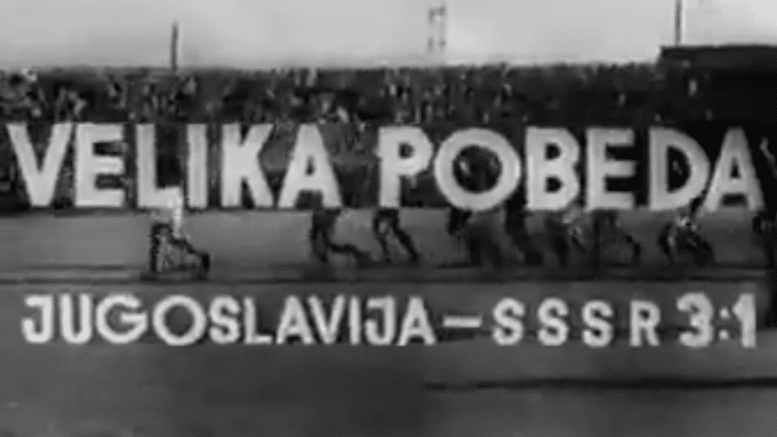

This project examines Yugoslav history between June 1948 and July 1952, beginning with the Tito–Stalin Split and ending with Yugoslavia’s symbolic football victory over the Soviet Union at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. While the split has been well studied politically, this paper additionally emphasizes its broader social impact, showing how the political rift resonated with ordinary citizens and why the Olympic football matches mattered to all segments of society. I argue that the split’s aftermath created economic hardship and tested national unity, making the victory both a political vindication for the authorities and a morale boost for the public.

On June 28, 1948, the Cominform expelled Yugoslavia, [1] accusing the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) of “nationalism.” [2] Tito’s insistence on independent decision-making clashed with Stalin’s sphere-of-influence policy. Stalin’s declared embargo against Yugoslavia caused an economic crisis, worsened by the 1950 drought. The sudden break with the USSR and Stalin, formerly revered as heroes and protectors of Yugoslavia, was psychologically impactful to Yugoslav society as well.

Against this backdrop, Yugoslavia’s Olympic win carried extraordinary symbolic weight. The victories were celebrated as proof that the state’s defiance of Moscow was justified. For the KPJ, it was a propaganda victory; for ordinary citizens, it was tangible evidence that their sacrifices had meaning.

Vladimir Dedijer, the premier Yugoslav Communist historian and Central Committee member, would state that “under normal political conditions that would have been an ordinary game. But in view of the conflict between the two countries, then at its peak, this game attracted the attention of all sectors of the populace.”[3]

In this paper, I will examine KPJ documents and memoirs to reconstruct elite opinions surrounding Yugoslavia’s expulsion from and subsequent isolation in the Communist world. Following this, I will utilize American foreign service documents to examine Yugoslavia’s need for economic assistance following the Split and the extent to which the average Yugoslav was sacrificing for the state’s independence from Soviet influence. Then, I will utilize memoirs of high-ranking Yugoslav communists and media accounts from Yugoslavia and abroad of the Olympic matches to examine how they were viewed within this political and economic context.

Historiography

Despite the Tito-Stalin Split’s lengthy historiographical record, there remains a lack of consensus on its causes. Most scholars agree on its role in refocusing Yugoslav foreign policy, as well as contributing to the creation of Yugoslav-style socialism, defined by self-governing workers’ councils and the incorporation of limited aspects of free market trading. Many scholars also agree that the split was not a product of doctrinal or Marxist-Leninist ideological differences, but rather of nationalism.[4] However, some scholars focus on other specific details. John Connelly centralizes Tito and his personality as the root cause of the split.[5] Marie-Janine Calic indicates Tito’s ambition to create a Balkan federation with Bulgaria and Albania as the primary cause. She also mentions Stalin’s fears of going to war over Greece, a state over which he ceded influence to Britain in the 1944 Percentages Agreement, and Tito’s support of the Greek communist guerrillas as a major sticking point in the Stalin-Tito relationship.[6] Yugoslav historians predominantly place the blame on Stalin’s shoulders. Vladimir Dedijer claims that Stalin sought a monopoly over Yugoslavia, seeking to make it economically subservient to the Soviet Union.[7] Milovan Djilas, a Yugoslav Politburo member, points to Stalin’s personal desire for control and is the earliest first-hand account to mention Stalin’s displeasure over Yugoslav support of Greek communists.[8]

In Cold War sport historiography, the Tito-Stalin Split is often oversimplified. Richard Mills, the leading scholar of Yugoslav football history, has two publications in which the split is mentioned. His monograph, The Politics of Football in Yugoslavia, devotes a sentence and a half to it, claiming that Stalin, in fact, had demanded the formation of the same Balkan Federation discussed above and Tito had refused. Mills, then, claims that Tito’s refusal caused the split, while not referencing the broader context of the refusal as cited by the above scholars. His article “Cold War Football: Soviet Defence and Yugoslav Attack following the Tito-Stalin Split of 1948” had earlier mentioned the same.[9]

Mills’ article also argues that the two matches themselves do not receive enough historiographical attention in Cold War sport history and that the 1952 Yugoslav victory was a pivotal Cold War sporting moment.[10] However, without the proper nuance and understanding of the political history of the Cold War, the true importance of the games is clouded. This paper will present the game within the context of the split, allowing its political and economic complexities to assist in our understanding of these important matches.

The Tito-Stalin Split

Origins

Tito viewed Josef Stalin as a role model, yet his 1948 conflict was not the first time that Stalin and the CPSU had called for Tito’s ousting. Although educated in Moscow, Tito was never one to blindly follow the Soviet line. Rather, after experiencing both the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the brutal repression of Stalinism during the purges in the 1930s, Tito recognized the distinct differences between a Leninist and a Stalinist state.[11] Tito’s experience gave him the conviction to lead Yugoslavia independently, free from Soviet influence or interventions.[12] He made no secret of this, and by the end of the 1930s, Tito was in the crosshairs of Stalin’s brutal purges. Accused of Trotskyism after he strayed from Soviet instructions for the 1938 Yugoslav parliamentary elections, Tito narrowly avoided being purged in 1939, as Stalin and the Soviets were distracted by their invasion of Poland that same year.[13]

Later, when the royal government of Yugoslavia quickly surrendered to the invading Nazis in 1941, Yugoslavia was divided among the Axis powers.[14] In Tito’s summation, Yugoslavia was thus betrayed by its bourgeoisie and the only salvation for the people would be a workers’ rebellion. The Comintern in Moscow, however, discouraged him from applying revolutionary rhetoric to the struggle. Tito was told that partisan warfare was needed to liberate the state and the focus must be on fighting fascism. Regardless, Tito campaigned to label the war a struggle for “social emancipation.”[15] He was held back from this in the KPJ by growing Croatian nationalism within the Communist movement and Moscow placing him in its crosshairs and working against him again for his insubordination. While he ultimately drew down his campaign, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union was Tito’s true saving grace from being purged by Moscow in the early years of WWII.[16] The episode fostered a growing distrust between him and the Soviet leaders but again reinforced his commitment to independence.

