As the Russian government continues to stabilize after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has become more hostile toward transnational non-governmental organizations (NGOs). New regulations on NGOs are, the Russian government argues, justified as an attempt to protect the newfound sovereignty of the Russian state. The Foreign Agent Law, which has limited the rights of NGOs and caused some to be shut down, is at the center of the NGO debate. It was written with the perception that many NGOs act with a foreign agenda or in the interests of a foreign government. Despite these challenges, however, NGOs still can be successful in Russia.

Using information collected from sources such as works by Andrey Makarychev, a prominent EU-Russia scholar currently teaching at the University of Tartu, and primary sources from the Center for NGO Development, a Russian NGO, this paper will show how some NGOs continue to maintain successful programs despite regulations and misconceptions. Only one NGO has in fact applied for and been registered as a “foreign agent” (Only). However, many of Russia’s NGOs have international partnerships, with such entities as the European Union, the Council of Europe, and other fellow members of global civil society. These successful partnerships show how the international community can still support and aid Russian NGOs.

I. What NGOs Are

NGOs are transnational actors in global and local civil societies who work with social issues. Global civil society consists of actors outside of governments, generally focusing on social problems. Rapidly, global civil society is becoming, “… not a single world state, but a system in which states are increasingly hemmed in by a set of agreements, treaties and rules of a transnational character” (Kaldor 590). To change norms, NGOs can intervene in domestic affairs, sometimes causing domestic tension (Keck and Sikkick 98). They can use accountability politics, “name and shame the actor,” exposing an actor’s inconsistencies to the public (Keck and Sikkick 95). NGOs operate using a “boomerang effect,” where “domestic political actors in one country, finding their own government resistant to their agenda, ally with foreign or international NGOs, which in turn mobilize their governments or intergovernmental authorities to put pressure on the offending government” (Nelson 118).

NGOs carry power because most states will respond to their challenges. Whether the state’s response is positive or negative does not matter, for their response signifies the NGOs’ legitimacy. The power that comes from their use of accountability politics and the boomerang effect, in addition to the legitimacy that comes from the state and public, endows NGOs with authority. They have a growing role in the world, as “important agents are not social movements, but NGOs” (Kaldor 589). This shift is largely due to two unique characteristics of NGOs. First, because NGOs work within the framework of social issues, they sometimes have more legitimacy than the state in the minds of some members of the public (Risse 272). These members of the public may consider information circulated by NGOs to be less biased than information disseminated by states and state-controlled structures. States are sometimes perceived to push an agenda favorable to themselves at the expense of social issues, such as the environment. Second, there are issues, such as pollution and human trafficking, which can only be solved on a regional or global scale. Therefore, in setting global policy agendas, NGOs, as transnational actors, are often able to contribute more effectively than states to efforts surrounding these issues (Risse 268).

II. The Perception of NGOs in Russia

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, NGOs helped fill a part of the welfare gap in Russia (Zabolotnaya 44). While Russia was restructuring, the US and Europe called for stronger global ties and for the growth of transnational actors. These two conditions supported an influx of NGOs in Russia, and with new reforms, elements of globalization and global civil society followed (Zabolotnaya 47).

The legacy of the USSR and its collapse also helped create the current social and legislative environment for NGOs in Russia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, some liberal activists from the anti-communist opposition supported the idea of global civil society, and therefore, NGOs.(Zabolotnaya 45). NGOs became associated with these anti-communist activists, who were eager to work with the West. However, in the turmoil of the 1990s, many Russians began to associate these pro-Western liberals and the ideals they espoused with economic collapse and near-political anarchy, which also characterized Russia at that time. Many citizens, and later the Russian government itself, began to distance themselves from Western ideals, and the growing idea of Western-style civil society naturally lost footing in Russia.

Andrey Makarychev wrote “Civil Society in Russia: between the State and the International Community” while he was a professor of political science at the Linguistics University of Nizhny Novgorod. In it, he argues that there are two general concepts that describe transnational actors in Russia. One is the idea that transnational actors are “embedded into the regime of functioning political actors, most of all, as their peripheral agents” [1] (Makarychev 31). In other words, Makarychev claims that existing political actors, such as states, are perceived as using transnational actors as instruments, and thus NGOs can be seen as foreign agents in Russia. As Galina Zabolotnaya, associate professor of political science at Tyumen State University, writes, “The unjustified hopes in an active civil society spawned discussions about its cultural perimeters (“West” or “East”)…”[2] (47). Thus, while some in the USSR argued that liberal, democratic policies would eventually lead to a stronger economy and society, others felt that, at least in the short term, they had created chaos and ruin. Furthermore, many NGOs, which represented the ideals of liberal democracy, originated in the West and were perceived as outsiders to the old Soviet system. Thus, their association with foreign entities, along with the fact that their appearance corresponded with the destruction of the old system and the decline of the national economy, helped bring Makarychev’s first concept into being: NGOs, as transnational actors, are seen as “peripheral agents” of foreign powers who may have incentive to better their own geopolitical position at the expense of Russia’s.

