In the wake of the 1990’s, the future of nascent post-Soviet Russia was in the hands of four groups of reformers, who were entrusted with applying a medicine known as “shock therapy” to a collapsing patient. These “doctors” were independent foreign advisers, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the US government, and, most importantly, President Yeltsin’s administration (Aslund 2007a, 2007b). Only the fourth was an internal group; the other three were external to the country. All four groups were, for the most part, committed to shock therapy. While no one was more invested in the cause than Yeltsin’s administration, the West, with its accumulated capital and experience, could have played a decisive role – but it did not. This essay examines the role of each “doctor” in detail and argues that help from the West was minimal, while Yeltsin’s administration was too politically polarized and weak to successfully implement the policies of shock therapy. As a result, shock therapy failed to achieve its fundamental goals in Russia.

Shock Therapists vs. Gradualists

To understand how the doctors attempted to assist Russia, we must first understand the theoretical model from which they operated. The term “Shock Therapy” was an invention of the media and a modification of Milton Friedman’s phrase “Shock Policy.” Jeffrey Sachs (2000), a professor of economics at Harvard, argues that Ludwig Erhard’s quick liberalization of price controls and government spending cuts in 1947-48 West Germany served as an inspiration for the shock therapy model.[1] Yet shock therapy, as it is now known, was first pioneered in Chile in 1975 by the “Chicago Boys”[2] following Augusto Pinochet’s coup and then in Bolivia in 1985 under Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada. Soon after, Eastern European countries followed suit: Poland in 1990, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria in 1991, Russia, Albania, and Estonia in 1992, and finally Latvia in 1993 (Marangos 2004). ..

Shock therapy is often associated with John Williamson’s Washington Consensus, a list of generally accepted economic policies for developing countries (Williamson 1990).[3] This list reads as follows:

- Fiscal discipline is needed.

- Among public expenditures, discretionary subsidies should be minimized, and education, health, and public investment should be priorities.

- The tax base should be broad, and marginal tax rates ought to be moderate.

- Interest rates should be market-determined and real interest rates positive.

- Exchange rates should be competitive.

- Foreign trade policy should be rather liberal.

- Foreign direct investment is beneficial but not a high priority.

- Privatization is beneficial because private industry is managed more efficiently than state enterprises.

- Deregulation is a useful means to promote competition.

- Property rights need to be made secure.

Shock therapy, according to the IMF, consisted of three radical, contractionary structural adjustment policies: liberalization; financial stabilization; and privatization. The original, slower and less radical shock therapy of Latin American countries differed from how shock therapy was applied in Russia. Sachs (2012) asserted that in Russia, large and rapid privatization rooted in neoliberalism led to “the dismantling of all government intervention to establish a supposedly free-market.”

Across all four groups of “doctors,” there were shock therapists and gradualists. Both shock therapists and gradualists argued for similar market reforms. Shock therapists, however, were more radical in their approach, arguing for drastic neoliberal economic changes made very quickly while the gradualists emphasized the need to build institutions as well as market and legal traditions.

Those advocating shock therapy tended to stress that quickness was the only way to prevent entrenched factions from taking advantage of the situation. They also had a general confidence that once market forces were introduced, institutions would reform or emerge to meet the new conditions. Iwasaki and Suzuki (2014) subdivide the shock therapists into “universal radicalism” and “conditional radicalism.” The former, represented by Murphy et al. (1992), de Melo et al. (1996), and Aslund (2007a), claimed that radical shock therapy ought to be applied universally to all post-Soviet countries. The latter was represented by Klaus (1993) and others who believed that shock therapy is preferable over gradualism as long as certain conditions are met (e.g. the government has the capacity to implement reforms and its citizens are open to capitalism).

Iwasaki and Suzuki (2014) subdivide the gradualist camp into four groups: “slow-paced gradualism,” “step-by-step gradualism,” “institutional gradualism,” and “eclectic gradualism.”[4] The first group, arguing for slower-paced reforms to minimize heavy socioeconomic costs such as high unemployment, prolonged recession, and decline in GDP, is represented by Murrell (1992), and King (2002). The second group, emphasizing the importance of sequencing gradual reforms in a step-by-step fashion, is represented by Van Brabant (1993), and Lian and Wei (1998). The third group, seeking to establish or reform institutions as a precondition to liberalization and privatization, is represented by Hecht (1994), Liew (1995), and Popov (2000). The fourth group, which believes that slow-paced and step-by-step gradualism are equally important, is represented by Dewatripont and Roland (1992), North (1994), Stiglitz (1999) and Arrow (2000). Nobel Laureate Douglass C. North, from the fourth group, expressed skepticism about radical reforms when he stated:

[Radical reform] is simply an inappropriate tool to analyze and prescribe policies that will induce development. While the rules may be changed overnight, the informal norms usually change only gradually… transferring the formal political and economic rules of successful Western market economies to third-world and Eastern European economies is not a sufficient condition for good economic performance (quoted in Aslund 2007: 50).

Therefore, the primary task, the gradualists maintained, was creating institutional infrastructure for a market economy while leaving privatization as a secondary task (Stiglitz 2002).

Some shock therapists argued for radical reforms but also for longer timelines to achieve results. The independent external adviser Jeffrey Sachs (1994: 274) stated that: “[i]f financial stabilization can be accomplished in the first year of radical reforms, and systemic transformation in the first five years, the structural change in the economy is a task of one to two decades.”

The general consensus among advocates of shock therapy was that the model’s ultimate economic goals were “the stimulation of economic activity, the modernization of the structure of industry, competitiveness on world markets, rising living standards, a stable and convertible currency, and budgetary stability” (Sakwa 2008: 311). Among the competing ideas and timelines to achieve these goals, President Yeltsin and his team of reformers opted for a more radical plan and timeframe. At the core of these reforms was a massive and hastily organized plan to privatize enterprises and property. Timelines were also radical; Yeltsin felt that reforms would be complete in six to eight months, though Yegor Gaidar, who initiated the reforms as First Deputy Prime Minister, set three years as his timeframe (Suny 1998; Sakwa 2008; McFaul 2001).[5] Although the radicals won in terms of having their ideas implemented, in the end, the fears of the gradualists were realized and structural change in Russia faltered.

As we shall see later, many factors played into this, including both political and economic. One major impediment, though, was the rise of Russia’s oligarchic class. More radical shock therapists equated these oligarchs to 19th century American barons like the Harrimans and Rockefellers; but Stiglitz (2002: 160), a gradualist, dismissed the comparison, stating that while American barons enriched themselves, they still created wealth for the country, Russian oligarchs, on the other hand, exploited Russian assets and left the country poorer.

The radicals have been more forgiving in their historical analysis. Aslund (2011) assessed in hindsight that in Russia, “[m]arket economic reforms have been highly successful, whereas democratization has been only partially auspicious, and the introduction of the rule of law even less so.” However, the shock therapists also found evidence of the success of their policies in areas outside of Russia, particularly in the Baltic States and Poland, which only intensified the debate as to the effectiveness of the shock therapy model. Five years into shock therapy in post-Soviet Eastern Europe, Sachs (1994) assessed that countries with the most radical reforms went furthest in restoring stability and laying the foundations for better standards of living. [6]

How Well Does Shock Therapy Work?