These disagreements may make it appear that Tito was the primary antagonist in this period of Yugoslav-Soviet relations. However, as Tito, in his role as commander of the partisan National Liberation Army, saw his repeated requests for military assistance from the Soviet Union produce little,[17] the animosity he and the upper leadership of KPJ felt towards Moscow was validated and reinforced. Perhaps more importantly, Yugoslav communists saw that their eventual victory was achieved largely independently and constituted the second independently successful socialist revolution ever. While for the average Yugoslav “Stalin was the symbol of resistance to Hitler,”[18] Tito had been shown that Moscow was not to be relied upon. The Soviets only sent significant aid near the end of the war and only in amounts large enough to potentially minimize the independence of the Yugoslav partisans’ achievements.[19]

After the war, Tito began building a Yugoslav state modeled upon the Soviet Union. Although he continued to see Stalin and the USSR as role models, he remained committed to Yugoslav independence, publicly stating as early as 1945 that Yugoslavia would not “become the pawn of any policy having to do with spheres of interest” and would not “be dependent on anyone any longer.”[20] Following the example of the USSR, however, made sense as both it and Yugoslavia were multi-ethnic states that had launched successful socialist revolutions.[21] Thus, as Tito rapidly established Soviet—Stalinist—style socialism in Yugoslavia, he and the KPJ rose to claim the second position of respect among the Eastern Bloc states.[22]

Meanwhile, both Milovan Djilas and Vladimir Dedijer initially believed that Stalin viewed the Yugoslav successes as evidence that Tito would be valuable to him, due to the Yugoslav Marshal’s outward commitment to Stalinist ideals.[23] Despite this, Tito’s commitment to Yugoslav independence never wavered and much of this warming in relations came due to the special position Stalin was affording Tito as de facto second in command of the Eastern Bloc. Thus, during this period, the seeds for the split were sown.

The Build-Up

In the years leading up to 1948, it was already evident that Tito tended to trust himself and his comrades more than the Soviets. This mentality was not simple narcissism or bullheadedness; Tito had assumed that the tightening of his relationship with Stalin—made evident by Yugoslavia’s leading role in the Cominform and the warm reception of its path to communism—awarded him some leeway in pursuing his own policies.[24] Yet, Tito’s closest comrades saw through this and recognized that Stalin’s courting of Tito was not from a genuine pleasure in his governing of Yugoslavia, but rather a ploy to tighten the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe. Yugoslav Foreign Minister Milovan Djilas, whom Tito relied on in the early stages of his leadership as an adviser, felt that the establishment of the Cominform was not a concerted effort to coordinate the international socialist movement. Rather, it was precipitated when the Soviets and the Yugoslavs rejected the Marshall Plan, leading to a Soviet need for a structure to assert dominance over its satellites.[25]

Further, Tito’s belief that his relationship with Stalin was somehow special was disproven when the KPJ realized that Soviet-Yugoslav economic treaties were identical to those signed with other satellite states. Vladimir Dedijer stated that these treaties proved that “the Soviet Union wanted to acquire a monopoly over Yugoslavia, thereby depriving it of economic independence and sovereignty.”[26]

Stalin’s patience with Tito began to wane as the Yugoslav began openly pursuing his own foreign policy in the Balkans. From 1945-1948, Tito operated through proxies to control Albania, initially with support from the Cominform.[27] Stalin had wanted Yugoslavia to annex Albania.[28] However, with the outbreak of the Greek Civil War, Tito unilaterally moved Yugoslav National Army (JNA) units into Albania in January 1948 to defend the Greek communist guerrillas stationed there and to protect the region from irredentist Greek nationalists. Tito’s move to support the Greek communists was made without consulting Moscow or even Albanian leader Enver Hoxha. Tito and the KPJ were also still working on moving forward with a draft agreement for a Balkan customs union with Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Albania, with the intent to form a Balkan Federation of some sort in the future,[29] which Tito believed would strengthen Yugoslavia and the region. Although negotiations were slow-moving in early 1948, Stalin had had enough, Tito had taken this imagined leeway too far, and Stalin demanded to speak with the Yugoslavs and Bulgarians leading the Federation movement in February.

Stalin’s hope for this meeting was that Tito would be present and could be purged on the spot. Tito recognized this and sent his Vice President, Edvard Kardelj, and his Foreign Minister, Milovan Djilas, in his place. Djilas stated: “I had a premonition; I knew the Soviet leaders had no feeling for nuances and compromises, especially not within their own Communist ranks.”[30]

Stalin began the meeting by lambasting the Bulgarian leader Georgi Dimitrov for his independent foreign policy and for pursuing a federation with the Romanians when the Bulgarians had no cultural ties with them, the absence of which Stalin insisted precluded any agreement between the two.[31] Stalin turned his fury toward the Yugoslavs, also admonishing their independent foreign policy measures and confoundingly reprimanding them for not achieving a Balkan Federation with Bulgaria fast enough. He ordered that a federation between Albania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria be agreed to “tomorrow.” Both Djilas and Kardelj saw through this rhetoric, recognizing that the agreement Stalin wanted would establish satellite control over all of Eastern Europe. This became clear as Stalin planned to place the majority of the power in the federation under Dmitrov’s leadership, which he saw as more conducive to Soviet manipulation.[32]

After the Soviets left, Yugoslavia’s Djilas and Kardelj reported to the KPJ politburo that the Soviets only “sought solutions and forms for the East European countries that would solidify and secure Moscow’s domination and hegemony for a long time to come.”[33] Vladimir Dedijer later further reflected that “the Soviet government took very little account of the aspirations of our peoples. It was governed exclusively by the interests of its own foreign policy.”[34] Thus, these February meetings set the final stage for the Split, with the Soviets pressing for domination and the Yugoslavs, including Tito and the KPJ, standing for their independence.

The Split

The split can be traced through a series of letters across three months between the Central Committees of the KPJ and CPSU.[35] The first letter, sent by the Yugoslavs on March 20, 1948, addresses the Soviet withdrawal of military and civilian advisers from Yugoslavia. The Soviets stated that their advisers were “surrounded by unfriendliness, and treated with hostility.”[36] Meanwhile, the Yugoslavs felt the Soviets were attempting to undermine their regime by seeking information outside of approved channels. However, they felt that the removal of advisers was unprompted, stating: “We feel that the present course of events is harmful to both countries and that sooner or later everything that is interfering with friendly relations between our countries must be eliminated.”[37] Although respectful, the letter indicates that the Yugoslavs recognized their independence was being threatened imminently. In a meeting of the Central Committee of the KPJ, possible pressures that the Soviets would apply to force Yugoslav submission were discussed in the context of how to defend Yugoslav independence.[38]

The second letter, from the Soviets, dated 27 March, 1948, methodically refutes Yugoslav complaints made in the first letter. The Soviets claim the Yugoslavs caused the removal of the advisers as the Yugoslavs never condemned Djilas for previously publicly stating that Soviet officers were morally “inferior to the officers of the British army.”[39] Further, surveilling the advisers by Yugoslav secret police created an anti-Communist environment. The Soviets expressed anger with how the Yugoslavs couched their criticisms of Soviet policy within the language of revolutionary socialism, such as “socialism in the Soviet Union has ceased to be revolutionary.”[40] They then argued that the Yugoslav revolution was irrelevant because the Yugoslavs had failed to collectivize the countryside, stamp out all aspects of capitalism, and create a “true Communist party,” as Yugoslavia was, in fact, ruled by a coalition People’s Front.[41] These were attacks on Yugoslavia’s core values and accomplishments, the foundations of Yugoslav independence. The mutual offenses led to a steep decline in relations.

