Latvia is a small country on the Baltic Sea coast. Although it has maintained a distinct language and culture for hundreds of years, it has rarely been independent. Its strategic location as a transport hub lying at the borders between multiple empires has made it a target for conquest by the Swedes, Russians, Germans, Poles, Vikings, and even crusader knights. Individual Latvians have often lived under multiple empires within their lifetimes as their homes passed from one major power to the next.

Today, Latvia is independent and a NATO member with strong security guarantees. However, it also struggles with problems related to economic growth, demographic stability, and regional security.

Latvians take pride in their strong traditions of industry and as a seafaring transport hub. Latvia’s rich history has bestowed it with glorious medieval castles and a wealth of art nouveau architecture. Above all, Latvians are an educated people with strong inclinations to preserve their state and culture.

Latvia – GeoHistory Analysis

Latvia is a mostly flat country approximately the size of the US state of West Virginia. Latvia’s many lakes, thick marshlands, 12,000 rivers and streams, and dense forests provide its only natural defenses. Although ineffective at stopping invading armies, they have provided the Latvian people with the ability to resist and isolate themselves enough that Latvia’s language and culture have survived a staggeringly long history of occupation.

A majority of Latvia’s population lives around the Daugava River in the county’s center. This includes the capital, Riga, with nearly 600,000 of Latvia’s total 1.8 million people and Daugapolis, Latvia’s second biggest city, with about 80,000 more.

The Cenas Tirelis Bog in Latvia. The country is mostly flat and heavily covered in swamp, waterways, and forests which provide its only natural defenses.

The Daugava River begins in the Russian heartland and empties into the Baltic Sea and is one of Latvia’s main trade routes. It also now provides, via hydroelectric stations, about 45% of the country’s energy. Another 38% comes from natural gas, mostly imported from Russia. Other energy production comes from locally sourced peat and wind farms.

Latvia’s agricultural heartland lies just south of the Daugava River, in the Lielupe River Basin along the Lithuanian border. Although blessed with fertile land, Latvia’s agriculture is heavily dominated by grains and lack of agricultural diversity is cited as an economic security issue.

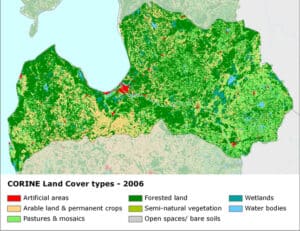

Latvia’s main natural resource is its dense woodlands, which cover about 44% of its land. The country has been known for high quality wood since the Middle Ages, as well as sought-after wood products from boats to furniture.

Latvia’s mineral wealth is limited to sand, dolomite, limestone, gypsum, clay, and peat. The country has no major metal deposits and produces no natural gas, coal, or oil of its own (although some hydrocarbon deposits have been identified). Latvia’s industries are thus dependent on imports – nearly all of which have traditionally come from Russia.

Latvia’s long sea coast offers several ports with international access. The Baltics are well connected by road and rail with direct overland connections to Poland and the rest of the EU. Latvia also has access to an LNG port in Lithuania. All of these options are more expensive than importing from Russia, but do provide opportunities for diversification.

- A map showing Latvia’s flat topography and many current water and roadways. Click for a larger image.

- Latvia land use – the red areas, marked as “artificial” are cities and towns. Click for a larger image.

Latvia’s lack of defensible borders and its long history of being occupied have made it sensitive to security issues. It joined NATO in 2004 and has actively supported Ukraine since its conflict with Russia began in 2014. Latvia has also raised its security spending from less than 1% of GDP in 2014 to nearly 2.4% in 2023. Additional raises are expected. Latvia has formed strong relationships with states with similar histories of occupation – including the other Baltic States, Poland, and Georgia.

Latvia – Early History

The first humans in Latvia arrived as glaciers receded some 12,000 years ago. As deer and other game ventured into the newly thawed areas, hunters followed.

The ancestors of the Latvians, the Balts, arrived around 2000 BC from the Black Sea area. In the Baltics, which would eventually be named for them, they found fertile agricultural land, abundant fish, and hunting and gathering opportunities in the area’s dense forests.

Those forests also created immense amounts of amber. The Amber Road developed, running along the Baltic Coast, through Central Eastern Europe to Rome. Latvia’s Daugava River, meanwhile, ran east into fur-rich Slavic lands. Thus, by the turn of the common era, Latvia was already a major trading crossroads.