Given the highly differing results that shock therapy has had in various countries, arguments on the effectiveness of the theory in practice have been heated. Popov (2000) brought a fresh perspective to the dichotomous debate, contending that it was wrongly focused on speed, since Gorbachev’s 1985-91 gradualist reforms (which had tried to inject more moderate free market reforms under a four-year plan) and Yeltsin’s more radical reforms in 1991-92 both failed due to weak institutions, not speed. In addition, he presented the examples of Vietnam and China as two countries that shared many similar initial conditions but achieved economic growth without an extended recession while adopting two very different strategies: Vietnam pursued shock therapy while China chose a gradualist path. Conversely, Poland and Russia both undertook more radical shock therapy programs but ended with very different outcomes.

To illustrate the different paths taken under their specific shock therapies, Figure 1 below compares six countries for five years prior to and five years after their reforms. All except China adopted forms of shock therapy. Latin American countries, such as Bolivia and Chile, adopted a softer form of shock therapy while Russia adopted the most radical shock therapy through large-scale privatization. Other countries fall somewhere in between. Given the different historical legacies and the varying levels of economic development, some of these comparisons may be unmerited (see Figure 2). Russia, for instance, was by far the largest, most industrialized economy; yet, Russia lags behind from start to finish. The closest comparison to Russia is Poland, which still differed from Russia in that it historically had stronger institutions and a general consensus amongst its population to pursue market reforms (Aslund 2007a, 2007b).

Reform efforts cause different effects in each country. Chile, Poland, and Bolivia show sudden dips just after shock therapy followed by sustained growth. China does not have a dip, as it did not undergo shock therapy. In fact, China’s reform policies of 1978 spur it to its strongest growth year, although it did experience a dip just after that. Vietnam is a curious case in that it suffers the least in the year it implemented reforms. Poland experiences a later dip while Russia experiences a double dip.

Figure 1 Each timeline maps economic growth for five years prior to and after economic reforms. This timeline for Russia is from 1987-97; for Poland, it is 1984-94; for Vietnam, 1981-91; for Chile, 1970-1980; for Bolivia, 1980-1990; and for China, 1973-83. China pursued a gradualist approach while all other countries pursued a shock therapy approach. The date listed after each country’s name is the date when the reforms were implemented. Source: Retrieved from the USDA 2013; data from the World Bank World Development Indicators and the International Financial Statistics of the IMF.

Figure 2 Level of economic development and size of economy (Russian GDP here does not include other former Soviet states) has been largely heterogeneous for these comparison groups. This is a common argument among Russian scholars who contend that Chinese and Russian reforms are an inappropriate comparison, since Russia had already been industrialized at the time of shock therapy, while China started from agricultural reforms.

Figure 3 UNStats 2014. FSU stands for Former Soviet Union. Russia’s GDP performance compared to other former Soviet Union countries from 1990 to 2014.

While many explanations for these trends could be made, Popov (2000) emphasized that the reforms differed vastly in outcomes according to the incumbent political regimes and where the funding for reforms came from—i.e. whether funds ultimately came from diverting money from “ordinary government” (i.e. social programs and infrastructure), or from taking money from military budgets and government subsidies (i.e. from organs of power). He writes that,

- Under strong authoritarian regimes such as China, government spending cuts occur at the expense of military spending, subsidies and government investments but expenditure for “ordinary government” as a percentage of GDP remains largely unchanged (Naughton 1997).

- Under strong democratic regimes such as Poland, expenditure for “ordinary government” declined only in the pre-transition period but increased during transition.

- Under weak democratic regimes such as Russia, however, reduced government spending led to decline in military spending, subsidies and investment as well as expenditures for “ordinary government.”

Thus, we see that the success of shock therapy is correlated with the government’s strength to focus on the wellbeing of the populace rather than the maintenance of traditional power organs. To accomplish this, the governing structures would have to be powerful in relation to those interests.

Studies by USAID, for example, agree that political stability and the rule of law are decisive to the success of transitions (USAID and MSI 2002). Political stability and the rule of law can be achieved by either strong democracies or strong authoritarian regimes but not by weak democracies or weak authoritarian regimes. Political consensus can be established in strong democracies and can be bypassed in strong authoritarian regimes. Such was the case for Stalin, who, in a strong authoritarian regime, implemented his economic reforms and mercilessly crushed any opposition. Such was also the case in Chile under the autocrat Pinochet, whose shock therapy was implemented quickly and comprehensively. Such was also the case in authoritarian China, where gradual reforms were implemented gradually and comprehensively under the strong centralized control of the Chinese Communist Party. Poland’s shock therapy succeeded largely because of a democratic political consensus on working towards joining the European Union, maintaining social wellbeing, and building domestic institutions (Mueller 2007; Popov 2000; Murrell 1993). In contrast, economic reforms have proven more tenuous in politically polarized, weak democracies like Russia (Frye 2010).

Overall, shock therapy has now lost the support it once enjoyed with international organizations in the 1980s and 1990s. Nevertheless, shock therapy continues to surface in debates concerning how to radically transform political economies. For example, in the midst of unrest in Ukraine following the Crimean invasion, Leszek Balcerowicz, a Polish economist who administered shock therapy in Poland, recommended that Ukraine implement shock therapy (Philips 2014).

Russia: the Politics that Undermined the Economics

Frye (2010: 3) argues that Yeltsin’s administration, a highly polarized, weak democracy, was destined for slower and less consistent reforms. Having come from an academic career, Gaidar, the chief reformist, lacked political experience to maneuver through these bureaucracies. Furthermore, the central government was not in control of large swaths of society and the economy, including, for instance, the military-industrial complex. This meant that consistent reforms were impossible and the effort was doomed to failure (Popov 2000; Dabrowski 1993).

Economic policies are almost always highly dependent on the political environment and the strength of its decision-makers. Despite facing myriad hard-pressing problems, the “doctors” should have first put the hospital in order, so to speak. Yeltsin reflected in his memoir about the constitutional crisis of 1993 and his policies:

Maybe I was in fact mistaken in choosing an attack on the economic front as the chief direction, leaving government reorganization to perpetual compromises and political games. I did not disperse the Congress. . . . Out of inertia, I continued to perceive the Supreme Soviet as a legislative body that was developing the legal basis for reform. I did not note that the very Congress was being co-opted… but the painful measures proposed by Gaidar, as I saw it, required calm—not new social upheavals. Meanwhile, without political backup, Gaidar’s reforms were left hanging in midair. (1994: 127)

Yeltsin mistakenly assumed that dissolving the Soviet Union and achieving the independence of Russia was sufficient to generate political consensus and stability. Of course he understood that Russian democracy would be a work in progress, but he did not expect it to be as constrained by a weak government as was Gorbachev’s.

Even shock therapists admitted to failures in democratic consolidation. Yeltsin, following the 1993 constitutional crisis, rolled back democracy by forcing a super-presidential system.[7] While it was true that before the constitutional crisis there was a “dual state,” there was also an imperfect, informal democratic balance of power. However, Yeltsin’s super-presidential system served as a catalyst to an eventual rise to Vladimir Putin’s more centralized power structure. Most scholars who supported shock thereby agree that, in the end, this is what undermined Russia’s democratic consolidation. (Aslund 2007b).