The third letter, dated 13 April, 1948, came from the Yugoslavs and opened with the famous line: “No matter how much each of us loves the land of Socialism, the USSR, he can, in no case, love his own country less, which also is developing Socialism—in this concrete case the FPRY [Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia]—for which so many thousands of its most progressive people fell.”[42] The letter goes on to make respectful and logical arguments, such as by pointing out the unbalanced burden on the Yugoslavs by the expectation to pay the advisors a wage four times that earned by a commander in the Yugoslav military.[43] The letter never wavers into subservience nor ever falters from proudly upholding Yugoslav independence.

Tito argues that the Soviets misunderstood that Yugoslavs did not believe their path to socialism was inherently better than the Soviets’ – it was simply better suited to the Yugoslav reality. As such, heightened surveillance of his party by the Soviets was more befitting a capitalist enemy than a socialist brother.[44] Tito revealed his respect for the Soviets for the path they had paved for the Yugoslavs, but that didn’t mean he could ignore the reality of his state.

In the fourth letter, sent on 4 May 1948, the Soviets accused the KPJ of “behaving in a bourgeois manner and lying.”[45] The Soviets claimed that the Yugoslavs were not able to pay the advisers properly and so resorted to abusing them verbally, rendering it impossible to ask for Soviet economic assistance. They reference Tito’s speech from 1945, in which he stated: “We demand that everyone shall be master in his own house; we do not want to pay for others; we do not want to be used as a bribe in international bargaining; we do not want to get involved in any policy of spheres of influence.”[46] The Soviets show that they understood Tito and the KPJ’s position, yet they could not approve of it, as it removed the Yugoslavs from their control and allowed them an independent path. The letter ends by calling the Yugoslavs to arbitration in front of the Cominform.[47]

The next letter was a Yugoslav missive from May 17th, declining arbitration due to the Soviets’ prejudicing other Cominform members by sending them copies of the previous letters, yet also expressing continued commitment to the Soviet cause and hope for a peaceful resolution.[48]

In the last letter, on the 22nd of May, the Soviets refute the accusation of prejudicing the Cominform, and remind the Yugoslavs that, having joined the organization, they agreed to accept constructive criticism by their socialist partners and, by avoiding the meeting, the Yugoslavs behaved in an anti-Bolshevik manner and accepted guilt.[49]

The split was finalized when the Cominform published its resolution on the expulsion of the Yugoslavs on June 28th.[50] The resolution named six primary Yugoslav offenses that largely mirror those levied in the Soviet letters. First, the KPJ had pursued foreign and domestic policies that deviated from the Marxist-Leninist line. Second, by accusing the Soviet Union of imperialist ambitions, it had adopted a Trotskyist policy. Third, the permittance of capitalist elements in the Yugoslav countryside ignored traditional Marxist-Leninist ideology. Fourth, having a coalition government rather than a single party state also went against the teachings of Marxism-Leninism. Fifth, the KPJ also did not respond to criticism in a Bolshevik manner, and that by refusing arbitration, it admitted guilt for these accusations. Sixth, and finally, the resolution claimed that the KPJ had already made decisions to remove itself from the internationalist socialist movement, and the publication of the document was simply a final decision on the matter. It concluded that unless “the healthy elements” within the KPJ could rise to oppose Tito and his leadership, Yugoslavia was no longer a welcome member of the Eastern Bloc.[51]

The Tito–Stalin Split was not the product of a sudden rupture in early 1948 over the formation of the Balkan Federation or any other singular issue. Rather, it came about due to a decade-long tension between Tito’s insistence on Yugoslav independence and Stalin’s perception of Tito’s success as a threat to Soviet control of the Eastern Bloc.

Yugoslavia After the Split

The years between 1948 and 1952, just after the split, were hard on both upper and lower levels of Yugoslav society. The split came as a shock to most, with Tito saying that it had left him feeling “as if a thunderbolt had struck [him].”[52] However, Dedijer wrote that his mother had been unfazed by the event, even expressing that it showed the positive traits of the Yugoslav people: “What a strange people we are. We are never afraid to say what we think to anyone’s face, no matter how powerful he may be…now you have done the same with Stalin.”[53]

Using foreign policy documents from both the KPJ and the United States, as well as the memoirs of prominent Yugoslavs, this section will highlight the resilience shown by both segments of the Yugoslav population during the period between the split and 1952. The elites of Yugoslav society were faced with the daunting task of reorienting both foreign and domestic policy in an emergency setting, while ordinary people were forced to deal with the consequences of these decisions.

Reorienting Policy

How foreign diplomats would react to the split was a huge concern for Yugoslavia. Tito stated, “I did not know how the West would react, but I was ready to come to grips with every danger.”[54] Saving the Yugoslav state and economy required some policy finesse from both the KPJ and their Western supporters.

US diplomats were shocked by the events. Only in March 1948, Secretary of State George Marshall referenced in a telegram to the US Embassy in Yugoslavia, that the presence of Soviet influence in the region “threaten[ed] US prestige and emphasize[d] US inability [to] exert effective influence.”[55] Yet, by June, in response to the impending split, the Chargé d’Affairs to the Yugoslav Embassy, Robert Reams, said it would be the “most significant political event here since US recognition”[56] and that he believed Tito and the KPJ would seek an expansion in Western trade to free Yugoslavia from the Soviet orbit. Further, on June 29th, the day after the split, Reams urgently pressed the Secretary of State to release a statement reinforcing the US position of defending the territorial integrity of small states.[57] Secretary Marshall ultimately urged caution, but both US and British officials were excitedly planning how to take advantage of the situation. Walter Smith, US Ambassador to the Soviet Union, first suggested the US provide aid to the Yugoslavs shortly after the resolution. He suggested sending it through British channels to take advantage of well-established Yugoslav-British relations.[58]

Domestically, Tito’s primary concerns, as always, were the independence of Yugoslavia and its territorial integrity. As such, Tito was careful not to provoke Soviet military aggression, but was also unwilling to back down. He had removed two prominent KPJ Central Committee members, Andrija Hebrang and Sreten Žujović, in April for having suggested apologizing to the Soviets to prevent the split.[59] The KPJ later made repeated accusations that these two had been Soviet informants. They were eventually imprisoned.[60]

At the 5th Congress of the KPJ in July 1948, Tito was unanimously reelected as Party leader. In his speech, he highlighted the achievements of the Yugoslav revolution, refuted the Cominform resolution, and called for unity within the party and the defense of Yugoslav independence. However, Tito also indicated a commitment from the Yugoslavs to repairing Cominform relations. He stated: “We hope that the leaders of the All-Union Communist Party [Cominform] will give us the opportunity of proving, here, on the spot, all that is incorrect in the resolution. We consider that only in this case and in this way can the truth be established.”[61]

Tito’s desire to stay closely tied to the Cominform and the Soviets began to temper in November 1948 when the Cominform published a second resolution reaffirming the expulsion. Issued on the 29th of November, Socialist Yugoslavia’s Independence Day, it was timed to apply the most psychological damage possible to Tito and the KPJ.[62] This, coupled with other international communists cutting ties with the Yugoslavs—especially the Greek guerrillas whom the Yugoslavs had supported so fervently—led Tito to accept that Yugoslav foreign policy had to be reoriented.[63]

Vice President Edvard Kardelj announced this to the Federal Assembly in December 1948: “The Second World War has practically proved that states with different social systems can cooperate even in war, to say nothing of peace.”[64] However, trade had not yet been initiated with the West, and the KPJ remained fearful of Soviet military intervention. Kardelj’s address reflects the careful position that Yugoslavia had to occupy, highlighting the intention to craft closer ties with the West and noting the aggressions faced from socialist states. He balanced this with open respect for the USSR and a commitment to repairing relations with that state.[65] Thus, the speech marked an internal shift toward a more Western, yet still neutral, Yugoslav foreign policy.

