Every year hundreds of thousands of travelers make the pilgrimage to the breath-taking shores of Lake Baikal in Siberia. Unfortunately, the awe-inspiring natural beauty of Baikal’s vistas may not last forever. Scientists are studying the effects that climate change and other environmental degradation in the region will have on the thousands of local plant and animal species, including the humans that work, play, and live on Baikal’s shores. It is important, for the welfare of all interested species, to invest in research and to work to protect the local ecosystems.

The work of scientists will come to no use, however, if corresponding actions are not taken by ordinary citizens. But what motivates individuals to take action? To answer this, we will use the framework of “space” and “place.” “Space” can be understood as the physical aspects of our surroundings, both natural (rivers, mountains, lakes, etc) and human-built (cities, roads, factories, etc). Meanwhile, “place” includes not only the physical features, but also the socioeconomic, political, historical, and cultural characteristics of an individual’s environment. This paper will develop a basic analysis of space with a contextualization based on the concept of place specifically for residents of the Baikal region.

Specifically, this research seeks to answer the following questions: 1) What are the space-based relationships between environmental degradation and human beings’ everyday lives; 2) How do residents perceive that relationship and; 3) Is there a link between the perceived risks of environmental degradation and participation in environmental protection initiatives? To explore these questions, scholarly publications were consulted and an eleven-question survey taken from local residents of the Baikal region. The publications show the development of industries in the Baikal region, the main health consequences connected with environmental degradation, and the history of environmentalism in the region. However, the texts also present the opinion of the author in some way. For this reason, we also focus on the survey, which aims to capture the current opinions of the residents of the Baikal region. While most respondents were college students at Irkutsk State Linguistic University (ISLU), and thus the responses cannot be said to definitely encompass the views of the overall population, its results are still useful, particularly as a gauge of what is usually one of the most politically and socially active segments of any local society (see Appendix A and Appendix B).

The research shows that there are real threats to local human health from environmental degradation and the majority of respondents report concern about this. However, there are also a variety of blockades which prevent participation in environmentally-based organizations and events. Thus, this paper will provide a cursory history of the development of relationships between humans and Baikal’s natural resources and an overview of the modern uses of Baikal. The possible consequences of human industrial activity on local ecosystems and human health are then assessed as are actions taken to mitigate the risks and protect the environment through current local initiatives. Finally, the main portion of this study will examine the results of the survey in this context.

Contextualizing Baikal: A Brief History of the Lake’s Settlement and Development

The historical context of the settlement and development of the Baikal region provides a better understanding of the place and space relationships. Lake Baikal, listed in 1996 by The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage site, is “the largest (by depth and volume), oldest, and most biotically rich lake on Earth.”[1] The fresh water, fish, berries, and other resources around Baikal have allowed the permanent inhabitation of the area for the last 30,000 years.[2] In the thirteenth century, peoples from Mongolia settled in the western and eastern regions of Lake Baikal, eventually creating the Buryati nation.[3] In the seventeenth century, the major immigration to Baikal was of Northern Russian peasants.[4] They developed an “integrated economy based on a combination of crop-growing and stock-breeding alongside hunting, fishing, carrier’s trade and nut-gathering.”[5]

Increased development and subsequent urbanization of Eastern Siberia also changed the rate of resource exploitation. With the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad, for example, starting in the 19th Century and the industrialization that came with Stalin’s Five-Year Plans in the early 20th Century, the harvest of raw materials from the Baikal area increased dramatically as it became easier to transport them to other locations in Russia and the USSR where demand was growing.[6]

Today, the most developed regional industries are timber and wood-processing, pulp and paper, mining, fuel, metallurgy, power engineering, machine-building, chemicals, oil, and food production.[7] Tourism is also a major contributor to the economies of such cities and towns on Baikal as Lestvianka and Olkhon.

These industries influence both space and place. From a spatial perspective, tourism incentivizes ecological preservation because that industry is dependent on the surrounding natural beauty. In fact, at local universities, eco-tourism programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels are growing in numbers and popularity.[8] Not all industries encourage conservation, however. The lumber industry, for one, directly leads to at least some amount of deforestation. In these ways the industrial development of the region serves as a framework for the space and place relationships of between the environment and human activity.