There were other blows to the development of Russian democracy as well. Rose-Ackerman (1999), for example, observed that while elections increased the accountability of politicians, they also generated new incentives for corruption as political financing needs increased. Another blow came from declining popular support for the government when the government’s social programs declined. The loans-for-shares program had been designed by bankers to allow assets to move to the hands of private banks via loans provided by the banks. However, the loans generally failed because early tranches and assets never returned to the government – meaning that the banks and their owners retained ownership after having only given the government very small payments. This program designed by bankers and ultimately profitable only for a few private bankers, proved to be unpopular and ultimately unprofitable for the government, impeding its ability to maintain “ordinary government” expenditures. The loans-for-shares program proved to be unpopular and ultimately unprofitable for the government, impeding its ability to maintain “ordinary government” expenditures. In reality, these social programs had a political motivation that was less for the people as much as for strengthening the Yeltsin’s administration. Gaidar (2000) recalled “[t]he deals concerning the loans-for-shares were first and foremost directed at creating a critical mass of influential and powerful political forces, which were vitally interested in preventing the return of the Communist regime.”

However, the rapid privatization dealt still another blow to Russian state building by feeding corruption and reducing the effectiveness of Russia’s resources and industrial base in creating public wealth. Treisman (2000) observed that new democracies become significantly less corrupt only after about forty years as institutions become recognized and adhered to by society and other governing structures within the country. Russia’s democracy was more accurately O’Donell’s (1994) “Delegative Democracy”[8] or Zakaria’s (1997) “Illiberal Democracy.”[9] In other words, Russia, in the 1990s, became a democracy more in name than in practice.

The Doctors

- Doctor #1: External Advisers

There were several key independent external advisers, all of whom cooperated with other institutions seeking to influence Russia’s reforms. For example, Wedel (1998) referred to four high profile economic advisers: Jeffrey Sachs, Andrei Shleifer, Lawrence Summers, and David Lipton together as the “Harvard Boys,” as all four economists were from Harvard and worked closely together. In addition, Summers worked at the World Bank (1991-1993) and later in the US Treasury Department (1995-2001). David Lipton, who was Sachs’ protégé, also worked in the US Treasury Department (1993-1998).[10] Such connections existed for most if not all of the advisers, and because of this, the influence that they wielded tended to be tied to organizations they simultaneously represented. Three advisers who do deserve special mention, however, are Andrei Shleifer, Jeffrey Sachs, and Joseph Stiglitz.

Andrei Shleifer, a Russian-born Harvard professor of economics and the Russia project director of the Harvard Institute for International Development (HIID), advised Chubais from 1992 to 1997. It was at HIID that the idea of voucher privatization was first introduced (Aslund 2007b), and Shleifer went on to work closely with Chubais in the loans-for-shares privatization program that permanently transformed property relations in the country. HIID administered early funds from the US government: $57.7 million awarded by USAID and $350 million that President George H. W. Bush earmarked for America’s “Freedom of Russia and the Emerging Eurasian Democracies and Open Market Support Act” (McClintick 2005; Wedel 2001). Shleifer, among others, was instrumental in promoting the view that the government needed to be pushed out of the economy as quickly and as comprehensively as possible. As one of Anatoly Chubais’ primary advisers, he helped to write a publication called Privatizing Russia in 1995, which states:

At least in Russia, political influence over economic life was the fundamental cause of economic inefficiency, and that the principal objective of reform was, therefore, to depoliticize economic life. Price liberalization fosters depoliticization because it deprives politicians of the opportunity to allocate goods. Privatization fosters depoliticization because it robs politicians of control over firms.

Shleifer also helped tarnish the legacy of Western-led reforms by secretly investing in Russian securities while leading the project, in violation of HIID and US government conflict-of-interest rules (Sachs 2012). When the US government found out, it sued Harvard University. In 2005, a settlement was reached with Harvard paying $26.5 million in fines and Shleifer paying $2 million (McClintick 2005). The fraud likely made the US government more reluctant to listen to external advisers and more skeptical about assistance.

Another of the “Harvard Boys,” Jeffrey Sachs, a professor of economics at Harvard, served as an adviser from 1991 to 1994. Sachs (2012) personally considered his role minimal, for example, because he advised Gaidar, who was dismissed 13 months into shock therapy. However, he remained an adviser to the Russian government until 1994 and also became HIID’s director between 1995 and 1999 (Nelson and Kuzes 1994; McClintick 2005).

Sachs is correct, however, in that much of his advice was not heeded. Sachs (2012) argued for liberalization and privatization but also put a greater emphasis on safety nets, allowed for more state ownership of natural resource companies, and pushed for more foreign assistance. He considered that only two recommendations – price liberalization and commercialization of enterprises – out of his seven were achieved in Russia. All seven recommendations were as follows (Sachs 2012):

- Immediate price liberalization

- Immediate tightening of money supply and subsidies to firms

- Strong safety nets (e.g. the health care system)

- Large-scale and timely foreign assistance

- Commercialization of its enterprises by turning them into corporations with state ownership

- Privatization quick but transparent and law-based

- Large natural resource companies remain in state hands to ensure the Russian government received revenue.

Sachs was especially outspoken about the necessity of large-scale and timely foreign assistance for creation of preconditions for growth and democratic consolidation. Graham Allison of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and Grigory Yavlinsky, designed a large-scale infusion of Western financial and technical assistance known as the “Grand Bargain.” They estimated that Western aid consisting of grants and highly concessional loans ought to be around $30 billion per year over five years or $150 billion in total (Sachs 2012). Russia received only $22.7 billion total in IMF funds over the course of seven years (IMF 2014).

Another important adviser was Joseph Stiglitz: he served in the Clinton Administration’s Council of Economic Advisers between 1992 and 1997. He served at the World Bank as the Chief Economist between 1997 and 2000, where he became an outspoken critic of the IMF and the US Treasury Department.

Stiglitz (2002) advocated gradualist reforms and did not see the government as the problem, but as a crucial part of the solution. As much as he supported many of the shock therapy policies, he claimed that without sequencing reforms and building proper institutions first, economic policies would falter; and as the first two pillars of shock therapy (liberalization and stabilization) failed, they created obstacles for the third (privatization). Unlike Sachs, he maintained that Russia was a resource-rich country that could pull itself out of trouble independently and that, if it did not, no amount of loans would save it. The deterrent, of course, was corruption and Stiglitz did not deem it wise to provide loans to a country that had no institutional capacity to transparently and wisely allocate these loans. For example, over the span of the 1992-1999 IMF lending program, capital flight amounted to at least $45-50 billion each year between 1992 and 1998 (Sakwa 2008; Odling-Smee 2004), vastly overshadowing the IMF’s $22.7 billion contribution. As much as 30 percent of that capital flight occurred illegally. Critics charged Western investors and oligarchs with complicity and money laundering (Bishara 2012; Bedirhanoğlu 2004). Stiglitz assessed the outcomes as follows:

The radical reformers in Russia were trying simultaneously for a revolution in the economic regime and in the structure of society. The saddest commentary is that, in the end, they failed in both: a market economy in which many old party appartachiks had simply been vested with enhanced powers to run and profit from the enterprises they formerly managed, in which former KGB officials still held the levers of power. There was one new dimension: a few new oligarchs, able, and willing to exert immense political and economic power (2002: 163).

