During the First World War, Austria-Hungary extended its long-standing policy of fostering and co-opting nationalist movements to its prisoner-of-war (POW) camps. While it may seem paradoxical for a multiethnic empire to encourage nationalism among minority groups within one’s borders, the strategy had previously proven effective in securing domestic support from these groups. It was therefore logical to apply the same approach to POWs, with the hope of recruiting sympathizers or undermining morale within the Russian Empire.

This paper examines how Austria-Hungary used cultural programming and nationalist education in its POW camps—particularly at Feldbach and Freistadt—as part of a calculated propaganda campaign. Designed to show the empire as a humane, enlightened, and powerful, these activities were designed to promote national consciousness among minority prisoners from the Russian Empire, aimed to both strengthen Austria and destabilize Russia.

These case studies shed light on how multinational empires weaponized culture during wartime and offer a framework for understanding similar strategies in other multiethnic states.

Understanding Culture and Propaganda

“You may kill me, I’ll die, but I will not go to dig trenches against my own.”[1] This brave statement is credited to Cossack soldier Klyushin from Orenburg, a city near the Ural region of Russia, as being spoken in July 1915. Klyushin had been imprisoned in an Austrian prisoners-of-war (POW) camp in Theresienstadt, located in today’s Czech Republic. The Austrians commanded POWs to dig trenches on the front, and Klyushin refused to go, knowing those trenches would be used to fight Russia’s forces. He was punished ten times by being tied to a raised post and left for two hours and then by being beaten by Austrian soldiers so badly that “his back and hands turned black.”[2]

This disturbing account appears alongside many similar accounts in a book written under for the Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry, established in 1915 by Russia’s Council of Ministers “to investigate violations of the laws and customs of war by German and Austro-Hungarian troops.”[3] Other cruelty detailed by the commission included locking prisoners into small, sharp wired cages for a full day without food, or locking them nude in a casket for two hours with only a few small holes for air.

Unsurprisingly, Austria’s documentation of Russian POWs reveals a very different story. A 1915 Austrian documentary of a POW camp in Feldbach, Austria, produced under the leadership of the camp engineer and project manager, Felix Schmidt, depicts smiling, happy POWs, who participate in work activities around their camp, but also find time for theatrical performances, Ukrainian choir performances, and even “Russian games.”[4]

Judging the accuracy of either of these accounts is not within the scope of this paper – both sources are intrinsically biased. Likely these starkly different realities coexisted, with the average experience lying somewhere in between.

Only after World War I did the word “propaganda” develop negative connotations.[5] For the purposes of this essay, I will be using the term in its original definition to describe the presentation of information aimed to achieve political goals of influencing opinions and beliefs. During wartime, propaganda was crucial for the maintaining of morale of the home front and one’s own soldiers, as well as for demoralizing enemy soldiers, and it is important to understand how and why it is used for these purposes.[6]

Austrian propaganda used the cultural life of the POWs and the idea of “national culture” to support the Austro-Hungarian political narrative. References to the cultural life of POWs are frequent in Austrian depictions of their camps, yet these references are completely missing in Russian depictions. The Feldbach documentary shows prisoners mounting performances and engaging in games with each other. In at least one case, a camp newspaper invited POWs to contribute short stories and poetry for publication.[7] Additionally, prisoners of minority groups within the Russian Empire – such as Ukrainians held at Camp Freistadt – were given more such opportunities focused on their minority national culture. This was done in an attempt to destabilize the Russian Empire and the loyalty of its soldiers.

Culture holds a dual meaning in the context of this essay. Culture includes theater, music, literature, and other creative expressions, but it is also colored by the idea of national culture, one that reflects a specific ethnic identity. For Austria-Hungary – a multinational empire – these two meanings of culture often became intrinsically linked in depictions of the experiences of the POWs it held. Culture is fundamentally tied to nationalism and political goals.

Through this propaganda, Austria-Hungary projected an image of itself as a humane, scientifically-advanced, law-abiding empire that allowed multitudes of national cultures to flourish within it, unlike the Russian Empire. With its focus on culture, Austro-Hungarian propaganda aimed to boost the morale of its own citizens by showing respect towards diverse national cultures. It also sought to show itself to POWs as an alternative to the Russian Empire worth fighting for. Both strategies ultimately aimed to gather further support for Austria-Hungary in its wartime efforts against the Russian Empire.

Memory and Historiography of WWI POWs

In Russia, the First World War is sometimes known as the “forgotten war.”[8] The Revolutions of 1917, the Civil War, establishment of the USSR, and later, WWII, all stand out with much greater importance to both collective memory and historical study.