Makarychev’s second concept is that the Russian state believes Russian actors should primarily develop intellectual products that “would primarily be in demand in the region or country” [3] (Makarychev 32). In other words, the government only gives Russian transnational actors, such as NGOs, freedom to provide services for local or domestic Russian civil society. Meanwhile, NGOs relying on global civil society and neglecting to actively develop local Russian support, bolster the perception of NGOs as foreign agents, in accordance with Makarychev’s first concept of NGOs.

The Soviet legacy also affects Makarychev’s second concept of NGOs as service providers, since some Russians still expect the state to provide for them and therefore see little need for NGOs. Zabolotnaya explains how Russian lawyers, when examining the Russian government’s new role, enforced the idea that everyone should receive their subsistence from the state—in essence, for the Russian government to be Russian civil society (48). The current Russian Constitution, in fact, demands that the Russian government play the role of the ultimate guarantor of housing, education, and even access to culture for all Russians (Chapter). The Russian government has made moves to support NGOs that serve this purpose. For instance, it supports the movement “Civil Dignity”,[4] which hosts a grant contest for NGOs every year. One of the movement’s main goals is “to help the state increase the level and quality of people’s lives…”[5] (OOD). Therefore, NGOs that provide welfare services to assist citizens and develop local civil society can receive governmental support and funding. In this way, they can also be perceived as legitimate by some Russian citizens, which contrasts with how transnational actors typically gain public support. This is unsurprising, however, due to most Russians’ perception that the state should provide for society.

III. Russia’s NGO Legislation in Practice

The Foreign Agent Law demonstrates the precision of Makarychev’s concepts. The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law provides an accurate description of the complicated legislation:

The law requires all NCOs [/NGOs] to register in the registry of NCOs, which is maintained by the Ministry of Justice, prior to receipt of funding from any foreign sources if they intend to conduct political activities. Such NCOs are called ‘NCOs carrying functions of a foreign agent’ (NGO).[6]

To enforce the law, the Russian government first increased fines for failing to register as a foreign agent by 150 and then by 300 times the original amount, meaning fines can now reach up to a maximum of $142,000 (NGO). Such a large sum can force a non-profit to close (Russia: Year). In addition, the law gives the government “supervisory power,” or the ability for members of the Russian government involved with NGO legislation to oversee NGO operations, which clearly interferes with the normal day-to-day operations of NGOs (NGO). One final important part of the Foreign Agent Law is that it restricts funding from foreign or international organizations. The law makes grants from such sources taxable income unless the foreign source is on an extremely exclusive list, pre-approved by the Russian government through Russian Presidential Decree #485 of June 28, 2008 (Grabel). Only fourteen multinational organizations have made it onto the list, while other organizations have to apply per grant (Grabel).

Four major NGOs have been fined under the new law: Golos, Kostroma Center for Public Initiatives Support, The Memorial Anti-Discrimination Center (widely known as “Memorial”), and the Side by Side LGBT film festival. Golos, which closed for a time after the fine it faced effectively bankrupted it, worked for fairer and more transparent elections and greater freedom of speech. The Russian government fined Golos for receiving a grant from the Norwegian Helsinki Committee for work involving Russian election monitoring. The Kostroma Center hosted a roundtable on US-Russia relations and invited a member from the US Embassy. Memorial produced a report with foreign funding from the International Federation of Human Rights, which is primarily funded by Western European organizations, including the European Commission. It detailed police abuse of ethnic Roma individuals, migrants, and civil activists. This, from the government’s perspective, could destabilize the legitimacy of the police force. Finally, Side by Side, an international film festival developed and funded by the US-based organization Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), published a brochure titled, “International LGBT Movement: from Local Practices to Global Politics” (List).