Most of the travel to maintain these trade routes was performed by others. The Amber Road was maintained by Central Europeans while the Vikings dominated fur trade. Some permanent Vikings settlements were established in Latvia, including near where Riga would be founded, and fought several battles for dominance with local tribes. However, the Vikings did not make a persistent effort to rule the Balts and focused instead on maintaining rights of passage.

- A craftsman demonstrating how to make wooden spoons at the Ethnographical Open Air Museum of Latvia. Latvia’s main natural resource is its forests and its known for wooden products.

- To this day, it is easy to find small pieces of amber along Latvia’s rivers and beaches.

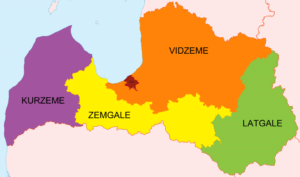

For nearly a millennium, the peoples that would become known as the Latvians remained a collection of small tribes that included the Curonians, Latgalians, Selonians, Semigallians, and others. These tribes survived through agriculture, trade, and not infrequently raiding each other. With each fiercely independent, the Baltics were one of the last areas of Europe to adopt Christianity and written language. Even today, Latvia’s historic regions are named for the major tribes that once called those regions their homeland.

Latvia’s “German Period” and Colonization as a Crusader State

Latvia’s German Period began in the mid-1100s when German merchants arrived with Catholic missionaries in tow. Although welcoming of trade, the Latvians so harshly rejected the missionaries that, in 1193, Pope Celestine III called for a crusade against the Baltic pagans.

The Teutonic Order heeded that call. A group of knights formed by Germans in Jerusalem to protect western pilgrims there, the order became a militarized arm of the Catholic Church and a tool for forcible proselytization and colonial state building.

Riga was founded in 1201 by German aristocrat Albert von Buxthoeven as a crusader stronghold. Albert also saw that an intermittent force would not be enough to conquer the land and requested that Pope Innocent III allow him to form a local, permanent military force. Thus, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword were formed in 1202.

In 1207, much of the Baltic region was declared “Terra Mariana,” or “Land of Mary” and part of the Holy Roman Empire. Albert was made a prince and given the land as his fief, although he had yet to subdue the vast majority of it. In 1215, the Pope declared that the difficult territory would be directly ruled by papal authority. Albert then became a prince-bishop. Albert’s family and many of the knights of the Livonian Brothers, most of whom were Germans, became the landed aristocracy, displacing the local elites and becoming a permanent ruling force that would last for centuries, even as Papal rule was replaced by that of other conquering empires.

King Viestards was a Semigallian who originally allied himself with the Order but never accepted Christianity. He eventually led a confederation of tribes against the crusaders. Killed in 1230, Viestards is remembered as a strong advocate for Latvian sovereignty and became a source of inspiration for later Latvian independence movements. A state award named for him is now given by Latvia for service to the country.

The Livonian Order was decimated by local tribes in the Battle of Saule in 1236 and forced to merge with the Teutonic Order in 1237 to gain reinforcements and additional funding. They kept their name and eventually built several fortresses across the region for protection. Many of these castles still stand as tourist attractions and museums today. Heavy fighting continued for most of the 13th century, with the Order eventually resorting to tactics like burning fields to starve the opposing pagans into submission.

- Riga Cathedral, historically the seat of the Archbishop of Riga, is now an Evangelical Lutheran Church.

- Medieval Livonia was a patchwork state ruled by Catholic knights and bishops.

- A statue of Albert von Buxhoeveden, the Catholic bishop credited with founding modern Riga. This statue is part of Riga Cathedral.

In 1282, Riga was admitted to the Hanseatic League, a commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds that dominated trade in northern Europe from the 13th to the 17th century. Riga exported timber, furs, and amber, and imported wine and spices. The League’s naval power helped keep the Baltic Sea safe for trade by its members. Its wealth helped bolster the crusader’s cause.

Another boost came from the collapse of the Middle East crusader states in the late 1200s. Many knights relocated to “Terra Marianna” for new opportunities to fight and gain wealth.

Even as they consolidated power, infighting rose between the ruling factions: the Livonian Order, various bishoprics, and the urban merchant guilds. These power centers spent much of the 1300s in politically complicated armed conflicts in which they sometimes allied with local tribes or received support from outside forces such as the Russians, Danes, or Swedes.

