The most important issue in Armenia’s regional relations is the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Armenia is a landlocked country flanked by two historical adversaries, Turkey and Azerbaijan, with which it has closed borders. Due to this, Armenia focuses on maintaining relations with Georgia and Iran for secure trade routes. It also has ongoing tensions with Turkey over the 1915 Armenian Genocide.

Although it entered the post-Soviet period hopeful to join the EU, Armenia’s geographical position, geopolitical limitations, and an active Russian and Iranian presence have led it to focus on becoming a transport corridor between Iran and Russia. Working towards peace in the region would allow Western countries access to faster transport routes between the Black Sea and Persian Gulf as well as more direct routes to the energy-rich Caspian Sea while allowing Armenia to develop in more geographical directions.

Domestically, Armenia is challenged by its rugged terrain, inadequate transport routes to its vulnerable south, and struggles to maintain stable and effective development policies.

Armenia’s Domestic Security Issues

Food Security: Armenia imports nearly double the amount of basic foodstuffs that it produces, including for grains, meat, eggs, and vegetables. Domestic agriculture is dependent on imported fertilizers and equipment. Farms are often run by single families and are small and inefficient. Greater consolidation, more mechanization, and better land management practices are all cited as needed to improve Armenia’s food security. Agriculture directly accounts for 12% of Armenia’s GDP and employs about 25% of the workforce.

Energy Security: Armenia produces excess energy, which it exports mostly to Iran. About 40% comes from natural gas and another 30% comes from the Metsamor nuclear power plant. The fuel for both is imported from Russia via Georgia. About 30% of Armenia’s energy is produced by hydro plants along Armenia’s fast-moving rivers.

Metsamor was built in 1979 without primary containment structures. It is aging and although it was supposed to be decommissioned years ago, it remains pivotal to Armenia’s energy security. Armenia is seeking to replace about half its capacity with the Aig-1 Solar Plant, which has already been delayed several times, but is due to be completed by a Saudi construction company in 2025. Many experts agree that Armenia could be energy independent by realizing its renewable energy potential and investing in better transmission infrastructure.

Armenia has attempted to diversify its gas supply with pipeline built to Iran, but that has remained non-operational for many years. Gazprom controls both pipelines and it is rumored that the company wants to prefer Russian gas for as long as possible. However, it’s also possible that US sanctions against Iran have also kept Armenia from demanding that the pipeline be activated.

Military: Armenia is one of the most militarized societies on Earth with military expenditures approaching 4.5% of GDP and with 2.5% of the population serving as active duty personnel. This is a direct result of the ongoing conflict with Azerbaijan.

Armenia makes very few of its own weapons and instead has an inventory of older Soviet-built hardware and imported hardware from Russia, Europe, and the US.

Armenia is outstripped in military spending by its rival Azerbaijan, which won due in part to its effective use of drones and because Armenia was slow to adapt to this technological innovation.

Since the war, Armenia has lost the security of a sizeable buffer state between its vulnerable south and its enemy and now instead has a long, shared border and only a small corridor of land to connect it to Nagorno Karabakh which it is still pledged to defend.

Economic Security: Armenia’s transition to a market economy has been difficult, held back by the country’s relative isolation and restricted access to global markets (caused by its closed borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey). Concerns over regional conflict make it challenging to attract foreign investment. Government policy affecting economic development has also been haphazard and government-led infrastructure projects have often run over budget or failed to materialize.

Armenia has struggled with high unemployment rates, especially among youth and women. 2021, the year after the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, was particularly hard with official unemployment reaching 19.5% and an estimated 3-4% of the population emigrating that year to seek opportunity abroad.

Personal remittances (sent by Armenians working abroad back to family members at home) accounted for about 11% of GDP as of 2022. Although halved from a 2003 high of 22%, this is still a high number and indicates that economic opportunity must grow in Armenia for the country to retain its own workforce. The vast majority of these funds in 2022 came from Armenians in Russia.

The service sector accounts for 55% of Armenia’s GDP and employs 35% of the workforce. Tourism, IT, finance, energy, and telecoms are major industries in this sector.

Industrial Base: Armenia’s mountains hold significant amounts of iron, copper, molybdenum, lead, zinc, gold, and silver. of gold, uranium, and mercury. The Kajaran Mine in Syunik is the largest in Armenia as of 2021 and primarily produces copper, for which there is currently a global shortage. It feeds the Zangezur Copper-Molybdenum Combine, which processes the metal and is by far Armenia’s single largest taxpayer.