Consequences of Human Industrial Activity

Environmental change compounds with socioeconomic factors in influencing the overall health of the modern peoples of the Baikal region, a perfect example of the combination of place and space.[9] A report produced by the Russia’s State Commission on Baikal, “Protection of Lake Baikal and Environmental Management in the Baikal Region,” cites a “strict” dependence “between the levels of technological pollution of the atmosphere and illness of the population in industrially developed cities.”[10] Because of the far-reaching personal ramifications of health problems on one’s professional and personal life, questions of health tend to provide incentive to participate in environmental protection actions.

The same state report states that Baikal region scientists have established a direct connection between diseases of the digestive and nervous system as well as some types of cancer and the micro-elements in the drinking water.[11] Access to clean drinking water illustrates well the role of place as it is vital for human life. Without means or knowledge about purifying water, e.g. with a faucet purifier, families are at high risk of contracting diseases from the water supply. A middle-to-upper-class family with greater education on water cleanliness and the financial means to invest in water purification, will thus likely have a lower risk of contracting such diseases than their counterparts in a lower socioeconomic and education bracket. The conditions of the space, e.g. water sources, combines with socioeconomic level and education to create inequality of place, leaving one family more susceptible to illness than another because of social factors and their environment.

Air quality is another key factor of public health. Of the list of Siberian cities with high levels of air pollution, three of the top four are cities around Baikal: Angarsk, Bratsk, and Irkutsk. The World Health Organization reports that poor air conditions increases the burden of “respiratory infections, heart disease, and lung cancer” and estimates that, globally, urban outdoor air pollution causes 1.3 million deaths yearly.[12] Although smoking, which is popular in Russia, also increases respiratory problems “exposure to air pollutants is largely beyond the control of individuals and requires action by public authorities at the national, regional and even international levels,” the WHO asserts.[13] If action is not taken, to avoid pollution-related health risks, residents of areas with poor air quality must resort to moving away if they wish to escape it. Mobility, however, is also often determined by outside connections and education (which can offer more job opportunities) and wealth (which can provided the investment a move requires). Thus, social issues compound with environmental issues to influence public health.

The beauty of a place can also have an effect on health although it generally “deals with well-being and health gain,”[14] as a report from The Institute of Human Health and Ecology in Chelyabinsk has argued. In economic terms, a WHO-produced report states, decreasing the beauty of a tourist-dependent area can lead to “loss of tourist days; resultant damage to leisure/tourism infrastructure; damage to commercial activities dependent on tourism; damage to fishery activities and fishery-dependent activities; and damage to the local, national and international image of a resort.”[15] Litter is common contributor to degradation of natural beauty, particularly when there are few or inadequate trash receptacles.

All together, these reports answer the first question of our study, showing strong connections between place and space effects of environmental degradation and its negative affects on society and individuals.

Environmental Actions Already Taken in the Baikal Area

Ecological problems in Siberia became globally recognized in the 1980s and 1990s.[16] In the 1990s, regional environmental scientific studies were conducted and many non-profits, funded both domestically and internationally, emerged to protect and develop Lake Baikal.[17] This greatly increased the social and/or political group’s ability to participate in environmental actions. A look at some these actions will help us to answer our third question: Is there a link between risk of environmental degradation and participation in environmental protection initiatives?

In the early 1990s, American and Soviet scientists, led by an American planner, George Davis, completed a two-year study of Baikal and recommend a comprehensive land use plan for the Baikal Basin called “The Lake Baikal Region in the Twenty-First Century: A Model of Sustainable Development or Continued Degradation?” in 1993.[18] This report proved instrumental in the government’s officially contracting Davis’ non-profit, Ecologically Sustainable Development, Inc and USAID “to develop several pilot land use projects in the Lake Baikal region.”

To produce the report, “the planning team members needed to understand and respect local cultural traditions and folklore”[19] as there was a strong local connection to place. Local leaders were crucial in the planning and implementing projects. Local advisory committees worked on mapping features important to native traditions and lifestyles. Overall, the outside team members facilitated, but did not dominate the process, allowing the local communities to guide the regional strategy for land use and development.[20] This level of support that the local communities gave indicates a strong connection to the issue at hand, that of environmentally-friendly development, and that local communities perceived those issues as crucial to their wellbeing. In fact, later, in 1995, the Oka Declaration, issued by a group of indigenous people, reaffirmed “local support for the comprehensive program for the entire Lake Baikal Basin,”[21] which included the proposed “Okinsky National Park and Culturally Protected Landscape.”

