“Relax every muscle right now, or you’ll break some bones!” The voice inmy head bounced through my body as I started sliding down the two flights of steps leading to an underground tunnel meant to offer safe passage across the busiest street in Novosibirsk. My fall had happened too fast to stop. Walking quickly homeward, trying to beat the Siberian cold before it could penetrate my reverse sheep skin coat, dog hair knit gloves and fur hat, I had forgotten that only half the width of those steps was habitually shoveled. The rest was like a giant slide of ice and tight-packed snow built up for the four or five months when temperatures in that part of Russia do not warm up enough to melt the frozen ground cover. My cane slipped first, and instantly after, my feet in their knee-high boots shot out from under me.

I cannot remember how long it took to hit the bottom, where the sidewalk and its metal water grate were relatively free from winter precipitation. I was too breathless to stand, gingerly checking out my still shaking body and limbs and, thank goodness, feeling no pain. Surely someone would stop to ask me if I was hurt and offer me a hand, a hand which I could really use right now, given my heavy market bag. But no one did stop. I heard them clomping by, and I wondered, were they ignoring me, or were they just too intent on beating the cold to notice or to want to help? Suddenly a little girl protested shrilly “But Mama, why can’t I? Look that lady just did it!” I began to laugh so hard at the child’s desire to mimic my great slide that it took me an additional minute or two to get up. The laugh gave me just the jolt I needed to go on.

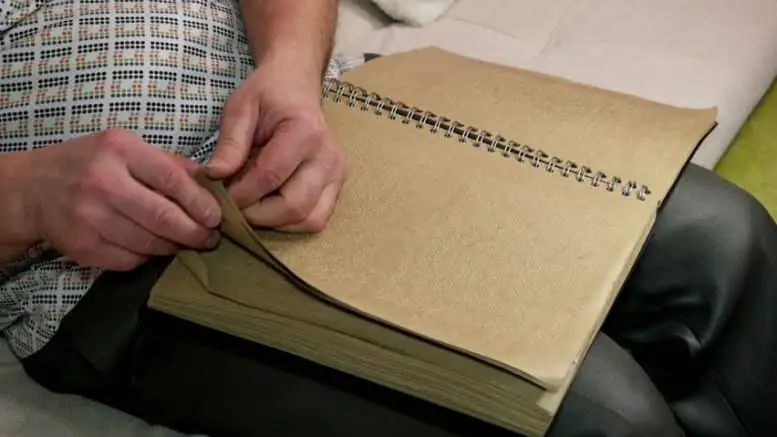

Entrance a “perekhod” underground walkway, common in Russian cities. Note the steepness of the wheelchair ramp.

Being blind in Siberia is like that – a mix of the daunting and the droll, the frightening and the fantastic. I went to Russia in 1990 as the first disabled guide on a government-sponsored citizens exchange exhibit that had begun over thirty years earlier. Moved by the kindness amidst hardship that surrounded me and convinced that I could contribute more to Russian life than to American society, I determined to stay on, and I lived in Russia and Central Asia for most of the next decade. I found tremendous support in my goals of journalism and teaching, free as employers were from fears of law suits or crazy insurance rates if they hired me. In interviews I sensed the respect of people who saw me first as a bilingual, hardy traveler interested in their life, my blindness being marginal compared to what I could contribute to their schools or businesses.

In 1994 I began working on an international disability project to unite wheelchair manufacturers and users on designing chairs adapted to the rigors of local conditions. I tried to promote barrier free design and medical education alongside my mobility impaired colleagues, many of whom had not been able to visit a doctor in years because of accessibility issues, and some of whom were house bound for months when winter came. Using my own experiences of growing up blind, I tried to address not just the problems at hand, but larger societal issues of discrimination. But my views of “Disabled of the world, unite!” struck an iron curtain when it came to making people of a given disability aware that those of any physical challenge have far more in common than what separates them, especially in how society views them. Wheelchair riders were obsessed with curbs, steps and lacking medical treatment; deaf people worried about whether their special factories for manufacturing industrial products would close, and as for the blind community, well, it was far more interested in obtaining prestigious, cutting-edge computer technology or finding sponsorship for chess clubs than in freeing young people by teaching good mobility techniques or training teachers willing to address special learning needs.

After much thought and discussion, I came up with a plan. The Novosibirsk Special Library for the Blind and Visually Impaired was located just a block away from the gym where the wheelchair club commonly convened. Thanks to finding a philosophical soul mate in the library director, and some patient architects and sponsors, we were able to make a joint agreement to widen doors and bathrooms in the library for wheelchair riders’ use for meetings and social activities.

A metro station in Novosibirsk – note the lack of wheelchair access. Wheelchair riders would have to balance on a single step, a feat of strength not many would be capable of. Moscow’s are similar.

