Just as the leadership, citizens, and politics of the USSR changed drastically between 1917 and 1991, so too the Soviet kitchen underwent innumerable changes from generation to generation. Every Soviet leader had a unique vision for the USSR, and each leader proposed a different version of what the Soviet kitchen should look like. While in the beginning, the kitchen held little importance in Soviet life, eventually it became a crucial living space that brought out the intricacies of communal life. Later, the Cold War changed the kitchen again by making it the center of a competition with the West, but throughout the last 30 years of the USSR, the kitchen struggled to maintain its place in the socialist agenda amidst a quickly-changing political culture. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the government no longer belonged in the kitchen. Russian kitchen culture lost much of the political spark it had held for the previous 74 years as capitalism rippled through and eradicated the tight grasp the government had held within the Soviet home.

I. Lenin

- Revolts

“Kitchen politics” started with the Bolshevik Revolution, when bread riots helped spark the overthrow of Czar Nicholas II in 1917. Just four years later, a severe cut in food rations caused major strikes in Petrograd right before the formation of the Soviet Union (Von Bremzen 2013, 3). These events were just the beginning of a long trend of the power of food uniting people socially, politically, and emotionally.

- Food as Fuel

When Vladimir Lenin came to power, collective nutrition became the new ideal. Lenin’s administration believed that people were not capable of receiving proper nutrition when they cooked for themselves. Food was simply fuel, and the best way for Soviet citizens to fuel themselves was not within their own homes, but through stolovayas, or government-run cafeterias. Lenin and his administration declared in the 1923 pamphlet Down with the Private Kitchen that stolovayas were not only the best way for the government to control scarce food resources, but an obvious way for communism to permeate the lives of Soviet citizens; eating became a political process dubbed a “food dictatorship” by food writer Anya von Bremzen (Von Bremzen 2013, 40-41).

Stolovayas ensured that Soviets were “liberated from fussy dining” and provided a meeting ground for the creation of a new Soviet society. The goal was to create the ultimate Soviet citizen who was ready to sacrifice even biological needs for the socialist cause (Von Bremzen 2013, 38). The ideal apartments of the Lenin age were built without the bourgeois kitchen altogether – in fact, apartments were appropriated as communal “dwelling spaces” rather than homes, and the official allowance of apartment space per person was set at only nine square meters. One of the goals of this kitchen movement was to liberate women from the unnecessary chore of cooking and enable them to develop interests in more cultural pastimes such as the arts in order to inspire an idea of romanticism that spanned the revolutionary years of the Soviet Union(NPR 2014).

- New Economic Policy

In 1921, the newly-socialized kitchen took a slight turn. After a poor grain harvest and subsequent food rationing, Lenin understood that rioting Soviet citizens had to be fed and enacted a program called the New Economic Policy to grow the economy and feed hungry mouths as quickly as possible. This program helped food politics inch away from the realm of socialism by eliminating forced grain requisition in the counryside and introduced small-scale private businesses such as food carts, pop-up shops in people’s homes, and workplace canteens to help feed the masses. This policy was greatly successful in putting food on the table throughout the rest of Lenin’s administration, bringing his reign over Soviets’ kitchens and stomachs to an optimistic close (Von Bremzen 2013, 41-42).

II. Stalin

- Communal Living

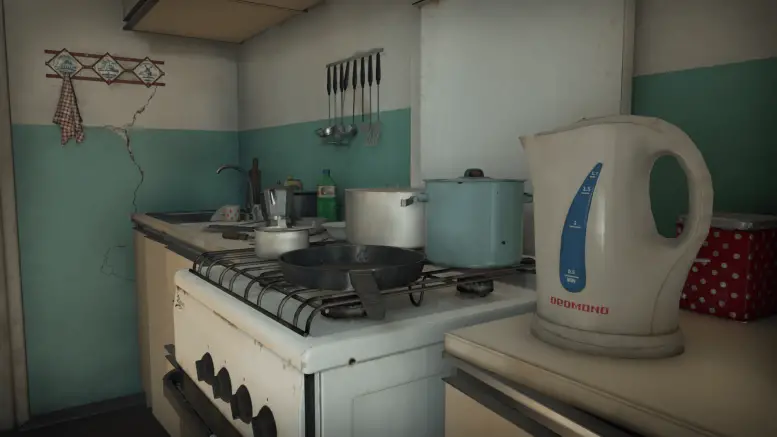

Under Joseph Stalin, the NEP of Lenin’s time was not sufficient to creating the agriculture growth that Stalin felt the country needed. Further, a new grain crisis left the country hungry once more. Kitchens made a comeback because of heavy food rationing and made communal living more hectic than ever. Communal apartments meant that several families were all sharing a small kitchen; while one might imagine that communal kitchens provided a space for camaraderie as families happily cooked together, this could not have been farther from the truth. In reality, these communal living spaces functioned as the perfect arena for neighbors to eavesdrop on each other’s conversations, accuse each other of stealing cooking utensils, and even report suspicious activity to the government. Citizens in communal apartments generally used the kitchen as swiftly as possible and retreated to their own rooms to eat (NPR 2014).