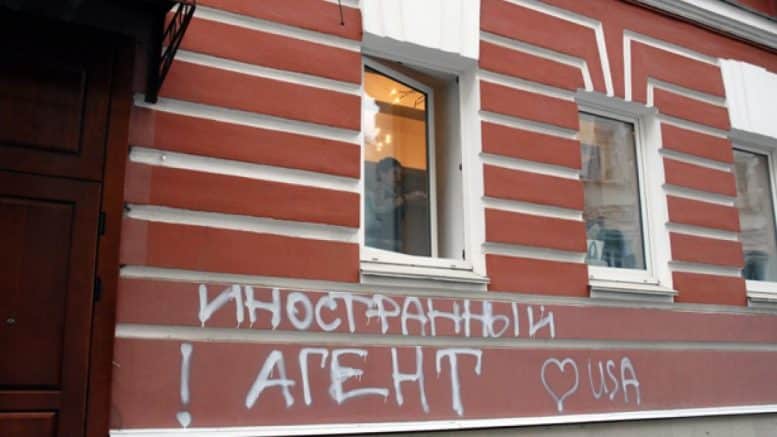

Of particular concern to NGOs is the fact that Russia’s 2012 Foreign Agent Law uses the term “foreign agent” or «инностранный агент». This has connotations of treason and subversion in Russia, as the term was also used in the USSR to refer to those involved in such activities (Factsheet). As the effectiveness of an NGO often stems from public trust and perceived legitimacy, this is obviously an issue that could directly affect the functioning of NGOs.

Many NGOs have refused to register, declaring it an insult to their institution, which they consider to be far from treasonous or subversive. One NGO, the Committee Against Torture (CAT), was recently accused of agreeing to the Foreign Agent Law restrictions in exchange for a Russian Presidential Grant. To this, CAT director Igor Kalyapin responded:

…I will never, whatever the circumstances, agree to the shame of calling myself something I have never been – a foreign agent… Under my leadership, the Committee Against Torture has always acted in the interests of Russia, its nationals and other people living in our country (Prusakov).

Kalyapin’s passionate testimony demonstrates how offensive the term “foreign agent” is. Many other NGOs and critics support this sentiment (NGO ‘Foreign’). For instance, when the Russian NGO Memorial was prosecuted for refusing to register as a foreign agent, representative attorney Cyril Koroteev argued, “the term ‘foreign agent’ is offensive and causes negative connotations”[7] (Mikhailova). They additionally claimed that despite foreign funding, they are working always for the betterment of Russia, not for other countries (Mikhailova). Another NGO, The Alliance of the Women on the Don, has issued similar statements (Russia: Year). They attempt to demonstrate that they provide welfare support to society, rather than act as “foreign” or “peripheral” agents.

Makarychev’s concepts can help to explain the hostility toward NGOs most recently manifested in the Foreign Agent Law. RIA Novosti, one of the largest news agencies in Russia, reports that Putin and his government enacted this law simply in response to perceived anti-Russian US laws, such as the Magnitsky Act from December 2012 (Russia Comes). Sergei Magnitsky investigated a tax fraud case involving Russian officials, then was investigated himself and imprisoned by the same officials he was investigating. Mr. Magnitsky later died after a severe beating left him with internal injuries that went untreated as he was still in pre-trial detention. The Magnitsky Act, passed in the US in response to the case, forbids those officials seen as responsible for perceived human rights abuses, such as the death of Mr. Magnitsky, from entering the US and freezes any of their funds held in US institutions (Kramer). Russia’s Foreign Agent Law was passed just months after the Magnitsky Act. To Russia, the Act symbolized the interference of the West, and in particular the US. In response to the Magnitsky Act, both Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and foreign policy adviser Yuri Ushakov have “promised a retaliatory response to the Act, calling it ‘anti-Russian’ and intrusive in the country’s internal affairs” (Wagner).

Putin’s repeated sentiments professing a need to protect Russia’s sovereignty further support this idea. In his speeches, he often makes remarks such as “Russia’s sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity are unconditional. These are red lines no one is allowed to cross” (Meeting). Albeit this is normal political rhetoric in most countries, Putin in particular often emphasizes protecting sovereignty, and NGOs typically draw authority and power away from states by taking over or calling attention to shortcomings in services that are often provided by the state, such as assisting the elderly.

Veronica Krasheninnikova, head of the Institute of Foreign Policy Studies and Initiatives, believes that “Washington had advised Russia’s nonprofit groups to defy the new [Foreign Agent] law, forcing the Russian government to take harsh measures” (Barry). Furthermore, Putin has suggested that on occasions such as the 2011 democratic protests, foreign powers were paying Russian citizens to support the opposition (Sandford). Due to this perceived threat to Russian sovereignty, there is deep mistrust in Russia toward NGOs as potential “peripheral agents,” representing growing Western, primarily American, interference and dominance.

