“I would like you to know that Serbia is Russia’s partner in the Balkans…Serbia loves you. And you deserved this love by the manner you rule Russia.”

-President Nikolić to President Putin (Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, 2013, p. 4)

In a world where everyone is out for him or herself, there are still individuals who believe that brotherhood and fraternity can transcend self-interest. Serbia’s President Tomislav Nikolić may be one of those people, if you ask him how he feels about Russia, a country that shares Serbia’s Slavic and Orthodox background. Yet for other Serbs, that is all they have in common with Russia, and some view the giant to the north with suspicion. My task in this paper is not to defend either view, but to understand how one comes to such conclusions about Russia, what Russia means for Serbs today in terms of historical memory, and how relations with Russia might help or hinder Serbia.

In order to study these questions, I conducted primary research with Serbia’s political youth. I also interviewed two experts on the state of affairs between Serbia and Russia. My hypothesis was that I would hear a variety of opinions about Serbian-Russian relations, but that these would likely match those presented by the individuals’ respective parties, and that many people would know little about the history of those relations. In some ways, the interviewees surprised me. Their knowledge of history was more extensive than expected, but it lacked depth, and interpretations of history varied wildly. For many, even those with some sympathy towards Russia, it was clear that Russian interests did not always coincide with those of Serbia, though there was no consensus or pinpointing of Russia’s exact interests in Serbia. Finally, there was little grey area when discussing how relations with Russia might harm or benefit Serbia. Most participants had a strong opinion in one direction or another. The least extreme answers I received were those that proposed the strengthening of cultural ties but nothing else. The conclusion of this paper will discuss all of these findings in greater detail, as well as introduce some expert opinions on how Serbs came to these conclusions about Russia.

Methodology

This research project is primarily based on semi-structured interviews with political youth, both in person and over e-mail, and largely in Belgrade.[1] However, some participants interviewed via e-mail hailed from different cities in Serbia. All names have been changed to preserve anonymity. Appendix 2 contains brief descriptions of the political parties in Serbia to which my participants belonged. I conducted a total of thirteen interviews, including two with experts on Serbian-Russian relations. Most of my interviews were arranged either through my own contacts or those of my Serbian advisor Igor Novaković,[2] although a few developed from my original contacts through my Belgrade study abroad program offered through the University of Colorado Boulder.[3] In the fall semester of 2013, I was engaged in the School of International Training (SIT) Peace and Conflict Studies in the Balkans program, based out of Belgrade. The interviews asked for basic information about education, place of origin, position in a political party, and then proceeded to specific questions about the history of relations with Russia and perceptions about these relationships, and both positive and negative aspects of relations with Russia. I developed these questions, listed in Appendix 1, after completing my background research, and they were revised and augmented by my Serbian advisor.

There were several reasons why I decided to do my research on the complex relationship between Serbia and Russia. Serbia is becoming increasingly involved with Russia in sectors such as energy, economics, and military, and sometimes this involvement is perceived to have adverse consequences for Serbia’s prospective EU membership. Since the EU and Russia are considered two of Serbia’s “four pillars of foreign policy,”[4] additional research on these complexities is warranted. My target population was political youth, ages 18 to 28.[5]

There are many areas of my life which affect my positionality in this project. My position as a young American student makes me possibly biased in favor of the West, although my university Russian major may make me more prone to overestimate the influence of Russia and its importance within Serbia. As an outsider and a young person, I did not experience the breakup of Yugoslavia, and I do not have practical experience of it or its aftermath. Because I am an American, people who are fond of Russia may be less willing to talk to me because of the belief that the US and Russia still have a rocky relationship. For this reason I was very careful not to appear biased in any of my questions. The limitation of needing to conduct English-language interviews prevented me from talking with people who were less influenced by the West and who might be possibly more sympathetic towards Russia. Completing my research in Serbia but writing my thesis in the US did not allow me to supplement any further questions I had with additional research. As for my advantages, being of a similar age as my participants may have helped in producing a more natural and comfortable interview atmosphere. Having studied the region’s history and the background of my topic, I presented myself as an informed interviewer whom my participants respected.

Historical Relations between Serbia and Russia

- The Middle Ages to 2008

Relations between Serbia and Russia date back to the Middle Ages. Contacts between Serbs and Russians were first formalized (after the sixth century migration of Serbs to the Balkans) in the 15th century (Petrović, 2010). During this time, relations were based solely on the exchange of religious materials between the churches of Serbia and Russia, since at the time Moscow was the only independent Slavic Orthodox country. This non-political relationship lasted until about the 18th century, or until the Russian Empire began to use the Balkans as leverage in its frequent wars against the Ottoman Empire.[6]

In 1724 and 1747 there were great migrations to Russia by Serbs, and a 1774 treaty officially established Russia as the patron of Balkan Orthodoxy. The perception of the Russian tsar at this time was one of a “great Orthodox emperor,” and of Russia as a “third homeland” for Serbian travelers. During the First Serbian Uprising of 1804 to 1813, Serbia unsuccessfully petitioned Russia for aid against the Turks (Cox, 2002, p. 40). But shortly thereafter Russia became engaged in the Napoleonic wars, which pitted it against the Turks and secured Russian support for Serbia. This aid was quickly withdrawn when Tsar Alexander I made peace with the Ottoman Empire in 1807. Russia again came to Serbia’s aid when Russia renewed its conflict with Turkey in 1809, but only until Russia was forced to withdraw aid to protect its own homeland against the Napoleonic invasion. Finally, the 1812 Treaty of Bucharest between Russia and the Turks granted Serbia amnesty and autonomy. Over the history of relations between the two countries, Russia’s aid to Serbia has been mostly conditional, and often sent only when Russia itself was preparing for war with the Ottoman Empire.[7]

After another war with the Ottoman Empire, Serbia expected to be represented and protected by Russia in the peace treaty of San Stefano in 1878. This may have been a reasonable expectation, since Russia intervened in Serbia’s war with the Ottoman Empire in 1876 to prevent its likely defeat (Pavlowitch, 2002, p. 64). However, Russia believed that promoting a greater and independent Bulgarian state was more in line with its interests in the Balkans (MacKenzie, 1967, p. 299). Russia proved willing to sacrifice Serbia to Austrian influence in exchange for Bulgaria. Although other great powers prevented a Greater Bulgaria from developing at the Congress of Berlin, feelings of skepticism towards Russia began to develop in Serbia (Judah, 2000, p. 59). This is important, as it was the first time a real divide appeared as people became more pro-Russian and anti-Russian.

The 20th century saw many vacillations in Serbian relations with Russia. In 1903 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, of which Serbia was a part, was returned to the control of the Karađordević dynasty, which historically maintained friendly ties with Russia (Petrović, 2010, p. 16). This was another important turning point and surely influenced Russia’s support of Serbia in the First World War, which many Serbs see as a great sacrifice on the part of Russia. Of course, the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 changed the game completely, and relations were indifferent and almost absent until the end of World War Two in 1944 and the liberation of Serbia in part by the Red Army. As Yugoslavia transformed into a socialist republic, its leader, Josip Broz Tito, and the USSR’s Josef Stalin were on cordial terms. In 1948, Tito decided that a different strategy for Yugoslavia would be more beneficial. Through the later Non-Alignment Movement, he participated in the creation of the European and global “buffer zone” between the West (US) and the East (USSR). This worked very well for Yugoslavia, and its residents began to identify with this in-between and outsider status (Žiković, 2011, p. 68). People in Serbia were unsure whether Russia represented the true form of socialism or a communist form of despotism (Petrović, 2010, p. 13).

The socialist systems of Yugoslavia and the USSR both began to break down at the same time. While the USSR disintegrated relatively peacefully, Yugoslavia entered into a series of wars which raged throughout most of the 1990s. During the first of these, in Croatia and Bosnia, the weakened Russian state did not make much of an impact. Yet by the late 1990s, as war was taking shape in Kosovo, Serbian president Slobodan Milošević expected Russian leverage against NATO and military assistance (Hosmer, 2001, p. xiii). In addition, only two weeks before war began in Kosovo in 1998, an overwhelming 78% of Serbs believed that Russia would come to Serbia’s aid if Serbia were to be bombed (Judah, 2000, p. 119). However, while Russian public opinion favored Serbia, Russia made it clear to Serbia before the war that it was not interested in a conflict with NATO and that the best option for Serbia would be to accept Kosovo’s fate and avoid war altogether (Vuksic, p. 4). Russia did not assist Serbia in the war.