- Mikoyan’s First Journey

In 1936, People’s Commissar of the Soviet food industry Anastas Mikoyan traveled to the United States to research the American food industry. During this time, it was nearly impossible to find anything but the most basic consumer goods in the USSR. While Mikoyan was in America, Soviet factories were just beginning to produce consumer goods instead of heavy industry for the first time, and the Soviet consumer was born. Mikoyan returned with many ideas about what the Soviets could adopt from America that would make life easier, such as prepackaged foods and flash freezing (Von Bremzen 2013, 76-77).

Many of the foods that Russians claim to be Soviet classics from their childhoods are, in reality, ideas that Mikoyan brought back from the United States and put a Soviet spin on. Russians consider kotleti (meat patties) and sosiski (sausages) to be staple foods from generation to generation, but these foods actually began as American hamburgers and hot dogs from Mikoyan’s many factory tours. He was fascinated by American ice cream and was tasked with buying ice cream machines to bring back to the USSR, where factories began opening with gusto. Refrigerators, freezers, and manufactured ice were developed in conjunction with the new ice cream craze that quickly overtook the nation (Gronow 2003, 116-118). With a range of new products, Mikoyan was able to use his new knowledge of packaging, merchandise displays, and food processing factories to greatly change the course of Soviet dining.

- Development of Restaurants

Before 1936, the USSR had few genuine restaurants, instead focusing on providing Soviet people with the proper nutrition through stolovayas, and then through workplace and school canteens. After some time, the Soviet government realized that the standard of living could be greatly improved if citizens could visit with friends and family while eating, rather than simply eating for nourishment at work. Mikoyan declared, “We have to provide our workers and employees with such a possibility of rest, or cultured use of time” (Gronow 2003, 107).

In 1935, new measures were developed to set restaurant standards in order to control the spread of restaurant culture. The Central Administration of Restaurants and Cafes was founded in January of 1936, and it immediately set out to improve the quality of food by allowing restaurants to set higher prices than canteens and broadening consumer choices (Gronow 2003, 108). It also categorized restaurants into three groups based on quality and price, which included restaurants in workplaces and schools that were closed to the public; canteens, cafes, tea rooms, and bars that were open to the public; and traditional restaurants with fine table settings and higher-quality food. These new restaurants greatly raised the Soviet standard of living and even helped cultivate table manners (Gronow 2003, 109-110).

In 1937, the government decided that the Central Administration of Restaurants and Cafes had disrupted the status quo set by the Communist Party, and the directors of the organization were arrested for “leading the institutes of social nourishment into a wrong and harmful direction with disastrous consequences” (Gronow 2003, 111). With the new abundance of dining options, Soviet food preference had changed too drastically for some officials, who believed that the newfound popularity of meat over vegetarian dishes was harmful to Soviet life and showed “a criminal tendency” on the part of the organization, when in reality it was indicative of a higher standard of living (Gronow 2003, 112).

The restaurants and canteens that were left after the government closed many of them soon experienced a severe food shortage. Many blamed the shortage on the prevalence of restaurants, using them as a scapegoat for an obviously agricultural problem. The development of Soviet restaurants was deeply politicized, splitting people between those who saw food only as nourishment and those who believed that food could lead to an elevated society. Eventually, no one in the government could resist the economic benefits of restaurant culture, and a new boom of development began at the end of the 1930s (Gronow 2003, 114-115).

- The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food

In 1939, the Ministry of Industry and Production of Consumer Goods of the USSR, led by Anastas Mikoyan, published The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, a kitchen bible of sorts that has had twelve different editions and is still sold to this day, in multiple languages. The 400-page book was the government’s direct route into the Soviet kitchen, and with one in nearly every kitchen across the fifteen republics, it was easy for Mikoyan to control what and how people ate. Mikoyan’s book does not disguise how intertwined the government is with kitchen life: quotes from Lenin and Stalin are prominent in various editions at the beginning of the book, praising a socialist way of eating (Mikoyan 1954).