This is not helped by the lack of published memoirs from Russian POWs. Whether this lack came from the repression of trauma, lack of public interest, or a comparatively low literacy rate,[9] very few memoirs by WWI POWs were published beyond official government reports. Further, very few twentieth-century Russian historians studied World War I, and practically none studied the POWs’ experiences.

In Austria, while WWI was significantly more studied, foreign POWs were rarely written about. When they were mentioned, any negative conditions in the camps are either justified as the “principle of reciprocal treatment” (that Austria-Hungary had treated their captured POWs in the same way their enemies had treated the Austrian POWs), or depicted as a “paradise” such as shown in the propaganda videos.[10] Meanwhile, the experiences of Austrian POWs in Russian camps were comparatively heavily documented, particularly because many returning POWs published popular memoirs of harrowing experiences.[11]

This lack of historical scholarship persisted throughout the 20th century.[12] In the 2000s and 2010s, with the war’s centenary approaching, interest somewhat revitalized, including interest in POWs’ experiences.[13] Austrian historian Verena Moritz specifically researched the treatment of POWs from the Russian Empire and Russian historian Oksana Nagornaia developed complex arguments about the use of nationalism in propaganda by multinational empires during World War I.[14] It is upon their research that I hope to build.

The Hague Conventions and the Early War

World War I was the first major test of the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions. Born of ideas about peace and humanitarianism contrasted with fears of ever-more destructive weapons, the conventions established rules for warfare, promoted non-violent arbitration to prevent war, and established rules for the treatment of prisoners. Additionally, the Hague Conventions specified that “[POWS] must be humanely treated”.[15] However, “humane” was never defined (aside from work and housing conditions), which allowed for flexibility – and deniability – in the conventions’ application.

Somewhat ironically, on the eve of the first world war, public opinion was turning against violence. War was no longer romantic or chivalrous, as in the past.[16] Popular philosophies advocated against war, violence, and/or for systems of social justice to maintain peace.[17] European writers often presented war as senseless.

Inspired by Russian writer Ivan Bloch, whose 1898 book The Future of War argued that nations must use international courts to prevent war,[18] Tsar Nicholas II of Russia proposed the Hauge Conventions. He was perhaps equally inspired by the financial strain of keeping up with Germany and Austria-Hungary’s military advancements and hoped to abate war through diplomacy.[19] Twenty-six states, including Austria-Hungary, participated in both conventions.[20]

Specific to the treatment of POWs, the conventions agreed that prisoners should be paid wages for their labor and that said labor should have “no connection with the operation of war.”[21] POWs could be interned in towns or camps but not “confined” in extreme cases as required for safety. Their “board, lodging, and clothing” must be the same quality as that given to the soldiers of the government holding the POWs.[22]

Plans for a third Hague Convention were cut short following the assassination of Austria-Hungary’s heir to the throne by a Serbian nationalist. Austria itself then invaded the Kingdom of Serbia, despite that Kingdom having no connection to the nationalist. Russia, as the self-proclaimed defender of Slavic people (including Serbians), countered by invading Austria. The Austro-Hungarian government was almost immediately overwhelmed with large numbers of both POWs and refugees.[23] The government struggled from the outset to comply with the recent conventions.

Current estimates suggest that as many as 2.3 million people were held as POWs by Austria-Hungary during World War I. Of those, 1,269,000 were from the Russian Empire.[24] These estimates are higher than those reported by the empire itself; due to the government’s disorganization and the chaos of the war, many prisoners were not properly registered. In total, about fifty POW camps were constructed throughout the war, but the early camps were chaotic and disorganized, often leading to deadly results.[25]

Nationalism in Austria-Hungary and its POW Camps

Austria carefully approached its treatment of POWs not only in light of its very recent agreements at The Hauge, but also because of the place of national identity in its own domestic policy formation.

Austria-Hungary used the narrative of embracing the distinct national cultures within its borders to “justify its existence in terms of its ability to promote the development of its constituent nations.”[26] In other words, Austria-Hungary crafted a political narrative of itself supporting national cultures, so that related nationalist movements would support Austria-Hungary rather than seeking independence from it. Austrian scientists event developed a theory of six “Grundrassen” [main races], thirty “Unterrassen” [sub-races],[27] and later “mixes” of races[28] that was supposed to support Austria’s ability to support minority cultures. However, the “science” did assert that Eastern European cultures were inferior to those of the West.[29]