The Livonian Confederation

In 1418, Pope Martin V nominated Johannes Ambundii to the position of Archbishop of Riga and tasked him with bringing the state to order. Johannes organized the Livonian Confederation in 1435 with a diet in the centrally located town of Walk that sought to balance each power. Today, Walk is split between Latvia and Estonia.

The state was not unified. Infighting and foreign wars continued, the mounting costs of which were eventually pushed on the peasants with increased taxes and forced labor. Serfdom was established in 1494 to prevent them from fleeing an increasingly untenable situation.

When the Reformation reached Livonia in 1521, additional rifts formed between Catholic and converted Protestant knights. Lutheranism quickly overtook the cities, and, by 1525, riots had forced the Confederation to allow freedom of religion. Catholics remained strongly represented in governing structures.

At the same time, the Hanseatic League was in decline and competition for trade in Europe’s northern waters grew substantially, hurting the profits of Riga’s merchants.

The Livonian Wars and the Era of Swedish, Polish, and Russian Rivalry

While the Livonian Confederation stagnated, its neighbor, Russia, was expanding, gaining new sources of furs in the east and grain in the south. To the west, it expanded to Livonia’s borders.

Poland’s King Sigismund feared that Livonia and its export routes would be taken next. He tried to solidify his own hold on the region by forcing Livonia to become his protectorate in 1557 or face Polish troops. Weakened economically and fractured politically and socially, the Confederation had little choice but to accept.

Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia saw this as an attempt to block him completely from the Baltic Sea ports he needed to export his growing resources abroad. He invaded just months after.

Thus began the Livonian War, a complicated series of conflicts in which Poland, Lithuania, Russia, Denmark–Norway, and the Swedish Empire all fought for control of Livonia between 1558 and 1583. Ivan decimated what was left of the local troops. Livonia signed the Treaty of Villinus in 1561 with Poland to gain reinforcements; the Livonian Order was dissolved and the state became two duchies, fully secular for the first time, controlled by Poland and Lithuania.

Russia fought on and tried to create its own protectorate, the Kingdom of Livonia, through political intrigue. The last major Catholic political centers united behind Magnus, the King of Denmark’s brother, and ceded to him control of their lands. Magnus was then crowned King of Livonia by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in Moscow in 1570. For the next eight years, Livonia had two governments competing for power.

Just as it seemed Ivan’s troops would absorb Livonia, the Lithuanians and Poles merged to create the powerful Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569. The united force of both armies forced Russia’s Kingdom of Livonia to dissolve in 1578. Russia was driven back and the war ended in 1585.

Sweden’s invasion in 1600 broke that peace. However, Sweden’s victory in 1629 was followed by the most prosperous and peaceful decades that the Latvians would know to date.

- Latvia’s electoral districts are based on its cultural heritage. Vidzeme was strongly influenced by the Swedes. Latgale is the most strongly Russian. Kuzeme and Zemgale (which are often considered together) were influenced by the Poles and Lithuanians the most strongly.

- Riga’s old town skyline is often compared with that of Stockholm.

Sweden took northern Latvia and Riga. The Swedes invested heavily to expand farmland, end serfdom, launch public education, encourage publishing in Latvian, and to reduce the power of the nobility in favor of centralized, enlightened monarchical rule. To this day, Sweden and Latvia enjoy friendly relations and Latvian textbooks describe this period fondly. Latvia’s historical Vidzeme Region preserves the former Swedish borders and Riga, which lies in Vidzeme, is often compared architecturally to Stockholm.

Southern Latvia was split into duchies controlled by Poland and Lithuania. Under strong mercantilist leadership, industry, transport, and commerce rapidly expanded with arms, ships, and gunpowder all being made for export. Life for commoners remained hard, however.

About this time, the various local Baltic tribal languages finished their consolidation into modern Latvian and the stage was set for the Latvians to begin seeing themselves as a united nation.

Russian Rule

Sweden’s Baltic empire faced opposition from all sides. In 1700, a coalition of Denmark- Norway, Poland, and Russia all invaded, one after the other. Sweden defeated the first two, but eventually lost all its Baltic possessions to Russia in the Great Northern War. By 1710, Russia controlled Riga and Vidzeme.

Peter the Great undid Sweden’s reforms, restoring serfdom and the nobles’ power. However, the region retained rights to self governance, to use local languages in official capacities, and to freely practice Lutheranism.

Poland never recovered from its defeat, soon came under Russian influence, and, between 1772–1795, saw its remaining lands partitioned between its more powerful neighbors. Russia gained full control of what would become modern Latvia in the first and third partitions.

