In June 2022, the governments of China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan announced that construction on the long-awaited Silk Road Railway will begin in early 2023. A project more than thirty years in the making, the railway would create thousands of jobs and provide a vital link between China and Central Asia. But many people, experts and members of the general public alike, remain skeptical that the new line will ever break ground. So, what is the Silk Road Railway project, and will it ever happen?

A Brief History

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Central Asian countries inherited a rail network that was almost entirely oriented towards Moscow. As a result, the newly independent nations were disconnected not only from each other but also from other parts of their own countries. Since the independence era, only Kazakhstan has been able to invest seriously in improving rail connectivity by expanding or updating Soviet rail lines. Thus, to the severe detriment of inter-regional connectivity, other Central Asian nations have been left with underused and drastically ineffective transit networks.

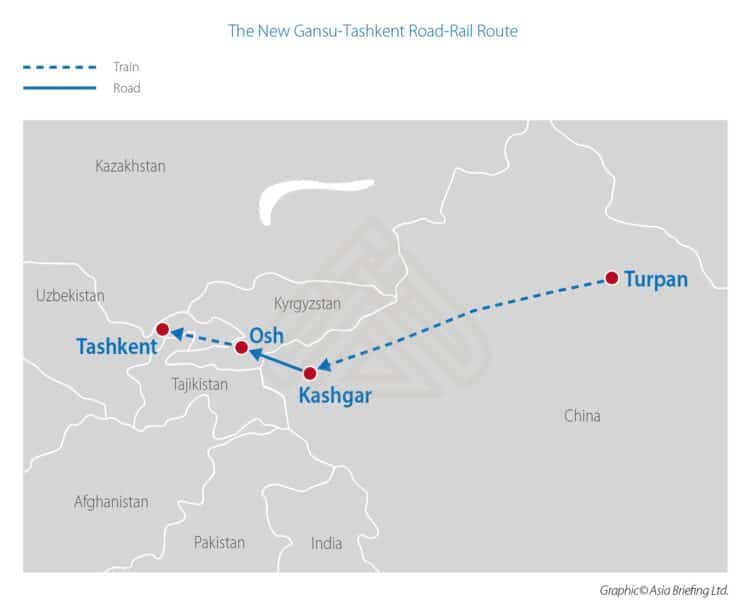

One of the earliest proposed solutions to Central Asia’s interconnectivity problems was a new railway connecting China to Uzbekistan via Kyrgyzstan. In 1998, engineering firm Gibb conducted a feasibility study and suggested that the new line should start in Kashgar (China), cross the Chinese border at Irkeshtam, and then head north to Osh (Kyrgyzstan) before terminating in Andizhan (Uzbekistan). The idea was well received by the public, but ultimately neither Kyrgyzstan nor Uzbekistan could afford such a large-scale investment at that time.

- The original route, connecting two existing lines broken only by a relatively short distance between Kangar, China, and Osh, Kyrgyzstan is the shortest connection to make. The route is currently already in use, with the current gap filled by truck freight services. However, questions of what gauge to use and if to duplicate track between Tashkent and Osh is still debated.

The project was given a new lease of life in 2013 when China unveiled its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Consisting of both land and maritime components, the BRI is perhaps one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects ever conceived. Near the top of the BRI’s list of priorities was improving rail connections between China and Central Asia, with the Silk Road Railway project primed to lead the way. But thirty years since the project was originally proposed, not a single mile of track has been laid. What, then, has prevented its construction, and why is this project so fraught with problems?

Issues with the Project

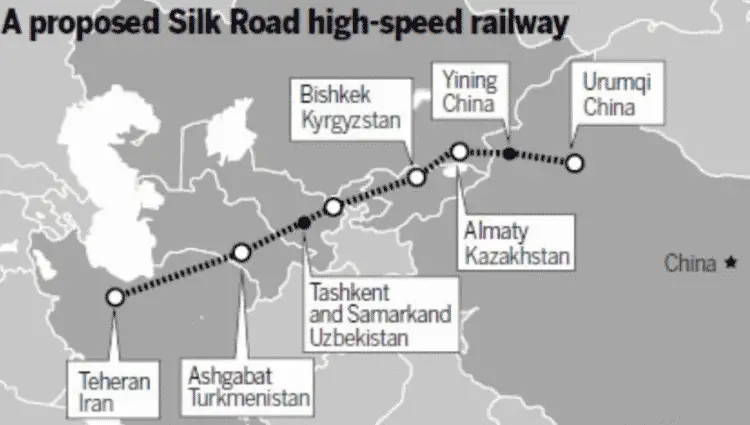

From the get-go, the project has been marred in debate and controversy. Arguably the most significant issue is the route the new line will take. The Kyrgyz government is reluctant to let any new rail line bypass its capital city Bishkek. They argue that building the railway in the north, although longer and more expensive, would allow for an easier flow of resources during construction and better serve deprived communities along the line. But understandably both China and Uzbekistan strongly favor the quicker, more direct route through Osh. Thus, until now, the Kyrgyz government has been quick to block any plan that does not involve Bishkek, much to the chagrin of the other two nations.