In 1999, Russia vetoed military action against Serbia in the UN Security Council, but did not take action when NATO disregarded the decision of the Security Council and proceeded to act unilaterally against Serbia. Although Yeltsin supported Milošević as a leader in the Balkans, he did not wish to become involved in a conflict with NATO over Kosovo (Hosmer, 2001, p. 43). In fact, Russia also cooperated with NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR) in 1999 (Vuksic, p. 4); it then withdrew its troops from Kosovo in 2003.

In 2008, Kosovo declared its independence. Despite immediate recognition from Western powers, Russia has refused to recognize Kosovo, citing Russia’s support for Serbia’s territorial integrity. Since Kosovo is a key issue in Serbian politics, Russian support for Serbia created renewed positive perceptions of the Russian state for many people.[8]

- Political Relations 2008 to the Present

Since 2008, Belgrade has included Moscow as one of its concerns in foreign policy. Serbia, in turn, may reap many benefits from its relationship with Russia (Petrović, 2010, p. 7). Trade, investment, and Russia’s support for Serbia regarding Kosovo largely benefit Serbia more than they do Russia (Petrović, 2010, p.7). Russia has also supported Banja Luka in Bosnia and Serbs accused of war crimes. Banja Luka is an autonomous province of Bosnia and Herzegovina which was created by and is comprised of mostly Bosnian Serbs. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has advocated for an early termination of Ratko Mladić’s trial in the Hague on the grounds that the trial violates international law and is damaging to Mladić’s poor health. The benefits for Russia come in the form of “hard security,” or a counter-measure against NATO expansion[9] (Petrović, 2010, p. 7). In what may be seen as another attempt to gain influence in Serbia over the West, in 2009 Russia and Serbia agreed to a “strategic partnership,” coordinating their positions in the fields of politics, energy, and economics (Petrović, 2010, p. 7).

How much influence Moscow has on Serbian politics is a matter of contention, but it is clear that both negative and positive opinions of Russia today are fraught with emotion. For some in Serbia, Russia represents more than a “strategic partner.” Its role is one of protector, and it is a relationship “formed by the historical closeness of the two peoples (defined by ethnicity, not by citizenship), and the common religious and cultural heritage, which were … easy to be transferred to the political level” (Petrović, 2010, p. 5). This is how the relationship between Serbia and Russia is represented to the rest of the world, and Serbian president Nikolić embodies this completely in the following statement: “One should strive to get to know Russia in order to love her even more” (Petrović, 2010, p. 12).

Meanwhile, others in Serbia have a negative impression of Russia, one that often reflects Western biases. Russia is perceived as a consistent prospective colonizer of Serbia, and to some Serbia is consciously letting itself be colonized. This point of view is articulated perfectly by the president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Čedomir Jovanović, who conceded that Serbia “knelt before Russia for Kosovo” when it sold 51% of NIS (Serbia’s gas company), viewed as one of the country’s most valuable assets, to Gazprom Neft, which is majority controlled by the Russian government. No matter how people resolve to interpret Russia’s presence in Serbian politics, the main point of issue is that they are likely to do so without trying to understand Russia’s true positions, intentions, and interests (Petrović, 2010, p. 5). The informed positions of some of my interviewees were therefore surprising.

- Cultural Ties

A common perception of Russia by Serbs is that Russia shares an important Slavic and orthodox history with Serbia. One of their most basic commonalities is the use of the Cyrillic alphabet (although Serbs just as often use the Latin alphabet). Another commonality is Orthodoxy, a Slavic marker that Serbs were able to retain during their occupation by various empires in their history. Relations between the orthodox churches of Russia and Serbia have remained strong since their inception in the 15th century. In October 2013, the Russian Patriarch Kirill gave encouragement to Kosovar Serbs and congratulated Serb leaders on their moral example and refusal to accommodate “immoral ways of life in Belgrade.” The Patriarch was likely referring to Belgrade’s refusal to allow a Gay Pride Parade.

- Energy and Economics

Energy and economics, arguably the two main forces propelling the modern world, have an increasingly important role in the relationship between Serbia and Russia. The biggest project is the construction of the South Stream pipeline in Serbia, which began in November 2013. Approximately one-third of the pipeline runs through Serbian territory and will supply Europe with gas from the state-run Russian Gazprom (Petrović, 2010, p. 133). This is an attempt by Russia to ensure that Europe maintains its consumption of Russian gas, which accounts for one-quarter of all gas imports (Petrović, 2010, p. 133). Europe would like to diversify its gas imports away from Russia, but the construction of this pipeline will be a major deterrent (Petrović, 2010, p. 133).

Russia chose to construct the pipeline partially through Serbia for a variety of reasons, among them Serbia’s sale of 51% of NIS. Russia’s strategy was to find a path to Europe that would bypass Ukraine, a country with which Russia has had turbulent relations (Petrović, 2010, p. 146). Serbia, meanwhile, has traditionally been friendly and is likely to comply with Russia because of the monetary incentives. Such energy sector cooperation has resulted in an additional free trade zone for oil and gas between the two countries (Petrović, 2010, p. 146).

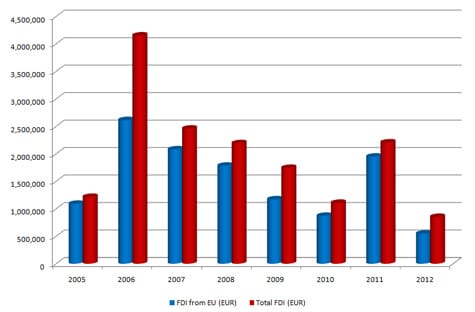

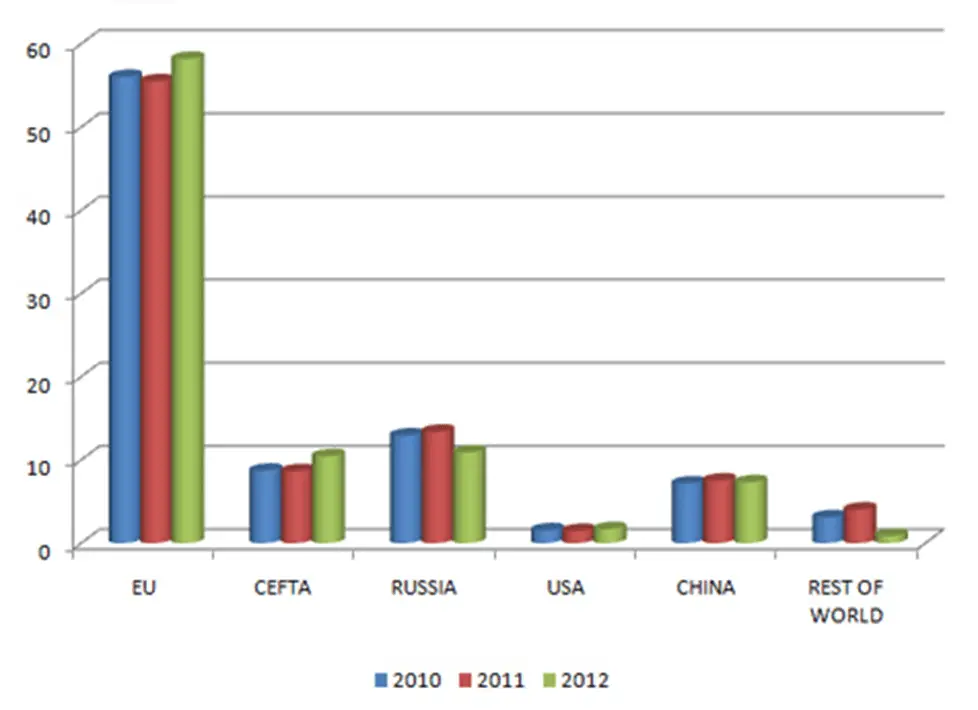

However, other economic ties are more bounded. As of 2005, all major foreign companies invested in Serbia hailed from the EU or the US, except for Russia’s Lukoil (Heuberger & Vyslonzil, 2006, p. 103). A 2012 study from The Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Serbia shows that, from 2005 to 2012, 62% to 89% of all Serbia’s foreign direct investment each year came from the EU. Around 60% of Serbia’s exports and imports are tied to the European Union. Serbia also has extensive trade with CEFTA (Central European Free Trade Agreement), a group made up of Central European non-EU states.[10] Trade with Russia accounts for about 11% of Serbia’s total imports and 8% of total exports.[11]