Collaboration with USAID also resulted in the formation of the Great Baikal Trail project. The Great Baikal Trail (GBT) is now a prominent organization working to protect Baikal by promoting ecotourism and environmental education in Irkutsk and around Baikal. Among other initiatives, during the summer, GBT facilitates the construction of environmentally-friendly hiking paths around the lake and, during the winter, holds a weekly club which plans year-round events. GBT is just one of a plethora of other organizations including the All-Russian Society for Nature Conservation, Baikal Wave, and The Scientific-Ecological Center.[22]

Social factors can also affect levels of participation in these groups. For example, the main office of GBT was, as of Spring 2012, on the outskirts of town, far away from any bus stops. Access to public transportation, commute time, and general mobility could thus influence an individual’s attendance of GBT events. The handicapped and elderly could be particularly excluded from participation as they constitute the least mobile populations of Irkutsk, especially considering the city’s lack of handicap-friendly facilities and transport. Environmental movements must find a balance with making their events more accessible to all while still focusing the majority of their attention on recruiting volunteers who can readily participate. The survey of this project focuses on this population.

Survey on Environmental Degradation and Protection

While background information can contextualize the relationship between man and the environment, texts present the opinions of the author. For this reason we require additional up-to-date that attempts to capture the current perceptions of residents of the region to understand their reactions to information concerning environmental threats. This study does not claim to represent the views of the entire populace of the Baikal region. Instead it serves as a cursory overview of current participation in environmental activism and perceptions of climate change, focusing mainly, though not exclusively, on local university-aged youth.

- Methodology

The survey aspect of this research encompasses all three questions of this research but gives particular insight into the second and third questions: 2) How do residents perceive the relationship between environmental degradation and their everyday lives and; 3) Is there a link between risk of environmental degradation and participation in environmental protection initiatives?

The survey consisted of eleven questions: eight multiple choice, and three free response. They are geared to provide insight into: 1) How frequently those living in the region participate in environmental activism on average, 2) Their perception of common impacts of environmental degradation and 3) How prepared the individual is to work for the protection of the environment of Baikal. The entire survey may be found in Appendix A and Appendix B of this paper.

There a few questions which might require some commentary. The fifth question, for instance, is a free response and simply asks respondents to list ways in which degradation of the environment impacts their daily lives. For the purposes of this study, a free response question was appropriate here because the ways in which environmental degradation affects an individual’s surroundings and day-to-day life can be so greatly varied that it would be irresponsible and inaccurate to attempt to give choices in a multiple choice question. The only personal information requested in the survey come with question eleven, which asks for the age, education level, and profession of the respondent and is included in order to gage whether those characteristics influence the responses to the other question.

The survey was distributed in person with paper copies as well as electronically using Surveymonkey.com as a platform and Facebook.com, Vkontakte.ru, and CouchSurfing.org as distribution methods. The online version received 71 responses between March 20th and April 4th. Paper copies were handed out throughout Irkutsk, mostly at the Irkutsk State Linguistic University and the Irkutsk State University. As a result, the majority of the respondents were students between the ages of 18 and 22. The advantages and disadvantages of this will be reviewed later in the discussion section. The survey was also given out at bars, to guests of the host family, and to high-school aged students of the English language.

- Results and Analysis

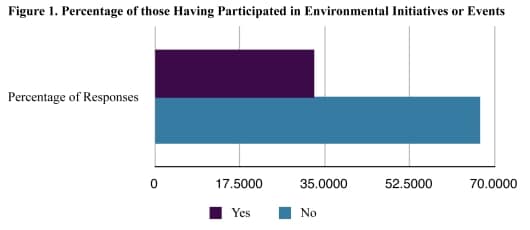

Overall, the data show that respondents do perceive climate change and environmental degradation as threats and that a large proportion of them are prepared to participate in environmentally themed events and/or groups. However, only 32.9% had participated in an environmental event (see Figure 1).

