The republic of Moldova may to some appear to be something of an afterthought – a small, landlocked nation on the far eastern periphery of Europe without any well-known cities or other attractions. However, despite its small size, Moldova is home to a staggering array of different nationalities, religions, and cultures. With a rich history reaching back far into the ancient world, Moldova at least has a proud past, despite its uncertain future.

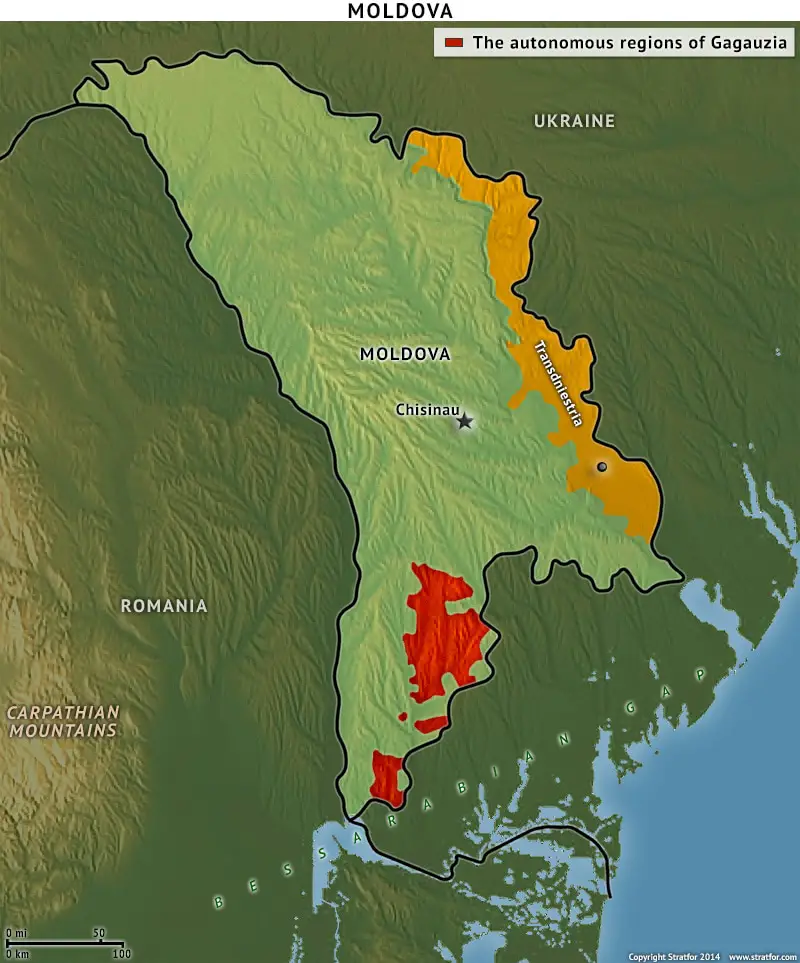

Traditionally on the borders of larger states, Moldova has seen conflict for generations, and, despite a brief interlude of relative stability under communism, Moldova today is once more fractured. Although Gagauzia (the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia) has now been reintegrated with the greater state of Moldova, Transdnestria (the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic) still proclaims itself independent and has a seperate, unrecognized government. The rest of the country is torn almost equally between communist-leaning rural areas and western-leaning urban areas, meaning that most elections are heated and very close.

A map showing Moldova and the disputed area of Transdnestria (in yellow) and the formerly disputed region of Gagauzia (in red), a region that had also once sought independence but which instead negotiated a status of “autonomous region” within the Moldovan state.

A Short History of Moldova

The present territory of Moldova has been occupied by numerous waves of different peoples from the Stone Age on. In antiquity, the region was occupied by Dacian tribes who were later displaced by successive waves of groups such as the Bulgars, Pechenegs, Kipchaks, Tatars, and Mongols. This constant immigration contributed to creating the diverse and fractious ethnic and linguistic environment of present day Moldova.

The first ancestor of the modern Moldovan state appeared in 1359 with the establishment of the Principality of Moldavia, which consisted of the current territory of Moldova as well as portions of modern-day Ukraine and Romania. This was based on a buffer territory created by the king of Hungary to serve as protection against the Golden Horde. The Principality was formed when the prince sent to rule the territory rejected the authority of his king and proceeded to peruse his own political aspirations.

However, despite a brief period of relative prosperity under the strong government of Steven III, The Principality succumbed to its status as a small, divided country surrounded by enemies. It found itself subject to repeated invasions from all sides, and spent much of its existence as a tributary-state to various neighboring powers such as the Golden Horde, the Khanate of Crimea, The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and, of course, the Kingdom of Hungary before finally coming under Ottoman control in 1538.