When the war created camps of POWs from all different parts of the Russian empire, Austria’s race scientists leapt at the research opportunity. One Austrian anthropologist, Rudolf Pöch, and his team conducted research on approximately 7000 individual prisoners, collecting hair samples, making plaster molds, taking photographs and filming the prisoners. They classified Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians as separate races – “Groß-, Klein- und Weißrussen” – and examined other “exotic mixtures of people” from within Russian Empire.[30]

Austria’s scientists and policy makers strove to “objectively” define national cultures, often with language as the primary marker, but also with cultural and national differences considered “fundamental in nature.”[31] Understanding these cultures was important for the empire because of the misconception, still popular today, that nationalist movements are inevitable “expressions of transhistorical ethnic groups.”[32] Therefore, holding the empire together required a systematic coopting and integration of these groups and their perceived political goals.

Thus, Austria-Hungary was defining national culture and applying its theories to POWs for political purposes. These definitions were considered objective and applied to the POW by their captors. Those POWs may not have necessarily agreed with the national identity being applied to them nor the stereotypes or national culture that came with the identity.[33]

Photos from Camp Feldbach

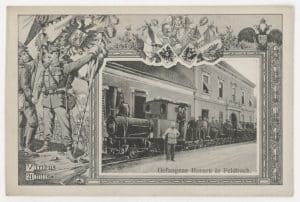

Camp Feldbach was the subject of postcards and photographs produced to distribute propaganda messages to Austrian civilians and to allies in Germany. POW postcards and photographs were generally popular, sold in train stations and in full book collections produced by individuals connected to the POW-camps or the wider imperial government.[34] Some of the photographs of Feldbach are more natural, but many are posed, with all the prisoners stood or sat facing the camera. Photographing POW-camps was obviously an approved activity, as there is nearly always an officer present. Photos were also given to researchers and journalists who then distributed them widely alongside their own commentaries.

Figure 1: Gefangene Russen in Feldbach [Imprisoned Russians in Feldbach], 1915, Feldbach, Stadt, K-11-H-57, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, Graz, Austria

The photographed prisoners, labeled as “Imprisoned Russians in Feldbach,” are posed sitting on a train in front of one of the main Feldbach buildings. An Austrian officer stands with authority in front, indicating a sense of control and discipline. The message of the postcard is clear: the disciplined prisoners provide an example of shared German-Austrian success. Implied is that, with further unity, further success would be forthcoming. It also reassures Austria’s German allies of Austria’s military strength and dedication to the alliance.

Photos from Feldbach nearly always pair prisoners with at least one Austrian officer, to emphasize Austrian control. In another photo, the prisoners stand in front of the railroad track, shovels in hand and ready to work. In a third, the prisoners stand in front of a bulletin board with a newspaper on it, apparently being briefed on the news of the day.[36] Always, they were shown guarded by a member of the disciplined, successful, and humane Austrian military.

Camp Feldbach Documentary: State Power and Racial Stereotypes

Film was also taken of Camp Feldbach to project the same images and ideas. However, to understand the films objectively, historical context is needed.

In late 1914 and early 1915, Austria-Hungary struggled to accommodate the sheer number of POWs they captured. A new camp constructed in the Austrian town of Knittelfeld saw its population grow from 600 to 19,000 over the course of just eleven days.[37] Overcrowding and the lack of sanitation facilities lead to disease and death for many prisoners. [38] Feldbach, less than a day’s travel from Knittelfeld, was chosen for the next camp. Commander Felix Schmidt, who, by the end of the war, oversaw the construction of multiple POW camps,[39] led the construction. It began on December 28th, 1914, the same day the first prisoners arrived. With no ready barracks, the captured soldiers were temporarily housed in citizens’ homes, while Russian prisoners from the Knittelfeld and nearby Thalerhof camps were brought in to help build the new camp.[40] The first barracks were finished by mid-January, and the new prisoners were resettled.[41]

A 30-minute documentary film, titled Feldbach Prisoner of War Camp and Building Operations began production in the camp in March of 1915, indicating that the need for propaganda production was also pressing and perhaps indicating that Feldbach was built to be a “model” camp for propaganda generation.

The documentary was produced by Sascha-Film, a company started by Count Alexandra Kolowrat-Krakowksy, who served as head of the film department in the wartime news headquarters. Sascha-Film produced a weekly newsreel during wartime, as well as short-play feature films,[42] such as the documentary in question, which includes title cards explaining the silent footage and the camp’s history. While it is not clear where the film was screened, it was clearly intended for distribution to the Austro-Hungarian public.