- Serbia between East and West

Serbia maintains a unique and troubled position between the East and West in Europe. Serbs would like to retain a similar position to the former non-aligned Yugoslavia, and yet they are also attempting to build their own post-war, post-socialist, post-Yugoslav identity. The current world order does not make this easy. In a poll featured in “Nation as a Problem or a Solution” (2008, p. 48), Serbs stated that, on a scale of 1 to 100, their closeness to Europe was 54 and in a poll taken by the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy in 2012, the results were still split (p. 13). Half of the respondents felt that Serbia should join the EU, but there was also an increase in Euro-skepticism compared to previous years. When given the choice of what is best for Serbia’s security, more Serbs responded with neutrality (44%) than any other response. The two groups that advocated closer ties with Russia or the EU were similar in size (18% and 16% of respondents respectively). One of my reasons for interviewing members of political parties comes from a conclusion of the 2012 study, which was that political parties had a significant influence on the participants’ views of Russia. Although there was no overwhelming “winner” between the West and the East in the poll, it is interesting to note that the countries which Serbs regarded as “friendly” (Russia, Greece, and China) are also “Eastern”[12] and Serbia’s “enemies” (USA, Germany, Albania[13]) fall into the “Western” category.

Countries around Serbia have successfully sought to be classified as either East or West (Žiković, 2011, p. 89). Serbia has not been so successful in this strategy, resulting in two main problems. One is its declared “neutrality,” and the other is how this “neutrality” affects Serbia in regard to the EU, NATO, and Russia. When speaking with my interviewees, many of them mentioned Serbia’s neutrality, but an expert, Ivan Stankić, told me that Serbia is certainly not neutral. Yet what does it mean to be neutral, and how can we conclude that Serbia is in fact not neutral? Serbia’s inability to declare a stance, even a neutral stance, can be found in its key security documents (Novaković, 2012, p. 11). The documents lack a statement of the official neutral status of Serbia, and Serbia allows the presence of foreign troops and bases on its territory, indicating that it is not officially practicing neutrality.

Serbia’s second problem is that “Serbia cannot take a neutral position if the EU and Russia differ” (Petrović, 2010, p. 37). This statement can be attributed to how Serbia is swayed by Russia, but has made entry into the EU its top priority. Because Russia would benefit from having a friend in the EU, it does not criticize Serbia’s plans as it has other former Soviet states with EU aspirations (Timofeev 2010). However, where NATO is concerned, Russia takes a different, more complicated stance.[14] After the Serbian Minister of Defense suggested joining NATO, Russia threatened to retract support over Kosovo (Petrović 2010, p. 99). NATO, as a military alliance, can be seen as a direct threat to Russian security, unlike the EU, because “Russia defines security in geopolitical terms” (Petrović 2010, p. 104).

Two Expert Opinions

It’s the old story that we keep playing on: should we join the kingdom of heaven or should we join the kingdom of earth? That’s just silly, that’s not a choice. The state can’t join the kingdom of heaven. That’s a personal thing.

– Dragomir Kojić (Interview in Belgrade, 19 Nov. 2013).

As part of my research, I spoke with two experts in the field of Serbian-Russian relations: Ivan Stankić[15] and Dragomir Kojić.[16] Stankić introduced two overarching themes which are the backbone of the relationship between the two countries. The first is that Serbian politics is run on emotions. This is a bold claim and may offend some, but Stankić explained his reasoning thoroughly. Serbian politics fall prey to emotions more distinctly than in other places, he asserts, because there has not been a sufficient development of political culture. Emotions were heavily employed in politics during and before Yugoslav times, and today there are still remnants of this approach.

(The) multi-party system only arrived 20 years ago. Before 2000 this was a Frankenstein system. So you didn’t have people living in a democratic society in order to have these democratic values. Before that we used a lot of emotions to decide things” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013).

Serbia/Yugoslavia’s past leaders, Milošević, Tito, and the kings, are concrete examples, he says. Serbia’s political culture is still in transition to democracy from totalitarianism. Under totalitarianism, strong leaders were able to rule over this territory by inciting emotions in their constituents. “We are not rational, [we are] more emotional. When you decide who you’re going to vote for, you don’t take a look at their program, [or] how they’re going to raise taxes or not.” He continued that it’s much easier to gain votes if you mention Kosovo or Serbia’s Slavic ties with Russia. To be rational in politics is a death sentence for your campaign. Stankić relates it to the emotional draw of nationalism in the 1990s, explaining that “on emotions you can easily drag people to do something for you. If they sit and think, they will maybe say no.”

The other expert I interviewed, Dragomir Kojić, agreed that Serbian politicians manipulated their constituencies through the use of emotions. He was aware that the use of emotions was successful in preventing the societal transformation which is necessary in order for Serbia to modernize and become a functioning European country. As Serbia moves closer to EU membership, Serbs have become afraid of losing their national identity as a consequence of conforming to the EU. The many conflicts and struggles in and around Serbia have created an atmosphere ripe for manipulation of emotions in politics. Kojić states, “it is much easier to play on simple, raw emotions than actually deal with the serious education that you have to go through so you can achieve transformation” (Interview, Belgrade, 19 Nov. 2013). For politicians, he says, taking the hard road is a difficult and unrewarding path.

Instead, Kojić reasons, politicians are willing to enter into deals which benefit their own personal interests and not the Serbian national interest. When asked for examples, Kojić responded with many. Among them were several key figures in Serbia who have enjoyed immense financial benefits from political deals. For example, he asserts, Ivica Daĉić, of the Socialist Party, who lead the negotiations of the sale of the nationalized Serbian gas company NIS to Russia in 2008 was “being paid off by the Russians” in negotiating the deal (Interview, Belgrade, 19 Nov. 2013). Kojić argues that now “he is invincible in this country because the Russians are actually keeping his back.” Kojic also asserts that Boris Tadić and Vuk Jeremić, the former president and the former minister of foreign affairs, “actually made deals…which included their getting huge accounts in Switzerland.” Relating this information to me made Kojić disheartened, and he asked nonchalantly, “You want more? Unfortunately we have loads of these.”

For Stankić, Vladimir Putin in Russia epitomizes the strong leader who capitalizes on emotions and can bring his country out of the ashes and back into glory; Putin is the leader whom Serbs can only dream of, and his popularity in Serbia indicates this. “If Putin could be a candidate for president in Serbia he would win like that (snap). His voice is well heard here,” he says. “He has big authority in Serbia” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). So for those who would like to align with Russia, Moscow will have influence. This is not lost on Putin, Stankić argues, and Russia employs emotions as a powerful tool of manipulation in Serbia. “They easily play on our emotions. They always remind us of [the] NATO bombing, of [the] breakup of Yugoslavia, [that the] tribunal in Hague is not fair against Serbia. But nobody asks the question: do they know that Russia was in favor when the tribunal was established?” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). According to Stankić, Serbia is still a country in transition and has yet to develop a solid national identity or national interest, and Russia will likely take advantage of this in Serbia for as long as possible. Russia employs emotions in Serbia because it is a successful tool, which it can use without having to explain itself or exert effort. Any more effort from Russia would harm its national interests by focusing time and attention away from the former Soviet sphere and outside of the Balkan NATO zone, which are Russia’s stated priorities (Clover, 2008).

Kojić expands upon this by explaining that, for a non-NATO country in Europe to be on friendly terms with Russia means that “the West doesn’t have a complete victory” (Interview, Belgrade, 19 Nov. 2013). He goes on to say that Russia is still recovering from its Cold War loss, and therefore “they need Serbia not to join the EU. Not because that is strategically important in any way for Russia. Simply as a flag that their interests have succeeded in prevailing [over] Western interests.” In other words, Russia’s friendship with Serbia may have more benefits symbolically than in any tangible ways, and Russia is willing to devote a certain amount of time, effort, and resources to preserve this relationship.