Given the historical context of the role of NGOs in Russia, and given the timing and wording of the new Foreign Agents law, it would appear that the current Russian authorities view many NGOs as “peripheral” or “foreign” agents and enacted the law to stem the West’s perceived interference by limiting their influence. In addition to the Foreign Agent law, the government also reintroduced the criminalization of “defamatory statements,” which seriously hinders an NGO’s ability to “name and shame” actors (NGO).

The current situation for NGOs under the new laws is disheartening. Yuri Dzhibladze, president of the Center for Democracy and Human Rights, writes:

As the law institutes a system of inspections, more than a thousand NGOs have been inspected of which more than 300 have received warnings claiming they are engaged in foreign activities such as receiving funds from abroad or maintaining contact with non-Russian NGOs (Report).

In addition to the temporary closure of Golos, three other NGOs closed rather than attempt to fight the label (Russian: Repeal). At least ten have been taken to court “for failing to register as an ‘organization performing the functions of a foreign agent’” (Russia: Year). Five others have been taken to court for documentation violations after inspections, and an additional ten organizations have been ordered to comply with the law by government inspectors; 37 others have been officially warned (Russia: Year).

Since the passage of the law, little has changed in favor of NGOs. There has also been visible negative public opinion toward NGOs, mostly due to the association with the term “foreign agent”. For instance, shortly after the law was enacted, the words, “Foreign Agent (loves) USA” were graffitied onto a building occupied by Memorial, a Russian human rights NGO (Foreign). With some pressure from continual lawsuits and complaints from NGOs and activists, Putin has admitted that the Foreign Agent Law needs to be reformed in some way, but no such reform has come (Russia: Repeal). Rather, the government has recently strengthened its own power over NGOs, giving the Justice Ministry the authority to independently register NGOs as foreign agents (Justice). NGOs are today severely hindered in day-to-day operations by limited funding, the state’s new supervisory powers (and the increased paperwork this creates), and the criminalization of “defamatory statements.” They continue to face fines, court summons, and potential shutdowns.

IV. Factors in NGO Success

Despite this inhospitable atmosphere, some NGOs in Russia continue to operate successfully. These NGOs avoid the current legislation by using local methods to help society and work toward developing local civil society. Successful NGOs’ goals are directed toward aiding Russian society in ways that the majority of Russians accept, avoiding “western values” such as LGBT rights (which likely complicated the case of the Side by Side film festival described above).

The phrasing of the Foreign Agent Law supports this; an NGO must only report funding “if they intend to conduct political activities.” The 2012 Stability Index of St. Petersburg NGOs, published annually by the Center for NGO Development, found that “[h]uman rights organizations have been most vulnerable. Socially oriented NGOs, on the contrary, receive more governmental support, which is reflected in legislation.”[8] (4) What is most encouraging about this conclusion is that NGOs can still be successful and work with foreign partners in reciprocal partnerships, allowing them to remain members of global civil society. In this way, European partners have been most helpful to Russian NGOs.

On the other hand, relying too heavily on Western allies for advice may contribute to Russian society seeing NGOs as intruders and as non-Russian. Russian NGOs have admitted that “some of their present difficulties are caused by their attempts to adapt to the Western models” (European 46). For instance, the LGBT movement in the USSR noticeably began in the 1980s and developed further under the liberal rule of Boris Yeltsin. According to We’ve Waited Long Enough, a pamphlet published in 1993, there was great optimism for LGBT rights. At first, domestic LGBT activists successfully campaigned for the decriminalization of homosexuality under Russian law. They backed Yeltsin and garnered some support from him (Russian).

More recently, the LGBT movement has suffered in Russia as it has grown more prevalent in international society. In 2007, only 19 percent of respondents believed that homosexuality should be punishable by law, but by June 2013, the figure rose to 42 percent (Sewell). Although there are multiple reasons for this increase, such as government rhetoric, the shift also occurred as the LGBT community became more openly assertive. In 2005, the NGO Gay Russia was founded. In 2006, the movement began to push for legal, annual gay pride parades, as to this day only illegal small parades are held (Senzee). Such parades, which are legal cornerstones of the LGBT movement in the US and Europe, can turn conservative Russians against members of the LGBT community (Duvernet). Also in 2006, Gay Russia helped found the Russian LGBT Network, a larger NGO. According to the network’s website, the organization relies heavily on foreign funding. Its mission statement proclaims:

The Russian LGBT Network strives to get the Russian Federation to obey international norms regarding LGBT people. We enhance the international visibility of the present situation on human rights for LGBT people in Russia and provide transparency where the country’s obligations assumed within the framework of its international agreements are concerned… The Russian LGBT Network also actively cooperates with international and foreign NGOs, participates in various coalitions and initiates coalitions itself.