Focusing on daily life and the work of the prisoners, the film additionally showcases camp cultural activities. Footage is structured somewhat chronologically beginning with a brief title card explaining the camp’s construction, which is followed by a panoramic view of the camp. We then see some of the 35,000 Russian Empire POWs arrive by train. They are marched by camp guards first to the “Lagerbad” [the camp baths], where they strip, bathe, receive vaccinations, and receive new prisoner outfits, which they are shown wearing when leaving the bathhouse. This whole process is depicted as smooth and organized, with a formal transfer of the prisoners to the officers at the camp, and with precise marching and herding of the compliant prisoners from location to location. Thus, again, the camp and the Austrian military are presented as organized, humane, and disciplined.

This image, of course, contradicts the experience of the Knittelfeld prisoners and even the first prisoners that arrived for Feldbach. The film instead plays specifically to the Hague Convention requirements for the treatment of prisoners, showing the prisoners given treatment much as newly recruited soldiers might expect. While Feldbach was apparently built as part of genuine efforts to comply with the convention, wider changes to Austria’s POW camp system were more widely implemented only in late 1915 and 1916. Thus, this propaganda shows an idealized version of prisoner treatment in early 1915. That Feldbach had been built to help alleviate the terrible conditions in Knittelfeld, is not mentioned at all. This ideal was reflected in other efforts as well. A “War Exhibition” held in Vienna included a model POW hall (new, unused, and bereft of actual POWs) to “assure visitors that Austria treated its enemy decently.”[43]

The focus on prisoner hygiene played into racialized views. The narrative of Austria bringing order and cleanliness was presented as the spread of a superior civilization to peoples like the “filthy” and “unkempt” Slavs.[44] Much of this philosophy originated with German nationalists but some Austro-Hungarian official policies supported this colonialist narrative.[45]

National Cultures in the Camp Feldbach Documentary

Historians Gilly Carr and Harold Mytum argue that in POW-camps, “[creativity] was a necessity—a prerequisite—for enduring and surviving captivity.”[46] They also write about the use of culture as a “counter-narrative of captivity,” encouraging historians to use art created by the internees to better understand the lived experiences of POWs, in contrast to depending on the authorized and official narratives created by the governments and captors.[47]

The Feldbach documentary is interesting to analyze within this lens. After introducing the camp itself, the documentary then shifts to introduce us to the prisoners’ work and cultural life within the camp.[48] It is an authorized narrative from those connected to the Austro-Hungarian imperial government and military, but it also focuses heavily on the cultural life discussed by Carr and Mythum, an aspect to imprisonment rarely found in official narratives.

We are first shown a section called “Types of prisoners”, which features unlabeled shots of different prisoners alternating between smiling at the camera and talking to somebody right off-camera. We are left to assume that the viewer should know and recognize the obvious types. While this is a friendly introduction to the prisoners, it also presents them as scientific samples through orderly “mug shots” from standard angles.

This is then complimented by four sections on culture beginning with “Performance of a Russian Play (Realism).” Russia was, at the time, famous for its realist theatrical productions. Labeling this section of film “Realism” also suggests its audiences that the actions, costumes, and set presented would be accurate.

In the clip, five actors are shown with no audience visible. On set is a wooden table covered with a tablecloth. On the table is a glass and a bottle and, next to it, a stool. A peasant hut has been recreated with windows, a door, and a straw roof. Dressed in traditional Russian peasant outfits, one group of characters meets another at the hut. They are wrapped in boisterous discussion as they greet each other, laugh, and the guest characters are invited to the table and poured a drink, playing into stereotypes of Russians as loud, heavy drinkers.

Notably, two of the five characters are clearly presented as female, wearing long dresses, and one gives a romantic half-hug to one of the male characters. Women were not likely to have been at the men’s camp to participate in the theatrical performances, and thus it is likely that men were playing the roles as “female impersonators,” such as was common in Plennytheaters[49] in other POW-camps.[50] However, the character’s actual gender is not clear nor is it clear if the crossdressing held meaning within the film.

The next section is labeled “Ukrainian choral singing with dance.” Clearly filmed in the same location as the Russian play, the set is the same and the female-dressed characters are still in costume, standing amongst the crowd. They clap as two dancers, dressed in fur hats, loose pants, white blouses with a tie (or string) down the front, come forward and perform a traditional squat dance (prisiadki). Thus, the documentary draws a hard line between Ukrainians and Russians through its labeling of the clips, yet the two ethnicities are shown together, interacting in a positive light. Ukrainians were a significant minority culture within the Austro-Hungarian Empire and thus representing them living happy, healthy lives was particularly prudent.