Industry and mining contribute about 27% of Armenia’s GDP and employ about 17% of the population. Mineral exports account for about 25% of Armenia’s exports with gold and copper being some of the most valuable. Cut diamonds, imported mostly from Russia and processed in Armenia, are another major export.

Manufacturing in Armenia is dominated by agricultural processing: processed foods, drinks, textiles, and tobacco processing (some tobacco is grown in Armenia, but far more is imported from places like South America, India, and Zimbabwe for processing and export to other Caucuses and Middle Eastern states. Several processing companies including Grand Tobacco Armenian-Canadian Joint Venture Ltd., are ranked among Armenia’s largest taxpayers and employers.

Transport for Trade and Defense: For both trade and defense, all sections of a country should be well connected by transport. International markets should also be accessible, preferably by seaport.

Armenia is landlocked and none of its many rivers are commercially navigable. Railroads connect most major cities in the north but interconnectivity and efficiency are hampered by mountainous terrain and the enormous Lake Sevan. The south is minimally connected via a line that runs through Nakhchyvan, a territory controlled by rival Azerbaijan. Roads, the least effective transport for trade and military, are generally well developed and well maintained and connect all major parts of the country.

Armenia and Iran have long pushed for a new rail link from the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea through Armenia, which would provide the shortest possible route from those bodies of water. This would bolster trade and fill a transport gap in Armenia’s vulnerable south, through which Azerbaijan desires a corridor to reach Nakhchivan. The rail project lacks funding, in part because of security issues and in part because a line has recently been completed linking Iran to Moscow through Azerbaijan.

Urban vs Rural Development: To be prosperous and secure, economies should be diversified in production and spread equitably over the country.

Yerevan houses some 40% of Armenia’s population. The capital also accounts for some 60% of GDP and about 45% of industrial production. Much of this is due to how the region was developed under the Soviets, but the government is finding it hard to push development to other parts of the country.

Gyumri, at 120,000 in Armenia’s northwest, is Armenia’s second largest city. All others are considerably smaller.

Much of the population lives in a band formed by this agricultural heartland stretching through the country’s center. It includes the Ararat Valley, a large swath of flat land south of Yerevan, which is dominated by orchards and viticulture, and Gegharkunik, north of the capital and surrounding the gigantic fresh water Lake Sevan, which irrigates grain and potato fields and waters livestock.

Climate Change and Water Security: Armenia relies heavily on freshwater resources from the Araks and Vorotan Rivers, which are vulnerable to changes in precipitation and temperature. With rising temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns, Armenia may experience water scarcity, which could impact agricultural production, energy generation, and public health. The source of Vorotan is in Nagorno-Karabakh and the Araks originates in Turkey, creating additional geopolitical risks for Armenia’s water security.

Effects of Russia’s “Special Military Operation”* on Armenia: Since Russia began what it calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine, an estimated 65,000 Russians have immigrated to Armenia, or about 2% of the overall population. These immigrants are mostly young and many are entrepreneurs or skilled workers. Russians are now likely Armenia’s largest single ethnic minority at perhaps 2.5-3% of the population.

Although the arrival of these immigrants has led to higher inflation, particularly in Yerevan, they have also helped plug the emigration crisis and brain drain the country was facing. New businesses have been launched and the country’s flagging IT sector has been bolstered by new talent and funds. With no shared border with Russia and no current ongoing conflict with Russia, these Russians have integrated relatively well in Armenia.

Armenia’s trade with Russia has risen by nearly 450% since 2020. Despite the fact that the country is relatively isolated, much of this trade is re-exported goods such as electronics and vehicles that have been affected by sanctions and companies leaving Russia in protest of the “operation.”

*part of the content of GeoHistory is produced in Russia, where there are laws restrictive of what current events can be called.

Armenian Politics in Brief

Armenia is a representative parliamentary republic. It was converted from a semi-presidential republic in late 2014 as part of a series of reforms. The president is now a figurehead who may not be a party member and may only serve one term. The prime minister is more politically powerful.

Armenian politics has been rocked by instability since the 2018 “Velvet Revolution,” sparked when Serzh Sargsyan, leader of the then-ruling Republican Party who spearheaded the 2014 reforms, was nominated to be prime minister after promising not to hold on to power after his presidential term ended. Opposition leader and journalist Nikol Pashinyan was then elected as prime minister and the Republican Party lost all its representative seats in the following election.