In early January 1949, the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc announced an economic blockade on Yugoslavia, demanding that Tito be ousted. In response, the US Ambassador to Yugoslavia, Cavendish W. Cannon, became an early advocate urging the United States to provide aid to help the Yugoslavs. He mentioned that the US needed to drop political demands in exchange for aid as the situation had worsened to a worrying degree.[66]

Still more important was the Yugoslav concern that Western aid would be withheld until the Yugoslavs renounced communism. The entire situation had come about because Tito refused to back down on his ideals. He certainly could not, and would not, do so now. Meanwhile, the West, especially the United States, was concerned about domestic political backlash if it provided assistance to a communist state. Ultimately, however, Ambassador Cannon argued that by providing aid to Tito, even while he reaffirmed his communist ideology, the West was providing an example for other satellite states to emulate in the future, potentially resulting in the breakup of the Soviet bloc and weakening of Soviet power.[67] Thus, by mid-1949, the Yugoslavs were able to establish direct, yet still largely covert ties to the West to withstand the economic pressures from the Eastern Bloc.

On the Western side, diplomats and governments had to also carefully orient their policy directions. US diplomats like Ambassador Cannon increasingly came to see the success of Tito as a key source of US momentum in the early years of the Cold War, yet the debates over aid to Yugoslavia never ceased in the period between 1949 and 1952.[68] At the end of 1949, Secretary of State Dean Acheson would tell Edvard Kardelj, now foreign minister, that US aid could not be expected in large amounts through 1950.[69] Acheson courted other Western powers, such as the French, to supplement meager US aid to Yugoslavia.[70] The US still feared backlash, especially if the Yugoslavs reversed course and returned to the Cominform. Meanwhile, the Yugoslavs feared US abandonment if it was decided that the situation had lost its value as an instrument of pressure on the Soviets.[71]

What type of aid to provide was also debated, especially because direct aid to Europe was seen as tied to the Marshall Plan. The Yugoslavs and the Soviets had been adamantly anti-Marshall Plan, and all the communist states in Europe rejected its aid (albeit some were forced to by Stalin). Providing direct aid to Yugoslavia could appear as backtracking for both the Yugoslavs and the Americans who had argued against them, such as George Marshall. Further, although the Marshall Plan grew into a success, congressional debate over its passage had been contentious, and few wanted to change anything within it. Thus, the US preferred to provide loans, as this would not imply Yugoslav participation in the Marshall Plan and would thus avoid the political imaging problem. The US preferred this even though the Yugoslavs’ ability to repay these loans was dubious, especially as the economy continued to struggle.[72]

Although Western aid was vital, it also heightened fears of Soviet retaliation. Following the initial aid package in 1949, the US and its Western allies were already discussing whether Yugoslavia would need military assistance as well. As early as late August 1949, British intelligence reports were relayed to American diplomats monitoring the likelihood of a Soviet invasion.[73] Although American embassy staff reports to the Secretary of State initially said that there was little likelihood of a full-scale invasion warranting US military aid, as 1950 progressed, confidence in this position began to wane.[74] By January 1951, Edvard Kardelj told US Ambassador Cannon’s replacement, George V. Allen, that the KPJ was struggling to ask openly for US military aid, for fear that the Soviets would use it as a final pretext to attack.[75] Tito had also echoed this point in a meeting with then-Senator John F. Kennedy, saying that the Yugoslavs had a “moral right to seek arms from [the] US” as the Soviets were arming Cominform states, but that the Yugoslavs needed to avoid provoking the Cominform.[76] Tito continued, saying that he would not need foreign troops: “I have plenty of men… With arms, we can do all that is necessary.”[77] Tito and Kardelj still felt in 1951 that an attack from the Cominform was possible, but unlikely, telling Ambassador Allen that if there were to be a Cominform military operation, they assumed it would be against West Germany. Yet, the Yugoslavs felt the possibility of an attack was high enough to warrant preparations, such as requesting military aid.[78] The US Joint Chiefs of Staff and General Omar Bradley would eventually both argue that military aid would be necessary.[79] By early 1952, however, National Intelligence Estimates would once again revert to an opinion that a Soviet attack was unlikely, and coordinated military assistance efforts should be conducted through less urgent joint efforts between the US, Britain, and France.[80] Although military aid was not flowing during the time period discussed in this paper, the US and its Western allies respected the Yugoslav leaders’ resilience against Soviet pressures and did explore adding military aid to bolster that resilience.

The People’s Struggle

While Tito and the KPJ struggled to navigate their new political reality, the common people of Yugoslavia were left to deal with the economic, social, and psychological effects of the split and the embargo.

The psychological impact of the split was immediate. Tito recalled that, in response to the first Cominform resolution, “there were people who cried from despair in the streets that morning.”[81] This is highly likely, as the KPJ and the state media had conditioned the Yugoslav people to look to Stalin as the icon of their state’s ideology and a major benefactor of Yugoslavia. Initially, some refused to believe that Stalin himself was behind the split.[82]

Further, many of the partisan fighters who helped secure the independence of Yugoslavia began losing faith in the KPJ as the political feud continued. As the number of veterans imprisoned for their perceived sympathies toward the Soviet Union rose, many viewed the KPJ as the force-wielding, unjust authority, rather than Stalin and the USSR.[83] Tito adopted a slow approach to changing people’s minds. Taken from its new Western associates, the KPJ applied Western psychoanalytical methods to re-educate wayward partisans and KPJ members at the Red University (re-education prison) on the island of Goli Otok.[84]

Outside of re-education, from 1948 forward, the Yugoslav press scandalized all aspects of life in Cominform states, encouraging citizens to see themselves as better off in Yugoslavia despite shock and mounting hardships. Though extremely repressive, the relatively minimal violence of the KPJ methods was enough for many to restore faith in the KPJ and lose faith in Stalin.

For Tito, this line between Stalin and socialism was important. He wrote that “We did not lose faith in socialism; rather we began to lose faith in Stalin, who had betrayed the cause of socialism.”[85] He perceived himself, while forcibly re-educating those whose sympathies remained with the USSR, as also giving freedom to those who remained loyal to socialism itself. Tito’s commitment to this idea is prominently displayed throughout Vladimir Dedijer’s memoir, which was published following his own exile from Yugoslavia.[86]

At the Fifth Congress of the KPJ, held in July 1948, Tito made it extremely clear that he recognized his people would bear the brunt of the consequences of the dispute. He recognized that the only way to survive this split was to lean upon his people, and therefore, he elected to broadcast his address to the people. By doing this, he wanted to allow the public to decide for themselves whether they were willing to weather the storm for Tito and the Party.[87] Tito stated that his commitment to Yugoslav independence was in service of “the creation of a happier life for our people.”[88] Tito would later state that he felt he had been effective: “The whole country united as one man. Feelings rose high. Men of the street were proud of their country.”[89] Yet, in signing on to this plan, no Yugoslav could have predicted the hardships to come.

Not all of this pain was caused directly by the embargo, which disrupted trade and imports. Some of the pain was caused by Yugoslav state policies as they sought to heal the rift with the Cominform. The state, for instance, maintained a rigid commitment to its first Five-Year-Plan, which had been first enacted shortly before the split with the help of Soviet advisors. By placing direct emphasis on building Yugoslavia’s industrial capacities, once Cominform cooperation and assistance were gone, this left fewer state resources to go directly to the people.

