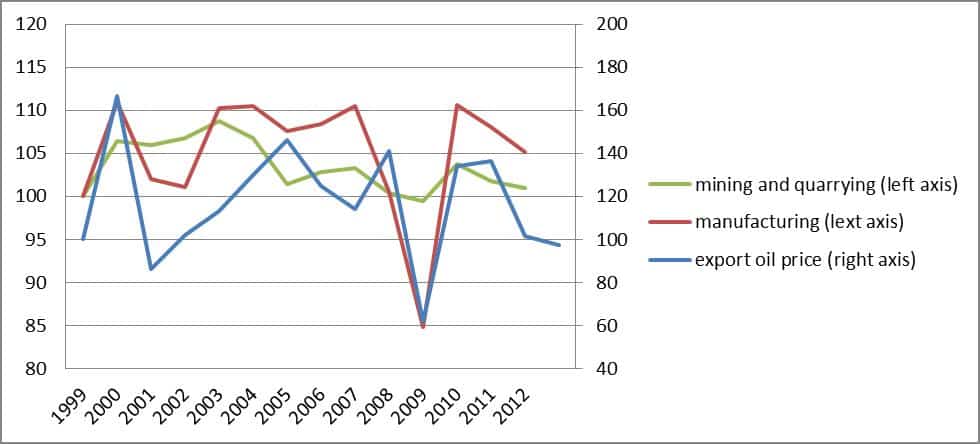

Since approximately 2006 the natural resources sector has no longer been the main growth engine. In spite of this, it remains a pillar the Russian economy rests upon, accounting for approximately 25% of GDP while manufacturing accounts for a mere 2.5%.[83] Furthermore, manufacturing seems to perform in sync with oil prices – see Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Manufacturing, mining and quarrying (including oil and gas production) and oil prices – year-on-year change in % – Source: Federal State Statistics Service [84]

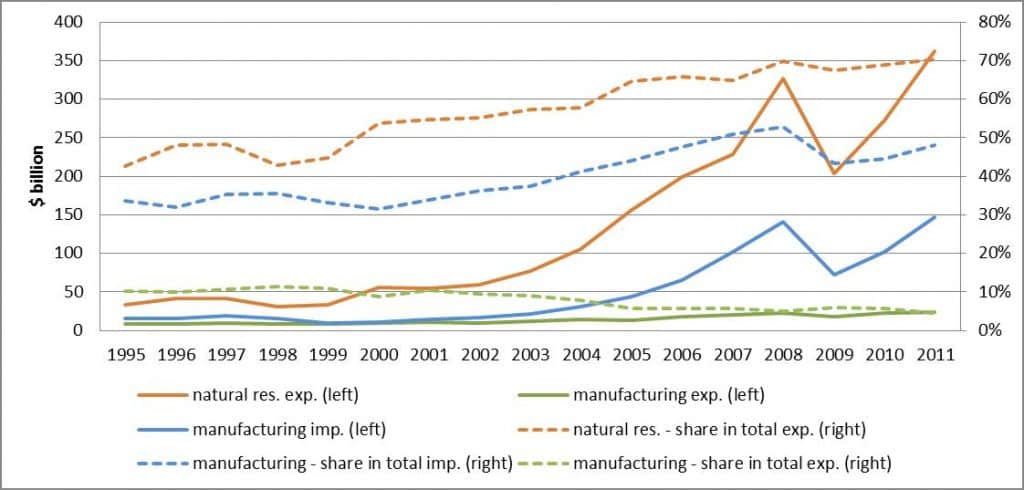

The natural resources sector also dominates foreign trade and, again, crowds out manufacturing. In 1995, the sector’s share was 42.5%. By 2011, it reached 70.3%. At the same time, Russia managed to export more manufactured goods in absolute terms – a rise from $8 billion to $23 billion. However, manufacturing’s share in exports sank from 10.2% to 4.5%. In contrast, imported manufactured goods make up 48% of all imports, whereas they accounted for only a third in 1995 – see Figure 4. The balance of trade has remained positive, although the surplus has been steadily declining from 23% of GDP in 2000 to 10-11% of GDP by 2010-2011. Without oil and gas exports, the trade balance would have been in deep deficit – minus 7.5-8% of GDP in 2010-2013.[85]

Figure 4 – Exports and imports of natural resources and manufactured goods – Source: Federal State Statistics Service [86]