The book’s lengthy introduction features an optimistic outlook on the great improvement of Soviet kitchen life through the years. In the 1954 version, Mikoyan wrote: “The Government and Central Committee of our party recognizes that the production of consumer goods achieved in 1953 was insufficient, and that it is necessary to greatly increase the volume of production of goods of mass consumption, expand all types of industry, take measures to diversify Soviet goods, and also raise the general standard of living” (Mikoyan 1954, 13). He goes on to list Soviet accomplishments, making a convincing argument to the reader that the Soviet government’s food policy is in the interest of the people and is far superior to that of capitalist societies, which are seemingly falling behind (Mikoyan 1954).

Before directly addressing recipes, Mikoyan wrote several chapters about proper procedure and etiquette in the Soviet kitchen; these are not merely suggestions, but stringent rules that became ingrained in the Soviet lifestyle. These chapters include an explanation of proper nutrition habits, a description of which ingredients and dishes are appropriate for the different meals of the day, a summary of the correct order in which to cook and serve a meal, and information on kitchen sanitation techniques and correct food storage. The recipes themselves are also highly politicized: despite the fact that recipes appear and disappear through the multiple editions, there is always an overarching theme of seeming abundance and prosperity. Soviet citizens knew that the book was riddled with recipes that they could never find the ingredients for, but nevertheless, they faithfully bought volume after volume and scrounged and substituted to abide by its instructions as best they could (Mikoyan 1954, 18-32).

III. Khrushchev

- Consumer Culture Develops

During the 1950s, Nikita Khrushchev’s goal was to return to the concept of single-family flats – even if they were cheaply built with no frills, they gave Soviets privacy and peace of mind. There were many in the government who disagreed with this idea, claiming that when families lived alone, socialism was replaced with bourgeois consumerism (Reid 2002, 242-243). Magazines of the time wrote to women and teenage girls, reminding them that even in a time of demand for consumer goods, they should still be cautious and live a modest lifestyle. Women were targeted more than men when it came to information on consumption (Reid 2002, 248-250).

In 1957, the Advertising Workers of Socialist Countries held a conference in Prague to define the purpose of advertising in countries where consumerism was frowned upon. The conference devoted attention to shaping consumer taste to favor a higher standard of living while remaining rational, unlike in the West where advertising strived to convince consumers to buy things they did not need. Although the USSR and its advertising workers were committed to advocating for more mass consumption, it was still very much a culture of shortages (Reid 2002, 218).

In 1955, Mikoyan once again visited the United States, this time on a mission to study domestic appliances to help make women’s lives easier. The Soviet Union was making incredible technological progress in space, but much of this technology was lacking in the kitchen. Mikoyan said to the American press, “We have to free our housewives like you Americans! The Russian housewife needs help” (Reid 2002, 227). Khrushchev promised women more appliances during public addresses both in 1958 and 1959 (Reid 2002, 228).

- Cold War Ideas

The Soviet push for higher living standards soon grabbed the attention of the West, but with a drastically different consumer culture, it was difficult for those in capitalist countries to comprehend that Soviet consumerism was a separate breed. “Operation Abundance,” as sociologist David Riesman put it, was considered an alternative to the arms race during the Cold War. Riesman claimed:

If allowed to sample the riches of America, the Russian people would not long tolerate masters who gave them tanks and spies instead of vacuum cleaners and beauty parlors. The Russian rulers would thereupon be forced to turn out consumers’ goods, or face mass discontent on an increasing scale. By bombarding the USSR with Toni wave kits, nylon hose, stoves, and refrigerators, the United States would force Moscow to abandon weaponry for consumer goods. (Reid 2002, 222)

Riesman believed that Soviet women’s desire for consumer goods would become so great that the USSR would cave under the pressure of consumerism and quickly turn to capitalism. Many in the West assumed that Soviet women had the same consumerist desires as women in capitalist countries, and American journalists popularized the myth that Russian women were spiraling out of control to achieve the things that Western women had. While “Operation Abundance” did not come to fruition, Khrushchev felt that more changes had to be made in order for the Soviet Union to advance.