In January 1950, in an attempt to dispel complaints that Yugoslavia had not properly stamped out capitalism and private property, Tito and the KPJ enacted a rapid program of agricultural collectivization. This led to massive peasant unrest, especially in Macedonia and northern Bosnia, where the state had to violently repress the disgruntled farmers.[90]

To make matters worse, Yugoslavia was hit by drought in the summer of 1950. In the Republic of Slovenia alone, it killed almost half of the corn and potato crops. Famine was feared particularly in urban areas and, in rural areas, livestock were slaughtered wholesale for food and to conserve grain. To ensure their own survival, citizens were forced to resist the government requisition demands that were a major part of Yugoslavia’s command economy system.[91]

The US and its Western allies were fearful of the social and economic effects the catastrophe could have on the stability of the regime. The Deputy Director of Mutual Defense Assistance, John H. Ohly, predicted total failure for the regime if it were not provided sufficient aid to counter the effects of the drought. He stated, for instance, that: “The general effect of the drought…will be to…increase the growing unrest and disaffection in the peasant areas…as well as in Croatia, an area which has been particularly hostile to the regime.”[92] Further, the president of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Eugene E. Black, claimed that the Yugoslav standard of living was the lowest in Eastern Europe.[93] Thus, to maintain the strength of the Yugoslav regime, the US government used stop-gap funds—budgets allocated to bills not voted on and passed by Congress—to send initial aid in late October 1950.[94] Once Congress reconvened in December, however, the Yugoslav Emergency Relief Assistance Act of 1950 was passed and provided $37.8 million (worth nearly a half billion dollars today) in food assistance.[95]

As supplies were squeezed by the embargo and drought, inflation took off. Although the command economy promised, in theory, to hold prices at state levels, shortages encouraged the creation of black markets. [96] There, those with means to sell did so with considerable markups in an effort to feed their own families. Soon, even the wages of prominent regional bureaucrats, to say nothing of common workers, were not enough to provide even subsistence. American food aid certainly provided qualified relief, but as rations of these goods were often gone by the middle of the month, families were pushed toward paying the exorbitant sums demanded by state, gray market, and black market sellers for needed foodstuffs such as meat and flour.[97] Further, the situation did not promise a fast resolution. At his New Year’s Speech in 1951, Edvard Kardelj predicted: “Even with peace, we anticipate two or three difficult years ahead.”[98]

All of this squeezed the population and led to the average Yugoslav consuming, by 1952, only two-thirds of their pre-WWII diet.[99] CIA operatives in Yugoslavia in 1951 reported that the situation was dire and “the people feel that they have not achieved the objectives for which they fought and strived.”[100]

The Yugoslav people were not given concrete proof, just rhetoric, that the Yugoslav leaders had made the right decisions leading to these hardships. The Yugoslav government struggled through these first years to keep both its economy and public support afloat. However, two summer evenings in July 1952 would entirely change the narrative of these four years between 1948 and 1952.

Helsinki, July 1952: Football for Independence

The Olympic Games were an important space for communist states to establish legitimacy and gain international prestige. The Los Angeles Times journalist Jim Murray wrote: “Athletic supremacy was politically important to countries that called themselves, ‘Democratic Peoples’ Republic.”[101] This was not lost on either of the leaders of the Soviet Union or Yugoslavia, yet the sporting culture of the Soviet Union was built with pure politics in mind. Stalin himself did not truly enjoy sports, and further held that amateurism, central to participating in the Olympics, was an entirely bourgeois concept as a worker could not have the ability to become a world-class athlete without being compensated for his labor.[102] Thus, when Stalin gained control of the Soviet Union, the state’s support of athletics was minimized. Yet, even with this logic, Stalin recognized that the value of international sport was too great for the Soviet regime to ignore.[103] As such, after Stalin’s leadership solidified, the Soviet government reversed course and crafted a system to foster success and create world-class athletes by rewarding them through “material interestedness,” providing living accommodations and scarce commodities, in return for favorable athletic performance.[104] Yet, this publicly acknowledged system of false amateurism—the Soviets were not technically paying their athletes—was still problematic when the state’s intention to compete in the Olympic Games was floated. This was largely solved by ending references to it in the Soviet press and loudly proclaiming the athletes as amateur internationally.[105] Ultimately, the final lynchpin for competing in the Olympic Games was the Soviet’s ability to field competitive athletes.[106] This would be achieved by 1952, and the Soviets accepted the invitation to compete in Helsinki, marking their first Olympic games.[107]

The political dimension of Soviet sport is important to understanding the football matches between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. This is because the Yugoslavs and all other Eastern Bloc countries were expected to, and did, adopt a Soviet athletic model of material interestedness to varying degrees, following the end of the war, much like the rest of the Eastern Bloc.[108] With the split, the Yugoslavs also recrafted their own athletic system. Soviet advisors in sport were no longer present and the system was realigned with Yugoslav self-management principles, including placing the onus on state-supported sport clubs for providing systems of “material interestedness” rather than direct state support.

Following the split, sport became a primary mechanism by which the Yugoslav government sought to educate its youth in the more decentralized socialist self-management ideology that the KPJ promoted.[109] One aspect of this education was also patriotic, emphasizing the engrained superiority of the Yugoslav vision of socialism to that of the Soviets. Furthermore, competitive successes would be viewed as a reaffirmation of Yugoslav independence, distanced from Soviet-taught principles that assigned credit for success to the state and party and instead better distributed it to the clubs and athletes, who were given more control over their funds and management.[110] In yet another major sports policy shift, following the split, Yugoslav football lost most of its historical international opponents as all sporting contacts with the East were cut; sports administrators were forced to foster closer ties with Yugoslavia’s new Western acquaintances. These circumstances rendered the coming football matches in Finland an international spectacle, heavy with political, emotional, and symbolic significance.

July 20th and 22nd, Tampere, Finland

The Games of the XV Olympiad in Helsinki were already an exciting geopolitical event. With the Soviets competing for the first time, the media heavily covered their presence, especially the oddity of the separate athlete’s village for the Cominform states at Otaniemi[111] and the way that the Soviet Union and the United States were monopolizing the games as a site of conflict between one another.[112]

The games also offered the largest Olympic football tournament to date, with 27 nations fielding teams. A random draw advanced five teams automatically to the first round, with the twenty-two others being drawn in preliminary round fixtures. Both placed in the preliminary rounds, the Soviets drew Bulgaria, while the Yugoslavs drew India.[113] Both teams made quick work of their opponents—the Soviets winning 2-1 and the Yugoslavs defeating India 10-1. The two teams advanced to the first round and, for the first time since the split, were to face off on equal footing, with not only sporting but political implications as well. As Richard Mills described it: “For the Soviets, the match was an awkward hurdle in their pursuit of Olympic gold. For the Yugoslavs, it was a rare opportunity to make a stand.”[114] Further, if the Soviets lost to Tito’s Yugoslavia, especially as the Soviets had ideologically connected their athletes directly to the state, it would be an unbearable loss of face and authority among the satellites.[115]