Too large a dependency on the resources sector presents dangers for the wider economy. One of them is in the balance of trade. If oil and gas pri ces stabilize, let alone fall, the surplus of the current account (combining trade in goods and services as well as income transfers from abroad) starts to shrink quickly. Thus, with falling oil prices, as soon as the current account surplus drops under one percent of GDP, a severe financial crisis and rouble devaluation are all but unavoidable. In early 2012, in spite of the then fairly high oil prices, Aleksashenko predicted this scenario could unfold in as soon as five or six quarters, depending on the rise in imports. However, should the oil price fall by $10-20, the situation would worsen very rapidly, he added.[87]

Imports were not rising as quickly in 2012 and 2013 as between 2009 and 2011,[88] so there was no significant weakening of the rouble in those years. Then in the summer of 2014, just as oil prices suddenly took a nosedive, which was accompanied by accelerating capital outflows from Russia, so did the value of the rouble, despite the Central Bank spending a quarter of its foreign currency reserves in 2014 to defend the domestic currency.[89] With an import-heavy economy, Russia now faces the prospect of massive inflation, which is likely to adversely affect many economic sectors, particularly as the Central Bank raises interest rates partially as an anti-inflation measure (another concern being the plummeting rouble).

Another problem caused by the strong link between Russia’s currency and massive oil and gas exports is the strengthening rouble in real terms since the beginning of this century. From 2000 to the end of 2013, the value of the rouble increased by 119% in real terms as a result of high energy prices and growing energy exports.[90] This made it hard for other economic sectors, in particular manufacturing, to compete with foreign competitors (this phenomenon is often referred to as Dutch disease).

The state budget depends on the gas and oil sectors, too. These sectors accounted for approximately half of all federal revenue from 2011-2014, and they continue to gain share. The deficits would have often reached slightly over 10% of GDP without this income. It is an improvement compared to the correspnding figure of 13.5% of GDP in 2009 but it is still much more than 2.5-3.5% in the years prior to 2008.[91] Pre-crisis budget plans forecast dependency on oil and gas revenues decreasing to 43% by 2016, and the deficit without this income source dropping to 8.4% of GDP.[92] However, whereas it was possible to balance the state budget at an oil price of $20 per barrel in 2005, $103 per barrel was needed to do so in 2013.[93] Current economic realities have meant that the government will have to completely redraw budget plans. With defence expenditures off-limits, social programs may feel the bite, even though politicians still deny this.[94]

- Business Environment

Although it has long been a government priority, the Russian business and investment climate remains far behind that of developed countries. In 2013 Russia achieved some success in this field when it moved up 19 places in the annual World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index to the 92nd position (four places ahead of China) out of 189 included countries.[95] However, the report does not include corruption because the World Bank only tries to assess the related legislation and not the phenomenon itself.[96] In the Corruption Perception Index by Transparency International, Russia ranked 127th out of 177 evaluated countries.[97] Even Russia´s billionaires increasingly complain about bribery (as well as a hostile business environment).[98] So, there may be some progress on paper, but it does not appear to have materialized on the ground.

Similarly, Russia´s boost in Bloomberg’s “Best Countries for Doing Business 2014” from 56th to 44th place was tainted by the fact that all the other BRICS countries did even better, some of them by a wide margin.[99] The Index of Economic Freedom, composed by the Heritage Foundation, includes corruption and ranks Russia the 140th freest economy out of 178 countries. Its economy is “mostly unfree” and narrowly escapes being termed “repressed.” The report praises improvement in four “economic liberties” of the ten measured (e.g. in government spending), however, three others, fiscal freedom, trade freedom, and especially freedom from corruption (149th place) have been deteriorating.[100]

Taxes are also still a problem. On the one hand, the overall situation is not so bad with Russia being placed the 56th best country in the Paying Taxes survey by consultant PwC after the government streamlined the taxation process.[101] On the other hand, the state still levies too great a tax burden on small and medium-sized companies, taking 50.7% of their profit (the global average is 43.1%). In this respect, Russia is placed 143rd. As a serious shortfall in budget revenues loomed in the summer 2013, the Russian government mooted plans to raise the tax burden further. These plans were dropped in the end and in their stead a tax reduction is now in the cards.[102] How the current rapid deterioration of the Russian economy will affect these plans remains to be seen.