By speaking of holding Russia to international norms and wishing to “enhance the international visibility,” the organization effectively shifts its focus from local to global. This matches Makarychev’s definition of when an NGO can be perceived as acting as a “peripheral agent.” Therefore, it is not surprising that the LGBT movement and associated NGOs have found themselves facing increasing hostility, not only from conservative sectors of Russia’s society, but also from the Russian government.

Successful NGOs in Russia act more like service providers than builders of international civil society. One such effective NGO is the Center for NGO Development for the North-West Region of Russia (CRNO); the following information comes directly from its website (crno.ru). As a rather large NGO, it acts as a resource center for 150-200 NGOs in its region. It was founded in the tumultuous 1990s, and it continues to receive domestic and foreign funding to work on initiatives including several successful annual projects. Many projects educate other NGOs on better practices for their organizations, such as improving financial literacy, increasing corporate sponsorship, and encouraging greater communication among Russian NGOs. Projects run by the CRNO are often supported by the Russian Federation as efforts to educate Russian NGOs to be self-sufficient, actively seek funding from the Russian state and private donors, and create a more connected Russian civil society.

Another successful NGO is the German-Russian Exchange organization in St. Petersburg; the following information comes from its website, www.obmen.org. The goal of the organization is to share information and experience between Russia and Europe in order to build a better civil society in both locations. This NGO is funded and supported by both European and Russian organizations, such as the CRNO and the Youth Exchange in Switzerland. Even now, the German-Russian Exchange is developing new projects. One of the latest projects, known as “School Exchange,”[9] is an exchange program for German and Russian school students. The goal is to break down misconceptions between countries and open up the minds of students (Host). In addition to this specific exchange program, the German-Russian Exchange has other similar initiatives, and the organization has continued to receive funding from both its international and domestic partners.

Thus, NGOs can have successful partnerships with foreign organizations and remain members of global civil society. European organizations in particular, such as the European Union and Council of Europe, encourage NGOs in former Soviet countries to implement practices that would be appropriate to match local needs. Makarychev notes that after the collapse of the USSR, the Central and Eastern European countries, which integrated into the European structure, gained innovative techniques via Europe’s “knowledge-driven economy, open learning, and/or learning by interaction” (28). Patrice McMahon, an associate professor in political science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, has stated that one of the benefits of the EU’s support for the Hungarian women’s movement is that it takes out Western bias and funds projects to focus on average citizens (51). She adds, “The European Union’s attitude toward women’s issues is an excellent example of the difference that international actors can make” (51). Most European partners do not push for an orthodox following of the European model, but they continue to fund projects to match local needs.

The Center for NGO Development, like other NGOs, has had a recent shift in international funding. In 2013, Svetlana Pozdnyakova, project manager at CRNO, wrote: “American foundations are leaving Russia, while on the contrary, European ones are strengthening their position, and so there is a greater possibility to receive financial support from the European Union”[10]. One remaining American benefactor is the Mott Foundation, which encourages its sponsored organizations to develop community organizations “that use local resources to meet local needs” (Community). European partners exemplify this practice. A project funded by the Council of Europe and the Nordic Council called “The Promotion of the Principles of Good Governance in the North-West Region of the Russian Federation,” is one of the more recent projects at the CRNO. According to the Nordic Council, the purpose of this initiative is:

Studying of European best practices and adaptation of key principles of standardisation and public services assessment to the Russian regional and local context [to] promote efficiency and quality of public institutions, increase levels of cooperation with citizens, political parties, interest groups and civil society institutions (Promoting).

This project challenges the practices of the state, but it does so in such a way as to boost Russian civil society and only make “adaptations” to the system. It encourages Russian NGOs to analyze European best practices and implement relevant ones in order to enhance communication between NGOs and the Russian government. The CRNO also collaborated with the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Presidential Administration on this project, which lends it further domestic legitimacy. In this way, a foreign-funded NGO project is able to function successfully in Russia.

The CRNO, in its 2013 annual report about the status of NGOs in St. Petersburg, devotes an entire section to “The European Experience with a Russian Accent” [11] (Tarasenko 16). One of the most interesting claims of Anna Tarasenko’s article is that “the European experience… in fact, has been copied to solve problems of reforming the Russian social sphere”[12] (16). She finishes the section by stating that, based on the European experience, Russia should strive to develop three better practices for civil society: the transfer of state functions to civil society the reform of the public sector (allowing NGOs to be “low cost, autonomous and public institutions”);[13] and government programs to support NGOs (17). The policies mentioned are focused on greater involvement with Russian society as service providers. In this example, not only is Tarasenko encouraging Russian civil society to look to Europe as a model, but she is also suggesting policy based on it. The “European experience,” however, is still put into a Russian context, as the very title of the section implies that the European experience, when applied to Russia, will be altered.