In response to America’s challenge in mass consumption, Khrushchev announced a seven-year economic plan in 1959. As the American government had already done, he accepted mass consumption as a sign of economic growth and promoted reforms aimed at winning the competition against the US to raise living standards. Khrushchev accelerated the development of machinery to increase both agricultural production and consumer goods with the hopes of overtaking the United States in all outputs. He firmly believed that outproducing the US in butter was more valuable for socialism than outproducing the US in war missiles. Some of Khrushchev’s lofty goals included producing 76% more silk, 110% more meat, 60% more fish, and 100% more chore-lightening machines and appliances (Hamilton & Phillips 2014, 89-91).

IV. Brezhnev, Gorbachev, and Beyond

- A Safe Space

After Khrushchev’s push for single-family homes, the 60s and 70s, under Leonid Brezhnev, were a booming time for socialization in the kitchen. Kitchen circles were “groups of friends who met in the kitchens of their apartments and led endless conversations about the meaning of creation, art, and politics” (Greenfeld 1992, 23). It was impossible during this time to have political discussion in public, so Soviets took to their kitchens to discuss taboo art, music, and literature, and to vent against “the system.” In these circles, citizens could imagine a life before the Soviet Union based on Russian nationalism and cultural superiority (Greenfeld 1992, 23).

Since the revolution, intellectuals were considered by many to be superior citizens, prized for their contributions to Russian culture, but Brezhnev’s administration dubbed the types of intellectuals who participated in kitchen circles enemies of the state because many were opposed to the Communist Party. Intellectuals continued to feel morally superior to their peers, but they experienced hostility in the outside world and sought out spaces where their contributions were appreciated. Kitchen circles provided intellectuals with social fulfillment during a time in which mass society disrespected them (Greenfeld 1992, 22).

- The Breakup

When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, he attempted to work with the intelligentsia rather than fighting against them by offering them glasnost and foreign travel. Many in the kitchen circles saw this as a ploy to trick them into bringing their circles into the open where they would then be arrested. It took until 1988 for the intelligentsia to understand that coming out of their shells was for the best, and they began to take advantage of the opportunity to openly bring down the system. The kitchen circles were a large reason that Gorbachev took the steps that he did for perestroika and glasnost, because they were able to comment on the widening gap between communism and capitalism (Greenfeld 1992, 23).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, kitchen circles quickly began to disintegrate due to the advances of capitalism. The basis of the camaraderie of the kitchen circles had always been the value of friendship over economic happiness, but with the rise of capitalism, many shifted their focuses. And now, without a clear enemy, the intelligentsia realized that their common bond was eradicated (Greenfeld 1992, 24). With the kitchen circles dismantled, the Soviet kitchen, and generations of an evolving kitchen culture, became history. The new Russian kitchen that began with the arrival of capitalism is an ever-evolving mix of the old world traditions that have been instilled since the days of Lenin and the new free market culture of exotic ingredients and fast food burgers.

V. Conclusion

From Lenin to Gorbachev, every Soviet leader had an immense impact on what was happening inside people’s kitchens. The Communist Party was carefully intertwined with Soviet citizens’ personal lives, and this was clearly visible within kitchen culture. When the Soviet Union collapsed and the government no longer held the same overt importance in everyday life, the kitchen stopped serving as a meeting ground between the Party and the people. The nostalgia that many Russians experience today can be tied to the thriving food politics of the USSR – a time when kitchen culture – whether unifying friends through kitchen circles or breeding conflict in communal apartments – was imbued not just with the smell of food, but with political and social meaning.

Works Cited

Greenfeld, Liah. “Kitchen Debate.” New Republic 207.13 (1992): 22-25. Military and Government Collection. Web. 30 Sept. 2014.

Gronow, Jukka. Caviar with Champagne: Common Luxury and the Ideals of the Good Life in Stalin’s Russia. Oxford: Berg, 2003. Print.

Hamilton, Shane, and Sarah T. Phillips. The Kitchen Debate and Cold War Consumer Politics: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford St Martin’s, 2014. Print.

The Kitchen Sisters. “How Russia’s Shared Kitchens Helped Shape Soviet Politics.” The Salt. 20 May 2014. National Public Radio. Web. 30 Sept. 2014.

Mikoyan, Anastas, and Ministerstvo Promishlinosti Prodovolstvenih Tovarov USSR. Kniga o Vkusnoy i Zdorovoy Pische. Moscow: Pischepromizdat, 1954. Print.

Reid, Susan E. “Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev.” Slavic Review 61.2 (2002): 211-52. JSTOR. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

Von Bremzen, Anya. Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking: A Memoir of Love and Longing. New York: Crown, 2013. Print.