The USSR was a nearly unstoppable force in hockey. Picture from savok.ru

While Russia’s political history has been tumultuous and unpredictable, one thing has remained an unfaltering constant: Russians are good at hockey. While Brezhnev dealt with the fiasco that was the Afghan War, Viktor Tikhonov led the Soviet Union’s national ice hockey team (Сборная СССР по хоккею с шайбой) to victory, after victory, after victory. Winning almost every world championship and Olympic game from 1954 to 1991, the Soviets are the most dominant team in the history of international play.

According to the socialist principles espoused by the Soviet government, the success of the society was more important than the success of the individual. The Soviet style of hockey was thus based on not having every player seen as a star, but instead utilizing the strengths of each player to create an almost indestructible machine – and a gold medal magnet. It’s no surprise that some members of the Soviet national team are still regarded as some of the best to ever play their position: right wing Sergei Makarov, goaltender Vladislav Tretiak, and defenseman Vyacheslav Fetisov. When the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF)comprised a “starting line-up of the century” last year, four of the six chosen players once played for the Soviet Union’s national team, another was from Canada, and the other was from Sweden.

Viktor Tikhonov was not only the coach of the national team but also coached the Red Army’s team in the Soviet League, CSKA Moskva (ЦСКА Москва). Tikhonov held the rank of general in the Red Army and ran his team accordingly. They practiced ten to eleven months per year and lived in army barracks during the time they practiced, even if they were married. With such “dedication,” CSKA Moskva dominated the Soviet League, winning the championship 32 times in the league’s 46 year existence.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Soviet League has gone through a series of metamorphoses. The first was the brief appearance of the International Hockey League (1992-1996) which replaced the Soviet League. This turned into the Russian Superleague(Чемпионат России Суперлига), which initially was a Russian-only league, but at the end of the 2007-2008 season, the Russian Superleague expanded to include three countries outside of Russia: Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Latvia. It was then rechristened the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) (Континентальная Хоккейная Лига) to reflect its broader membership (and which is spelled with a “K” in English, possibly to deferentiate its initials from the Canadian Hockey League). Even though the KHL has only finished one season, the IIHF already considers it to be the strongest league in Europe. Vyacheslav Fetisov, who formerly played on both the Soviet national team and in North America’s National Hockey League (NHL) and who is currently the KHL’s CEO, states that: “In five years, we will be able to compete with the National Hockey League.”

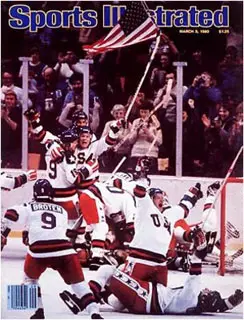

A 1980 Sports Illustrated cover showing the American team celebrating victory over the Soviets in what was then regarded as a nearly impossible feat and is still regarded as one of sport’s biggest upsets. “The Miracle on Ice,” as it is now known, even became the subject of the Disney film Miracle.

Upon first glance, Fetisov’s goal seems quite lofty, but after a closer look it proves to be quite attainable. Three months ago, the Russian national team added to their numerous international victories, winning the 2009 IIHF-sponsored World Championship, in which national teams from around the world compete. National teams can consist of any player who holds the same nationality of the team, regardless of which country they currently play in. Out of the 26 players on the Russian national team’s roster, 15 of them played for KHL club teams, and the other 11 played for NHL clubs that weren’t competing in the simultaneous NHL playoffs. Even the captain of the national team, Aleksei Morozov, plays in the KHL. During the regular club season, Morozov was number three in total points scored; he also led his team, Ak Bars Kazan, to victory in the KHL Championship. Ak Bars is most often written in Russian Cyrillic (Ак Барс Казань), although the name itself translates in Tatar (which has its own alphabet) as “The Kazan Snow Leopards.”