About two thirds of the seats in Armenia’s unicameral parliament, the National Assembly, are held by the centrist Civil Contract Party, led by Pashinyan. They have never published an official ideology and have oscillated between pro-EU and pro-Russia as well as pro-business and pro-labor policies, resulting in what many see to be muddled and ineffective policy making. Promised infrastructure programs are typically slow in development due to inefficiency and corruption.

Opposition alliances include the socialist-nationalist Armenia Alliance, led by former president Robert Kocharyan. Also in opposition is the I Have Honor Alliance, led by ousted former president Serzh Sargsyan, which supports conservative, nationalist policies.

Most Armenian citizens in recent polling name national security as their main concern. Most also consider the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh to also be a question of honor for Armenia. The economy is named as the second most pressing concern.

Azerbaijan’s quick victory in the second Nagorno-Karabakh war in late 2020 led to a political crisis in Armenia. This escalated to an open conflict between Prime Minister Pashinyan and the military, with the top brass and the opposition parties calling for Pashinyan’s resignation. Public confidence in the Prime Minister fell to about 25%. However, this is far more than any other politician possesses and thus Pashinyan remains in office and his party remains in power.

Armenia’s Regional Relations

Regional Cooperation: Armenia has been left out of many cooperation groups such as GUAM and infrastructure projects such as the North South Transport Corridor, all of which have favored Azerbaijan. Armenia’s relative isolation and its ongoing conflict with Azerbaijan makes building transport connections with Iran through Armenia riskier. A “3+3” regional cooperation format has been proposed that would unite the three Caucasus countries with Turkey, Iran, and Russia to resolve regional disputes. Such an arrangement might benefit Armenia. However, given the strained relations between many of the six counties, the format is likely unworkable.

- A map of Armenia’s major waterways within its region.

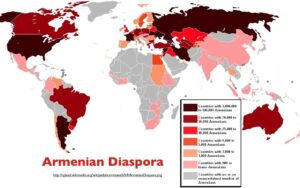

- A map of the Armenian Diaspora. Countries shown in dark red have between 100,000 and 3,000,000.

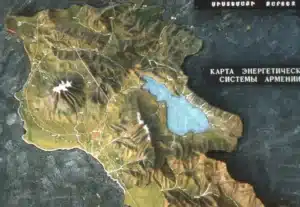

- This map detail shows the dominance of Lake Sevan and the Caucuses in Armenia’s landscape. Transport through much of the country is difficult.

Azerbaijan: Armenia has no diplomatic relations with Azerbaijan and the two have not had open borders since the fall of the USSR. They have fought two wars over the status of Nagorno Karabakh, an Armenian-majority region which has been de facto independent since 1994, but is still internationally recognized as being part of Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan – two corridors: Armenia’s last connection with Nagorno Karabakh runs through the Lachin Corridor. Azerbaijan is currently blockading that route, preventing all traffic and imports, including gas and food. Azerbaijan is demanding that Armenia finish its half of a new road through the corridor (Azerbaijan’s half is complete) and provide Azerbaijan expanded access to Nakhichevan through the Zanzegur Corridor, which runs through southern Armenia. Armenia wants to keep access restricted, fearing that it may lose control of its southern border and lose its direct access to Iran.

Turkey: Armenia has strained but improving relations with Turkey. Turkey closed its border with Armenia in 1993 in solidarity with its historic ally, Azerbaijan. Armenia has painful memories of the Ottoman Empire’s deportation of 1.2 million Armenians to the Syrian desert under horrific conditions in which most deportees died. Armenia calls this a genocide while Turkey denies that it was a systematic destruction of Armenians. Since the 2020 war, moves have been made to normalize relations, such as a 2022 announcement that air cargo connections would resume and that border crossings would open to third-country citizens “as soon as possible.” However, little progress has been made on these plans.

Georgia: Armenia maintains good relations with Georgia, the only country with which Armenia shares an open border with direct rail connections. More than 70 percent of Armenia’s cargo transportation goes through Georgia, including a gas pipeline from Russia. More than 100,000 ethnic Armenians live in Georgia, primarily near the Armenian border or in Tbilisi. Treatment of these Armenians and their lack of political representation is occasionally discussed but has not been a major issue to date. Georgia has supported Azerbaijan in its conflict with Armenia, but has not moved to sanction Armenia. Armenia has consistently voted against UN resolutions that recognize Georgia’s breakaway provinces as part of Georgia but, likewise, has not moved to sanction Georgia concerning the provinces.