In the section on “Russian games,” we first see prisoners running around with other prisoners on their shoulders. It then transitions to two groups lined up with linked arms – the left group mostly dressed in black, the right mostly dressed in white. At the raising of a hat by a black-clad man in the middle, the two lines charge at each other rowdily, seemingly trying to break through the line. Many successfully do, wrestling with the person opposite from them in the line. This section’s inclusion is an interesting one. It is the only evidence we have of games played by the prisoners. Also, by indicating the “Russian” in “Russian games” the footage others the playful behavior, tying it to the prisoners’ perceived ethnic identities.

The final section showcases “Circassian[51] dance.” A man is shown wearing a coat over his blouse, and a tall fur hat. As he picks grass, another man in the background sneaks out from the bushes. He holds a long stick of some sort, grabs the first man, and ‘stabs’ at his chest, throwing him to the ground. He then circles him, his arms outstretched as he does, in a dance-like routine. This celebration of murder and violence is thus directly connected with Circassians and the “wildness” stereotype associated with Caucasian peoples.[52]

How the multinational Austro-Hungarian audience may have perceived this footage is hard to know. The footage itself seems to assume that its audience would be intelligent and curious, with an interest in the scientific study of cultures and identities. Other Austrian films also focused on scientific study. For instance, the 1916 film Prisoner of War Camp[53] features Rudolf Pöch, an Austrian medical doctor and anthropologist, making a mold of a Russian POW’s head.

The Feldbach documentary serves a propagandistic purpose to show that the Austro-Hungarian government actively encouraged the expression of national culture among their POWs. Although most clips play into ethnic stereotypes, they can also be interpreted as the government’s expressing respect for minority cultures, including those that Austria-Hungary worried might otherwise formulate separatist movements within its borders.

Ukrainian Nationalism in Austria Hungary

Austria Hungary had long made coopting nationalist movements part of its domestic political policy. It had done so with considerable success, as well – with many influential nationalist leaders and organizations supporting the imperial government that ruled them. This was particularly true for Ukrainians.

Kost Levytsky was an ambassador and prosecutor for the Austro-Hungarian government, and also a leader of the Galician Ukrainian National Movement, and president of a political and national organization known as the Supreme Ukrainian Council.[54] A manifesto issued by the Council on August 3, 1914 warned that “Russia’s victory could bring the Ukrainian people of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy the same yoke under which 30 million Ukrainian people suffer in the Russian Empire.”[55] It called for Ukrainians to give the Habsburg Empire “all material and moral strength, so that the historical enemy of Ukraine may be destroyed,” and emphasized that by doing so, Ukrainians would be supporting an empire that allowed Ukrainian nationalism to “freely develop.”[56]

Andrii Sheptyts’kyi, the Metropolitan of Galicia for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and a towering figure of Ukrainian public life, wrote a similar declaration on August 21, 1914. He blamed the war on the tsar’s inability to “bear the fact that in the Austrian state, we have freedom of faith and nationality, he wants to wrestle this freedom from us and put us in shackles.”[57] Sheptyts’kyi also wrote that, “By the will of God we are united with the Austrian state and the Habsburg dynasty; our fortune and misfortune are one and the same.”[58]

In these addresses, Austria-Hungary is depicted as a safe haven for and supporter of the Ukrainian people, in direct contrast to their enemy, the Russian Empire. Ukrainians nationalist culture is seen as tied to Austria-Hungary’s success over Russia. Austria-Hungary, presented as humane and enlightened, is presented as deserving of civilian and military support from Ukrainians.

Ukrainian Nationalism Fostered at the Freistadt POW Camp

Ukrainian prisoners were given particularly special treatment in an effort at nation-building by Austria-Hungary, and often using trusted Ukrainian nationalist organizations. At the Freistadt POW Camp, for instance, these efforts were led by the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (ULU), one of the strongest nationalist movements within Austria-Hungary. The ULU had been formed by Ukrainian Socialists that had fled Russia after the failed 1905 Russian Revolution and settled in the eastern Austria-Hungarian territories of Galicia and Bukovina, which already had significant Ukrainian populations. Within their wider goal of securing the liberation of Ukraine with international support, they secured from Germany and Austria-Hungary the right “to assemble all the war prisoners of the Russian army of Ukrainian descent in special camps where delegates of the ULU would take care of them and conduct cultural and political education.”[59] In addition to Freistadt, the ULU conducted activities in five POW-camps in Germany.