Among the other notable KHL players who participated in the national team are: Sergei Mozyakin, Aleksei Tereshchenko, Aleksandr Eremenko, and Danis Zaripov. Mozyakin plays for Atlant Moskva (Атлант Москва), and was the league leader in points. Tereshchenko plays for Salavat Yulaev Ufa (Салават Юлаев Уфа), and held the top plus/minus at +41. When a goal is scored, every player on the ice for the scoring team gets a “plus” and every player on the ice on the opposing team gets a “minus.” The “plus/minus” for an individual player is calculated by tallying these points, so a high plus total is taken to mean that a player is strong on defense. Tereshchenko was also in the top ten for points scored. Zaripov plays for the current champion, Ak Bars Kazan, and was number five in points scored. And Eremenko, a goaltender, plays for Salavat Yulaev Ufa and was second in the number of wins.

Logically, if the Russian national team (with over half the team playing in the KHL) can successfully compete at the international level and win back to back World Championships, chances are they can eventually compete with the NHL.

The NHL is considered a perpetual thorn in Russian hockey’s side. During Soviet times, there was a fear that players would defect to play in the United States, but now this has turned into more of a resentment that the NHL “steals” young talent. Many Russian hockey enthusiasts don’t think it is kosher to train all of these young boys, make talented, driven hockey players out of them, and then ship them off to the land of McDonald’s and dollar signs.

The logo of the modern-day Kontinental Hockey League.

However, the value of Russian players is obvious for the NHL. Ironically, in a North American based league, four Russians have been among the top ten scorers for the past few years. They are: Aleksandr Ovechkin, Evgeni Malkin, Ilya Kovalchuk, and Pavel Datsyuk.

Aleksandr Ovechkin, for instance, is one of Russia’s best known hockey players, and is currently signed with the Washington Capitals, an NHL team, for the next twelve years. Aleksandr Ovechkin is the complete antithesis of “old Soviet hockey” which was generally associated with stoicism. The passion Ovechkin exudes on the ice is almost tangible. After every goal he scores he rushes to slam himself into the boards at the side of rink. Ovechkin has been a fixture on the Russian national team since 2005, which is also the same year he entered the NHL. During that first year, Ovechkin won the Calder Memorial Trophy (the Rookie of the Year award), and during the subsequent four years has been among the top point scorers in the league.

Some Russians who had been recruited to the NHL are now starting to return home and play for the KHL. Sergei Fedorov, for example, was the most successful Russian (in terms of points) to ever play in the NHL and was one of the first Russian players to defect from the Soviet Union to play abroad professionally. While the Soviet team was the best team in the world, even better than the NHL, during the last years of the Soviet Union’s reign, the risk and fear of players defecting increased to alarming levels. It was so bad that Tikhonov would sometimes scratch his best players from the lineup and not allow them to participate in international play. The main reasons for players defecting were elemental—money and freedom from Tikhonov’s iron-fisted coaching style. In the summer of 2009 Fedorov turned down offers to stay in America in favor of moving back to Russia. Fedorov stated that he returned to make his father’s wish come true of having his two sons play on the same team together. On June 25, 2009, he signed a two year contract with Metallurg Magnitogorsk(Металлург Магнитогорск), the team his brother Fedor also recently signed with, and will join them in the upcoming season.

Alexander Radulov, far left, in 2009 after Russia won the IIHF World Championship for the second year in a row. Radulov scored the last goal in that match, putting Russia in the lead and earning Russia the cup.

Aleksandr Radulov also recently returned home, signing with Salavat Yulaev Ufa for the KHL’s inaugural season. In doing so he broke his NHL contract with the Nashville Predators. Adding to the controversy was the fact that the announcement of the deal came two days after the NHL and KHL signed an agreement stating that they would honor all existing contracts and would not “poach” players. The NHL claimed that the KHL had broken the agreement and signed Radulov illegitimately. The KHL claimed that Radulov’s contract was actually signed three days prior to the agreement with the NHL, and therefore his contract would remain in effect, and it has.