Iran: Armenia and Iran have good relations, with rapidly growing trade despite not having a direct rail connection on their border. Iran wants to grow trade from $700 million in 2022 to as much as $3 billion in coming years. To do so, it supports more infrastructure between the two counties (although it has not moved to finance it) and a lasting peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan (although it has arguably balanced its stance between the two countries). Nearly all of Armenia’s excess energy production is exported to Iran. As many as 200,000 Armenians live in Iran, making them Iran’s largest religious minority, and many of the oldest Armenian churches, monasteries, and chapels are located in Iran. The whole area was long part of Persian Empires and/or the Armenian Empire. The Armenian minority in Iran have helped relations by acting as advocates for their state. They are appointed two out of the five seats in the Iranian Parliament reserved for religious minorities.

Relations with Larger Foreign Powers

Russia: Armenia has maintained a close relationship with Russia. Armenia is a member of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which includes Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Belarus. Russia is by far Armenia’s largest trade partner, absorbing about a quarter of Armenia’s exports, and supplying nearly a third of all imports, including almost all energy imports. Russia has helped fund the restoration of Armenian historical sites. The majority of remittances, now 11% of Armenian GDP, come from Armenians in Russia. Russia is one of Armenia’s biggest suppliers of weapons and Russia maintains a base in Gyumri, Armenia’s second largest city.

However, the relationship between Armenia and Russia has not been without its challenges. In 2018, Nikol Pashinyan’s election signaled a shift toward diversifying Armenia’s foreign policy with closer ties with the EU and the United States. The biggest strain to date has been the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, in which Russia mediated a peace that cemented Azerbaijan’s gains. Since, Russia has been seen as largely absent in mediating Azerbaijan’s blockade of the Lachin Corridor, which is preventing food and fuel from reaching Nagorno Karabakh.

US: The US has a large and politically active Armenian diaspora. At one point, the US was providing more financial aid per capita to Armenia than to any other country. The US has provided Armenia with military aid and training. However, trade between the two countries remains limited. Recent years have seen strain on the relationship as the US has maintained a neutral stance on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The US has also voiced concern over Armenia’s rising trade with Russia and its desire to act as a trade corridor between Russia and Iran, two traditional American foes.

China: Since the fall of the USSR, Armenia and China have maintained a cordial but limited relationship. China absorbs 11.5 percent of Armenia’s exports and supplies 14.5 percent of its imports, both significant amounts. Chinese contractors completed the North-South Highway that provides increased connectivity between Armenia and Iran. They were also due to build the North-South Railroad along a similar route before Armenia had to shelve the project for lack of funding. Although China did build a new $12 million Chinese cultural center in Yerevan, cultural and military ties between the two countries are limited. China has been largely neutral on Nagorno-Karabakh and backed the Russian peace deal that cemented Azerbaijan’s gains.

EU: Although most Armenians see theirs as a European country with European roots, relations with Europe have slowly regressed since Armenian independence. A Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) was signed in 2017 between the two, but EU membership has been largely forgotten since it was seriously discussed in the early 2000s. EU states are collectively one of Armenia’s largest trading partners and have provided significant financial aid and some military cooperation, mostly in demining activities and improving border management. The EU has also stayed largely neutral on Nagorno-Karabakh.

More about Armenia

Armenia: A Global People

The Modern Republic of Armenia lies in the turbulent south Caucuses. Although the Armenians as a people have existed for thousands of years, they have…

Armenia’s Foreign Policy and Security Issues for 2023

The most important issue in Armenia’s regional relations is the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Armenia is a landlocked country flanked by two historical adversaries, Turkey and Azerbaijan,…

Nagorno-Karabakh: The Volatile Core of the South Caucasus

The Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh is one of four frozen conflicts that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Legally recognized as a part of…

A Comparative Look at Coronavirus Responses in Eurasia

The global health crisis has changed life around the world, but in often very different ways in various places. Even countries located close to each…

Karabakh: Youth, War Zones, and Unrecognized Borders

The views expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of GeoHistory or SRAS. This fascinating interview is presented here as documentation of what…