In September 2013, well before the crisis, Medvedev admitted the plans to improve the business environment were being implemented at a slowing rate. Out of a total of 173 measures that were supposed to have been fulfilled by that time, only 84 actually were.[103] The implementation of the declared reforms will rely heavily on state institutions and they will be under close scrutiny. Most recent President Putin himself has called for an improvement in the quality of state institutions.[104]

- Investment Climate and Financial Sector

Investment levels of 25-30% of GDP are considered ideal for a developing economy, yet the figure is no higher than 21-22% of GDP in Russia.[105] This is an improvement from 15% in 2000 but still less than levels in the USSR, let alone in present-day China.[106] According to a 2013 survey by the Gaidar Institute, 43% of businesses said they kept investment levels static, and another 33% invested less than in the previous year.[107]

Russia’s dysfunctional financial sector, which is not capable of channelling surplus savings to small and medium-sized companies, also contributes to its poor investment levels.[108] On the one hand, some Russian companies send their savings abroad and only 55% of individual Russians keep bank accounts, in contrast to 96% in Europe.[109] On the other hand, Russian businesses complain about a lack of cheap credit and short lending periods. Accessible loans last only three years at most. For example, the technology in manufacturing changes substantially every seven years so Russian manufacturers are unable to get credit with a repayment period allowing for production modernization.[110]

Foreign capital is not helping, either, since it has been leaving Russia over the past few years and will likely continue to do so with sanctions risks and the current crisis. At the outbreak of the 2008-2009 crisis, Russia lost not only three quarters of foreign portfolio-investment, but also 60% of foreign direct investment, which is by nature less speculative.[111] Investing into companies outside the mining and financial sectors is proving hard as the corresponding securities are missing. So, when even Western markets were stabilizing and promising good returns, Russia had nothing to offer.

The importance of investment for re-starting the economy is fully understood by the country´s leadership and has recently been stressed by the World Bank.[112] In September 2013 the Economic Development Ministry estimated that investment activity will be the sole growth engine in the following three years, based on possible improvements to the business environment that would encourage Russian businesses to borrow more and invest in the quality of their production, which will then partially replace imports. [113]

It is anything but clear if current conditions will help these hopes come true. The weaker rouble caused by low oil prices and Western-imposed sanctions will certainly benefit the domestic production and business as happened in the aftermath of the 1998 crisis. This may be, however, cancelled out by lack of accessible funding as a result of the sanctions targeted at funding of the Russian financial sector and the restrictively high interest rates recently adopted by the Central Bank.[114]

In January 2013 as Russia’s statistics office reported a decline in investment activity, an idea emerged that the lacking cheap credit could be supplied by commercial banks. Though the biggest banks are to a large extent owned by the government, their management disliked this proposal. They would rather have ceased lending altogether.[115] To their relief, the idea was abandoned, but it is, nevertheless, a very telling proof of how desperate a situation the Russian government found itself to be in even before the crisis. It remains an open question whether the drop in investment during 2013 could have been revived only by providing more favourable credit to the private sector. A decline of state-funded investment was probably the main reason behind the declining investment activity.[116]

Another interesting debate has started over the National Welfare Fund, in which some oil and gas revenues is accumulated (3.1 trillion roubles or $87 billion as of 1st March 2014). The Economic Development Ministry is in favour of the re-allocation in new infrastructure projects while the Ministry of Finance would rather adhere to the current policy, whereby the money is invested into safe long-term securities in order to be later used for supporting the pension system. Evsej Gurvich, head of a think tank that advises the Finance Ministry, warned that for the fund to fulfil its role, there must be some return on its assets, which would not be the case with infrastructure investments. However, he did not dispute the fact that the new projects could be beneficial to the Russian economy at large.[117]

In November 2013, Putin confirmed a prior decision to invest 450 billion roubles ($13.8 billion, by January 2014 exchange rates) from the National Welfare Fund into three infrastructure projects. Later, the sum was raised to 600 billion roubles (all in all $18.3 billion).[118] On the other hand, some commentators wanted the limit on what percentage of the fund can be used on domestic projects to be raised from 40% to 50-60%; Putin did not allow that.[119] By doing so, Putin positioned himself halfway between the fiscal conservatives and supporters of large state investments. Nonetheless, the adopted decision could be, on the whole, regarded as a victory for the latter since it clearly showed the ease of abandoning conservative fiscal principles. These budgetary principles were further undermined by earmarking as much as $10 billion from the fund for a loan to Ukraine in order to secure the loyalty of the Yanukovych regime.[120] The profitability and enforceability of such a loan were anything but certain. Similarly, Minister of Finance Siluanov raised the idea of tapping the Reserve Fund, another oil fund, to balance the state budget.[121] Such a transfer would have, again, violated the fund´s mission, which is to support the federal budget at times of low oil prices, which was then not the case. As the current crisis unfolds, plans for how to tap both the funds abound.[122]