The European Union also provides legitimate international support to Russian civil society in ways that do not encouraging the perception of NGOs as “peripheral agents,” thus helping them to remain involved in global civil society. Under the Medvedev administration, European NGOs reestablished their connection to Russia, stating that the climate for civil society in Russia was ripe for EU involvement (EU-Russia). The first crucial point that EU NGOs decided on was “[a] critical reassessment of EU assistance programs for Russian civil society with an aim to shift from an assistance mentality to genuine partnership” (EU-Russia). This shift in mentality clearly reflects NGOs’ fear of entering into an asymmetrical partnership, which could give them the appearance of being a “peripheral agent.” With the EU NGOs, such as the Association of Local Democracy Agencies in Brussels, the German Russian Exchange in Berlin, and the Slovak Foreign Policy Association in Bratislava, both Russian and EU NGOs agreed to these terms. In 2010, Russia and the EU founded the EU-Russia Civil Society Forum (EU-Russia), which has so far achieved some success. One of the most significant achievements was its ability to assist Golos, the NGO which had officially closed in June 2013. However, it quickly reopened, this time as a “movement” rather than an “association.” The two classifications operate under different contexts within Russian law. A sub-branch of the EU-Russia Civil Society Forum, the European Platform for Democratic Elections (EPDE), made Golos (the movement) a Russian member. In September 2013, this new Golos, as a partner of the EPDE, reviewed local Moscow elections without garnering much government attention (EDPE). The revival of Golos in Russia after its initial closing is a good indicator that the partnership with the EU may contribute to future successes.

A very significant aspect of the EU-Russia Civil Society Forum was the pledge to support NGOs via the European Court of Human Rights, a supranational institution of the Council of Europe. Since Russia is a member, it must pay attention to the Court’s decisions and cannot accuse NGOs of seeking help from the West for taking their grievances to the court. The Council of Europe, for its part, “remains on the watch for the ‘deteriorating situation of NGOs’” in Russia (Report). Russian NGOs are now able to sue Russia if they believe they have been treated unfairly under the Foreign Agent law. Even the threat of a lawsuit can help an NGO, such as the Human Rights Center in Yekaterinburg. The Center successfully won its case against prosecutors who issued the Center a warning for not registering as a foreign agent, as the Center receives support from several international organizations, including the EU and Council of Europe (Ekaterinburg; Sutyazhnik). Many factors contributed to the victory, but one was the ability to continue “the case by means of an application to the European Court of Human Rights” (Ekaterinburg). Thirteen other NGOs have taken advantage of this institution and filed a joint complaint about their treatment under the new law; they are awaiting their trial (Russia: Repeal). The opportunity for NGOs to, via a legitimate European institution, seek redress of what they consider unfair actions taken by the Russian government is another good sign for the future of Russian NGOs.

V. Conclusions

Despite the current challenging environment, some NGOs have managed to be successful. As long as they provide services to citizens, develop local civil society, and avoid newsworthy political conduct, they can minimize the impact of the “peripheral” or “foreign” agent label. Some have argued that if NGOs follow these steps and yield to governmental pressure, the NGOs lose their impartial nature and simply become another branch of the government. While this is in part true, given the hostile atmosphere in Russia toward NGOs, slowly developing local civil society is the most promising way to provide a legitimate, homegrown platform from which NGOs can expand in the future. NGOs can still challenge the government to a degree, such as in the case of the Committee Against Torture, and retain governmental support. These successful organizations can also have international partnerships and be a part of global civil society.

Based on the relationships among the EU, Council of Europe, and Russian civil society, international partners must allow Russian NGOs to match local needs, rather than push a certain agenda or method. Stephen Sestanovich, a senior fellow for Russian and Eurasian Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, argues that if the US treated Russian organizations more like equals, then the US could help Russian civil society just as well as Europe does (Putin Critics). Direct pressure only causes Russia to stiffen against what it perceives as challenges to its independence and sovereignty. It works to preserve these, in part, by restricting the work and funding of NGOs in domestic affairs. As long as international organizations treat their Russian counterparts as equal partners, then international support can exist and benefit both local Russian and global civil society.