The extent of Russia’s interests in Serbia represents the second major theme outlined by Stankić when trying to understand relations between Russia and Serbia. On the surface, it appears that Russia has a solid interest in Serbia. Gazprom bought NIS, the construction of the Southern Stream pipeline has officially begun, and Russia supports Serbia’s territorial integrity regarding Kosovo. However, Stankić was able to affirm each of these points as conditionally within Russia’s interests. Russia bought NIS on the eve of Kosovo’s declaration of independence, heavily pressuring Serbia. Russia easily gained from this: NIS was sold cheaply, and there was a surge in interest in Russia after its support for Kosovo (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). Russia was able to exert minimal effort in Serbia with large returns. The Serbian gas infrastructure was sold at a bargain price, and only with the informal condition that Russia would not recognize Kosovo’s independence (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). The Serbian populace did not need to know about such a deal; the support for their alleged territorial integrity was enough to inspire friendlier feelings towards Russia. The construction of the pipeline, for Stankić, is directly correlated with Russia’s problems within its own sphere of interest, namely in Ukraine. Russia has recently had problems maintaining control over Ukraine, the country through which most Russian oil and natural gas flows into Europe. Russia’s power and strength are concentrated in its natural resources, such as energy, and if Ukraine cannot be a reliable transit route for Russia’s most valuable assets, Russia must find a suitable alternative. Serbia happened to be that willing alternative.[17] It is not an ideal location for Russia, and “if Russia keeps Ukraine under control, there won’t be South Stream…it’s too expensive…80% of [Russia’s] oil exports go through Ukraine” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). This calls into question Russia’s true intentions towards Serbia.[18]

Many Serbs feel as though they must choose between following Russia and following the EU. Others, aware they are being courted by both the East and the West, see Serbia as an important successor to Tito’s non-aligned Yugoslavia. Stankić mentions how these ideas have been present in Serbia since the time of Milošević: “Milošević wanted to inherit this image of Yugoslavia. He failed. But people’s mindset is still, we still think we are very important…We are not even [a] regional power” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). Those who have graduated from this perspective have generally chosen to belong to one of two extreme camps: Russophiles and Russophobes. In Stankić’s own research, he found it difficult to obtain an objective opinion on Russia. Depending on what questions he asked, he would be labeled immediately as a lover of Russia or the contrary. “None of the extremes like the middle part. The Russophiles don’t like it because it represents Russia as a normal state with its own national interests…All sides want to emphasize one side of the story.”

Kojić also noticed that the discourse surrounding Russia was mainly split between two extreme positions, but he claimed that using Serbia’s historical ties with Russia to develop an opinion regarding Russia’s interests in Serbia is unfounded. Both extreme positions are probably incorrect, as “the truth lies somewhere in between. The truth of what Russia did is not really important anymore. Especially in history that goes further than the Second World War. We live in a post-Second World War system” (Interview, Belgrade, 19 Nov. 2013). As I found out in my interviews, however, Kojic’s position was held by some but not all of my participants.

Data Collection and Results

They [Russians] are even better than us. We drink more than they drink. We have more violence than they have. – Bojan (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013).

- Data on the History of Russian and Serbian Relations

Many of my participants did not have a solid grasp of Serbia’s history with Russia much before the 20th century, although it was suggested during a few of my interviews, such as with individuals from the Social Democratic Union, that history going back further than that is irrelevant to modern politics. To some, Russia and Serbia have a very limited history of natural alliance. According to Julijana[19] of the New Party, “the last Russian emperor was Nicolai who entered the First World War because of Serbia and that was, I believe, the last time that Russia will do anything for Serbia just because they are natural allies” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). One of the only other moderate answers came from Democratic Party member Đorđe, who was not convinced that Russia provided much help: “Russia has never provided adequate support to Serbia, except during the bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 by NATO” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013).

Most respondents provided more fervent opinions. Pavle, from the United Regions of Serbia (URS), started by explaining how liberation efforts from the Red Army were not very helpful during the Second World War. After WWII, the “USSR had planned to control Yugoslavia like all other Eastern European countries behind Iron Curtain. That plan didn’t work,” he says (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 27 Nov. 2013). He goes on to mention how Russia’s support of Slobodan Milošević was harmful to the people of Serbia in the 1990s. Others, such as Goran from the Liberal Democratic Party, had heard stories of disappointment about the lack of Russian help in the 1990s: “From stories of that time…people expected that Russia will intervene and defend us. There were stories that they would help our military” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia 18 Nov. 2013). Although his knowledge of history was limited, it seemed that his perception of Russia consisted of unmet expectations.

Some interviewees had no complaint about any historical interaction between Serbia and Russia. One of these people was Aleksandar, from the Democratic Party of Serbia, who recognized that Russia’s and Serbia’s interests did not always coincide, and did not blame Russia for any of its actions that may have had a negative effect on Serbia. To him, Russia helped sufficiently in WWI, the First Serbian Uprising, and more. So when asked about Russia’s behavior in 1878, he remained positive. “The main Russian interests in that time would serve Bulgaria…Perhaps the Serbs did feel betrayed, but in international politics, it’s all about interests” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). Although Russia was weak in the 1990s, things changed when Putin came to power. Aleksandar says, “Russia was strong and Russia is capable of protecting Serbia far more than it used to in the 90s” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013).

Bojan, from the Progressive Party, pushed this even further, blaming any Russian “failings” to support Serbia on Serbia itself. In his opinion, even the best allies will not support a wayward country. He explains: “We have such help from Russia, but we didn’t have it in 1999 because we were in a problem…no country will help you if you are a bad country” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013). However, Bojan believes, almost every Serb is aware that in the future Russia will be there to protect and serve Serbia’s interests. “You will not hear from any Serbian, he will not say that we do not believe that Russia can save us and Russia will always help us, you can hear that from every side” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013). Although this did not correspond with other answers I received, the Progressive Party was the current ruling party, so such beliefs may have more prominence in Serbia than was reflected in my interviews.

- Russia as an International Actor in the World and in the Balkans

Views of the interests of Russia in the world and in the Balkans today varied somewhat among my interviewees, though many people agreed that Russia today is concerned with economics and geopolitics. The LDP’s Mirjam thinks that today it is all about Russian power. “I think they want to be the strongest country, and the most independent country…They want to be a lone strong country…like Putin; he is a lone strong man” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). Andrej of the New Party agrees when it comes to Russia’s relations with Serbia today: “In my opinion, the relations between Serbia and Russia are now based on Russia’s profit rather than on historical bonds” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 24 Nov. 2013). Aleksandar of the DSS believes that “protection today is influenced by historical ties,” but remains convinced that Russia is following its own interests (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). This is demonstrated through the energy sector: “Russia is using its [energy] potentials in Europe in order to influence the European point of view on certain issues,” Aleksandar says.

Almost all of my respondents, both from the left and the right, agreed that Russia believed Serbia to have geostrategic importance. For instance, Teodor from the Progressive Party: “Politicians from Russia need Serbia because they want to have influence as much as they can on the Balkans” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 21 Nov. 2013). Goran (LDP): “[Russia] needs a partner in Europe who will spread [the] influence of Russia” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). Julijana (NP): “[Russia has] to position themselves on the Balkans” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). Đorđe (DS): “The main interest of Russia is Serbia’s strategic location…Serbia is located exactly in the middle between East and West” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). Some interviewees alluded to the fact that Serbia is not a member of NATO, but is an EU candidate country, and saw this as a viable reason for Serbia’s geostrategic significance to Russia.