In some sense, no Westerner was as outspokenly critical of the West’s actions as he was. Stiglitiz (2002) openly criticized the US Treasury and the IMF for giving unconditional support to Yeltsin and Chubais. He contended that the West’s long term interests would have been better served by providing broad-based support to democratic processes by supporting young and emerging leaders throughout Russia. However, as described here, external independent advisers had minimal influence in Russia as individuals, with the possible exception of Shleifer (Sachs 2012; Wedel 2001).

- Doctor #2: The International Monetary Fund

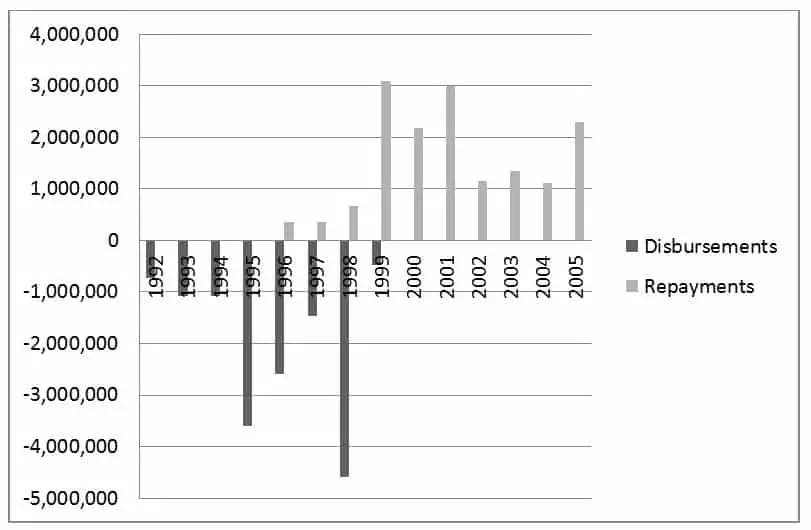

In the end, Russia received a surprisingly small amount of foreign aid. Between 1992 and 1999, the country received a total of $22.7 billion in IMF funds (IMF 2014). By contrast, Ukraine, after its pro-Western 2014 revolution, was promised $17.5 billion, to be delivered over four years (IMF 2015a). If to measure things in constant terms, 22.7 billion in 1999 would be about the equivelint of 32.2 billion in 2014. However, Ukraine’s economy in 2014 was seven times smaller than the Russian economy of 1992. As another example, Poland, whose population and economy were far smaller than Russia’s, received $42.3 billion during its transition period (Sozialistische Zeitung 2010).

In a self-assessment, the IMF concluded that its influence over Russia’s reforms was modest, stating that it had limited impact on overall fiscal policy and major structural reforms, but had, in its estimation, a positive impact on monetary policy (Odling-Smee 2004). The IMF had advocated longer-term structural and institutional reforms in terms of fiscal policy (Onis and Fikret 2005). In terms of monetary policy, the IMFs recommendations to support exchange rates and target inflation had actually been problematic.

The IMF’s monetary policy recommendations encouraged Russia to artificially support its currency. A substantial portion of IMF funds provided to Russia ($11.2 billion, about half of all funds given) were provided with the stipulation that they be used for this. In addition, the World Bank loaned Russia $6 billion and the Japanese government loaned $5.4 billion for currency support (Stiglitz 2002: 48).

The rationale was to contain inflation: a weakening currency could encourage exports, driving up prices at home by driving down supply, and would make imported goods more expensive. However, the currency was already overvalued, and the artificially strong currency led to a flood of imported goods. Domestic production lost its competitiveness. In six years, Russia’s productive capacity declined by 40 percent, a loss of capacity greater than what has occurred in many wars (see Figure 4, below). It would take another eight years for Russian GDP to recover to pre-1989 levels (Stiglitz 2002).

Poland, which is counted as one of shock therapy’s successes, actually ignored the IMF’s advice to curb inflation and left it at around 20 percent throughout its reform years (Stiglitz 2002: 156). Meanwhile, countries like the Czech Republic that had adhered most closely to IMF policies by reducing inflation to a target of two percent suffered economic stagnation.Also, despite the IMF’s self-appraisal, the organization did in fact have a substantial impact on fiscal policy in that its recommendations for Russia to take out foreign loans for deficit financing were enacted. As a result, debt rose from $65.3 billion in 1991 to $110 billion by 1997 (Sakwa 2004). This increased debt was not enough to fuel growth because of the collapse in production caused by Russia’s artificially supported ruble. Only after an inevitable devaluation, following the 1998 crisis, did import substitution begin as domestic industries finally became more competitive against imports and production began to rise again. Targeting inflation, which the IMF considered to be one of its positive effects on monetary reform, had in fact been harmful. Inflation is very often a natural phenomenon that comes with GDP growth. As seen in the Russian case, beating down inflation to unnecessarily low levels can actually hinder economic growth as high interest rates stifle new investment.

- Doctor #3: The United States

The Soviet Union was a threat like no other to the United States. The Soviets were not only a nuclear superpower but presented an alternative political and economic system. The Soviets openly and globally spread a communist ideology that was both anti-Western and anti-capitalist (Gorbachev 2000). The United States, of course, reciprocated this enmity toward the Soviet Union. During World War II, then-senator of Missouri, Harry S. Truman stated, “If we see that Germany is winning the war, we ought to help Russia, and if Russia is winning we ought to help Germany and that way let them kill as many as possible” (Sakwa 2008: 341). Richard Pipes, who had advised the US government on ways to damage the Nazi economy during World War II, advised the US on how to use similar tactics of economic policy to cripple the Soviet economy during the Cold War (Gaidar 2010).[12] However, even Pipes confessed that the Soviet dissolution was unexpected (Aron 2011).

In the late 1980s when the Soviet collapse became an imminent possibility, the West actually tried to preserve the Soviet Union, fearing nuclear proliferation and political instability in the region (Sakwa 2008). Even when Yeltsin, the “Westernizer” as the Russian media referred to him, was ascending in power, the West was skeptical of the iconoclast and preferred to deal with Gorbachev, who was a committed Leninist (Rosenthal 1991). The Bush administration supported Gorbachev until October 1991 and only belatedly and reluctantly switched its allegiance to Yeltsin (Dunlop 1993).

The US provided economic consultants to Russia through the US Treasury, led by Larry Summers and David Lipton (Rutland and Dubinsky 2008). They maintained that creating a market economy in Russia should be carried out first, with political reforms pursued only afterwards (Aslund 2007a; Boycko, Shleifer and Vishny 1995: 65).

Economic assistance arrived but was insufficient. By 2001 (almost 10 years after the start of reforms), the US had sent only about $1 billion in aid, and like IMF funds, much of it was earmarked for specific projects favored by the US that were not necessarily the most effective in restoring Russia’s economy or infrastructure. Two-thirds of the billion dollars were spent on nuclear-weapon related programs, managed by the Pentagon and the Department of Energy (Rutland and Dubinsky 2008).[13] Thus, despite profuse academic literature demonstrating that foreign assistance was correlated with economic growth, the aid provided by the US was insufficient (Easterly 2003; Dalgaard, Hansen and Tarp 2004).