Yugoslav leaders had been waiting for an opportunity like this since the split. Since 1948 the Yugoslav press had been highly critical of sport in the Eastern Bloc. Sport, one of Belgrade’s top newspapers for sporting coverage, accused the Soviets of attempting to exploit the Games for “Cominform objectives”[116] and compared the Soviets’ use of sport as propaganda rather than enjoyment to the Nazis’ behavior at the 1936 Olympic Games.[117] When it became evident that the Soviets and Yugoslavs would faceoff directly, the content of Yugoslav press criticisms intensified, claiming that the Soviets would drug players or rig domestic competition to have the national team play as the Olympic team.[118] The validity of the first criticism is debatable, yet the possibility of it being true is greater than zero. The second criticism typically relied on accusations of the Soviet team being professional and specifically that the Soviet national selection was taken from the TsDKA—the army sports club. Historian Robert Edelman has shown that only three of the starters for the national team came from TsDKA, however, with most of the Soviet side representing clubs throughout the USSR.[119] Both of these accusations were also somewhat hypocritical as both teams used material interestedness and Yugslavia’s own Partizan Belgrade army club was modeled after TsDKA. Overall, the media in Yugoslavia created such a storm surrounding the match-up that even those generally uninterested in football were tuned into the match, hoping that the country’s boys would emerge victorious.[120]

Soviet press coverage of the match-up was minimal. This was largely due to the very heavy coverage given to the much more important US-USSR rivalry in the broader games.[121] The US lost its preliminary round match, thus a US-USSR football match was never destined to transpire. Without this media frenzy, and later with the embarrassment of the Soviet’s ultimate loss, football was not a major focus for the USSR in the XV Olympiad. The Soviet players could not have felt the same groundswell of support as the Yugoslavs.

Official communications to the teams were also similarly weighted. Soviet athletes heading to the Games were informed that they were to act as diplomatic agents of the state, meaning that their actions and the results were to be watched and judged as direct representations of the Soviet Union.[122] Meanwhile, the Yugoslav team, before the first match against the Soviets, received over 400 supportive telegrams from various organizations throughout the state.[123]

In an account of the matches based on his diary, Yugoslav forward Stjepan Bobek stated that he and his teammates did not understand the true political implication of the match, yet “some primordial feeling of justice told us that our Party was in the right.”[124] While both teams likely went into the first match-up understanding that there were consequences beyond sport if they did not perform well, only the Yugoslavs could have truly felt that they had their country united specifically behind them.

The match started handsomely for the Yugoslavs, and it appeared as if their footballing victory was going to ensure that there would be no doubts about the superiority of the Yugoslav system. Going into the half, the Yugoslavs were ahead three to nil, with goals scored by national heroes Rajko Mitić, Tihomir Ognjanov, and Branko Zebec. Quickly off the restart for the second half, Mitić scored again, but the Soviets would grab one back. At the 75th minute, Stjepan Bobek would add one more, and the Yugoslavs were ahead 5 to 1 with the entire state buzzing with excitement. Yet, in these final fifteen minutes of regular time, disaster struck, and the Soviets would score four goals off corner kicks, with the final goal coming seconds before the final whistle. Thirty minutes of extra time were added to no avail, sending the teams home tied with a replay scheduled two days later.[125] Vladimir Dedijer recalled the disbelief as the Yugoslavs completed the most catastrophic lapse in defense in their footballing history, stating: “The atmosphere was one of national mourning when the Russians started scoring.”[126] Stjepan Bobek recounted that the Yugoslav goalkeeper Vladimir Beara was unable to sleep and simply wandered the streets of Tampere in the early hours of the morning. One of the team doctors, Mihailo Andrejević was near tears as he felt the politicized atmosphere had raised the emotions for all involved.[127] The political tensions of the first match undoubtedly raised emotions for both teams, but tensions for the replay were bound to be higher.

With one day of rest between the two matches, the Soviet coach Arkadiev would make the fateful decision to put his players through a long practice session, while the Yugoslavs took the day for recovery. The Yugoslav team had placed immense pressure on itself to succeed as a symbol for the state, and even if manager Aleksander Tirnanić had elected to schedule a training session, the players were too depressed to gain any value from it. For the Yugoslavs, the match was not about football, it was about independence and pride, so they put their entire soul into it—it cannot be claimed this mattered in the same way to the Soviets. Regardless, the Soviets would make one change to their starting lineup, while the Yugoslavs would send out the same eleven they had in the first match.[128]

Though there was considerable support and excitement surrounding the first match, the replay garnered a still greater flood of reporters, fans, and fellow communist athletes to the stadium. Nearly 20,000 fans came to support both squads, with the Soviets enlisting the entire Hungarian team to come and support them as they had been discomforted by the local Finnish support for the Yugoslavs in the first match. Further, the 400 telegrams sent to the Yugoslav team before the first match were multiplied exponentially as thousands more were passed along to the team, including one from Tito and the leaders of the KPJ, which was read to the team as they prepared for the match. Bobek would claim that this support pulled the team out of their deep depression, while Yugoslav winger Vujadin Boškov would tell reporters right before the match: “We are not alone, the whole of Yugoslavia is with us.”[129] The Yugoslavs conceded a goal to the Soviets in the first half, igniting fears of once again being undone by a lapse in defending; however, they went into the halftime break with a 2-1 lead. Determined not to repeat the mistakes made two days earlier, the Yugoslavs remained defensively firm through the second half. Bolstered by the genuine excitement surrounding this replay match, they went on to win 3 to 1, successfully defending their independence in the realm of football.[130]

The elation from winning this match reverberated throughout Yugoslavia. People had gathered in the central squares of the largest cities and in front of radios in the smallest villages to listen to the commentary as their team took down the Soviets. The well-known sports commentator Radivoje Marković would deliver a powerful summation: “This Olympic team of ours…delivered a heavy blow to Stalin and the Cominform.”[131] Finally, after nearly four years, the Yugoslavs had won a concrete victory over Stalin and the Soviet Union. Football may be just a game, but to the Yugoslavs, it represented much more. The Yugoslav Navy sent a telegram to the team the day after stating: “All our ships sounded their whistles to salute your victory. This triumph is a significant success for the representatives of socialist Yugoslavia. We send you best wishes.” In Sevojno, a small town near Užice, three thousand workers declared that they were so inspired by the victory that they were going to work harder to repay the footballers by finishing the construction of a copper rolling factory ahead of schedule.[132] The Yugoslav manager, Aleksander Tirnanić, a close friend of Dedijer, sent a letter stating: “Dear Vlado, This is my happiest day. After our greatest and most wonderful victory, best regards. Fondly, Tirke.”[133] This victory seemed to reward the Yugoslav people for their resilience during those long years following the split.

The consequences levied against the losing Soviet side served to cement the political importance of the games and, in fact, further bolster the Yugoslav since the victory. Newspapers in Yugoslavia would incorrectly state that the Soviet team was disbanded, and the players imprisoned in Siberia. In reality, it was not the Olympic team, but rather the TsDKA club was disbanded and not reformed until well after Stalin’s death. None of the Soviet players were imprisoned, but nor would any ever play professional football again.[134] The Soviet team’s refusal to salute the Yugoslavs after their loss and the Soviet captain’s refusal of the customary post-game captains’ handshake seemed to have indicated that they were aware of the consequences that would face them upon their return home. Dedijer would jokingly remark: “Some French papers published the fantastic news that after their defeat in Tampere, the Soviet team had been disbanded and each player sent to a small provincial town. Poor fellows—but they got off rather lightly—they could have ended up in Siberia!”[135] Though the Yugoslavs would fall to another Cominform state, Hungary, in the gold medal match, and thus take home the silver overall, the real victory of defeating the Soviets had been achieved.[136] Thus, both Yugoslavia’s political elite and common people could feel rewarded for their resilience following the split.