Russia’s power in the international arena was threatening to some respondents, but inviting to others. To Bojan (SNS), it was almost a unique Russian characteristic. “Russia has something that most countries in the world don’t have and that’s authority in the country and also in the world,” he said (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013). Most people did not believe that Russia, despite its strength and perceived connection with Serbia, had much influence in Serbian politics. Aleksandar (DSS), who had mentioned earlier in his interview that Russia intended to influence other countries in the world, did not believe that this pertained to Serbia. When I asked him if this influence was present in Serbia, he replied, “not that much. The first major cooperation between Serbia and Russia in the past two decades was regarding Kosovo, [and]…it was just mutual cooperation, mutual interest” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). Still, some did think that Russia had influence in Serbian politics. Andrej (NP), for instance: “There is [a] big influence of Russia in Serbia because people here believe in [the] friendship and [the] historical bonds of our nations. Our politicians believe in that too, so that has [a] big influence on domestic policy” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 24 Nov. 2013). He goes on to suggest that Serbs may have unreal expectations of Russian support, stating, “I strongly believe that Serbs believe in Russia more than Russia is willing to help and contribute.”

- Russia and Serbia: 200 million

Only two participants did not recognize any shared cultural heritage with Russia. One of them was Petar from the Alliance for Vojvodina Hungarians, who did not even mention a cultural connection, although he viewed Russia as an important Serbian ally (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 21 Nov. 2013). Pavle (URS) explicitly negated any similar culture with Russia, or the importance of any: “I don’t see any more importance with Russia than with other European nations” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 27 Nov. 2013). Julijana (NP) agreed that culture is important when considering Russia, but noted that cultural ties with Russia were likely to be exaggerated. “They are important, but we can say that we have cultural ties with France or some other country…our ties with Russia are made to seem much more important than they really are” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013).

For a few others, cultural ties with Russia represented the backbone of Serbia and Russia’s relationship. For example, Teodor (SNS) thought he would be rebuked for denying such ties, saying: “In Serbia people will tell me I am a fool if I say no. Serbia has [a] big tradition with Russia, considering its history, culture, religion and let’s say politics” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 21 Nov. 2013). Teodor’s colleague in the SNS, Bojan, likened Serbs and Russians to one people united in history and culture: “We have [a] strong Slavic heritage and we have a strong background since all time because basically we are one people. We have the same connections and the same origin” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013). A couple of times during the interviews, an old Serbian joke was highlighted that reflected this very opinion: Serbia and Russia = 200 million. The populations of both countries are combined because the people are one and the same (the population of Serbia and Russia together is actually less, around 155 million).

The Orthodox religion was often cited as the fundamental shared cultural characteristic. Goran (LDP), for example, does not like it, but admits that it is true: “when you look at the constitution, we are a secular state, but the Serbian Orthodox Church has a big influence on the population” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013).

Even those who disliked most of Serbia’s relations with Russia, like Jovan (SDU), acknowledged the significance of a shared Slavic heritage: “I don’t see anything bad in those cultural relations. I think that that’s the part I would like to see more than the political part” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). In a growing world, perhaps Serbs take comfort in knowing there is a big country out there with which they can find similarities. Đorđe (DS) articulates this well: “It is always good to know that you are not alone, that there are people around who have the same customs, and who believe in the same way” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013).

- South Stream Pipeline: A gift or a scam?

November 24, 2013 marked the beginning of a major Russian project in Serbia, one that is mired in controversy and produced conflicting opinions among people I interviewed. This was the beginning of construction of the Southern Stream pipeline, which will bring Russian gas to Europe via Serbia. Like a few others, Aleksandar (DSS) was firm in his belief that Serbia benefited not only from this construction, but also from the sale of Serbia’s gas company, NIS, to Russia’s Gazprom: “[NIS] is pretty much the biggest investment and is a good investment.” He thinks that perhaps this investment will jumpstart more much-needed investment in Serbia by Russia. “[The] pipeline brings stability and a bigger presence of Russia in Serbia, and actually the whole region. And we are hoping for more Russian investments in [the] Serbian economy” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). There were, however, more people who thought Serbia had been somewhat duped in the NIS deal. Mirjam (LDP) said that selling NIS to Gazprom was almost a crime allowed by Serbian politicians. “NIS, the gas, [was] very cheap selling, like they are stealing from us. But it is not a thing for Russia, it is our politicians,” she says (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). This response was unique in that it did not blame or praise Russia, but suggested that Serbian politicians were perhaps manipulated by Russia.

Although energy was the main topic of discussion, Russian trade and investment were often mentioned in passing during the interviews. All of my participants were aware that Russia was not Serbia’s top investor, and many of them stated that they expect more investment by Russia in the future. Jovan (SDU) felt that not only did Russia invest little in Serbia, but that economic relations with Russia were actually costing Serbia money. “[Russia pays] lower taxes for using our resources than other countries do. We don’t get anything from them. Except losing money. And it’s billions” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013).

- Serbia: Caught in the middle?

When asked who respondents believed was Serbia’s most important ally, the European Union was an immediate answer for seven out of eleven participants. Julijana (NP) stresses that this is so because “Serbia is traditionally a part of Europe and will always be a part of Europe,” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). Andrej (also NP), is somewhat skeptical of naming anyone as an ally of Serbia. His view is that there are no true allies. The EU may be called an ally at times, but you “can’t count on anyone because they all work out of interest” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 24 Nov. 2013). Mirjam (LDP) again had an opinion unlike the rest of my interviewees when I asked her who Serbia’s most important ally was. To her, the United States’ democratic and liberal values represented the ideal that Serbia should try to achieve. She knew that her opinion differed from that of others, but “it is the most democratic country in the world …and we need to be something like that” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013).

Right-oriented parties were more likely to see Russia as an ally than left-oriented ones. For Petar (AVH), an alliance with Russia gives Serbia a powerful friend: “Serbia needs [a] strong ally country in the UN, connected to the Kosovo problem” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 21 Nov. 2013). Aleksandar (DSS) agreed that Russia was Serbia’s main ally, but quickly added that “every cooperating state is an ally” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). Aleksandar was the only one who was completely against Serbia joining the EU, and he related this to how much Serbia attempts to “bridge the gap” between East and West: “Serbia wants so much to enter the EU, it forgot its own interests.” While both members of the Progressive Party also stressed cooperation between eastern and western countries, it was Bojan who declared that Serbia’s partnership with Russia was more than an alliance.

Politically, an ally has its own certain interests, and they protect their own interests. But Russia didn’t just protect its own interests, they protected even Serbian interests, when Serbia was a normal country, and didn’t have problems…So I think Russia is not our ally, it is even more than an ally…The common oil company in the Balkans was [Putin’s] favor to Serbia. A loan for Serbia, cheap money for Serbia, was his favor to Serbia. Military agreement was his favor to Serbia. Gazprom in football clubs was his favor to Serbia. Paying debt to other countries from [the] Balkans was his favor to Serbia. And so on and so on,” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013).

For no one else was the devotion to Russia as strong as it was for Bojan.

Serbia has had a tense relationship with NATO following the 1999 bombing campaign. Thus, entering NATO is not a particularly desirable possibility for Serbia. This feeling has been encouraged by Russia, a country that has traditionally felt threatened by NATO expansion. Thus, Jovan (SDU) feels that “if we join NATO, they actually have official threats…they will look at it as an attack” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013). This might be related to the already strong NATO presence in the Balkans, explains Bojan. “In the Balkans, every country is a member of NATO and just Serbia is not. It is neutral, and that is important for Russia” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013).

This neutrality was alluded to in many of my interviews. When asked what Serbia’s position was in Europe, the overwhelming answer was that Serbia was somewhere in the middle. Petar (AVH) said that Serbia shared common ground with both “sides”: “Serbia belongs to Western economic aspects; in turn it belongs to the East ideologically and culturally” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 21 Nov. 2013). Bojan (SNS) thought that Serbia had inherited Yugoslavia’s strength as a non-aligned country. “[Non-alignment] is an idea from the past which we have today,” and a little later, “in the Balkans Serbia has the most influence. Even [Albania] cannot imagine a Balkan community without Serbia” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013). Jovan was one of the few who was adamant in his declaration of Serbia’s Western identity. “Serbia belongs to the West in the 21st century,” he proclaimed, “And that’s the only reasonable and logical thing as a country of Europe” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013).

- Vladimir Putin and the Kosovo Question

A specific reason why many Serbs consider Russia to be an invaluable ally is that it has refused to recognize Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence. This refusal is seen by some to be the main reason why Serbia has not relinquished the last of its claims of sovereignty over Kosovo. However, the respondents did not agree on whether Russia was successful or not in preventing Kosovo’s independence. For some, like Aleksandar (DSS), “Kosovo was that dispute where Russia showed its muscles in international relations” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 17 Nov. 2013)[20]. Bojan (SNS) agreed and noted that although Serbia will probably have to recognize Kosovo in the future, “we are the last country who will recognize Kosovo, and Russia will be the first country before us” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 Nov. 2013).