Riga lost more than half its population in the war and considerable infrastructure. It endured a 9-month siege before surrendering, coupled with a horrific outbreak of bubonic plague. Russia prioritized rebuilding the city, expanding its transport and manufacturing potential. Urbanization followed industrialization, expedited by Russia’s piloting its emancipation programs in Latvia in the early 1800s. The heavily German population was diluted by a growing Latvian proletariat.

By the mid-1800s, Riga had a large population of workers and a nearly 90% literacy rate, making it one of Russia’s best educated cities. This was thanks to the public education programs started by the Swedes and maintained by the local government. When concepts of nationalism arrived from Western Europe, they found fertile ground in Riga and the First Latvian National Awakening began. Folklore and history became popular subjects of conversation. Latvians rising in educational or economic status no longer tried to merge with the German aristocratic culture, instead seeing their own culture as independent and equal.

Alexander II tried to standardize legislation across the patchwork Russian empire starting in the 1880s. He ended the linguistic autonomy of the Baltics, forcing the government to be conducted in Russian and public schools could no longer be conducted in Latvian. The backlash against this boosted Latvia’s nascent nationalist movement further still.

According to Russia’s 1896 census, Riga was the empire’s fifth largest city at nearly a quarter million people. Local industries included metalworking, machine building, automobile manufacturing, chemical engineering, textiles, porcelain, and a range of woodworking industries. In the countryside, former serfs were increasingly educated and had purchased their homes from their aristocratic former landlords.

The 1899 European Financial Crisis quickly spread to Russia. Europe recovered by 1901, but Russia’s much weaker banking system struggled for years after. As soldiers arrived home from defeat in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, the dearth of economic opportunity led them to organize to demand change.

- A 1913 Ruso Balt automobile. Riga produced passenger cars from 1909 to 1923.

- The Monument to the Fighters of 1905 memorializes Bloody Sunday, the events that helped spark the 1905 Revolution.

In Latvia, this meant that nationalism metastasized into political movements and, when revolutionary protesters were gunned down in St. Petersburg in 1905, Riga protested in solidarity, only to be shot as well. Riga then became a major flashpoint of the 1905 Revolution. Although that revolution was eventually crushed, the city was kept under a special military regime until 1912 to contain its seething unrest.

The Tug-of-War of WWI

Germany and Russia were again at war in 1914. Russia formed the Latvian Riflemen, which quickly became celebrated units, to defend the Latvian territory. Germany prevailed anyway, largely because the riflemen’s gains were never consolidated by their Russian officers.

After the 1917 Revolution, local councils were elected, gained the support of Russia’s provisional government, and formed the national Iskolat government in 1917. However, the centrist Latvian National Council, a union of political parties, also declared itself Latvia’s legitimate government that same year and sought to create a European-style nation state. In the meantime, WWI continued to rage with the Germans gaining control.

Latvia was again divided in the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, with Riga and the south ceded to the Germans, Russia retaining the Latgale region in the east, and Vidzeme declared a zone to be “self-determined.” However, this mattered little as the German Empire collapsed shortly after.

Then, as Iskolat also collapsed and the Council gained control, the Soviets again invaded, sending in Latvian riflemen that had remained aligned with the Russian Communists.

The Red Army took back nearly all of Latvia before a counteroffensive by the Council, backed by the Germans, Poles, Estonians, Brits, and the French pushed the Soviets all the way back and even took Latgale. When the new independent Latvian state was declared in the Latvian–Soviet Peace Treaty of 1920, it included all traditionally Lativan lands.

The Complicated Birth of the First Latvian State

The population of Latvia, after such a complicated history, was demographically and politically complex. There were substantial minorities of Germans, Poles, Jews, and Russians. Latvia was mostly Lutheran, yet had many Catholics. More than 50 parties participated in the first parliamentary elections, with many small parties seeking to represent individual minorities.

Politics were further complicated by the fact that the Social Democrats dominated early elections, taking up to a third of parliamentary seats, but also generally refusing to participate in coalition governments. The work of governing fell to the second-place center-right Farmer’s Union, led by the pragmatic Karlis Ulmanis.

Latvia’s fractured political field meant that its governments were unstable and unwieldy. However, Ulmanis did well at achieving Latvia’s policy imperatives. New markets were opened abroad and industry was reopened. Land reform forcibly redistributed noble holdings to farmers, boosting agricultural development and investment. Latvia resolved border disputes with its neighbors and rebuilt its defenses. It joined the League of Nations in 1922. It also bolstered its population, which had fallen by about a third during WWI, by passing a citizenship law that allowed many farmers from Russia to flee the revolution and relocate to Latvia.