In 1812, Moldova was ceded by the Ottoman Empire and incorporated into the Russian Empire as the Oblast’ of Moldavia and Bessarabia. Under Russian rule, further immigration added considerable minorities of Ukrainians, Jews, Gagauz, Cossacks, Bulgarians, and Germans, decreasing the actual Romanian-speaking Moldovan population of the territory to only 52%.

In the tumultuous first half of the twentieth century, Moldova saw both widespread destruction and also great development. With the Russian Revolution in 1917, Moldova entered a period of great upheaval, going through several transitional governments and a brief union with Romania before the formation of the Moldavian SSR in 1940.

A monument to Steven III in Chisinau, the capital Moldova.

During the Second World War and the period immediately thereafter, the Moldovan population suffered greatly – during the conflict, the Germans deported or exterminated approximately 300,000 Moldovan Jews, while roughly 250,000 Moldovans were drafted into the Soviet Army. The postwar years brought further chaos, as 1946-7 saw widespread famine in Moldova resulting in an additional 216,000 deaths. Extensive purges by the NKVD of intellectuals, nationalists, and “bourgeois elements” further destabilized society.

In order to repopulate areas devastated during the wars, large numbers of Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians were settled in Moldova, adding a new layer to the ethnic makeup of the territory. The Soviet government also tried to discourage external influences in Moldova by creating a more unique “Moldovan” identity. While previously the Romanian-speaking Moldovans had largely identified with the Romanians across the Carpathians, during the soviet period Moldovan was written in Cyrillic script, rather than the Latin alphabet used by the Romanians, complicating communications across the Carpathians. During the later Soviet period, substantial funds allocated from the Soviet budget helped to build up commerce and encourage urbanization, resulting in the growth industries such as that of Moldovan wine production, which was revered in the USSR and remains one of Moldova’s major exports.

As a result of these actions, toward the close of the 20th century Moldova was wealtheir and more developed than it had ever been. However, despite its new prosperity, Moldova’s significant ethnic and political divisions had only deepened during the twentieth century, and after fifty years of suppression under Soviet bureaucracy they all came to the surface in the newly independent Republic of Moldova.

Modern Moldova: Independent and Divided

Under the thaw of perestroika, Moldova rapidly moved away from Soviet ideology and towards a more national, independent Moldovan state. In 1989, a law was passed reinstating the Latin alphabet as the official written alphabet for Moldovan, and the first democratic parliamentary elections were held in 1990. In 1991, following the unsuccessful Communist coup against Yeltsin, Moldova formally seceded from the USSR.

Independence celebrations were short-lived, however, as Moldova was soon plunged into economic depression and civil war. Alienated by the growing nationalism of the dominant Romanian-speaking Moldovans, minorities in the country grew increasingly uneasy.

The south of Moldova is home to large minorities of Gagauz, an ethnic group which speaks a Turkic language, while in Transdnestria, the small strip of land east of the Dniester river, Russians and Ukrainians made up the majority of the population. In 1991, both of these areas declared independence from the new Republic of Moldova, creating the republics of Gagauzia and Transnistria.

Moldova attempted to recover Transnistria through military force, leading to open warfare in the winter of 1991-2. Transnistria retained its defacto independence, supported by Russia and Ukraine. It became apparent that if Moldova were to avoid further disintegration, it would have to allow for more minority rights, and allow the Gagauz and Transdnestrians greater political and cultural autonomy.

In the mid ’90s efforts were made to reach out to Gagauzia and Transnistria, and while Transnistria remained wholly independent, a tenative accord was reached between Gagauzia and Moldova in 1994. The Moldovan parliament recognized the autonomy of Gagauzia within Moldova and granted it the right to “external self-determination,” in exchange for Gagauzia returning as part of the Moldovan state, though with considerable rights of self-government.

The Current Government of Moldova

While Moldova has not been wholly unsuccessful in building a post-Soviet government, it still has a long ways to go in building a viable democracy and effective state. Moldovan politics in the post-soviet period have been contentious, and at present have left the country with only an acting government.

Despite the initial successes of liberal groups such as the Democratic Agrarian Party and the outlawing of the Party of the Soviet Union in 1991, popular sentiment quickly turned against the new government, largely due to the economic collapse and ethnic conflict which quickly spread throughout the new country.

In the late ’90s, a renewed Communist Party took power, first gaining the presidency and then the parliament in the 2001 election, making Moldova the first post-Soviet nation to reelect a communist government. The communists further amended the constitution to prevent direct election of the president, instead allowing the parliament to select the president. This resurgent communism provided liberal parties with impetus to join together and present a united front, which succeeded in gaining a narrow minority in parliament in the 2009 election.

Unfortunately the margin in parliament was too narrow to allow either party to elect a president, and Moldova remained governed by an acting president and parliament until March 2012, when Nicolae Timofti, a progressive from the Alliance for European Integration, was elected as a consensus candidate. However, this was done with considerable finesse of the parliamentary rules, including a last-minute rescheduling of the vote that resulted in several members of the Communist Party being absent from the vote. Given the controversy surrounding this, how effectively Timofti will be able to use his mandate has yet to be seen and is doubtful.