Organizations that the respondents participated in included The Great Baikal Trail, The Tahoe-Baikal Institute, Green Peace, and unspecified school- and university-based groups. It is likely the actual percentage of participants in environmental events is lower as a disproportionate number of respondents to the survey are active members of the Great Baikal Trail. To the third question, over 64% responded that they participate in environmental activities never (32.6% of total) or less than once per a year (31.9% of total). About 22% reported participating between two and four times per a year. About 14% responded that they participated more than five times per a year, with 7.1% of that participating more than ten times per year (see Figure 2). However, most participants who frequently participate are members of the Great Baikal Trail. The majority of other applicants report no or rare participation. Thus, we can infer that it is likely that the majority of residents of the region do not participate in environmental events or groups.

The next set of survey questions indicates that despite the low involvement in environmental activities, most citizens view environmental degradation and climate change as a risk. An overwhelming majority, 89.7%, answered that they felt that climate change presents a risk. 81.3% feel that human activity causes global warming. Only 8.6% felt that climate change was not a risk. The remainder of respondents report not having a clear idea of what climate change was (see Figure 3).

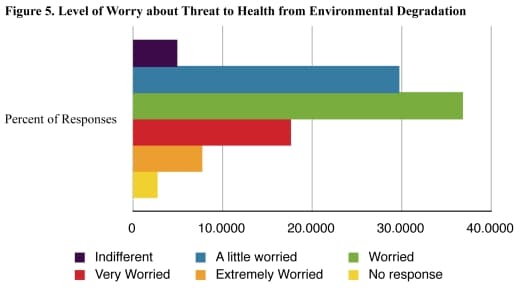

When asked to list ways in which environmental degradation affects their daily lives, most point to air quality, the ability to exercise outside, and illness related to air pollution. These responses align with the reports of the health risks discussed in Section III. Additionally, 38.5% of respondents reported seeing air pollution as the biggest threat to their health, with the second highest being the “other” category, to which a number of applicants responded that they felt more than one or all were risks (see Figure 4). When asked how concerned they were about this, however, only 7.8% answered that they were extremely worried. 36.9% stated that they were simply worried and 29.8% reported feeling a little worried (see Figure 5). Only five percent reported being unconcerned. Thus, we can see that most respondents see climate change as a threat, but, for most, that threat is not one that causes great concern in their everyday lives.

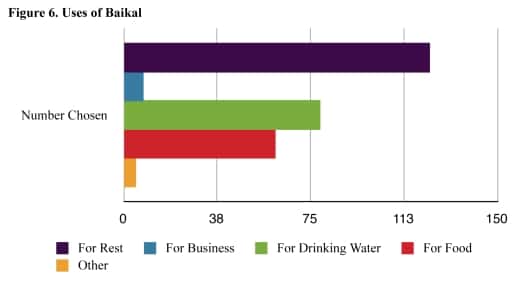

Most respondents stated that they most often use Baikal for leisure activities. Of online applicants, almost 85% stated that this was their primary use for Baikal. The least popular was business with only 7% of online applicants choosing that option (see Figure 6). This suggests that, in trying to recruit for environmental protection activities, focusing on the negative impacts environmental degradation would have the pristine views and popular locations around Baikal would likely be most fruitful.

Finally, when asked if they are prepared to participate in environmentally-themed events, 82.3% responded in the affirmative. Of that total, 39.7% reported that they were ready but did not know how. For the most part, those who answered negatively said that they did not have time. Only 2.8% answered that they were not prepared because they did not consider it to be important (see Figure 7). So, while most people are not yet involved, many are ready to participate but need clear instruction on ways to do so. Increased visibility for environmental movements might help galvanize support for them.

- Discussion: Challenges and Disadvantages of the Survey

Overall, this survey serves as a starting point for other research and gives some insights into participation in the environmental protection movement in the Baikal region. However, there are some disadvantages of the survey which must be taken into consideration. Firstly, the age range of the survey takers is narrow with mostly college-aged students responding. In theory, however, this age bracket is the most disposed to take action in any society as most students generally do not have the burden of taking care of a family or working.