Members of the LDP questioned Russia’s support for Serbia’s claim on Kosovo. For Mirjam, this support hinged on the NIS deal with Russia, and for this “we are really hoping for them to be on our side in that ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ story” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). Goran believed that “Russia is an important player in the world scene, but I don’t think Russia will sacrifice its relations with other key players like the US, EU, and others just to defend [the] Serbian position in [the] Kosovo issue. For now, that goes quite correct because Russia does not lose anything from defending [the] Kosovo position, just gaining” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013).

Vladimir Putin’s popularity was explained by his support in regard to Kosovo and also his ability to return Russia to the forefront of international relations and reestablish Russia as a formidable power in the world. According to Goran (LDP), “if Yeltsin was a symbol of Russian weakness, [Putin] is a symbol of Russian power” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). It may even be a weakness of people in Serbia to be attracted to strong leaders like Putin, explained Julijana (NP). “People like strong people, like dictators, who will be capable of bringing greatness to its nation” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 18 Nov. 2013). Perhaps, for Serbs, Putin’s transformation of Russia represents what they can only hope for in Serbia.

Conclusions

“Does Russia want to be seriously examined in Serbia? Or do they want to remain this distant unknown mystery? If we put aside all emotions, Russia will remain naked. Pure national interest and pragmatic” – Stankić (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013).

It is possible to draw some conclusions, as well as point out inconsistences between the answers I received in the non-expert interviews and the information I gathered in the literature and in my expert interviews. My most consistent finding was that, as Stankić and Kojić predicted, interviewees’ answers were at times fraught with emotion and represented one of the two extremes (either pro-Russia or anti-Russia). Questions about the history of relations between Serbia and Russia were simple to analyze in this way. My hypothesis, that interviewees would be uninformed about historical details, was only partially true. Knowledge of pre-19th century history was present, but not very detailed. This history was often interpreted differently by different people, even when they stated the same facts. I found that conservatives were likely to know more history about relations with Russia than liberals. This should not be surprising, given my interview with Stankić, in which he mentioned that new historical details in relations were “discovered” when Serbia wished to acknowledge Russia’s benevolence. Stankić specifically mentioned an occasion when Dmitri Medvedev came to visit Serbia: “Suddenly Dačić[21] is talking about 500 years of history. We are discovering some Russian figures in history who helped Serbs” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). Conservatives were also more likely to forgive Russia’s past when its actions did not benefit Serbia. The fact that liberals were generally less informed about history is not surprising either, as they were more inclined toward the EU and were therefore less likely to think that historical relations between Russia and Serbia were important. Unless, of course, the respondents were fiercely anti-Russian, and then it seemed that their knowledge of history was sufficient to pinpoint Russia’s failings.

Questions about Russian interests and positionality produced some very interesting results. The expert hypothesis about emotional influence was both true and false in some respects. It was false because many of my participants were well aware that Russian interests were based on economy, geopolitics, and regional power. However, some of the more conservative participants were likely to think that these interests did not apply when Serbia was considered. Other ways in which Stankić’s hypothesis was true were represented in the lack of depth of some of the answers I received. For instance, most of my interviewees did not think that Serbia may fall outside of Russia’s sphere of interest (as Stankić reasoned). Instead, a few of them felt, like Kojić, that Russia may be glad to have a friend outside of the NATO zone. None of them recognized, at least explicitly, Stankić’s reasoning that Russia’s main interests were focused on the former Soviet states crowded around its massive borders. Likewise, the idea that Russia could be using emotional triggers as political manipulation was not mentioned in the interview responses. However, respondents were aware that Serbs have a traditional mindset in regard to how they respect their leaders. This came across when questioned about Putin’s popularity. Nearly all of my interviewees gave similar answers for why Putin has such a following in Serbia. Mostly, it was because he was a symbol of strength and rebirth. In Serbia, participants answered, people like strong leaders able to produce strong nations.

As for the motivations behind Serbian and Russian relations today, answers varied, even among liberal and conservative participants. Some people believed that relations today, no matter which form they took, have fundamentally developed as a result of cultural ties between the two countries. According to Stankić, this is the rhetoric that Russia would like Serbs to believe, as it relies heavily on emotion. Other respondents appeared more objective, believing that Russian interests in Serbia may be influenced by culture, but are motivated by economics. Stankić agreed with this motivation when he asked, “what is the rebirth of the Russian state in the 21st century?” He answered his own question: “Pragmatism and economy” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). The fact that political party did not determine which answers would be given shows this Russia-supported rhetoric has come to cross party lines.[22]

Since Kosovo is a political issue in Serbia that sparks strong emotional responses, this topic is very important for supporting Stankić’s hypothesis. Members of the LDP felt that Russia’s support for Kosovo directly correlates to the sale of NIS, and that Russia is not willing to jeopardize its relations with the West over support for Kosovo. The remainder of the answers from interviewees was largely split along extreme lines. Conservatives believed that Russia’s refusal to recognize Kosovo’s independence bid was invaluable for Serbia. Liberals were more likely to believe that this action by Russia either carried little weight or had done nothing to prevent Kosovo’s independence.

Extreme perspectives again dominated in the discussion of economics. Russia is either robbing Serbia or it is the Serbian godsend. There was very little in between, although it is interesting to note that both sides realized Russia is a strong investor in Serbia, even if not the top investor. This mirrors Kojić’s analysis and the statistics I found in the literature. Conservatives even mentioned that a major critique of Russia would be the lack of investment in Serbia, although most were hopeful that this was changing due to the construction of the South Stream pipeline. Only one participant mentioned that the pipeline was being built in Serbia as a response to Russia’s ongoing conflicts with Ukraine, an issue that Stankić emphasized heavily.

There were not as many extreme opinions pertaining to the subject of culture. All but two of my interviewees believed that not only were there cultural ties between Serbia and Russia, but that these were important and should be maintained and improved. The way this idea permeated both “sides” is valuable for further research, because it could mean that those who are anti-Russia do not think culture is affecting politics. This is in stark contrast to the ideas proposed by Stankić.[23] Although many Serbs believe they have many cultural similarities to Russians, Stankić believes that Serbs have much more in common with regional territories in the Balkans than with Russia: “People believe that we are more similar to Russians than to people in Bosnia. I used to live in Russia, my best friend was a Croat. This mindset is a bit different. I have friends in Russia but we don’t share much in common” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). If it is true that Serbs have more in common with their neighbors, then this constructed similarity with Russia could inspire false ideas about the relationship between the two countries. When examining this perceived likeness of Serbs and Russians, I can hypothesize that this idea may be related to Serbia’s search for its own national identity as a relatively new state in the Balkans. Serbia, trying to differentiate itself from its neighbors, looks to Russia as a guiding light for its development. Although this has at times been beneficial to Serbia, Russia’s assistance has not been consistent enough throughout history to warrant such assurance.

Regarding Serbia’s positionality in the world, the answers I received were very similar to conclusions in the literature I reviewed on the subject. Most participants, on the “left” and on the “right,” believed that it was Serbia’s prerogative to remain neutral and straddle the borders of the East and the West. The remaining answers, as in the poll reviewed in the literature, were split between moving closer to the EU or to Russia. Of those who valued Serbia’s declared neutrality, few likened it to the position developed in Tito’s non-aligned Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, as Stankić mentioned in my interview with him, the idea that Serbia is the successor to non-aligned Yugoslavia, and that it is capable of possessing the same power and influence, is a normal and typical perception of Serbia’s position in the world today. In my interviews, none of the participants explicitly likened Serbia’s neutrality to the non-aligned Yugoslavia, and many, with political views that would otherwise put them at odds with Tito’s government, would likely deny a direct connection. However, they also apparently see that with a position of neutrality, a small country like Serbia can hold a fair amount of geopolitical power, and any knowledge they have of Tito’s Yugoslavia would likely support that position. Thus, a connection may exist, if only on a more subconscious level.