When visually impaired library users and those in wheelchairs began brushing sleeves, they started discussing their day-to-day lives, only to discover that commonly-held Russian beliefs that their disabilities would bar them from gainful employment or from safe travel had created job and social barriers far beyond their real limitations. Those were heady days for me participating in what was by all accounts the first ever cross-disability dialogue organized in Siberia.

Meanwhile, the media, which in Communist times had alluded to disabled people as embarrassing social factors or at best, as unfortunate byproducts of bad parents, began to pay attention to us. Reporters, while initially skeptical, almost universally ended up portraying people facing physical difficulties successfully as a contrast to others in the society, who loved to complain about how bad their lives had become minus the security net that a Socialist government had provided them until only a few years earlier.

Such a thaw in attitudes was encouraging to me, but I had to learn some tricks to survive intact in Siberia that might surprise many Americans. These included the following:

-

Never start to cross a street, even when you are sure you have the light, until you have counted to 5 slowly. Drivers in Russia press a yellow light until it is most definitely red, and they don’t stop for a pedestrian, cane or no cane.

-

In the winter, run your cane all over a crossing corner, because ploughs commonly pile snow in mounds from three to five feet high right where you want to traverse the street. You may have to walk several feet or yards down the street, and even then, be ready to surmount a thigh-high pile of snow.

-

You can count on people being honest when they give you change, or at least, it was so during my decade living in Russia. When once I gave a marketer a 50 thousand ruble note instead of a 500 ruble note, he simply said, with more sadness than derision, “It just isn’t worth my cheating you on such a small thing.” It was his commentary about inflation and its affects, that the money he might dishonestly gain from me would lose much of its value in a matter of weeks.

-

Never ever stand alone with your white cane waiting except at a bus stop where others wait. People will think you are begging, and you will have coins or even an occasional bill thrust into your hand, or even your pocket. However poor many Russians are, they have much compassion for those whom they perceive as less fortunate than themselves. Instead, stand straight, fold your cane as you wait and act as though you know exactly what you’re doing.

Entrance to the “Old House” Theater. Note the packed snow on the stairs, sidewalk, and wheelchair ramp.

When I began to walk steadily homeward again, the wind bit my face as I ascended the steps across the underpassage. I could smell freshly baked bread along with the hand rolled cigarette odor prevalent during the early 1990s before Marlboro got a corner on the market. Suddenly I felt an arm reaching around me from the right, and into my market bag hand were thrust two fat, soft, still warm rolls wrapped in newspaper. “I see you walking this way every day, young woman, and I want you to enjoy these,” a woman said. I began to protest, but she was gone. There I stood, recipient of this random act of kindness. Warming myself over a cup of tea along with those rolls a few minutes later in my kitchen, I mused about that day’s events, which had shown me some of the worst and the best in humanity.

See Also:

List of Organizations in Moscow for the Blind(in Russian)

Perspektiva, an umbrella organization for the disabled in the FSU

Scholarships for NGO Internships in Russia

The author of this analysis, Elizabeth Sammons, was diagnosed as blind from a congenital eye condition when she was six weeks old.

Discovering that Elizabeth’s congenital eye condition rendered her completely blind, a doctor told her parents to institutionalize her when she was six weeks old; she would be retarded and ineducable, after all. Her parents ignored this advice, believing in the ability of mind and spirit to approach life with meaning and wonder. By fifth grade, before mainstreaming laws were in place, Elizabeth had entered a normal school classroom after several years in blind and visually impaired classes.

Elizabeth took three years to double major with honors as an undergraduate in French and Communications. Then she earned an M.A. in journalism at The Ohio State University. Meanwhile, she had developed her international interests by spending an exchange year in Switzerland, and immediately after the end of her education, by being the first disabled guide in the U.S. Information Agency’s thirty-year ongoing citizens exchange exhibit to the then Soviet Union. She continued for the next decade as a Peace Corps volunteer teaching English in Hungary, a nonprofit manager of a news advocacy group in Central Asia, and a teacher, interpreter, marketer and cross-disability advocate in Novosibirsk, Siberia. In 2000 she returned to the USA and worked as a claims representative for Social Security until her interest in doing more encouraged management to promote her into public affairs. In 2005 Elizabeth began her current job as Legislative Liaison for the Ohio Rehabilitation Services Commission.

Elizabeth currently serves in her fourth year on the Ohio Governor’s Council on People with Disabilities. As needed, she volunteers her language and teaching skills at the Columbus Russian Center, contributes occasional articles to a variety of publications and speaks for the Columbus Council on World Affairs on issues related to Russia and Eastern Europe. She speaks fluent French and Russian and is conversational in several other languages including Hungarian, German and Italian. She is on her Lutheran church’s German-American Friendship committee, leads the church book club, and is active in a number of other groups there.

Elizabeth is peacefully married and has one daughter, Sophia, age ten. She still lets her sense of wonder guide her to some tiny beauty along the path every day, making the difference between the ordinary and the miraculous.

The pictures provided focus on accessibility issues in Russia – while the picture are of locations in Novosibirsk, they could have been taken in nearly any Russian city.