- Innovation Capacity

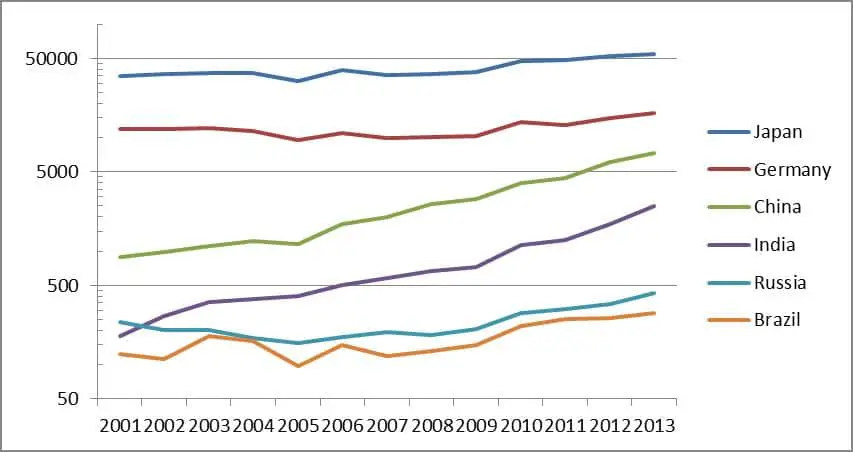

With the exception of the defence and space industries, Russia offers few high-tech products. Despite many attempts to create these, such as with Yota smartphones or the now-shelved Yo-Mobile hybrid car, Russian businesses have not managed to make inroads into foreign high-tech product markets.[123] Moreover, Russian industry is often not even able to satisfy domestic demand. Last year, for instance, lower import custom duties were considered for regional passenger planes since the Russian manufacturing giant, Rostekh, lacked the capacity to meet demand.[124] Further, Russia not only trails behind developed countries in patents granted by the US Patent and Trademark Office, it is also losing ground to the other BRICS members – see Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office – logarithmic scale – Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office [125]

While Russia can claim 6% of the world´s population with a postsecondary education, over the past ten years, Russia has received only 0.24% of all patents granted to non-Americans.[126] Also, Russia´s share in the world´s high-tech production market is minuscule – just 0.3% compared to 39% for the USA and Japan´s 30%. Less than a tenth of Russian enterprises produce innovations, whereas this figure is as high as two thirds in Germany[127] and was approximately 50% for the USSR.[128] In manufacturing, productivity is believed to be up to eight times lower in comparison to foreign competition.[129] Apart from the space and defence industries, the Russian manufacturing sector survives only thanks to demand from within the FSU. Only one in twenty Russian manufacturing businesses is reputedly able to export to the world market.[130]

VII. Conclusion – Russia´s Modernization Dilemma

Even before sanctions and the current crisis, the Russian economy was facing a great many difficult problems: the state´s dominance in the economy; the adverse demographic situation and an ineffective labour market; a huge resources sector; a hostile business environment; a difficult investment climate; and resulting technological backwardness of Russian companies. Replacing the exhausted growth model of the past fifteen years requires deep supply-side reforms and a wide-ranging modernization of the economy.

A question of the utmost importance is who is going to drive this modernization process. The Russian economist Vladimir Mau detects a lack of enthusiasm for the process in Russia that, paradoxically, can be partially traced back to the socio-economic success of the previous decade – the relative social stability and the cushion against economic disturbances in the form of oil funds.[131] The current crisis, however, will be much harder to ignore.