The US also could have committed more strongly to Russian reforms. In post-war Europe, the Marshall Plan was widely lauded as successful (De Long & Eichengreen 1991); however, the financial assistance given Russia lacked the structure and generosity of the Marshall Plan. The Marshall Plan was highly-structured and designed to ensure that European countries regained their strengths (of course, with some restraints on German military force). The US funded the effort with $13 billion in aid (equal to about $128 billion in 2014 dollars) to Western Europe between 1948 to 1951 (De Long and Eichengreen 1991; “The Marshall Plan”). Aid given to Russia was given without an overall plan. The Marshall plan was hardly an impartial or altruistic effort on the part of the US. It was specifically designed to rebuild the economies of war-ravaged Europe to stop the spread of communism. That is, it was designed to serve major US political interests on a wide scale. In contrast, US efforts to assist Russia were directed at narrow policy goals: keeping Yeltsin in office and keeping nuclear weapons secured. Just enough was given to maintain these specific interests – but not enough to help rebuild the economy and to ensure democracy could prosper. Indeed, Condoleezza Rice (2000) specifically recounted that keeping Yeltsin in power and disarming Russia was of primary interest, while building democracy and market economy were far secondary. Later, Aslund (2011) referred to this disregard as a “sin of omission.”

Admittedly, post-World War II Europe was in a qualitatively different condition than post-Soviet Russia. The former needed resources to rebuild institutions and economies that had been destroyed by war. The latter needed resources and guidance to replace old command institutions with new market institutions. However, the United States, which had extensive experience with external assistance in helping Germany, Italy, and Japan restructure themselves into modern democracies with strong market economies, chose not to commit (Payne 2006) to assisting its former enemy Russia on the same level.

There was an obvious conflict of interest in that political interests in the US saw no interest advantage in reviving what they saw as an arch-nemesis. Further, Russia, unlike Germany or Japan after the Second World War, was never willing to trade its foreign policy autonomy, for prosperity and security within an increasingly integrated community of nations whose priorities were economic rather than political (Mankoff 2009).[14]

Nevertheless, the West’s assistance, though insufficient, served to at least partially alleviate the turmoil in Russia. For example, after the financial crash of 1998, the US and EU announced food aid packages valued at over $1.5 billion for the Russian Federation (US contribution totaled $409 million; by comparison, US food aid to the continent of Africa in FY 2000 was $342.4 million) (Sedik, Sotnikov and Wiesmann 2003).

The US’s largest contribution to aid to Russia was the Clinton administration’s role in pressuring the IMF and the World Bank, which were unwilling at first to provide loans to country that they saw as corrupt (Stiglitz 2002). Condoleezza Rice (2000) recalled that due to the coinciding political interest of preserving Russia from communist retrenchment, US support for democracy and shock therapy in Russia soon became synonymous with unconditional support for the Western-friendly Yeltsin and his agenda, despite growing awareness that his reforms were increasingly ineffective. Yeltsin received consistent support from the leaders of the Western democracies (Bill Clinton, Helmut Kohl, Francois Mitterand), which eventually contributed to the rise of a disgruntled and hardline Russian parliament (Dunlop 1993).

- Doctor #4: The Russian Federation

The biggest blow to reforms was the Russian government’s lack of political consensus and control over its own country. Yeltsin either had to win the hearts of competing factions or defeat them to maintain power and govern the country. These factions included the powerful military-industrial complex, large energy companies, the remnants of the KGB (the USSR’s state security department) and regional governments, all of which had differing and often competing interests (Dunlop 1993; Mankoff 2009).

The greatest threat, however, lay in the fact that Yeltsin’s Russia was essentially a “dual state” with the president and the parliament sharing vested powers (Sakwa 2010). Russia, in the first years of its independence from the USSR, was still operating under a constitution adopted under communism in 1978. That constitution did not effectively sustain Russia’s new democracy because it did not clearly delineate the boundaries of the president’s and parliament’s authority. The power struggle culminated in the constitutional crisis of 1993 that nearly escalated to a civil war (Dunlop 1993; Sakwa 2010). Yeltsin, in his autobiography, complained that he did not possess the levers to pull to effectively enact his planned reforms (Yeltsin 1994). In other words, Russia’s most pressing need was for political rather than economic reform.

In November of 1991, Yeltsin appointed Yegor Gaidar, a young reform-minded economist, as deputy prime minister in charge of spearheading shock therapy.[15] Yeltsin’s decision was hardly surprising because Gaidar and Yeltsin held shared beliefs in radical reforms, in contrast to Gorbachev’s beliefs in gradual reforms. Although he had no background in politics,[16] Gaidar was by far the most qualified young economist in the Soviet Union, with a good understanding of market economies. Furthermore, his reforms were endorsed by the IMF, the US Treasury and Western advisers, who promised assistance as long as Russia met certain conditions (Serge 1992). Together with his team of 35- to 40-year-old bright reformers who had worked with Gaidar in the Institute of Economic Policy, as well as external advisers, Gaidar worked tirelessly to apply shock therapy until his dismissal. Today, he is considered the father of Russia’s modern market economy.[17]

Yeltsin, however, underestimated what his opponents could do. Although the peaceful dissolution of the USSR minimized the loss of lives, it also allowed opponents to coalesce against him. Among these opponents, the two most influential individuals were Vice President Aleksandr Rutskoi and Ruslan Khasbulatov, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation. They disagreed with Yeltsin on two fronts. First, they disagreed with Gaidar’s shock therapy, preferring a state-controlled transition to a market economy (McFaul 2001). Their criticisms quickly garnered the support of the nomenklatura (political organizations and interest groups) that were privileged under the Soviet system and were wary of what changes to the system would do to their status. Second, Rutskoi and Khasbulatov disagreed with efforts to democratize Russia. In the very recent past, they argued, Gorbachev mistakenly experimented with democracy while pursuing economic reforms, and the result had been negative; Russia needed authoritarianism that would insulate the government from societal pressures until the market reforms were implemented (McFaul 2001).

With a strong opposition and weak government, Russia became practically ungovernable (Reddaway 1993). Russia was de jure a parliamentary republic, but de facto a presidential republic (Sakwa 2008). The balance of power between the executive and legislative branches was determined by a continual power struggle, rather than a clear delineation in the constitution. Increasingly, the parliament grew in strength and was able to block the executive branch’s initiatives for constitutional amendments and radical economic reforms. For example, under pressure from the parliament, Yeltsin was forced to dismiss his prime minister, Yegor Gaidar, and replace him with a conservative, Viktor Chernomyrdin. Much like Gorbachev, Yeltsin was unable to create a broad political and social support base. Yeltsin’s political reforms saw similar results to Gorbachev’s: polarization, confrontation, and eventually armed conflict (McFaul 2001). The Russian case seriously undermined Przeworski’s (1991) postulation that uncertainty coupled with equally strong parties creates a condition conducive to democracy; in Russia, competition bred conflicts instead. The lesson learned was that uncertain distributions of power were not guarantors of a successful transition.

The disagreements were both political and economic. While Yeltsin was determined to continue with the shock therapy, his parliament disagreed and impeached Yeltsin, proclaiming Vice President Alexander Rutskoi to be acting president. In fact, Yeltsin was temporarily abandoned by the heads of the Russian Defense Ministry, the Ministry of State Security, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, who sided with the parliament against him (Dunlop 1993).