According to a report on the activities of the Ukrainian education committee in Freistadt dated in 1914-1915, German was taught daily from the establishment of the camp, with 70-80 participants in each course and with oversight from Austrian generals. [60] There were also lessons including agriculture, art, and Ukrainian grammar and literary history. Social science courses included “the national question,” Ukrainian history, philosophy, and cultural history.[61] Music courses were taught where the music teacher “devoted his attention above all to Ukrainian national music.”[62] By emphasizing German language alongside Ukrainian national history and culture, the camp connected the idea of Ukrainian nationalism to German language and to Austria-Hungary. This also encouraged prisoners to think of integrating into Austrian society.

As historian Oksana Nagornaia analyzes, this was not an uncommon strategy for the multinational empires participating in WWI.[63] While all the empires had minorities fighting in their armies, each empire assumed, paradoxically, that national minorities fought for the enemy’s armies “not out of conviction, but out of coercion, and were therefore predisposed to cooperate with the enemy to win independence.”[64] The Russian Empire used a pan-Slavic strategy, encouraging any Slavic POWs they had captured from Austria-Hungary to embrace their Slavic similarities and join Russia.[65] In contrast, Austria-Hungary encouraged Slavic races to see themselves as different and, above all, freer under Austria-Hungary.[66]

Some Ukrainians held at Camp Freistadt were Russian speakers that did not speak Ukrainian.[67] Nevertheless, the Austro-Hungarian leadership believed that, as a racially distinct group, these individuals could still have a separate national consciousness “inspired” in them.[68] This inspiration was considered a serious and scientific task. The intelligence officers at Freistadt were instructed to leave the “propaganda” to the education committee from the ULU, as a German officer would be unable to “properly lead an education that requires knowledge of the innermost nature, emotional life, and receptiveness of the people to be educated.”[69] Their role was to support the committee and forward its requests to military authorities.

The cultural activities at Freistadt are evidenced in multitudes of photographs, of which there are significantly more than from Camp Feldbach. Many of the photos, especially those showing theatrical productions, were also reprinted in postcard form, which prisoners could send to their families in the Russian Empire, showing them the quality of life and variety of Ukrainian cultural opportunities that Ukrainians were offered in the Austro-Hungarian camps.[70]

Figure 2. Фотографії полонених табору [Photographs of the POWs], 1914, Collection number 103, Fund 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo , Kyiv, Ukraine.

A separate organization, the “Provisionary Central Bureau of the Unification of Jews on the Occupied Territories of Ukraine” worked with Jewish-Ukrainian POWs. In a statement of thanks directed at the imperial army leadership, the organization argued that the Jewish minority in Russia also lived under “political and national oppression” and that the “Jewish organization in the Ukrainian camp is preparing the mutual involvement of these two peoples [Ukrainians and Jews] in the upcoming struggle for national revival.” [74]

The Bureau also focused on national culture – music, poetry recitals, and plays in the Yiddish language (with plot summaries offered in Ukrainian to the audience). In a report to the ULU, the Bureau emphasized that they were prioritizing the performances of plays that are “based on Jewish-Ukrainian relationships in Ukraine.”[75]

Supporting these organizations worked to show the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a safe haven for minority nationalities, encouraging its own minorities to support it and, at the same time, working to turn POWs from ethnic minority populations against the Russian Empire.

Conclusion

Austria-Hungary, a multiethnic empire, actively promoted itself as a protector of national cultures to serve its political aims. It incorporated the influx of POWs from the Russian Empire into this narrative through educational and cultural activities, hoping to shore up the support of its own citizens and turn national minority POWs against the empire it fought.

Through activities at POW camps such as Camp Feldbach and Camp Freistadt, and propaganda materials such as postcards and films based on these activities, Austria-Hungary showed itself as an active supporter and protector of national cultures, often with the support of organizations fostering nationalism within its own borders.

Although the Austro-Hungarian Empire lost the war and fragmented with the end of World War I, it offers an excellent case study of the connection between nationalism and culture during this crucial period of change. With a better understanding of how Austria-Hungary, as a multinational empire, used nationalism and the cultural activities of the prisoners in its propaganda, historians can approach propaganda from other multinational states with new perspectives to better understand their use of culture, ethnicity, and nationalism.

Primary Sources

Bloch, Ivan. The Future of War in its Technical, Economic and Political Relations: Is War Now Impossible? Translated by R. C. Long. Doubleday & McClure, 1899.

Colonel general Steger-Steiner to V. Malik, translated into Russian, July 13, 1918,“Ответ военного министерства Австро-Венгрии на запрос депутата австрийской Нижней палаты парламента В. Малика о положении военнопленных в России. Вена, 13 июля 1918 г.“ ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ БИБЛИОТЕКА ИСТОРИЧЕСКИХ ДОКУМЕНТОВ, Военно-исторический архив Венгерской народной армии (HIL), Web.