Works Cited

Barry, Ellen. “As ‘Foreign Agent’ Law Takes Effect in Russia, Human Rights Groups Vow to Defy It.” New York Times 21 Nov. 2012, n. pag. Web. 14 Dec. 2012.

“Chapter 2. Rights and Freedoms of Man And Citizen | The Constitution of the Russian Federation.” The Constitution of the Russian Federation. Garant-Internet, 2001. Web. 07 July 2014.

Chaykovskaya, Evgeniya. “Putin Addresses the Duma.” Themoscownews.com. The Moscow News, 20 Apr. 2011. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

“Community Foundations.” Mott.org. Mott Foundation, 2010. Web. 05 Dec. 2013.

Duvernet, Paul. “Being Gay in Today’s Russia.” Rbth.ru. Russia Beyond The Headlines, 17 July 2013. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

“Ekaterinburg NGO Wins ‘Foreign Agent’ Case.” Hro.rightsinrussia.info. Rights in Russia, 20 Nov. 2013. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

“EPDE and Its Member Golos Start Observing the Local Elections.” Epde.org. European Platform for Democratic Elections, 8 Sept. 2013. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

European Commission. Shaping Actors, Shaping Factors in Russia’s Future. New York: St. Martin’s, 1998. Print.

EU-Russia Civil Society Forum. For a New Start in Civil Society Cooperation with Russia. EU-Russia Civil Society Forum, 23 Mar. 2010. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

“Factsheet.” Freedom House. Freedom House, n.d. Web. 30 June 2014.

““Foreign Agents” Law Now in Effect – NGOs’ Premises Vandalised.”Civilrightsdefenders.org. Civil Rights Defenders, 21 Nov. 2012. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

Grabel, Brittany. “Russia.” Council on Foundations. Council on Foundations, May 2014. Web. 30 June 2014.

“Justice Ministry Adds 5 More Russian NGOs to ‘Foreign Agent’ List | News.” The Moscow Times. The Moscow Times, 9 June 2014. Web. 13 June 2014.

Kaldor, Mary. “The Idea of Global Civil Society.” International Affairs 79.3 (2003): 583-93.Print.

Keck, Margaret E. and Kathryn Sikkink. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Ch. 1 and 3. 1998. Print.

Kramer, David J., and Lilia Shevtsova. “What the Magnitsky Act Means.” Freedomhouse.org. Freedom House, 19 Dec. 2012. Web. 14 Jan. 2014.

“List of Russian NGOs Named “Foreign Agents” (updated)” Yhrm.org. Youth Human Rights Movement, 12 May 2013. Web. 29 Nov. 2013.

Machalek, Katherin. “Factsheet: Russia’s NGO Laws.” Freedomhouse.org. Freedom House, 2012. Web. 29 Nov. 2013.

Makarychev, Andrey S. “Гражданское общество в России: между государством и международным сообществом. [Civil Society in Russia: between the State and the International Community]” Ed. Alexander Y. Sungurov. Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla. Публичное пространство, гражданское общество и власть [The Public Sphere, Civil Society, and Power]. Moscow: Russian Association for Political Science, 2008. 19-32. Print.

McMahon, Patrice. “What a difference they have made: international actors and women’s NGOs in Poland and Hungary.” The Power and Limits of NGOs: A Critical Look at Building Democracy in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. By Sarah Mendelson and John K. Glenn. New York: Columbia UP, 2002. 29-51. Print.

Mikhailova, Anastasia. [Михайлова, Анастасия.] “”Мемориал” не убедил суд, что он не иностранный агент.” [“”Memorial” Did Not Convince the Court that it is not a Foreign Agent”] РБК. РБК [RBK], Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla. 23 May 2014. Web. 07 July 2014.

“Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club.” Eng.kremlin.ru. Russian Federation, 19 Sept. 2013. Web. 29 Sept. 2013.

Nelson, Paul. “New Agendas and New Patterns of International NGO Political Action. “Creatinga Better World: Interpreting Global Civil Society. Ed. Rupert Taylor. Bloomfield: Kumarian, 2004. 116-32. Ebrary. Web. 8 Mar. 2013.

“NGO ‘Foreign Agents’ Law Comes into Force in Russia.” RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti, 20 Nov. 2012. Web. 07 July 2014.

“NGO Law Monitor: Russia.” Incl.org. International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, 20 Aug. 2013. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

“NGOs in Russia Could Be Labeled ‘Foreign Agents’ Without Their Consent | News.” The Moscow Times. The Moscow Times, 4 June 2014. Web. 6 June 2014.