Conclusion

Although the two football matches in Tampere represent a minuscule moment in the wider timeline of Cold War history, they carried immense importance to the Yugoslav people. Although easily overshadowed by other high-profile events, the matches were an important emotional release and moment of unity for Yugoslavians in the aftermath of the Tito-Stalin split. While their importance can’t be said to have been the same for the Soviet public or the Soviet media, the games did produce a dramatic reaction from the Soviet leadership and for the team members, meaning that the matches carried immense value to the state elites on both sides.

These matches do provide a valuable bookend within the post-split era of Yugoslav history. In the years between 1948 and 1952 both Yugoslav elites and public were faced with troubles. Tito and the KPJ’s leadership were flung into an uncharted space in the new Cold War world, one without natural allies or guarantees. They were forced to reorient policy to maintain their national independence and keep their people fed and united. Yugoslav citizens were equally flung into a confusing space where former heroes and role models suddenly became enemies while the economy around them quite quickly crumbled. They would continue to face hardships after the gaming victories of 1952, but they were left with a concrete affirmation that their hardships were not irrelevant.

Bibliography

Unpublished Archival Sources

Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room. CIA. Web.

Published Sources

Antić, Ana. “The Pedagogy of Workers’ Self-Management: Terror, Therapy, and Reform Communism in Yugoslavia after the Tito-Stalin Split.” Journal of Social History 50, no. 1 (Fall 2013): 179-203. Web.

Bass, Robert and Elizabeth Marbury, eds. The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 1948-58: A Documentary Record. New York: Prospect Books, 1959.

Blutstein, Harry. Cold War Olympics: A New Battlefront in Psychological Warfare, 1948-1956. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2022.

Calic, Marie-Janine. A History of Yugoslavia. Translated by Dona Geyer. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 2019. Web.

Christman, Henry M., ed. The Essential Tito. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1970.

Connelly, John. From Peoples into Nations: A History of Eastern Europe. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Dedijer, Vladimir. The Battle Stalin Lost: Memoirs of Yugoslavia, 1948-1953. New York: The Viking Press, 1971.

Djilas, Milovan. Conversations with Stalin. Translated by Michael B. Petrovich. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1962.

Edelman, Robert. Serious Fun: A History of Spectator Sports in the USSR. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Kardelj, Edvard. Yugoslavia’s Foreign Policy. Belgrade: Komunistička partija Jugoslavije, 1949.

Keys, Barbara J. Globalizing Sport: National Rivalry and International Community in the 1930s. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Kolkka, Sulo, ed. The Official Report of the Organising Committee for the Games of the XV Olympiad Helsinki 1952. Translated by Alex Matson. Helsinki, Finland: The Organising Committee for the XV Olympiad Helsinki 1952, 1955. Web.

Mills, Richard. “Cold War Football: Soviet Defence and Yugoslav Attack following the Tito-Stalin Split of 1948.” Europe-Asia Studies 68, no. 10 (December 2016): 1736-1758. Web.

Mills, Richard. The Politics of Football in Yugoslavia: Sport, Nationalism and the State. London: I.B. Tauris, 2018.

Redihan, Erin. The Olympics and the Cold War, 1948-1968: Sport as Battleground in the U.S. – Soviet Rivalry. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2017.

Riordan, James. Sport in Soviet Society: Development of Sport and Physical Education in Russia and the USSR. London: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Riordan, James. “The Impact of Communism on Sport.” In The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century, edited by Jim Riordan and Arnd Krüger. London: E & FN Spon, 1999.

Senn, Alfred E. Power, Politics, and the Olympic Games. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics, 1999.

Swain, Geoffrey. Tito: A Biography. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

United States. Department of State. Foreign Relations of the United States [FRUS].

1948: Volume 4: Eastern Europe; The Soviet Union. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office [G.P.O.], 1974.

1949: Volume 5: Eastern Europe; The Soviet Union. Washington D.C.: G.P.O., 1975.

1950: Volume 4: Central and Eastern Europe: The Soviet Union, Washington D.C.: G.P.O., 1980.

1951: Volume 4.2: Europe: Political and Economic Developments, Washington D.C.: G.P.O., 1985.

Parks, Jennifer. “Verbal Gymnastics: Sports, bureaucracy, and the Soviet Union’s entrance into the Olympic Games, 1946-1952.” In East plays West: Sport and the Cold War, edited by Stephen Wagg and David L. Andrews. London: Routledge, 2007.

Wilson, Duncan. Tito’s Yugoslavia. London: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Footnotes

[1] “Resolution of the Information Bureau Concerning the Situation in the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, June 28, 1948,” in The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 1948-1958: A Documentary Record, eds. Robert Bass and Elizabeth Marbury (New York: Prospect Books, 1959), 40-46. Henceforward, this document will be referred to as “Cominform Resolution”.

[2] In Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian, Komunistička partija Jugoslavije; “Cominform Resolution,” 45.

[3] Vladimir Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost: Memoirs of Yugoslavia 1948-1953 (New York: The Viking Press, 1971), 306.

[4] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, XI.

[5] John Connelly, From Peoples into Nations: A History of Eastern Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 538; 563.

[6] Calic, A History, 176.

[7] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 77.

[8] Milovan Djilas, Conversations with Stalin (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., 1962), 132; 127. Djilas is more widely known as Yugoslavia’s greatest dissident, publishing books like New Class criticizing the Yugoslav regime, but during the period discussed in this work, Djilas is an important member of the upper echelon of the Yugoslav system.

[9] Richard Mills, The Politics of Football in Yugoslavia: Sport, Nationalism, and the State (London: I.B. Tauris, 2018), 102; Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1741.

[10] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1737. A salient US-focused example would be the U.S. hockey victory over the Soviets in Lake Placid in 1980.

[11] Swain, Tito, 20. Tito was given a position in Moscow as an agent of the Comintern whose mission was to influence the rise and establishment of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

[12] Swain, Tito, 22.

[13] Ibid., 25.

[14] Calic, A History, 125. Germany annexed Slovenia while occupying Serbia and the Banat and placing a puppet regime in power in Croatia led by Ante Pavelić. Italy occupied southern Slovenia, Dalmatia, and Montenegro, and its protectorate in Albania was given control over Kosovo and Western Macedonia. Bulgaria claimed eastern Macedonia and Hungary claimed territory on the Danube.

[15] Swain, Tito, 33.

[16] Swain, Tito, 31.

[17] Calic, A History, 177.

[18] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 43.

[19] Swain, Tito, 69; 50. Its likely that Stalin began supplying aid to the Yugoslavs in 1944 to court greater favor with Tito and the KPJ after Winston Churchill asserted that Yugoslavia rightfully belonged in his sphere of influence.

[20] Calic, A History, 177.

[21] Swain, Tito, 84; 53.

[22] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, XVIII.

[23] Djilas, Conversations, 129; Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 100.

[24] Swain, Tito, 89.

[25] Djilas, Conversations, 129.

[26] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 76-77.

[27] Swain, Tito, 86.

[28] Djilas, Conversations, 145. Djilas expresses reservations about this order as he feels that this is an attempt by Stalin to paint the Yugoslavs as an imperialist state, easing his path to direct control over it.

[29] Swain, Tito, 91.

[30] Djilas, Conversations, 139.

[31] Ibid., 174-176.

[32] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 33-34; Djilas, Conversations, 181.

[33] Ibid., 177-178.

[34] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 53.

[35] All of the letters from the Yugoslavs are signed directly by Tito or Tito and Kardelj, while the Soviet letters are signed collectively by the Central Committee,

[36] Dedijer, Tito, 329.

[37] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 5-6.

[38] Dedijer, Tito, 328.