With the Great Depression in 1930, there was much more to do. Ulmanis streamlined politics by declaring a state of emergency in 1934. With the military’s support, he permanently dissolved parliament and banned all political parties, including his own. He vertically integrated the political and economic systems through state-sponsored councils and trade unions.

His regime was effective at reforming the financial system, attracting foreign investment, and reviving exports, through expanded agricultural production. By 1938, Latvia’s economy had returned to pre-Depression levels.

The Reoccupation of Latvia

Ulmanis couldn’t stop great power geopolitics. He proclaimed Latvian neutrality in 1939 and signed a nonaggression pact with the Nazis. However, that same year, The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was signed, and the Nazis ceded any claims to the Baltics to the Soviets.

The USSR then forced Ulmanis to sign the Soviet–Latvian Mutual Assistance Treaty, which made Latvia again a protectorate. Soviet troops were moved in for “protection,” but then used to forcibly change the government and absorb Latvia into the USSR in 1940. Tens of thousands of Latvians were deported into Siberia to quell resistance. Members of the former government were arrested and high taxes and production quotas were implemented to try to force collectivization. Soviet workers and bureaucrats were imported in large numbers with the intention of learning from Latvian industries and expanding them.

- The entrance of the Riga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum in Riga’s city center.

- The farm where Karlis Ulmanis was born is now an open air museum dedicated to showcasing the agricultural reforms he implemented during his rule.

In under a year, the USSR and the Nazis were at war and the Nazis held Latvia from 1941-1944. All Jews in Riga, Liepāja, and Daugavpils were confined to ghettos before being systematically murdered in 1943. At the time, Riga alone had 30,000 Jews.

The Nazis built the Kaiserwald Concentration Camp outside Riga as a regional forced labor camp for Jews deported from other Baltic and Eastern European cities. In all, the Holocaust took 85,000 lives in Latvia.

Latvians were split between those that welcomed the Nazis as an alternative to the Soviets, and those that resisted, focused on returning to either independence or Soviet rule.

Eventually, a Soviet counteroffensive pushed the Nazis all the way back to Berlin, leaving Latvia again under Soviet occupation. By the end of WWII, Latvia had lost nearly 30% of its people, 75% of its industry, and 40% of its agricultural capacity.

Soviet Latvia

The Soviet policies of 1941 were reinstated. When these proved ineffective, mass deportations were carried out in 1949. Property from those deported was confiscated and collectivized.

Resistance to communist rule remained strong with bands of partisans living and fighting in the dense forests and swamplands well into the 1950s. These bands also sought to preserve Latvian literature and neo-pagan practices that had been revived with the Latvian National Awakening but were repressed by the Soviets.

Even within the Latvian Communist Party, resistance remained to many Soviet policies until the end of the 1950s. Latvia’s “national communists” sought more economic, linguistic, and cultural autonomy. They were purged and relocated mostly to posts inside Russia.

Latvia did not experience a post-WWII baby boom. Natural population growth for ethnic Latvians remained below one percent for many years, showing they did not see the war’s end as the beginning of a hopeful new era. As the Soviets sought to revive and expand industry and transportation in Latvia, they had to do so with workers imported from elsewhere in the USSR. This also served to dilute the Latvian population and Latvian nationalism.

In 1985, glatnost was announced and Latvians began asserting themselves anew, at first with environmental protests against new hydroelectric stations and heavy industry. Politicians again asked for economic autonomy to develop light industry and consumer goods. When the USSR invaded in the 1940s, Latvia had an economy on par with Europe’s. Many older Latvians still remembered shops full of goods and questioned why that couldn’t be achieved again.

By 1988, protests escalated with demands to recognize past victims of oppression. Moscow’s response oscillated between encouraging discussion and violently dispersing gatherings, which only further galvanized the movement that would become known as the Singing Revolution. Political organizations like the Latvian National Independence Movement and the Latvian People’s Front were founded to demand change.

In August, 1989, a massive demonstration known as The Baltic Way was held. Two million people joined hands forming a human chain that stretched from northern Estonia to southern Latvia in a show of dedication to solidarity and freedom.