Gefangene Russen in Feldbach [Imprisoned Russians in Feldbach]. Feldbach, Stadt, K-11-H-Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, Graz, Austria.

International Peace Conference. “Annex to the Convention, Chapter II: Prisoners of War.” In Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907. Web.

Kriegsgefangenenlager und Betriebe der Bauleitung Feldbach [Feldbach prisoner of war camp and building operations], 1915. Filmarchiv Austria, Web.

Krivtsov, Alexey. Жизнь русских воинов в плену [The Life of Russian Soldiers in Captivity], 1916, Russian army and civil prisoners of war Collection, Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, St. Petersburg, Russia. Web.

“Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria” Collection. Tsdavo, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Русские в плену у австрийцев [Russians in captivity from the Austrians]. Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, 1916. Web.

Roserrati, R. “The Sinking of the Viribius Unitis: Official Report of the Destruction of the Austrian Dreadnought by Two Italian Officers.” In Current History (1916-1940) 9, no. 3 (1919): 439-99, Web.

Russia Council of Ministers, Об образовании Чрезвычайной следственной комиссии для расследования нарушений законов и обычаев войны австро- венгерскими и германскими войсками [On the formation of an Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry to investigate violations of the laws and customs of war by Austro-Hungarian and German troops], 1915. Damages. War Crimes. Collaborationism Collection, Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, St. Petersburg, Russia. Web.

Secondary Sources

Berner, Margit. “Die “Rassenkundlichen” Untersuchungen der Wiener Anthropologen In Kriegsgefangenlagern 1915-1918″ Zeitgeschichte 30, no. 3 (2003): 124-136. Web.

Best, Geoffrey. “Peace Conferences and the Century of Total War: The 1899 Hague Conference and What Came After.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-) 75, no. 3 (1999): 619-634. Web.

Caron, David D. “War and International Adjudication: Reflections on the 1899 Peace Conference.” The American Journal of International Law 94, no. 1 (2000): 4-30. Web.

Carr, Gilly and Harold Mytum. “The Importance of Creativity Behind Barbed Wire: Setting a Research Agenda.” In Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War: Creativity Behind Barbed Wire, 1-15. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Chen, Theodore Hsi-En, Shimahara, Nobuo, Graham, Hugh F, Naka, et al. “Education | Definition, Development, History, Types, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 3, 2025. Web.

Demm, Eberhard. Censorship and Propaganda in World War I: A Comprehensive History. Bloomsbury: London, 2019.

Fitch, Nancy. “The Face and Race of the Enemy: German POW Photographs as a Weapon of War.” In Out of Line, Out of Place: A Global and Local History of World War Internments, edited by Rotem Kowner and Iris Rachamimov, 128-155. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2022.

Greenberg, David. “The Ominous Clang: Fears of Propaganda from World War I to World War II.” In Media Nation: The Political History of News in Modern America, edited by Bruce J. Schulman and Julian E. Zelizer, 50–62. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017. Web.

Hansak, Peter. “Kriegsgefangene im Gebiet der heutigen Steiermark 1914 bis 1918.” Zeitschrift der Historischen Vereines für Steiermark Jahrgang 84 (1993): 261-311.

Healy, Maureen. Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Cambridge: University Press, 2004.

Judson, Pieter M. The Habsburg Empire: A New History. Cambridge: The Belknap Press, 2016.

Kolonitskii, Boris. “Russia and World War I: The Politics of Memory and Historiography, 1914-1918.” In The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present, edited by Christoph Cornelissen and Arndt Weinrich, 223-262. Berghahn Books, 2021.

Lauwerys, J.A., Moumouni, A., Arnove, R.F., Riché, P., Szyliowicz, J.S., Vázquez, J.Z., Naka, A., et al. “Revolutionary patterns of education.” Encyclopedia Britannica. July 3, 2025. Web.

“Levytsky, Kost.” Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Accessed July 14, 2025. Web.

Marksteiner, Franz, and Margit Slosser. “Where Is the War? Some Aspects of the Effects of World War One on Austrian Cinema.” In The First World War and Popular Cinema: 1914 to the Present, edited by Michael Paris, 247–60. Edinburgh University Press, 1999. Web.

Moritz, Verena. “The Treatment of Prisoners of War in Austria-Hungary 1914/1915.” In 1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I, edited by Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer, and Samuel R. Williamson, 23:233–48. University of New Orleans Press, 2014. Web.