A bigger concern is that most respondents come from similar backgrounds. Most of the hand-written surveys were distributed at Irkutsk State Linguistic University or Irkutsk State University. Additionally, those invited via Facebook and Vkontakte were also mostly students or former students of those institutions. Because of this, the results of the survey should not be taken as representative of the entire population of Irkutsk, but rather of a particular segment of the larger population.

Secondly, after receiving questions from those completing the survey it appears that there was some confusion about the rating system for question nine. In the typical Russian grading system, five is best and one is worst. Question nine was written to imply that one was best and four worst, however. While, in general, the phrasing of the question should have clarified the rating system, it is likely that many incorrectly ranked their responses. Without being able to control every survey and with no means of finding out which were incorrectly completed, we have no way to correct any errors. Future research may avoid this mistake, however, and hopefully reach a broader section of the population.

Further possible topics for research include differences in the perception of climate change regionally around Baikal and between socioeconomic levels. Differences within age, race, and education level should also be considered.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both text analysis and the survey provide answers to the three questions of focus of this research. Firstly, both space and place relationships to human beings’ everyday lives and environmental degradation do exist. Specifically, environmental degradation and climate change compound place-based social issues related to public health. Given the severe effects poor health can have on both an individual’s professional and personal activities, it is logical to assume that these place and space relationships are strong. The survey responses circumstantially support this as respondents report both specific health-based threats and generally high levels of willingness to participate in environmental actions.

Secondly, the survey and texts show that perceived threat from environmental degradation in general have long existed, specifically pertaining to health. However, these perceived threats are not currently translating to increased rates of participation in environmental organizations. The survey results show that one reason for this disconnect is a lack of knowledge on the ways to become involved. Environmental organizations could try to increase their visibility, seek more diverse ways to clearly advertise when, where and how individuals can become involved, and facilitate participation of a broader spectrum of volunteers, for example by having online tasks for less mobile individuals who cannot attend meetings.

Space and place analysis is an effective framework to assess both the physical and the social impacts of environmental degradation and the response to those effects via participation in environmental initiatives. This approach can be utilized in the future to further explore the physical, social, and political ramifications of environmental degradation. In particular, questions that this research revealed which demand more investigation within the space-place model include, but are not limited to, differences of opinion by age group, the role of environmental education, and differences in participation based on socio-economic level. Continued research is imperative as we move forward into a world with increased climate change and other environmental threats to both nature and our livelihoods.

The author of this analysis, Ingrid Korsgard is currently perusing degrees in Russian as well as Community and Global Health at Macalester College in Minnesota. Her research was performed in Irkutsk while based in that city and while attending SRAS’s Siberian Studies program.

Works Cited

Anonymous. “First Settlers of Baikal.” BWW.irk.ru: Comprehensive Data about Lake Baikal in Siberia. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <http://www.bww.irk.ru/index.html>.

Anonymous. “Irkutsk oblast, Russia (Irkutskaya).” Welcome to Russia. RussiaTrek, Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://russiatrek.org/irkutsk-oblast>.

Brunello, Anthony J, et al. Lake Baikal: Experience and Lessons Learned Brief. N.p., 27 Feb. 2006. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <http://www.ilec.or.jp/eg/lbmi/pdf/02_Lake_Baikal_27February2006.pdf>.

Moore, Marianne V, et al. “Climate Change and the World’s “Sacred Sea”—Lake Baikal, Siberia .” BioScience 59.5 (2009): 405-417. Macalester College Library. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233952366_Climate_Change_and_the_World’s_Sacred_Sea-Lake_Baikal_Siberia>.

Plumely, Daniel R. “Traditionally Integrated Development Near Lake Baikal, Siberia.” Cultural Survival. N.p., 26 Mar. 2010. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <http://www.culturalsurvival.org/ ourpublications/csq/article/traditionally-integrated-development-near-lake-baikal-siberia>.

Volkov, Serguey. Around Baikal. Ed. Natalia Bencharova. Trans. Bertie Playle. Olkhon Island: Nikita’s Homestead, n.d. Print.

Williams, A T, K Pond, and R Phillips. “Chapter 12: AESTHETIC ASPECTS .” Monitoring Bathing Waters -A Practical Guide to the Design and Implementation of Assessments and Monitoring Programmes. Ed. Bartram Jamie and Gareth Rees. World Health Organization, 2000. N. pag. PDF file.