The 1990 Soviet elections were the first to allow multiple parties. Latvia’s Communists lost badly and the new, local political organizations formed a ruling bloc. They soon declared that Latvia would make an orderly secession from the USSR.

- Riga’s barricades were made of whatever was on hand, from trucks to concrete blocks and timber.

- US Ambassador John Carwile visits Riga’s monument to the barricades.

- Part of the Baltic Way protest that saw people join hands from Estonia to Latvia

The Soviets responded with shows of power, driving military equipment through Riga and actively prosecuting anti-Soviet sentiment. Rumors spread that Gorbachev would soon rule by decree and prevent Latvia and other republics from seceding.

In January 1991, Latvians erected ramshackle barricades around politically important buildings and staffed them largely with unarmed civilians. Soviet troops responded with gunfire, taking the lives of many Latvians.

A truce was called several days later, but many barricades were left in place as Latvians watched Moscow warily. The August, 1991 coup attempt, which would have implemented military control with the goal of restoring and preserving the USSR, proved a last straw. Latvia’s government declared full and complete independence on August 21, 1991.

Modern Latvia

Latvia’s newly independent government was unified in it vision of a freemarket, westward-facing Latvia. Within a year, new monetary reforms brought inflation, which had skyrocketed under perestroika, under control. A new privatization law allowed for the sale of state-owned assets to private individuals and companies. Also within a year, Latvia joined the UN, the International Monetary Fund, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Latvia’s new citizenship laws granted status only to those who had arrived in Latvia before 1940 or their descendants. This excluded Soviet immigrants and their families who were more likely to support communist or socialist political parties.

To this day, only about two thirds of Russian speakers in Latvia hold Latvian citizenship. The number of Russian speakers has also generally declined from about a third to a fourth of the population, with most of the loss coming from those who never received citizenship.

In 1993, Latvia adopted a new constitution that established a parliamentary government. The first independent elections were held shortly after, and a coalition government was formed that continued economic liberalization. However, Latvia struggled throughout the 1990s to transition from a command economy and to decouple itself from economic dependence on other former Soviet republics and, in particular, Russia.

In 1999, Latvia ascended to the World Trade Organization. In 2003, 67% of Latvian voters approved a referendum for EU membership. In 2004, membership was secured in both the EU and NATO.

Privatization was largely completed by the early 2000s. However, it was criticized as often opaque and that some property the state sold should have simply been restored to the families from whom the Soviets had nationalized it. The transfer of churches was also problematic as some that had been formerly held by Lutherans or the Orthodox were given to Catholics or other denominations as the state sought to satisfy the needs of all faiths.

From 2000-2007, Latvia’s GDP grew faster than any other European country, driven by a boom in construction and real estate as the economy stabilized and security guarantees improved. However, in 2008, a global financial crisis occurred centered on a collapse in real estate prices. Latvia’s economy contracted more sharply than any other European country that year, with unemployment rising to record levels.

This started Latvia’s current demographic crisis. Young, well-educated Latvians used their new ability to move and work anywhere within the EU to search for better opportunities outside Latvia. The dwindling labor force slowed recovery and only in 2021 did GDP again reach 2008 levels. The demographic crisis continues to affect all economic sectors from finance and tech to even agriculture, where an aging farming population is now considered one of Latvia’s main food security risks.

Politically, ballots in modern Latvia are often filled with alliances of smaller parties that run together but remain independent. Parties based on ideology or regional or ethnic interests all compete in this diverse and fractured field.

Most issues of concern to today’s Latvian voters are long-standing. The economy and demographics are top concerns. Corruption has been a pressing problem since Soviet times, despite international assistance and pressure. Also, reforming Latvia’s long-valued educational system and boosting teacher pay have been unfulfilled goals since independence.

- The Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater specializes in Russian language drama.

- Riga’s Central Market has been in operation since the 1920s and is still a popular destination for tourists and locals.

Latvia’s current top issue only arose in 2022, however. In the midst of parliamentary elections, Russia began what it calls its “special military operation”* in Ukraine and Latvian politics was upended. Harmony, Social Democratic and largely Russophone party, floundered, moving from holding the incumbent lead to losing all of its seats. Right and center-right parties pledged to oppose Russia and surged. They now lead the government.

Changes to policy have been mostly cultural rather than economic. Schools are moving faster to do away with Russian-language instruction in favor of Latvian-only. Also, many Russian-language TV channels have been taken off the air and websites blocked. However, about a quarter of Latvia’s population is still predominantly Russian-speaking and Russian can be heard commonly on streets of Latvia’s two largest cities: Riga and Daugavpils. Many Russian-speaking Latvians have protested these moves.