[39] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 8.

[40] Ibid., 9.

[41] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 11. The People’s Front was not a true coalition as it was dominated by the KPJ, but this body allowed former royal ministers to remain in government in the state.

[42] Ibid., 15.

[43] Ibid., 16.

[44] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 20-22.

[45] Ibid., 24.

[46] Ibid., 25-27.

[47] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 35.

[48] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 35-36.

[49] Ibid., 37-39.

[50] It is interesting, if not important, to note that this is the anniversary of the Serb defeat by the Ottomans at Kosovo Polje in the 14th century—a battle that eliminated Medieval Serbia from the map. Thus, the date held immense nationalistic importance to the Serbs, a fact the Soviets knew. Thus, the selected date of publication may have been chosen to inflict the most pain on the Yugoslav populace.

[51] The Soviet-Yugoslav Controversy, 41-46.

[52] Dedijer, Tito, 332.

[53] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 132.

[54] Dedijer, Tito, 377.

[55] “The Secretary of State to the Embassy in Yugoslavia,” [Doc 222] in United States, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948, Eastern Europe; The Soviet Union, Volume IV (Washington D.C., G.P.O., 1974) [FRUS 1948 4], 614. Citation style for FRUS documents is borrowed from Marc Trachtenberg.

[56] FRUS 1948 4:696, 2006.

[57] FRUS 1948 4:698.

[58] FRUS 1948 4:700; 703; 717.

[59] Swain, Tito, 93-94.

[60] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 141.

[61] “Report to the Fifth Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia,” in The Essential Tito, ed. Henry M. Christman (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1970), 76.

[62] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 105.

[63] Swain, Tito, 97.

[64] Edvard Kardelj, Yugoslavia’s Foreign Policy (Belgrade: Komunistička partija Jugoslavije, 1949), 5.

[65] Kardelj, Yugoslavia’s Foreign Policy, 35; 60.

[66] “Document 522,” United States, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1949, Eastern Europe; The Soviet Union, Volume V [FRUS 1949 5] (Washington D.C., G.P.O., 1975).

[67] FRUS 1949 5:520-522.

[68] FRUS 1949 5:588.

[69] FRUS 1949 5:596

[70] “Document 762,” United States, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1950, Central and Eastern Europe; The Soviet Union, Volume V [FRUS 1950 5] (Washington D.C., G.P.O., 1980).

[71] FRUS 1950 5:781.

[72] FRUS 1950 5:827-831.

[73] FRUS 1949 5: 563.

[74] FRUS 1949 5: 564-5.

[75] FRUS 1951 4.2:371.

[76] FRUS 1951 4.2:373, 1259.

[77] FRUS 1951 4.2:373, 1260.

[78] FRUS 1951 4.2:380.

[79] FRUS 1951 4.2:376; 387.

[80] “Document 633,” United States, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954, Eastern Europe; Soviet Union; Eastern Mediterranean, Volume VIII (Washington D.C., G.P.O., 1988).

[81] Dedijer, Tito, 362-363.

[82] Ibid., 364.

[83] Ana Antić, “The Pedagogy of Workers’ Self-Management: Terror, Therapy, and Reform Communism in Yugoslavia after the Tito-Stalin Split,” Journal of Social History 50, no.1 (Fall 2013): 179-203, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43919921, 183.

[84] Antić, “Pedagogy,” 181.

[85] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 148.

[86] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost.

[87] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 145.

[88] “Report to the Fifth Congress,” 69.

[89] Dedijer, Tito, 363.

[90] Swain, Tito, 99.

[91] CIA, “Economic Situation in Yugoslavia,” October 18, 1950.

[92] FRUS 1950 5:838, 2689.

[93] FRUS 1950 5:839.

[94] FRUS 1950 5:857.

[95] “Document 361,” United States, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1951, Europe: Political and Economic Developments, Volume IV, Part 2 [FRUS 1951 4.2] (Washington D.C., G.P.O., 1980).

[96] CIA, “Living Conditions and Morale in Yugoslavia,” June 21, 1951.

[97] CIA, “Current Political and Economic Conditions in Yugoslavia,” June 25, 1951.

[98] CIA, “Comments of Edvard Kardelj,” January 9, 1951, 1.

[99] Calic, A History, 177.

[100] CIA, “Living Conditions and Morale in Yugoslavia,” June 21, 1951, 1.

[101] Quoted in Robert Edelman, Serious Fun: A History of Spectator Sports in the USSR (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), vii.

[102] Jennifer Parks, “Verbal Gymnastics: Sports, bureaucracy, and the Soviet Union’s entrance into the Olympic Games, 1946-1952,” in East plays West: Sport and the Cold War, eds. Stephen Wagg and David L. Andrews (London: Routledge, 2007), 27.

[103] Barbara J. Keys, Globalizing Sport: National Rivalry and International Community in the 1930s (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006), 160.

[104] James Riordan, Sport in Soviet Society: Development of Sport and Physical Education in Russia and the USSR (London: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 162.

[105] Parks, “Verbal Gymnastics,” 30; Edelman, Serious Fun, 6.

[106] Parks, “Verbal Gymnastics,” 32.

[107] Sulo Kolkka, ed., The Official Report of the Organising Committee for the Games of the XV Olympiad Helsinki 1952, trans. by Alex Matson (Helsinki, Finland: The Organising Committee for the XV Olympiad Helsinki 1952, 1955), 14. https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/70779/the-official-report-of-the-organising-committee-for-the-games-of-the-xv-olympiad-ed-sulo-kolkka.

[108] James Riordan, “The Impact of Communism on Sport,” in The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century, eds. Jim Riordan and Arnd Krüger (London: E & FN Spon, 1999), 50.

[109] Mills, Politics, 103.

[110] Edelman, Serious Fun, 9.

[111] Kolkka, Official Report, 88.

[112] Erin Elizabeth Redihan, The Olympics and the Cold War, 1948-1968: Sport as Battleground in the U.S.-Soviet Rivalry (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2017), 115.

[113] Kolkka, Official Report, 656.

[114] Mills, Politics, 104.

[115] Harry Blutstein, Cold War Olympics: A New Battlefront in Psychological Warfare, 1948-1956, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2022), 40.

[116] Ibid., 1743

[117] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1742.

[118] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1745.

[119] Edelman, Serious Fun, 104.

[120] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 306.

[121] Alfred E. Senn, Power, Politics, and the Olympic Games (Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics, 1999), 103.

[122] Redihan, The Olympics, 110.

[123] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1747.

[124] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1747.

[125] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 306.

[126] Ibid., 307.

[127] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1748.

[128] Edelman, Serious Fun, 105. Interesting to note that the Yugoslavs played the same eleven players in every match of the tournament.

[129] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1748-1749.

[130] Kolkka, Official Report, 659.

[131] Mills, “Cold War Football,” 1749.

[132] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 307.

[133] Ibid., 308.

[134] Edelman, Serious Fun, 105.

[135] Dedijer, The Battle Stalin Lost, 309.

[136] Kolkka, Official Report, 660.

More From Vestnik

This paper is published here as part of Vestnik. See all Vestnik papers on this site here.

Vestnik was launched by SRAS in 2004 as one of the world’s first online academic journals focused on showcasing student research. We welcome and invite papers written by undergraduates, graduates, and postgraduates. Research on any subject related to the broad geographic area outlined above is accepted. This includes but is not limited to: politics, security, economics, diplomacy, identity, culture, history, demographics, language, religion, literature, and the arts. Find out more here.