Two constituencies proved decisive to Yeltsin’s eventual victory. Brian Taylor (2003), a political scientist, observed that in the constitutional crisis of September 1993, the armed forces moved to help Yeltsin. Rutskoi’s key blunder was ordering the army to storm Ostankino, the television station, and the Moscow mayor’s office. The army moved against peacefully demonstrating people (ibid.). With 87 people killed and 437 wounded, the clash marked the single-most deadly event of street fighting in Moscow’s history (Winters and Litovkin 2013).[18] Public support also fell behind Yeltsin according to a poll taken by the All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion (VTsIOM) on September 24-28, 1993, forty-four percent supported the president and the government, fifteen percent the Supreme Soviet, and thirty-two percent supported neither group, with nine percent unable to answer (Dunlop 1993).[19]

Conclusion

Shock therapy certainly succeeded in preventing Russia’s complete collapse and communist retrenchment. In place of communism, Russians could have erected fascist, imperialist, or neo-communist regimes, but they did not (McFaul 1999). Furthermore, despite heavy costs, the rudiments of a market economy were established through shock therapy. However, shock therapy ought to be assessed by its original promises: establishing the preconditions for economic growth and democratic consolidation (Aslund 2007; Stiglitz 2002; Sachs 2000; Friedman 2000). In this view, shock therapy in Russia failed due in part to insufficient and incompetent assistance by external groups but primarily due to a lack of internal political consensus and control.

Since then, Russia has made little progress on democratic consolidation. Yeltsin himself admitted in his resignation speech that his premature exit and appointment of his successor meant that Russia would not see a democratically elected leader transfer power to another as established in the constitution (Sakwa 2008).[20] The aforementioned problems persist to this day because Yeltsin’s established super-presidentialism and Putin’s consolidated power structure are not easily changed and bear long-lasting influences in politics. McFaul notes,

Pluralist institutions of interest intermediation are weak, mass-based interest groups are marginal, and institutions that could help to redress this imbalance – such as a strong parliament, a robust party system, and an independent judiciary – have not consolidated. In addition, a deeper attribute of democratic stability – a normative commitment to the democratic process by both the elite and society – is not apparent in Russia (McFaul 2001: 4)

Twenty years later, Russia is still plagued by structural economic problems: low labor productivity; poor infrastructure; excessive regulations; energy inefficiency; high public spending, especially on pensions; heavy dependence on commodities, especially oil and gas; and widespread corruption and weak rule of law (Åslund et al. 2010). The “two turnover” rule of electoral procedure – wherein two cycles of leadership must transition through competitive elections – which many scholars state is the key determinant for the consolidation of democracy, became indefinitely delayed with Putin’s rise to power continued rule of Russia (McFaul 2001). Thus, to this day, neither the economic nor political goals of shock therapy have been achieved in Russia.

Footnotes

[1] Balcerowicz (2000) considered the German case far simpler than the post-Soviet transition. While Germany had to restore suspended capitalism, the post-Soviet countries had to break down the command economy, with 90 percent state-ownership of enterprises, to create a market economy from the ground up. Nonetheless, West Germany was also a transitional reform that transformed the country from an authoritarian model to a post-war free market model.[2] The Chicago Boys were a group of Chilean economists in the 1970. Most were educated at the Department of Economics of the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger. Some were educated at by its affiliates in the Economics Department at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. [3] Aslund (2007: 32) stated of shock therapy that “[t]he radical reform program for post-communist countries followed the Washington Consensus closely, but it went further and was more specific. It is incorrect, as is often done, to equalize the two.” Actually, shock therapy preceded the Washington Consensus by almost half a century. Shock therapy was first introduced in 1975 in Latin America and evolved from there. The shock therapy applied in Russia was different and more radical than the Latin American example. It would be more proper to state that the Washington Consensus was rooted in the shock therapy doctrine. [4] Iwasaki and Suzuki (2014) is a review of research done during and after shock therapy. Therefore, some of the arguments made by authors referenced in this section may not have been present during the early 90’s. [5] Shock therapy as implemented in Russia was only partially Gaidar’s program, since his reforms were constantly disrupted. He began leading reforms as First Deputy Prime Minister from March 1992 but by June 1992, he was replaced by old-style industrialists, among them Viktor Chernomyrdin. Russia’s legislative body was opposed to both Yeltsin and Gaidar. (3 months) While Gaidar was promoted to as the acting Prime Minister between June 1992 and December 1992, his radical reform programs drew much criticism and grew increasingly unpopular. His short comeback as the First Deputy Prime Minister following the 1993 Crisis was also relatively inconsequential and short-lived from September 1993 until January 1994. The far more conservative Victor Chernomyrdin assumed the role of Deputy Prime Minister at the critical juncture between May 1992 and December 1992 and extended his influence over reforms as Prime Minister from December 1992 to March 1998. [6] In Sachs’ assessment, not only Poland but also the Czech Republic, Slovenia, and Estonia were a testament that radical reform is the right way to transition away from the Soviet economies. By contrast, he contended that countries that undertook gradualist reforms lagged behind. In the latter group, he includes Eastern countries like Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania and former Soviet countries like Uzbekistan and Belarus. [7] The need for separation of powers or checks and balances and many other crucial mechanisms were simply discarded which led to disproportionate power vested in the executive branch (McFaul 2001: 311). [8] “Whoever wins election to the presidency is thereby entitled to govern as he or she sees fit, constrained only by the hard facts of existing power relations and by a constitutionally limited term of office” (Rueschemeyer, Huber and Stephens 1992: 311). [9] “Democratically elected regimes, often ones that have been reelected or reaffirmed through referenda, are routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving their citizens of basic rights and freedoms” (Zakaria 1997). [10] David Lipton is now serving as the First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund as of September 1, 2011 <http://www.imf.org/external/np/omd/bios/dl.htm>. [11] IMF transactions are denominated in SDR – a basket of global currencies. The total transaction in the chart amounts to 15.6 billion SDRs which translated into roughly $22.6 billion USD between 1992 and 1999. [12] In 1982, Reagan passed a directive on national security (NSDT-66) that set damaging the Soviet economy as its goal (Gaidar 2010: 107). [13] The USAID program ceased its operation in 2012, but between 1999 and 2012, this assistance amounted to less than $200 million with a similar usage breakdown (20 Years of USAID Economic Growth Assistance in Europe and Eurasia 2013). [14] Perhaps, the only possible exception was Andrey Kozyrev, who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation between 1991 and 1996. He is widely considered the Atlantist whose policies were aimed at pivoting to the West, but his policies would grow highly unpopular in Russia (Mankoff 2009). [15] “Five teams were headed, respectively, by Grigory Yavlinsky (liberal but supported the maintenance of the Soviet Union), Yegor Gaidar (consistent market liberal and for Russia’s independence), Yevgeny Saburov (liberal but cautious), Yuri Skokov (illiberal), and Oleg Lobov (illiberal)” (McFaul 2001: 142; Aslund 2007: 90). [16] “Gaidar’s political position was always exceptionally weak. Appointed deputy prime minister in charge of economic policy on 7 November 1991, he became first deputy prime minister on 2 March 1992, acting prime minister on 15 June 1992, and was dismissed on 14 December 1992 (returning briefly to the economics portfolio in late 1993)” (Sakwa 2008: 292). [17] Even though, for the public, Gaidar’s name has become forever associated with disaster, many public servants and academics laud his efforts. Konstantin Sonin (2009), a prominent Russian economist, stated, “Gaidar proved to be correct: Two weeks after his price-liberalization policy went into effect, Russians once again saw food and basic consumer goods in the shops after years of being absent.” Anatoly Chubais, the Minister of Privatization in the early 1990s, stated, “It was Russia’s huge good fortune that in one of the worst moments in its history it had Yegor Gaidar. In the early 1990s he saved the country from famine, civil war and disintegration…” (Denisov 2009). [18] Non-governmental sources claim that the death toll was as high as 2,000. [19] In the city of Moscow, where the crisis was actually unfolding, fifty-seven percent supported Yeltsin, fifteen percent the Supreme Soviet, twenty-four percent supported neither, and four percent were unable to answer (Kuranty, 1 Oct 1993, 1 as cited in Dunlop 1993: 318). [20] Gorbachev described Putin’s governing party, United Russia, as “a bad copy of the Soviet Communist Party” (Levy 2010). In that sense, Gorbachev did a great service to Russia by not clinging to power or appointing a successor (Shevtsova 2011).