World Health Organization. “Air Quality and Health.” World Health Organization. WHO, Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs313/en/>.

“БЦБК – Проблема Длиной в 40 лет.” Гринпис России. Гринпис, 3 Feb. 2010. Web. 9 Dec. 2011. <http://www.greenpeace.org/russia/ru/campaigns/baikal/193753/>.

Думова, И И Механисмы Управления Региональным Природопользов. Новосипирск: n.p 2001. Print.

Федерация России. Государственны Центр Экологических Программ: Правтельсвенно Комиссии по Байкалу. “Влияние Качества Оркужающей Среды на Здоровье Населения .” Охрана Озера Байкал и Обеспечени Рационального Природопользов в Байкльском Регионе. Москва: n.p., 1997. Print.

Руденко, Г.B., и Е.B. Бирюкова. “Экологическое Образование и Туризм в Байкальском Регионе.” Инетеллктуальные и Материальные Ресурсы Сибири: Материалы Региональной научно–практической конференции. Иркутск: Идеательство БГУЭП, 2007. N. pag. Print.

Тюмасева, З.И., Маркова А.С., Машкова И.В. “Здоровье человека и окружающей среды–в аспекте общего эколого–валеолгического образования студентов педагических вузов.” Экология. Образование. Здоровье. Материалы международной научно–практической конференции. Челябинск: Институт здоровья и экологии человека ЧГПУ.

Appendix А: English Variant of the Survey

- Have you participated in any ecological organizations?

a. Yes

b. No - If you answered yes to the first question, which organizations did you work with? _____________________

- How many times do you participate in an event related to the ecology per year?

a. Never

b. Less than once a year

c. 2-4 times a year

d. 5-10 times a year

e. More than 10 times a year - Do you believe that climate change is a threat?

a. I do not know what it is

b. No, I do not think it is a threat

c. Yes, and I believe human activity has contributed to global climate change

d. Yes, but I do not think human activity has contributed to global climate change - How does the degradation of the environment influence your everyday life (i.e. You cannot exercise because of air pollution)? Please write your variants.

- How concerned are you about the effects of degradation of the environment, on your day-to-day life that you listed above?

a. Unconcerned

b. Somewhat concerned

c. Concerned

d. Very concerned

e. Extremely concerned - What do you see as the biggest threat to your health from degradation in the environment?

a. I see no connection

b. Water pollution

c. Air pollution

d. Litter on the streets

e. Degradation of natural beauty

f. Increased UV rays from the depleted ozone layer

g. Other_____________ - How do you use Lake Baikal? Please circle all that apply and explain in the space provided

a. For relaxation/ recreation.

b. For economic reasons, e.g. business connected with Baikal.

c. For drinking water.

d. For food (e.g. fish).

e. Other______________ - Please rank your most valued uses of Baikal from 1 to 4, 1 being most valued.

a. Recreation

b. Business

c. Drinking water

d. Food - How prepared are you to participate in environmental protection events for Baikal?

a. Not prepared because I do not see it as important

b. Not prepared, no time

c. Prepared, but I do not know how

d. Prepared - Please give the following information on yourself.

Age_________ Education ________ Profession _________

Appendix B: Russian Variant of Survey

1) Участовали ли вы когда либо в работе экологических организаций?

- да

- нет

2) Если вы ответили утвердительно на первый вопрос, то с какими органицазцими вы работали или вы работаете?

3) Сколько раз в год вы принимаете участие в мероприятиях, связанных с экологией?

- Никогда

- Реже, чем раз в год

- 2-4 раза в год

- 5-10 раз в год

- более чем в 10 раз в год

4) Считаете ли вы, что изменение климата представляет угрозу?

- Я не знаю, что это такое

- Нет, я не думаю, что это угроза

- Да, и я считаю, человеческая деятельность способствует глобальному изменению климата

- Да, но я не думаю, что человеческая деятельность внесла свой вклад в глобальное изменение климата

5) Как влияет ухудшение состояния окружающей среды на вашу повседневную жизнь (например: вы не можете заниматься спортом из–за плохого воздуха)? Пишите ваши варианты:

6) Как вы к этому относитесь?