Evgenij Iasin, a Russian economist and the Minister for the Economy between 1994 and 1997, and his colleagues ask if a potential modernization coalition, consisting of “new bureaucracy” and “new business,” will not succumb to the temptations of the current system of controlling the state and the economy. Instead of focusing on productive activities, these groups could orient towards redistribution strategies.[132] A modernization project could receive support from Russian oligarchs, although this is sometimes disputed since they are actually a part of the present system.[133] The status quo is also supported by a large number of Russians who are directly reliant on the state budget. In addition to a quarter of the workforce, there are 40 million pensioners. These two groups together make up 40% of the population.[134]

Other questions also remain unresolved, for instance, whether a return to a higher degree of federalization could help.[135] Consideration is also given to whether present-day Russia, dominated by the resources sector, is capable of modernization and a shift to an intensive growth model (the USSR was notoriously incapable of such a switch). Social stratifications between Russia’s major cities and its countryside could also hinder the process by making it impossible to maintain social stability and cohesion, one of the government’s priorities. These would inevitably come under strain during a major reform process.[136]

Similarly unresolved is the matter of what role the current political elite will play if there is a serious modernization attempt. Mau takes the view that “the state (its highest leadership) is politically interested in modernization” and tries “to encourage modernization and innovation through state corporations and institutions.” Yet, without a real demand for modernization from economic actors, this effort cannot bear fruit.[137] Contrary to this opinion, Aleksashenko thinks that one of the major obstacles to modernization is actually Putin and his closest advisors, who fear a loss of power as a consequence of reform measures.[138]

The Russian historian Vitalij Fomin paints a somewhat more complicated picture. The current political elite are well aware of the need for economic modernization but they are not willing to modernize the political institutions and society. The more liberal Prime Minister Medvedev maintains that changes to the political system will spontaneously occur after successful economic modernization.[139] Alas, Fomin sees two problems in this regard. Firstly and contrary to Medvedev, economic modernization cannot be successful, in his opinion, without first restructuring the political institutions, as these create the environment in which an economy operates. Secondly, “modernization” is understood by the Russian population, in contrast to the political class, chiefly as a reform of Russian politics and society.[140] When the decision-makers and the population are thinking of modernization in such different ways, can it succeed at all?

Concerning the role of the current political leadership, another interesting question arises: to what extent their attitude towards modernization is influenced by the fact that when the Russian economy was flourishing after the turn of the century, the state´s role in the economy was growing. This experience, strengthened by the economic turmoil resulting from the liberalisation in the 1990s, could lead to resistance to any modernization attempt based on economic liberalization and privatization even – or perhaps especially – during a major crisis such the one Russia is currently facing.

Bibliography

ALEKSASHENKO, Sergey, 2012. “Russia’s economic agenda to 2020”, International Affairs 88:1 (2012).

AMOS, Howard, 2015. “Russian Central Bank Set to Keep Growth-Stifling 17% Rate”, The Moscow Times (January 29, 2015), Online, last accessed February 16, 2015.

BBC, 2013. “Ekonomika Rossii v 2014-om: tri neveselykh scenariia” (Russian Economy in 2014: Three Unhappy Scenarios), BBC-Russkaia sluzhba (December 31, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

BBC, 2014. “Rossiia ukrepit sviazi s Aziej, no eto ne budet mest´iu ES“ (Russia to Strengthen Ties With Asia, but not as Revenge on EU) (September 19, 2014), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

BBC, 2015. “Pressa Rosii: Moskva vziala kurs na samoizoljaciiu? – Pensionnyj vozrast opiat´ na slukhu“ (Russian Press: Moscow Aiming At Self-Isolation? – Retirement Age Under Discussion Again) (January 30, 2015), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

BIDDER, Benjamin, 2012. “Potjomkinsche Fabriken“ (Potemkin´s Factories), Der Spiegel, no. 48 (2012).

BIDDER, Benjamin, 2014. “Russland in der Krise: Die Wirtschaft ist Putins Achillesferse“ (Russia in Crisis: Economy is Putin´s Achilles Heel), Spiegel-online (January 1, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

BULIN, Dmitrij, 2013 (A). “Zachem nuzhna novaia privatizaciia v Rossii?” (Why is New Privatization Necessary in Russia?), BBC-russkaia sluzhba (June 29, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

BULIN, Dmitrij, 2013 (B). “Novyj biudzhet Rossii” (New Russian Budget), BBC-russkaia sluzhba (October 25, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

BULIN, Dmitrij, 2014. “Gajdarovskij forum: ministry posporili o pensiiakh“ (Gaidar Forum: Ministers Argued Over Pensions), BBC-Russkaia sluzhba (January 17, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

CLOVER, Charles, 2013. “Russia slowdown challenges liberal wisdom”, Financial Times, (April 17, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

EBERSTADT, Nicholas, 2011. “The Dying Bear”, Foreign Affairs, no. 6 (2011).