Several broad conclusions can be developed about the perceptions and knowledge of the political party youth whom I interviewed. As was frequently mentioned, I received highly polarized responses from participants. This could be because Serbian politics are heavily influenced by emotion. It would be inaccurate to conclude that the perceptions of the participants were not based on facts and knowledge, but it is clear that the same knowledge was frequently interpreted differently by different people. As for an overall conclusion about whether Russian influence is positive or negative in Serbia, the fact that my participants were largely liberal does not allow me to make such concrete conclusions, though I can say confidently that cultural ties with Russia are perceived positively and have an effect on politics. It is clear that improved relations between Serbia and Russia have helped produce a generation of politically-minded youth with various opinions toward Russia. Serbia’s well-being depends on its citizens perceiving these relations objectively. It will behoove them to understand their limitations and also realistically assess their allegiances, especially if Serbia would like to increase its respect and position within the international community.

Limitations of Study

Aside from my own personal biases, there are other limitations to the data I was able to collect and analyze in my studies. The first limitation concerns my target population. Clearly, age parameters influenced my results, and increasing my age range would likely have broadened and diversified my data. Conducting my interviews in English also limited my population to people who already had some kind of connection, even if only literary, with the West. Talking with members of political parties ensured that I received politically-minded and somewhat informed answers, but it is also possible that these answers were more likely to be influenced by the leaders of political parties. My location was also a limitation. It is likely that people in Belgrade have different perceptions than people living in more suburban or rural areas of Serbia (although I did get a few interviews with people based in Vojvodina).[24] Finally, because it was difficult to arrange all of my interviews in person, I had to collect my data for many interviews over e-mail. Allowing people to think more about their answers and use the internet makes the information collected from these interviews less spontaneous than desired. However, the alternative was having no data from some of the major political parties.

Recommendations for Further Study

Because my research was largely concerned with general and broad perceptions, the opportunity to continue research into a more specific field is large. I am interested in the areas of economics and energy, as they are largely the drivers behind the relations between Serbia and Russia both now and in the future. It would be useful to look more specifically at investment in the Serbian economy by different international entities and see how that investment correlates with the political relations between the relevant countries. In the area of energy, a problem with the South Stream pipeline that recently surfaced is that it does not meet all of the EU requirements. As Serbia intends to join the EU, it is important to follow EU regulations. Studying this and how it relates to the geopolitical importance of energy in international relations would be important and timely. I am also very interested in the connection between xenophobia and post-socialism, how Serbia’s connection with Russia might be a side effect of such tendencies, and how Russia is safe and glorified because it is “the same.”

Bibliography

Belgrade Centre for Security Policy. (2012). Citizens of Serbia between EU, NATO and Russia.Belgrade: Belgrade Centre for Security Policy.

Clover, C. (2008, August 30). Russia Anounces “Sphere of Influence”. Retrieved from Financial Times: online.

Cox, J. K. (2002). The History of Serbia. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Futura Publikacija. (2008). Nation as a Problem or Solution: Historical Revisionism in Serbia.Novi Sad.

Grinkevich, V. (2013, October 16). Mladic Defense Gets Ready for Attack. Retrieved from Voice of Russia: online.

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. (2013, April). Russia and Serbia. Helsinki Bulletin(93).

Heuberger, V., & Vyslonzil, E. (Eds.). (2006). Serbia in Europe: Neighbourhood Relations and European Integration. Vienna: Wiener Osteuropa Studien.

Hosmer, S. T. (2001). Why Milosevic Decided to Settle When He Did. Santa Monica: RAND.

ISAC Fund. (2010). Russia Serbia Relations at the beginning of XXI Century. (Z. Petrovic, Ed.) Beograd: ISAC Fund.

Judah, T. (2000). The Serbs: History, Myth, and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Yale University Press: New Haven.

MacKenzie, D. (1967). The Serbs and Russian Pan-Slavism 1875-1878. Ithica: Cornell University Press.

Novakovic, I. (2012). Neutrality in Europe in the XXI and the Case of Serbia. Belgrade: ISAC Fund.

Pavlowitch, S. K. (2002). Serbia: The History of an Idea. Washington Square: New York University Press.

The Delegate of the European Union to the Republic of Serbia. (n.d.). FDI in Serbia. Retrieved March 4, 2014, from The Delegate of the European Union to the Republic of Serbia: online.

Voice of Russia. (2013, October). Russian Patriarch Praises Orthodox Kosovo Serbs for Courage. Retrieved from Voice of Russia: online.

Vuksic, D. (n.d.). Serbia-Russia Military Political Relations in the Process of Solving Kosovo Issue and in the Future. Retrieved November 15, 2013, from ISAC Fund: online.

Zikovic, M. (2011). Serbian Dreambook: National Imaginary in the Time of Milosevic. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Interview Questions

- Age, education, gender, place of birth and place of current residence, position in political party.

- Who is Serbia’s most important ally?

- Is there a connection with Russia? Why?

- What is your knowledge about Serbia’s history with Russia? During the Ottoman period? The 19th century (1878, first Serbian uprising)? Between socialist Yugoslavia and the USSR? During the Yugoslav wars of the 90s? What is modern Russia like? What is Serbia’s biggest criticism of Russia?

- What is the importance (if any) of the cultural and religious ties between Serbia and Russia? In the past? Now?

- Is this connection beneficial to Serbia? To Russia? Why?

- What are Russia’s interests in Serbia?

- What is Serbia’s position in Europe? What is Serbia’s function between the East or the West?

- How do you view Serbia’s entry into the EU or NATO? How does this compare to Russia’s view of EU and NATO? How will Russia respond if Serbia joins the EU or NATO?

- How does Serbia and Russia’s relationship affect the issue of Kosovo? Does Russia have a consistent attitude towards Kosovo? (I then mentioned the Georgian Republics.)

- (How) Does Serbia’s relationship with Russia influence Serbia’s foreign and domestic policy? What are the benefits of the economic ties with Russia?

- How does Russia operate in the area of international relations?

- How do you view Russia’s position on human rights? How does the Serbian government view Russia’s position on human rights?

- How is Russia presented to the public? Do you think that there is a strong Russian presence in Serbia?

- What does Russia represent for the average Serbian citizen?

- What is the reason for Vladimir Putin’s popularity in Serbia?

Appendix 2: Political Parties in Serbia

In this section I will provide information on the major political parties, as well as some of the minor parties whose members I interviewed. This information provides insights into the influence of each party in the country and how their stated ideologies matched with the answers I received.

The Serbian Progressive Party, or in Serbian, the Srpska napredna stranka (SNS), is the political party of the current Serbian president, Tomislav Nikolić[25]. A conservative party, it split from the more conservative Radical Party to take a stance that was pro-EU integration. The party has many seats in the National Assembly[26], as well as a solid showing in the Assembly of Vojvodina[27]. Many of Serbia’s political parties are parts of coalitions, and the SNS shares one with the right-wing New Serbia. The membership of the SNS, as of 2012, was 300,000, and the party is known to cooperate with the Russian party United Russia[28].

The Socialist Party of Serbia[29] (Socijalisticka partija Srbije, SPS) is represented by current Prime Minister Ivica Dačić and is the party of Slobodan Milošević.[30] It holds seats in the National and Vojvodina assemblies[31]. It grew from the League of Communists of Serbia and represents ideas of Serbian nationalism, socialism, and post-communism. In 2012 its members numbered 120,000. This party is traditionally and officially more sympathetic to Russia than the other parties.

Serbia’s previous president, Boris Tadić[32], was also president of the Democratic Party, or Demokratska stranka (DS). It is now the main opposition party and holds half the seats in the Assembly of Vojvodina and a number of seats in the National Assembly.[33] As a center-left party, its platforms are pro-Europe, social democracy, and liberalism[34]. In 2013 the party had a membership approaching 200,000. Their attitude toward Russia is ambiguous: they are more pro-European; however they do not renounce ties with Russia.

The Liberal Democratic Party, or the Liberalno-demokratska partija (LDP), split from the Democratic Party after criticizing then-president Tadić. It declares itself to be centrist, but is a strong supporter of Serbia joining the EU and NATO, Kosovo’s independence, and the improvement of LGBT rights in Serbia. However, in 2012 membership was just 90,000, and the party has weak representation in both the National and Vojvodina assemblies[35]. This party is one of the main opponents of increased ties with Russia.