- Равнодушно

- Несколько обеспокоены

- Обеспокоенный

- Очень обеспокоены

- Крайне обеспокоены

7) Какую вы считаете самую большую угрозу для вашего здоровья от деградации окружающей среды?

- Я не вижу никакой связи

- загрязнение воды

- загрязнение воздуха

- Мусор на улицах

- Деградация природной красоты

- Увеличение УФ-лучей от обедненного озонового слоя

- Другое_____________

8) Как вы используете ресурсы озера Байкал? Обведите необохдимое.

- Для отдыха

- Для бизнеса

- Для питьевой воды

- Для продуктов питания (например, рыба)

- Другое______________

9) Чем является для вас Байкал? Выстройте рейтинг от 1 до 4.

- Для oтдыха

- Для бизнеса

- Питьевая вода

- Пища

10) Насколько вы готовы участовать в мероприятиях по защите экологии Байкала?

- Не готов, потому что мне не важно

- Не готов, нет времени

- Готов, но не знаю как

- Готов

11) Укажите, пожалуйста, ваше данные:

Возраст:_______ Образование:______ Профессия:________

Footnotes

[1] Moore, Marianne V, et al. “Climate Change and the World’s “Sacred Sea”—Lake Baikal, Siberia .” BioScience 59.5 (2009): 405-417. Macalester College Library. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233952366_Climate_Change_and_the_World’s_Sacred_Sea-Lake_Baikal_Siberia>.

[2] Brunello, Anthony J, et al. Lake Baikal: Experience and Lessons Learned Brief. N.p., 27 Feb. 2006. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <http://www.ilec.or.jp/eg/lbmi/pdf/02_Lake_Baikal_27February2006.pdf>.

[3] Anonymous. “First Settlers of Baikal.” BWW.irk.ru: Comprehensive Data about Lake Baikal in Siberia. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <http://www.bww.irk.ru/index.html>.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Irkutsk oblast, Russia (Irkutskaya).” Welcome to Russia. RussiaTrek, Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://russiatrek.org/irkutsk-oblast>.

[8] Руденко, Г.B., and Е.B. Бирюкова. “Экологическое Образование и Туризм в Байкальском Регионе.” Инетеллктуальные и Материальные Ресурсы Сибири: Материалы Региональной научно–практической конференции. Иркутск: Идеательство БГУЭП, 2007. N. pag. Print., pp 44.

[9] Федерация России. Государственны Центр Экологических Программ: Правтельсвенно Комиссии по Байкалу. “Влияние Качества Оркужающей Среды на Здоровье Населения .” Охрана Озера Байкал и Обеспечени Рационального Природопользов в Байкльском Регионе. Москва: n.p., 1997. Print. pp 44

[10] Ibid 38

[11] Ibid 40

[12] World Health Organization. “Air Quality and Health.” World Health Organization. WHO, Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs313/en/>.

[13] Ibid

[14] Тюмасева, З.И., Маркова А.С., Машкова И.В. “Здоровье человека и окружающей среды–в аспекте общего эколого–валеолгического образования студентов педагических вузов.” Экология. Образование. Здоровье. Материалы международной научно–практической конференции. Челябинск: Институт здоровья и экологии человека ЧГПУ.

[15] Williams, A T, K Pond, and R Phillips. “Chapter 12: AESTHETIC ASPECTS .” Monitoring Bathing Waters -A Practical Guide to the Design and Implementation of Assessments and Monitoring Programmes. Ed. Bartram Jamie and Gareth Rees. World Health Organization, 2000. N. pag. PDF file.

[16] Думова, И И Механисмы Управления Региональным Природопользов. Новосипирск: n.p 2001. Print. pp 14

[17] Руденко, Бирюкова, 346.

[18] Plumely, Daniel R. “Traditionally Integrated Development Near Lake Baikal, Siberia.” Cultural Survival. N.p., 26 Mar. 2010. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. <https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/traditionally-integrated-development-near-lake-baikal>.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid

[22] Руденко, Г.B., and Е.B. Бирюкова; note that the Russian for these organizations is as follows: All-Russian Society for Nature Conservation (Всероссийского общества охраны природы), Baikal Wave (Байкальская Экологическая Волна), ; and The Scientific-Ecological Center (Научно–методический экологический центр)