ECONOMIC EXPERT GROUP, 2004-2015.[141] “Obzor ekonomicheskikh pokazatelej”, various reports from 2004 to 2015, Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

ECONOMIST, The, 2013 (A). “The S Word“ (November 9, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

ECONOMIST, The, 2013 (B). “To privatise or not to privatise” (January 19, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

ECONOMIST, The, 2013 (C). “Sputtering“ (June 22, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

ECONOMIST, The, 2014. “Sochi or bust” (January 30, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

EDOVINA, Tatiana, 2013. “Uluchshenije investklimata v RF ne pospevajet za grafikom“ (Business Climate Improvement in Russia Behind Schedule), Kommersant (September 23, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

FISH, Isaac Stone, 2013. “Someone Tell the World Bank About Corruption in Russia”, Foreign Policy (October 29, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

FORBES, 2013. “MER priznal nevypolnimym ispolnenie socialnykh majskikh ukazov“ (Ministry of Economic Development: May Decrees Impossible to Fulfil), Forbes (December 3, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

FORTESCUE, Stephen, 2012. “(Ohn-)Macht?” (Power(less)?), Osteuropa, no. 6-8 (2012).

GAJDAEV, Vitalij, 2014. “ Poteriannyj Janvar” (Lost January), Kommersant (February 3, 2014), Online.

GERHARDT, Wolfgang, et al., 2012. “Spaltungen – Editorial” (Cleavages – Editorial), Osteuropa, no. 6-8 (2012).

GRIGOREV, L., et al, 2008. “Postkrizisnaia struktura ekonomiki i formirovanie koalicij dlia inovacij“ (Post-Crisis Structure and Forming a New Innovation Coalition), Voprosy ekonomiki, no. 4 (2008).

HOLODNY, Elena, 2015. “Russia’s Migrant Workforce Is Dwindling”, Business Insider (January 8, 2015), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

IASIN, E., et. al, 2013. “Sostoitsia li novaia model ekonomicheskogo rosta v Rossii ?” (Is There a New Economic Growth Model in Russia?), Voprosy ekonomiki, no. 5 (2013).

IMF, 2013. “World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013”, Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

KELLY, Lidia; KORSUNSKAYA, Darya, 2013. “In blow to Putin, Russia slashes long-term growth forecast“, Reuters (November 7, 2013), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

KOMMERSANT, 2013. “Neplatezhesposobnyj spros” (Insolvent Demand) (December 23, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

KOMMERSANT, 2014 (A). “Vladimir Putin: dlja uluchsheniia delovogo klimata“ (Vladimir Putin: For Business Climate Improvement) (October 10, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

KOMMERSANT, 2014 (B). “Dmitrij Medvedev dopuskaet vozmozhnosti snizheniia nekotorykh nalogov“ (Dmitrij Medvedev Can Imagine Some Taxes Go Down) (December 13, 2014), Online, accessed February 16, 2014.

KRAVCHENKO, Stepan; ROSE, Scott, 2013. “Russia Forecasts Losing Ground in Global Economy by 2030”, Bloomberg (November 7, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

KUZNECOVA, Elizabeta, 2013. “Aviakompanii predpochli import samoljetov“ (Airlines Prefer Importing Planes), Kommersant (November 7, 2013), at www.kommersant.ru/doc/2337354, accessed November 10, 2014.

LABINSKAIA, I., 2011. “Rossiia – obshschestvo riskov-2“ (Russia – Society of Risk-2), Mirovaia ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniia, no. 11 (2011).

LAQUEUR, Walter, 2010. “Moscow’s Modernization Dilemma”, Foreign Affairs, no. 89, issue 6 (November/December 2010).

MARKIT, 2013. “HSBC Russia Manufacturing PMI” (December 27, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MAU, V., 2013. “Mezhdu modernizaciej i zastoem – ekonomicheskaia politika 2012 goda” (Between Modernization and Stagnation – Economic Policy of 2012”, Voprosy ekonomiki, no. 2 (2013).