Not to be confused with the Democratic Party from which it split, the Democratic Party of Serbia (Demokratska stranka Srbije, DSS) espouses nationalism, conservatism, Christian democracy, and Euroscepticism, with the firm belief that Kosovo should remain a part of Serbia. The party is led by former Prime Minister (2004-08) Vojislav Kostunica, has a membership of 100,000, and has seats in the National and Vojvodina assemblies.[36] This party is the most fervent supporter of a pro-Russian course in Serbia. It is actively advocating cooperation as an alternative to EU integration.

A party with a similar ideology is the center-right United Regions of Serbia (Ujedinjeni regioni Srbije, URS). With sixteen seats in the National Assembly, the party is based on regionalism, liberal conservatism, and Christian democracy. Its membership in 2012 was 220,000. This party is a descendent of the G17 plus, one of the most fervent proponents of the EU in Serbia. However, it does not express a negative attitude toward Russia.

The Social Democratic Union (Socijaldemokratska unija, SDU) is a small party which split from the Social Democratic Party in 2003. Its main ideology is social democracy and modernization of Serbia through integration with the EU. It holds just one seat in the National Assembly.

Serbia has a minority Hungarian population in its province of Vojvodina, and one of the parties representing them is the Alliance of Vojvodinian Hungarians (Savez vojvodjanskih madjara, VMSZ). The main ideology relates to regionalism, minority rights, and liberal conservatism. VMSZ is represented with five seats in the National Assembly and eight seats in the Assembly of Vojvodina.

I have also talked with people from one of the newest political parties in Serbia, the New Party, formed early in 2013 by former Prime Minister Zoran Živković (formerly a member of the Democratic Party). The party seeks to keep reforming and modernizing Serbia. The party has yet to take part in any elections, but is set to compete in the next set of regional elections that will take place in Belgrade.[37]

Appendix 3: Foreign Direct Investment in Serbia

Appendix 4: Serbia’s Imports and Exports

Imports

CEFTA: Central European Free Trade Agreement

Source: The Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Serbia

Exports

Footnotes

[1] All participant and expert names have been changed [2] While in Belgrade, I was advised by Igor Novaković, a member of the International and Security Affairs Centre (ISAC) Fund, who oversaw my research and guided the direction of my study. [3] At the beginning of my study abroad program in Belgrade, I was introduced to several members of different political parties in Belgrade. [4] Entities with whom Serbia would like to strengthen relations: EU, US, China, and Russia [Citation?] [5] The oldest participant was 30. [6] The Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires shared control over the territory today known as the Balkans. [7] When Russia led a pan-Slav war with Serbia against the Turks in 1876 to “avenge Kosovo,” the idea could have easily been to prepare for the war it entered into with Turkey only a year later. “Avenging Kosovo” refers to the highly symbolic Serbian defeat by the Turks in the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The battle was fought between the Turks of the Ottoman Empire and Serbia and its allies. Both the leader of the Turks, Sultan Murad I, and the leader of the Christian Serbs, Prince Lazar, were killed in battle. However, the myth of Prince Lazar’s death states that he sacrificed his life and his “earthly kingdom” for Serbia’s return to greatness in the future and its ability to inherit the “heavenly kingdom” (Cox, 2002, p. 30). [8] An interesting comparison can be made with another event in 2008, which was Russia’s recognition of the provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia as independent states. There are a few theories about Russia’s inconsistency in its idea of “territorial integrity.” First, Russia may not recognize Kosovo because the Western powers have refused to recognize Georgia’s breakaway provinces (Vuksic, p. 4). Alternatively, Russia’s interests in maintaining influence over Georgia may have been more important than abiding by international laws of sovereignty and integrity (ISAC Fund, 2010). Russia often notes that after Georgia attacked these provinces, they were no longer liable to such laws. [9] As in the Balkans, Serbia is one of the few countries not in NATO.in its region. [10] Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, UNMIK (Kosovo), Moldova, Albania, and Serbia [11] Reference Appendices 3 and 4 for the respective graphs of Serbia’s foreign direct investment, imports and exports. These graphs show the different levels of trade and investment with the EU, Russia, and others. [12] Greece may be debatable as an eastern country, but it is geographically further east than Serbia and it is an Orthodox nation. [13] In Albania’s case, an eastern country with the good will and support of the Western world. [14] The Russian attitude towards NATO is more often than not perceived to be entirely negative. But what we must remember is that Russia has been a major cooperative partner of NATO for many years (Petrović 2010, p. 99). Among non-NATO members, it sends the most troops on NATO peacekeeping missions, and has even cooperated with NATO in Bosnia (1994 and 1996), on the Dayton Peace Agreement (1996), and with KFOR (Kosovo Force in 1999). [15] Stankić works for the Diplomatic Forum and wrote his master’s thesis on Serbian-Russian relations. [16] Kojić works for the ISAC Fund [17] Kojić agrees that the Southern Stream pipeline is only being constructed because of problems with Ukraine, and he is concerned that it may interfere with Serbia’s application for EU membership. During our interview, he said that “just yesterday we received information from [a] European agency for energy that our contract with Russia is not in accordance [with] EU regulations. So if we want to keep going towards [the] EU we have to adjust it. Of course the Russians do not like that” (Interview, Belgrade, 19 Nov. 2013). [18] Stankić gave me another interesting idea about Russia’s interest in Serbia: “If Russia really loved to help Serbia, they would accept this offer to Serbs in Kosovo to become citizens of Russia” (Interview, Belgrade, Serbia, 28 Nov. 2013). Apparently, Kosovar Serbs sent this request to Moscow a couple of years ago but have not received a positive answer. Stankić believes this is because it would require Russia actually to be invested in the safety and security of Serbs in Kosovo. [19] All participant and expert names have been changed. [20] When subsequently asked about how this relates to Russia’s recognition of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Aleksandar mentioned that it was a problem of international law. Recognizing Kosovo’s independence is against international law (as it is to recognize the Georgian provinces), but the case of Georgia was different because Georgia attacked these provinces and Russia only came to their aid. [21] Serbian Prime Minister [22] An interesting side note is that none of the respondents explicitly acknowledged that Serbian politicians are involved in profitable yet shady deals with Russians, and that this economic motivation may be an underlying cause for the success of the relations between the two countries. This was a point strongly emphasized by Kojić. [23] The data I collected is not specific enough to warrant a concrete conclusion. [24] Two of my answers came from the autonomous province of Vojvodina. Vojvodina is historically closer to the West (it was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire) and has a large Hungarian minority. Its multiethnic and multicultural character make it prone to advocate minority rights. Its largest city is its capital, Novi Sad, and the population of the entire province is 1.93 million. One of my participants came from Novi Sad, and another came from one of the smaller cities in the province. [25] Elected in 2012 [26] Serbian parliament, with 53 of 250 members [27] Separate parliament for the autonomous province of Vojvodina, with 23 of 120 members [28] Conservative party of Russia’s current president Vladimir Putin [29] Despite multiple efforts with multiple contacts, I was unable to interview a member of this party. [30] Serbian leader during the wars of the 1990s until 2000 [31] 25 of 250, 12 of 120, respectively [32] 2004-2012 [33] 57 of 120, 41 of 250, respectively [34] The party is also associated with the reform-minded Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić, who was assassinated in 2003. [35] 12 of 250 and 1 of 120, respectively [36] 21 of 250, 4 of 120, respectively [37] I was not able to interview anyone from the super-conservative Serbian Radical Party(Srpska radikalna stranka, SRS) because my advisor stated categorically that no one from that group would talk to me. Current president Nikolić is a former member (and with current Deputy Prime Minister Vučić formed the Serbian Progressive Party), and the party is led by Vojislav Šešelj, a man convicted of war crimes in Bosnia and sent to the ICTY in 2003. The party emphasizes nationalism, social conservatism, right-wing populism, anti-globalism, Russophilia, and Eurosceptism. I would have been very intrigued to interview someone from this far-right party, but unfortunately it was not possible. The party holds no seats in the National Assembly and five in the Vojvodina assembly.