Another impasse has been the concern felt by both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan for the absence of guaranteed economic benefit. The railway will undoubtedly create thousands of jobs during its construction phase and infinitely improve inter-region connectivity once completed. However, the longer-term benefits are less clear. A 2012 feasibility study concluded that the railway would bring an additional $200 million annually to Kyrgzstan’s economy, but many experts believe this figure to be a gross over-estimation. The main contention is whether the imported products will have a direct impact on the Kyrgyz economy or merely represent a source of customs duties based on Kyrgyzstan being a transit country.

The financial security of the project’s long-term profitability could also be jeopardized by continued tensions across the Kyrgyz Uzbek border. In spite of a 2018 border agreement, armed conflict does still occasionally break out along the frontier, calling into question the security situation that such an infrastructure project would rely upon. As such, the true economic benefits of a rail project across the territory are unknown and investment risks are raised for all involved.

- Kyrgyzstan wants a more northerly route that would link northern Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan with Uzbekistan. Later extensions of the project would run through Iran.

Yet another issue is what gauge the new tracks should use. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan want to use an old-style (Soviet) broad gauge so that the line can seamlessly connect to their existing rail networks. This, in turn, would allow for the potential expansion of old Soviet rail lines and thus even greater connectivity. China, on the other hand, wishes to use a standard international gauge which would allow the railway to connect to its own existing high-speed rail systems. The use of a standard gauge could also promote further growth in the future, with Tehran, Iran lined up for further expansion. Using a different gauge would mean that that trains would have to regauge before entering Kyrgyzstan and again before entering Iran, leading to additional expense in time and resources for those using the line.

China’s Role in Central Asia

As well as the project-specific issues, there is a broader concern that lingers over the plans: Central Asia’s increasing distrust of China. In Uzbekistan, for example, the number of people who hold an “unfavorable” opinion towards China has increased from 27% in 2017 to 55% in 2021.[3] Similar trends can be found across Central Asia, with Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan both reporting >50% disapproval ratings for China.

Mounting debts owed by Central Asian nations to China has led some political circles to sound the alarm about protecting sovereignty from foreign ties and obligations. In order to finance their portion of the railway, for instance, the Kyrgyz government would almost certainly have to rely on Chinese loans. However, Kyrgyzstan’s national debt currently amounts to roughly $5.2 billion (~68% of GDP), more than 35% of which is already owed to China. The Kyrgyz government, then, are fearful of falling into a ‘debt-trap’ where the country becomes overly reliant on Chinese loans. Failure to repay these loans could reap severe economic, political, and even sovereign consequences, as has recently been the case in Sri Lanka.

China has also lost reputation for its inability to see projects through to their completion. Even since the BRI was announced, China has made a habit of loudly announcing grand projects and then quietly cancelling or indefinitely postponing them. For instance, in 2006 China and Turkmenistan agreed to the construction of four new gas pipelines that would supply Chinese consumers with natural gas. Three of these lines were completed by 2015, but the fourth line, which was set to be the capstone of the project, was “postponed.” Seven years later, its status remains unchanged. There is, then, a lot of speculation about China’s long-term interest in and commitment to Central Asia, a factor that has undoubtedly bolstered anti-China sentiment.

- Kyrgyzstan’s current rail system provides relatively poor rail connection between Bishkek and other capitals and poor connection within Kyrgyzstan itself. Note: this map does not include a new section of track connecting Andijan in Uzbekistan’s Fergana Valley directly with Tashkent without crossing into Tajikistan first.

In Kyrgyzstan specifically, a major 280 million dollar logistics hub was cancelled in 2020 after protests by local Kyrgyz. The protestors were apparently concerned about land being leased to a Kyrgyz-Chinese company for 49 years (with sovereignty issues apparently at the center of this). Protestors also voiced concerns about environmental and labor guarantees. In the face of the protests, China pulled the plug on the project. Other, smaller projects have seen similar fates.

The Proposed Silk Road Railway Today

According to government officials of the three countries, work will begin on the Railway in 2023. In part, this new lease of life stems from Uzbekistan’s desire to open up its economy post-pandemic and a renewed push to open a North-South corridor through Central Asia that can connect Russia, China, and India. In the shorter term, Uzbekistan sees potential to use the railway as a route for trade with Pakistan, avoiding the security concerns with transiting goods through Afghanistan.

However, it is unclear exactly what compromises have been made to get to this point. With most of the enthusiasm coming from Uzbekistan, it seems likely that the track will take the shorter, more direct route through Osh, cutting out Bishkek. There has also been no word on what gauge the line will use, how it will navigate the disputed borders, or how the project will be funded. This lack of detail has left many just as skeptical as before, and seemingly few in Central Asia genuinely believe the project will go ahead next year.

Conclusion

Central Asia, as disconnected as it is, desperately needs rail links to bring the region together. The Silk Road Railway has huge potential to transport people and generate much-needed revenue for Central Asian countries. But there appears to be no easy fixes to the towering problems that have plagued this project since its inception. That is not to say the railway will never happen; however, if we are to see a China-Uzbekistan rail line anytime soon, then all the parties involved have a monumental diplomatic task ahead of them.