MEDETSKY, Anatoly, 2013. “Putin Promises $13.6Bln in Infrastructure Spending”, The Moscow Times (June 21, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MEDVEDEV, Dmitrij, 2009. “Rossiia, vpered!” (Russia, Forward!) (September 10, 2009), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MINAEV, Sergej, 2013. “Patrioticheskij kredit” (Patriotic Credit), Kommersant (June 24, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, 2013. “Prognoz dolgosrochnogo socialno-ekonomicheskogo razvitiia Rossijskoj Federacii na period do 2030 goda” (Prognosis of Long-Term Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation Through 2030), (Moscow: March 2013).

MOUKINE, Guennadi, 2013. “Minister Pushes Intensive Approach to Economic Salvation”, The Moscow Times (October 2, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (A). “Economists Gloomy on GDP Growth Prospects in 2014” (December 27, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (B). “World Bank Cuts Growth Forecast” (September 26, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (C). “IMF Cuts Russia Growth Forecast “ (September 25, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (D). “Russia’s Tax Climate Rated 56th in the World“ (November 21, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (E). “Ministry Stakes on Investment” (September 26, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (F). “Putin Warns Against Draining All Fiscal Reserves” (November 8, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2013 (G). “Siluanov Says Budget Shortfall of $30Bln Could Be Covered by Reserve Fund”, The Moscow Times (July 5, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2014 (A). “Russia’s Economy Retracted in January, Report Says” (February 21, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2014 (B). “Russia Jumps to 44th in Bloomberg Business Rankings” (January 23, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2014 (C). “Siluanov Says Russia’s Ukraine Bailout Mostly Coming from National Welfare Fund”, The Moscow Times (January 27, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2014 (D). “Shuvalov Sees Government Role in Economy Dropping to 25% by 2020” (January 16, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

MOSCOW TIMES, The, 2015. “Russians Must Adapt to More Unemployment – Deputy Prime Minister” (January 23, 2015), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

OPEN ECONOMY, 2014. “Russians Keep Cash in Banks, Not at Home” (September 29, 2014), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

PRIBYLOVSKY, Vladimir, 2013. “Clans are marching”, oDR (May 30, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

RIANOVOSTI, 2007. “Russia among top 5 in terms of GDP by 2020“ (June 9, 2007), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

REUTERS, 2014. “Russian cbank raises key interest rate to 7 percent from 5.5 percent” (March 3, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

REUTERS, 2015. “Putin’s Tunnel Vision on Defense Sharpens Russia’s Economic Crisis”, The Moscow Times (January 16, 2015), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

RYZHKOV, Vladimir, 2014. “Protivorechnaia politika neinvestirovaniia v chelovecheskij capital” (Contradictory Policy of Not Investing Into Human Capital), Rossiia v globalnoj politike (February 19, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

SCHRÖDER, Hans-Henning, 2014. “Politik in Zeiten nationaler Verzückung“ (Politics in Times of National Ecstasy), Russland-analysen NR. 288 (December 19, 2014), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

SOUKUP, Ondřej, 2013. “S předvolebními sliby jsme se trochu unáhlili, přiznal Putin“ (Our Promises Went Too Far, Admitted Putin), IHNED.cz (September 5, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

SOUKUP, Ondřej, 2014. “Miliardáři si stěžují na zásahy Kremlu” (Billionaires Complain About Kremlin´s Meddling), IHNED (October 22, 2014), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

TOKAREVA, Anna, 2013. “Gossektor v ekonomike Rossii” (State Sector in Russian Economy), Kommersant (July 15, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL, 2013. “Corruption Perception Index 2013”, Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

VISLOGUZOV, Vadim, KRIUCHKOVA, 2015. “Fond raciol´nogo blagosostoianiia” (Rational Welfare Fund), Kommersant (January 29, 2015), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

WEAVER, Courtney, 2013. “Russia gives green light to stimulus programme”, Financial Times (July 25, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

WORLD BANK, 2013 (A). “Russian Economic Report 30” (September 25, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

WORLD BANK, 2013 (B). “Doklad ob ekonomike Rossii, No. 32” (Report on Russian Economy, No. 32) (September 2014), Online, accessed February 16, 2015.

WORLD BANK, 2014. “Russian Federation”, Doing Business 2014, Online, accessed November 10, 2014.

ZOTIKOVA, Oksana; DOROFEEV, VLADISLAV, 2013. “Katastroficheski ne khvataet kadrov” (The Lack of Specialists is Catastrophic), Kommersant (May 29, 2013), Online, accessed November 10, 2014.