“Only One NGO Registered Under Russian Foreign Agent Law.” RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti, 14 Feb. 2014. Web. 06 July 2014.

Pozdnyakova, Svetlana. E-mail interview. Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla. 5 Dec. 2013.

“Programs.” Lgbtnet.ru. Russian LGBT Network, 2012. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

“Promoting Good Governance Principles in North-West Russia.” Norden.ru. Nordic Council of Ministers, 2012. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

Prusakov, Anton. “Committee Against Torture Receives Its First Presidential Grant Reports Kommersant Newspaper.” Pytkam.net. Committee Against Torture, 03 Sept. 2013. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

“Putin Critics Urge Fresh US Support for NGOs in Russia.” En.ria.ru. RIA Novosti, 13 June 2013. Web. 04 Dec. 2013. <http://en.ria.ru/russia/20130613/181650831.html>.

“Report: Putin’s Crackdown on Civil Society in Russia – Can the EU Do Anything to Help?” EU- RussiaCentre.org. EU-Russia Centre, 16 Oct. 2013. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

Risse, Thomas. Transnational Actors and World Politics. In Zimmerli, Walther Ch., Klaus Richter, Markus Holzinger (eds.). Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance. Berlin: Springer. 2007. Print.

“Russia Comes One Step Closer to Banning US-Funded NGOs.” En.ria.ru. RIA Novosti, 19 Dec. 2012. Web. 17 Dec. 2013.

“Russia: A Year On, Putin’s ‘Foreign Agents Law’ Choking Freedom.” Amnesty.org. Amnesty International, 20 Nov. 2013. Web. 29 Nov. 2013.

“Russia: Repeal “Foreign Agents” Measure.” Hrw.org. Human Rights Watch, 21 Nov. 2013. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

“Russian Gay History.” Community.middlebury.edu. Middlebury College, n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

Sandford, Daniel. “Putin: Election Undoubtedly Reflected Public Opinion.” Bbc.co.uk. BBC, 15 Dec. 2011. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

Senzee, Thom. “9 Unexpected Places Where Pride Flags Flew During Pride Month.” Advocate.com. Advocate, 30 June 2014. Web. 07 July 2014.

Sewell, Patrick. “Understanding Russia’s Perspective on “Gay Propaganda”” Rbth.ru. Russia Beyond the Headlines, 14 Aug. 2013. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

“Sutyazhnik (Ekaterinburg – Sverdlovsk Region) – Rights Groups in Russia.” Sutyazhnik (Ekaterinburg – Sverdlovsk Region). Rights Groups in Russia, n.d. Web. 30 June 2014.

Tarasenko, Anna. V. «Анализ практик поддержки СО НКО Санкт-Петербурга по данным реестра получателей государственной поддержки» [Analysis of the Practices Supporting the Socially-Oriented NGOs of St. Petersburg according to the Registry of Recipients of State Support] Негосударственные некоммерческие организации в Санкт–Петербурге 2013 [Non-governmental, Non-commercial Organizations in St. Petersburg 2013]. Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla. St. Petersburg: Center for NGO Development, 2013. 15-23. Print.

“Violations by Article and Respondent by State.” Echr.coe.int. Europe Court of Human Rights, 2012. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

Wagner, Daniel. “The Magnitsky Act and Implications for Russia-U.S. Relations.” TheHuffingtonPost.com. The Huffington Post, 17 June 2012. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Zabolotnaya, Galina M. “Социальный и политический капитал гражданского общества в условиях посткоммунистического перехода: региональный аспект. [Social and Political Capital of Civil Society in the Conditions of Post-communist Transition: Regional Aspect]” Ed. Alexander Y. Sungurov. Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla. Публичное пространство, гражданское общество и власть [The Public Sphere, Civil Society, and Power]. Moscow: Russian Association for Political Science, 2008. 44-55. Print.

Индекс устойчивости НКО 2012 [The Stability Index of NGOs 2012]. Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla Rep. St. Petersburg: Center for NGO Development, 2013. Print.

“ООД ГРАЖДАНСКОЕ ДОСТОИНСТВО. [OOD Civil Dignity]” Trans. Jacqueline Dufalla Гражданское достоинство [Civil Dignity]. Гражданское достоинство [Civil Dignity], 2013. Web. 11 Mar. 2014.

“Принимающие школы в России. [Host Schools in Russia]” Немецко–Русский Обмен[German-Russian Exchange]. Немецко-Русский Обмен [German-Russian Exchange], 2014. Web. 31 July 2014.

Footnotes

[1] встроенных в режим функционирования политических субъектов, чаще всего – в качестве их периферийных агентов