Bibliography

Aron, Leon. “Everything You Think You Know About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Is Wrong.” Foreign Policy 68 (2011).

Arrow, Kenneth J. “Economic Transition: Speed and Scope.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft (2000): 9–18. Print.

Aslund, Anders. How Capitalism was Built: The transformation of Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Aslund, Anders. “The U.S., Not Gaidar, Killed Yeltsin’s Reforms.” The Moscow Times, 24 Aug. 2011. Web. 09 June 2014. <http://www.themoscowtimes.com/opinion/article/the-us-not-gaidar-killed-yeltsins-reforms/442563.html>.

Aslund, Anders. Russia’s Capitalist Revolution: Why market reform succeeded and democracy failed. Peterson Institute, 2007b.

Aslund, Anders, Sergej Maratovič Guriev, and Andrew C. Kuchins, eds. Russia After the Global Economic Crisis. <http://www.worldpublicopinion.org/pipa/articles/views_on_countriesregions_bt/451.php?lb=btvoc> Peterson Institute, 2010.

Balcerowicz, Leszek. “A Comparison of Polish and Russian Reform.” Interview. PBS, 12 Nov. 2000. Web. 20 May 2014. < http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/int_leszekbalcerowicz.html>.

Bedirhanoğlu, Pınar (2004) “The Nomenklatura’s Passive Revolution in Russia in the Neoliberal Era” in Leo McCann (ed.), Russian Transformations: Challenging the Global Narrative, RoutledgeCurzon, 19-41.

Bishara, Marwan. “Putin’s Russia.” Empire. Al Jazeera. Doha, Qatar, 30 Apr. 2012. Television.

Boycko, Maxim, et al. “Privatizing Russia.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (1993): 139-192.

Calcagno, Peter T., Frank Hefner, and Marius Dan. “Restructuring before Privatization—Putting the Cart before the Horse: A Case Study of the Steel Industry in Romania.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 9.1 (2006): 27–45. Print.

Dalgaard, Carl-Johan, Henrik Hansen, and Finn Tarp. “On the Empirics of Foreign Aid and Growth.” The Economic Journal 114.496 (2004): 191-216.

De Long, J. Bradford, and Barry Eichengreen. The Marshall Plan: history’s most successful structural adjustment program. No. w3899. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1991.

De Melo, Martha, Cevdet Denizer, and Alan Gelb. “Patterns of Transition from Plan to Market.” The World Bank Economic Review 10.3 (1996): 397–424. Print.

Dewatripont, Mathias, and Gerard Roland. “The Virtues of Gradualism and Legitimacy in the Transition to a Market Economy.” The Economic Journal 102.411 (1992): 291–300. Print.

Dunlop, John B. The rise of Russia and the fall of the Soviet empire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Easterly, William. “Can foreign aid buy growth?” Journal of Economic Perspectives (2003): 23-48.

Friedman, Milton. “On His Role in Chile Under Pinochet.” Interview. PBS, 1 Oct. 2000. Web. 20 May 2014. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitextlo/int_miltonfriedman.html>.

Frye, Timothy. Building states and markets after communism: the perils of polarized democracy. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Gaidar, Yegor. Collapse of an empire: lessons for modern Russia. Brookings Institution Press, 2010.

Gaidar, Yegor. “What Russia Learned from the Polish Experience.” Interview. PBS, 5 Oct. 2000. Web. 20 May 2014. < http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitextlo/int_yegorgaidar.html>.

George C Marshall Foundation, The “The Marshall Plan.” The Marshall Plan. George C Marshall Foundation, n.d. Web. 26 May 2014. <http://www.marshallfoundation.org/TheMarshallPlan.htm>.

Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich. On My Country and the World. Columbia University Press, 2000.

Hecht, James L. “Shocked Russians, chagrined economists.” Orbis 38.3 (1994): 499-504.

International Monetary Fund. “Russian Federation: Transactions with the IMF 1992-2014.”

International Monetary Fund. IMF COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT. IMF Executive Board Approves 4-Year US$17.5 Billion Extended Fund Facility for Ukraine, US$5 Billion for Immediate Disbursement. Press Release No. 15/107. N.p., 11 Mar. 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2016.

International Monetary Fund. IMF COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT.Statement by IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde on Ukraine.Press Release No. 15/50. N.p., 12 Feb. 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2016.

Iwasaki, Ichiro, and Taku Suzuki. “Radicalism versus Gradualism: A Systematic Review of the Transition Strategy Debate.” Hermes IR (2014).

King, Lawrence. “Postcommunist Divergence: A Comparative Analysis of the Transition to Capitalism in Poland and Russia.” Studies in Comparative International Development 37.3 (2002): 3–34. Print.

Kissinger, Henry A. “Dealing with a New Russia,” Newsweek, 2 Sept (1991).

Klaus, Vaclav. Interplay of Political and Economic Reform Measures in the Transformation of Postcommunist Countries. Heritage Foundation, 1993.

Kornai, Ya. Ekonomika defitsita [Deficit Economy] (Moscow: Ekonomika, 1990).

Lian, Peng, and S.-J. Wei. “To Shock or Not to Shock? Economics and Political Economy of Large-Scale Reforms.” Economics & Politics 10.2 (1998): 161–183. Print.

Liew, Leong H. “Gradualism in China’s Economic Reform and the Role for a Strong Central State.” Journal of Economic Issues 29.3 (1995): 883–895. Print.

Lipton, David, Jeffrey Sachs, and Lawrence H. Summers. “Privatization in Eastern Europe: the case of Poland.” Brookings papers on economic activity (1990): 293-341.

Management Systems International (MSI) and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Achievements in Building And Maintaining the Rule of Law. Washington, DC. (2002):118-122.

Mankoff, Jeffrey. Russian foreign policy: the return of great power politics. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009.

Marangos, John. “Was shock therapy consistent with democracy?” Review of Social Economy 62.2 (2004): 221-243.

McClintick, David. “How Harvard lost Russia.” Institutional Investor-International Edition- 30.12. 2005.