Having lived for centuries under foreign domination and at the whims of geopolitical tides, Latvians place high value on national security. History has also left Latvia with a country diverse in its religious, ethnic, and political affiliations. As a country that has also long valued education, industry, and European values, it has the resources to seek innovative ways to maintain both its security and its democracy.

You Might Also Like

Estonia: From Colonized Land to Independent E-State

Estonia is a mostly flat, small country, two thirds of which is covered by forests and marshlands. Its strategic location on the northern Baltic coast…

Kyrgyzstan: Nomadic Heritage, Modern Ambitions

Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked and highly mountainous country in Central Asia. Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan has faced a complex…

Poland: A Developing Central European Power

Poland joined the European Union in 2004 as part of the EU’s “big bang” of Eastern expansion. This broke the Cold War’s East-West divide and…

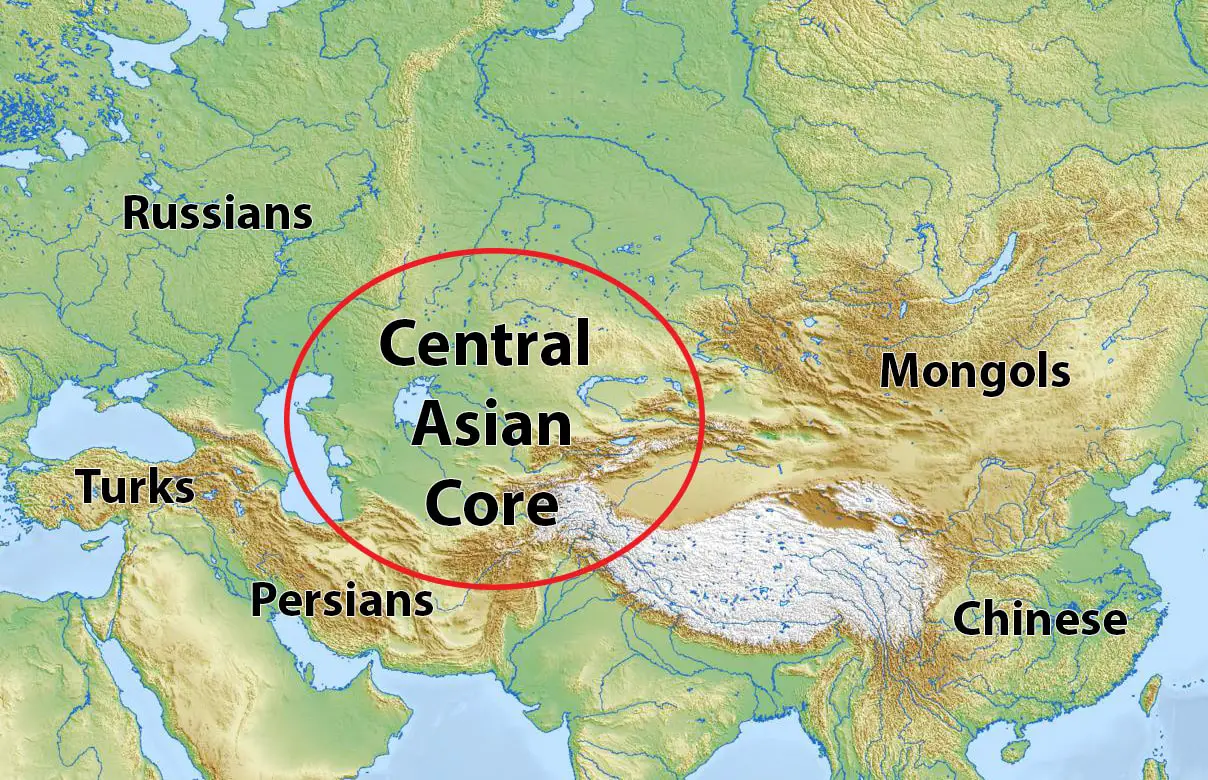

Central Asia: Core and Periphery

Central Asia is, by its most common definition, those five “stans” that were formerly Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. However, this has…

10 Obscure Videos of Soviet Moscow from the British Pathé Archive

The organization British Pathé, a creator of newsreels of historical events, digitized their archive of 82,000 documentary videos and released it on YouTube. The 3,500…