As of late, the KHL has been turning the tables on the NHL by more aggressively recruiting even their non-Russian players to sign with Russian teams. This issue of player “poaching” resurfaced again this past summer, with the signing of Czech forward Jiri Hudler to Dynamo Moskva (Динамо Москва) Hudler got his start in hockey by playing briefly for a Czech team before getting signed to the Detriot Red Wings in 2002. Hudler then signed a deal with Dynamo while he was a restricted free agent and undergoing salary arbitration, which would guarantee him at least a one year contract with the Detroit Red Wings. The NHL is currently contesting Hudler’s contract with Dynamo, and stated that because Hudler applied for salary arbitration, he already agreed to at least a one year contract with his current team. An appeal was filed with the IIHF, the worldwide governing body for ice and in-line hockey, but that body has not yet made an official ruling on this matter.

The grave of Alexei Cherpanov. Hundreds of fans attended the funeral of the 19-year old prodigy. Picture from KP.ru

Needless to say, since the KHL formed, tensions between them and their North American counterparts have been high.

While player scandals arising from “poaching” by teams on both sides of the ocean is an external problem for the KHL, its internal problems are a bit more serious. A few KHL teams have experienced financial hardships. One team, Khimik Voskresensk(Химик Воскресенск) declared bankruptcy and withdrew from competition for the 2010 season. Reports concerning teams being behind in paying the coaches’ and players’ salaries are constantly swirling, but rarely confirmed. Although these economic problems are nothing new (they carried over from the Russian Superleague), they will need to be addressed and dealt with if the KHL plans to fulfill their goal of competing with the NHL in five years’ time.

Another internal problem has been the high-profile story of Alexei Cherepanov‘s untimely death. On October 13, 2008, during a game with his club Avangard Omsk (Авангард Омск), Cherepanov came off the ice after playing a shift and collapsed on the bench minutes later. While ambulances are a mainstay at hockey games, the one designated for that game had already departed with another player. It took doctors a full 12 minutes to arrive, only to find out that their defibrillator’s battery was already drained. After he was briefly resuscitated at the rink, Cherepanov was ultimately pronounced dead after being taken to the hospital.

Cherepanov’s death came as a shock to many, and sparked rumors of doping and corruption in Russian hockey. The Russian Hockey Federation’s supervisory council launched an investigation into the young hockey player’s death. On December 29, 2008, investigators revealed that Cherepanov had suffered from myocarditis, a heart condition where not enough blood gets to the heart, and because of this condition he should never have stepped foot on the ice in the first place.

Russian hockey fans celebrate in Moscow after Russia’s 2008 IIHF World Championship victory. The slogan on the flag translates to “Russians Don’t Give Up!!!” Picture from Life.ru

The investigative committee claimed that the doctors would have had no reason to suspect that Cherepanov suffered from that particular ailment because his annual checkups did not hint at any heart problems. Cherepanov had been taking Cordiaminum, a type of medicine that increases circulation and thus combats the symptoms of the condition, but the team doctors had not prescribed this medication. The ruling stated that it appeared as if Cherepanov had been aware of his ailment and made attempts to conceal it in order to play. On July 15, 2009, the team doctors were acquitted of negligence charges.

Despite the challenges faced, KHL officials are seeking to correct the league’s problems and expand further into Western Europe over the next few years. As of right now, the KHL is in talks with four Swedish teams and with teams from Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic; it has been reported that the league is seeking to expand to a total of 30 teams. However, those plans may take a while to materialize: due to the current economic crisis, the Czech teams had to suspend their plans to join the League and the German teams that have been approached by the League have not made any concrete plans to join yet.

Many obstacles lie ahead for the KHL, but so far the foreseeable future looks mostly positive. Russia first produced talents such as Makarov, Tretiak, and Fetisov. Then came Fedorov, Bure, and Mogilny. Now, talents like Ovechkin, Malkin, Mozyakin, and Morozov grace the ice. After such consistency, hopes are extremely high for the next generation of Russian players. Perhaps some of the new upcoming players will choose to remain in Russia and play for the home crowd now that the reasons to leave the country for freedom and money aren’t so prevalent. The KHL represents an alternative to going abroad not only because its prestige is on the rise, but also because a majority of the teams can afford to pay players a salary comparable to that which they would receive in the NHL. But no matter where they choose to play, one thing remains certain: in the world of hockey, the Russians are here to stay.