McFaul, Michael. “Getting Russia Right.” Foreign Policy. (1999): 58-73.

Mueller, Hannes. “Why Russia failed to follow Poland: Lessons for economists.” London: LSE, STICERD (2007).

Murrell, Peter. “What is Shock Therapy? What did it do in Poland and Russia?”Post-Soviet Affairs 9.2 1993: 111-140.

Murrell, Peter. “Evolutionary and Radical Approaches to Economic Reform.” Economics of Planning 25.1 (1992): 79–95. Print.

Naughton, Barry. 1997. “Economic Reform in China. Macroeconomic and Overall Performance,” In: The System Transformation of the Transition Economies: Europe, Asia and North Korea, Ed. by D. Lee. Yonsei University Press, Seoul.

Nelson, Lynn D., and Irina Y. Kuzes. Property to the people: the struggle for radical economic reform in Russia. ME Sharpe, 1994.

Noam Chomsky. “Superpower Confrontation: Fear and Reality in the Arms Race.” Interview by Tony Mullaney. Noam Chomsky “A Short History of the Cold War” (1985) JTJ Films, 4 Oct. 2013. Web. 29 May 2014. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVqmPQDaiYg>.

North, Douglass C. “Economic performance through time.” The American Economic Review 84.3 (1994): 359-368.

O’Donell, Guillermo A. “Delegative democracy.” Journal of democracy 5.1 (1994): 55-69.

Odling-Smee, John C. The IMF and Russia in the 1990s. International Monetary Fund, 2004.

Payne, James L. “Did the United States create democracy in Germany?” INDEPENDENT REVIEW-OAKLAND- 11.2 (2006).

Philips, Alan. “Shock Therapy Helped Poland, Can It Do the Same for Ukraine?” The National. Abu Dhabi Media, 5 June 2014. Web. 18 June 2014. <http://www.thenational.ae/thenationalconversation/comment/shock-therapy-helped-poland-can-it-do-the-same-for-ukraine#page1>.

Popov, Vladimir. “Shock Therapy versus Gradualism Reconsidered: Lessons from Transition Economies after 15 Years of Reforms.” Comparative Economic Studies 49.1 (2007): 1–31. Print.

Przeworski, Adam. Democracy and the market: Political and economic reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Reddaway, Peter. “Russia on the Brink?” Quadrant 37.4 (1993): 9.

Rice, Condoleezza. “Promoting the national interest.” Foreign Affairs. 79 (2000): 45.

Rose-Ackerman, Susan, “Political Corruption and Democracy” (1999). Faculty Scholarship Series. Paper 592. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/592

Rosenthal, Andrew. “Bush Reluctantly Concludes Gorbachev Tried to Cling to Power Too Long.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 24 Dec. 1991. Web. 28 May 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/1991/12/25/world/end-soviet-union-bush-reluctantly-concludes-gorbachev-tried-cling-power-too-long.html>.

Rueschemeyer, Dietrich, Evelyne Huber Stephens, and John D. Stephens. “Capitalist development and democracy.” Cambridge, UK (1992).

Rutland, Peter, and Gregory Dubinsky. “US–RUSSIAN RELATIONS: HOPES AND FEARS.” 2008.

Sachs, Jeffrey (1996) “Achieving Rapid Growth in the Transition Economies of Central Europe,” Harvard Institute for International Development, Development Discussion Paper no. 544.

Sachs, Jeffrey. “Russia’s Difficult Reform.” Interview. PBS, 51 Jun. 2000. Web. 22 May 2014. < http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/int_jeffreysachs.html#19>.

Sachs, Jeffery. “Shock Therapy in Poland: Perspectives of five years.” Tanner Lectures on Human Values 16 (1995): 265-290.

Sachs, Jeffery. “What I Did in Russia.” JeffSachs.org, 14 Mar. 2012. Web. 14 May 2014. <http://jeffsachs.org/2012/03/what-i-did-in-russia/>.

Sackur, Stephen. “Yegor Gaidar.” Hardtalk. BBC World. London, United Kingdom, 19 Feb. 2008. Web. 14 May 2014. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/player/nol/newsid_7250000/newsid_7253600/7253659.stm?bw=bb&mp=wm&asb=1&news=1&ms3=54&ms_javascript=true&bbcws=2>.

Sakwa, Richard. “The dual state in Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs 26.3 (2010): 185-206.

Sakwa, Richard. Russian Politics and Society. Routledge, 2008.

Schmemann, Serge. “Cabinet in Russia won’t step down.” The New York Times, 14 Apr. 1992. Web. 14 May 2014.

Sedik, David J., Sergey Sotnikov, and Doris Wiesmann. Food security in the Russian Federation. No. 153. Food & Agriculture Org., 2003. (http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5069e/y5069e03.htm#bm03)

Sonin, Konstantin. “The Death of Russia’s Premier Shock Therapist | Opinion.” Opinion. The Moscow Times, 18 Dec. 2009. Web. 14 May 2014. <http://www.themoscowtimes.com/opinion/article/the-death-of-russias-premier-shock-therapist/396363.html>.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and its Discontents. WW Norton & Company, 2002.

Stiglitz, Joseph. “Whither Reform.” Washington DC: The World Bank (1999). Web. 12 Feb. 2016.

Suny, Ronald G. The Soviet experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the successor states. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Taylor, Brian D. Politics and the Russian army: civil-military relations, 1689-2000. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Treisman, Daniel. “The causes of corruption: a cross-national study.” Journal of public economics 76.3 (2000): 399-457.

United States Economic Research Service, Department of Agriculture. Real Historical Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Growth Rates of GDP for Baseline Countries/Regions (in Billions of 2010 Dollars) 1969-2014. By Kari Heerman. N.p.: n.p., n.d. USDA. Web. 30 Dec. 2013.

US Aid. 20 Years of USAID Economic Growth Assistance in Europe and Eurasia. Rep. no. EEM-I-00-07-00001-00. Rockville: SEGURA Partners LLC, 2013. Web. 29 May 2014.

Van Brabant, Jozef M., et al. “Survey Article: Lessons from the Wholesale Transformations in the East.” Comparative Economic Studies 35.4 (1993): 73–102. Print.

Wedel, Janine R. Collision and Collusion: The strange case of Western aid to Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Williamson, John. “Speeches, Testimony, Papers: Did the Washington Consensus Fail?” Institute for International Economics (2002).

Winters, Estelle, and Nikolay Litovkin. “Russian Constitutional Crisis, 1993: Yeltsin Had No Choice but to Restore Peace – Expert.” Voice of Russia, 4 Oct. 2013. Web. 27 May 2014. <http://voiceofrussia.com/2013_10_04/Russian-constitutional-crisis-1993-Yeltsin-had-no-choice-but-to-restore-peace-expert-9838/>.

World Bank and Izdatelstvo Ves Mir. The Russian Labor Market: Moving from Crisis to Recovery. Washington, DC. 2003.

World Bank Staff. World Development Report 1996: From Plan to Market. Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1996.

Yeltsin, Boris. The Struggle for Russia. (Translated by Catherine A. Fitzpatrick). New York: Crown, 1994.

Zakaria, Fareed. “The rise of illiberal democracy.” Foreign Affairs (1997): 22-43.