The Modern Moldovan Economy

At the same time as this political strife, Moldova went through a drastic economic shift as it transitioned to a market economy, which resulted in high inflation and widespread emigration. The situation stabilized somewhat following the adoption of the leu as the new official currency, and in the 2000s, Moldova began to see growth.

Nicolae Timofti, with the Alliance for European Integration, was elected president of Moldova in 2012, ending three years of political stalemate. Photo from Elldor.info

Despite the economic turnaround, Moldova still suffers from brain drain and other emigration – nearly 38% of Moldova’s GDP comes from remittances from Moldovans who have gone abroad to find work to support their families. Most of these Moldovans left hastily and work in their destination countries illegally often for lower-than-average wages in industries such as construction. Russia is said to have the most Moldovan immigrants, with some estimates placing them at 200,000, although Italy is said to have nearly as many.

Furthermore, as a small country, Moldova’s economy produces relatively few exports, which consist mostly of agricultural products and alcoholic beverages such as wine. Given its history, and given the fact that many of its manufactured exports are still made with Soviet technology, meaning that they are considered uncompetitive in much of Europe, most of these exports have historically gone to former Soviet states and predominantly to Russia. Thus, when Russia twice declared an embargos on Moldovan wine, once in 2006 and again in 2010, ostensibly because of health concerns about pesticides used on the grapes, the embargo was considered to be an effective political tool that had been used during low points of Moldovan-Russian relations.

Moldova also finds itself largely dependent on other countries for energy, importing hydrocarbons from Russia and Ukraine, and producing only 30% of its needs itself. This has also caused tensions between Moldova its two Slavic neighbors.

While Moldova is making progress at reforming its economy, it will likely not get the investment it needs to truly fix its economic and infrastructure problems until it can show that its political situation has stabilized. Despite this, the services sector in Moldova is growing and include IT services that remain competitive given Moldova’s low wages and services such tax processing and payroll services for companies operating in larger countries such as Russia. For the later services, Moldova takes advantage of not only its own low wages, but also the still-strong Russian skills of its citizens.

However, most of Molodva’s few tourists will likely be most struck by the preponderance of poor-quality roads and rail services and the distinctly “Soviet” feel, with grey, boxy concrete building, that pervades most of Moldova, including its capital, Chisinau. It is one Europe’s poorest countries.

Moldova in International Relations

Moldova has been trying to become a more integrated member of greater Europe since achieving its independence, and seeks to cultivate international ties with the West. However, it is hindered in this endeavor by its political difficulties and the frozen conflict in Transdnestria.

Traditionally, Romania has been Moldova’s closest ally, and was the first state to recognize the independence of Moldova. The countries are historically linked and many Moldovans speak Romanian as a native language.

Ukraine has increasingly become a close trading partner, yet Moldovan-Ukrainian relations are still hindered by controversy over the fate of Transdnestria and how to treat the Transdnestrian border. While Ukraine has never formally recognized Transdnestria (no country has), it has periodically allowed trade with Transdnestria across their shared border, a point of contention with Moldova. Moldova gets approximately 70% of its energy from Ukrainian pipelines transporting mostly Russian gas and oil, and during periods of economic duress has racked up large debts to its eastern neighbor, a relationship which, as a matter of course, affects any negotiations between the two countries.

Further east is Russia, which has been the strongest supporter of Transdnestrian separatism, and as a result has had a largely antagonistic relationship with Moldova since it gained its independence. Despite a brief warming of relations after Moldova’s communists returned to power, this detente ended in 2003 with the Moldovan rejection of the Kozak Memorandum, a Russian-sponsored resolution to the Transdnestrian conflict. This helped spark a long-lasting chill in Russian-Moldovan relations.

In part to counterbalance increasingly poor relations with its eastern neighbors, Moldova has cultivated its relations with the EU. A member of ENP (European Neighborhood Policy) since 2005, Moldova continues to seek closer cooperation with the EU and eventual membership, though in this is not like to come to fruition while the frozen conflict with Transdnestria and its difficulties in articulating a functioning democracy continue to plague the country. Moldova is a member of the OSCE, the WTO, and the Council of Europe, and would like closer engagement with the NATO alliance and the US, though at present it is overshadowed in Eastern Europe by other states such as Poland and the Baltic nations, which have been quicker to assimilate into Western Europe.

Moldova at present seems to be at a critical point in its development, as a rapid solution must be found to its crisis of government and territory. If the new liberal coalition can create a viable government and institute economic and political reforms, Moldova can likely count on further assistance from the West and cooperation with the EU. However, the prolonged absence of a strong government will continue to destabilize the country, leaving it open to economic dependency on its Eastern neighbors.