Nagornaia, Oksana S. ““Гости кайзера” и “политическая декорация”: Солдаты и офицеры многонациональных империй в лагерях военнопленных Первой мировой войны” [“Guests of the Kaiser” and “political decorations”: Soldiers and officers of multinational empires in POW camps during World War I]. Ab Imperio 4 (2010): 225-244. Web.

Smal-Stocki, Roman. “Actions of the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” during World War I,” The Ukrainian Quarterly 15, issue 2 (1959): 169-174.

Rachamimov, Iris. “The Disruptive Comforts of Drag: (Trans)Gender Performances among Prisoners of War in Russia, 1914–1920.” The American Historical Review, vol. 111, no. 2 (2006): 362–82. Web.

Rathkolb, Oliver. “Austrian Historiography and Perspectives on World War I: The Long Shadow of the “Just War,” 1914-2018.” In The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present, edited by Christoph Cornelissen and Arndt Weinrich, 192-222. Berghahn Books, 2021.

Steppan, Christian. “The Camp Newspaper Nedelja as a Reflection of the Experience of Russian Prisoners of War in Austria-Hungary” In Other Fronts, Other Wars?, 167-195. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2014.

Footnotes

[1] Жизнь русских воинов в плену [The Life of Russian Soldiers in Captivity] by Alexey Krivtsov, 1916, BBC 63.3 (2) 534-68.7, Russian army and civil prisoners of war Collection, Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, St, Petersburg, Russia, Web, 5 (hereafter cited as Жизнь русских, Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library). All translations from German and Russian have been completed by me unless otherwise stated. [2] Жизнь русских, Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, 5. [3] Об образовании Чрезвычайноrй следственной комиссии для расследования нарушений законов и обычаев войны австро- венгерскими и германскими войсками [On the formation of an Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry to investigate violations of the laws and customs of war by Austro-Hungarian and German troops] by the Russia Council of Ministers, 1915, BBK 63.3 (2) 535-68-36y11, Damages. War Crimes. Collaborationism Collection, Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, St. Petersburg, Russia, Web, 6. [4] Kriegsgefangenlager und Betriebe der Bauleitung Feldbach [Feldbach prisoner of war camp and building operations], 1915, 12:28, Web. [5] David Greenberg, “The Ominous Clang: Fears of Propaganda from World War I to World War II,” in Media Nation: The Political History of News in Modern America, ed. Bruce J. Schulman and Julian E. Zelizer (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 52, Web. [6] Eberhard Demm, Censorship and Propaganda in World War I: A Comprehensive History (Bloomsbury Academic: London, 2019), 27. [7] Christian Steppan, “The Camp Newspaper Nedelja as a Reflection of the Experience of Russian Prisoners of War in Austria-Hungary,” in Other Fronts, Other Wars?, ed. Joachim Bürgschwentner, Matthias Egger, and Gunda Barth-Scalmani (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2014), 190. [8] Boris Kolonitskii, “Russia and World War I: The Politics of Memory and Historiography, 1914-1918,” in The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present, ed. Christoph Cornelissen, Arndt Weinrich (Berghahn Books, 2021), 223. [9] The Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire had a literacy rate of 83.5% for those over the age of eleven years old by 1910. In contrast, the Russian Empire had only about a 40% literacy rate by the start of World War I. See: Pieter M. Judson, The Habsburg Empire: A New History. (Cambridge: The Belknap Press, 2016), 335; J.A. Lauwreys, A. Moumouni, R.F. Arnove, P. Riché, et al., “Revolutionary Patterns of Education,” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 3, 2025, Web. [10] Verena Moritz, “The Treatment of Prisoners of War in Austria-Hungary 1914/1915,” in 1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I, ed. Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer, and Samuel R. Williamson (University of New Orleans Press, 2014), 235. [11] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 236; Oliver Rathkolb, “Austrian Historiography and Perspectives on World War I: The Long Shadow of the “Just War,” 1914-2018,” in The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present, ed. Christoph Cornelissen, Arndt Weinrich (Berghahn Books, 2021), 199. [12] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 235. [13] For more on Austrian historiography of World War I, see Rathkolb, “Austrian Historiography.” For more on Russian historiography of World War I, see Kolonitskii, “Russia and World War.” [14] Dr. Verena Moritz has many works on the experiences of POWs from the Russian Empire in Austria-Hungary, but I will be primarily building off her research demonstrated in her article “The Treatment of Prisoners of War in Austria-Hungary 1914/1915,” in 1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I, ed. Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer, and Samuel R. Williamson (University of New Orleans Press, 2014), 233-248. Dr. Oksana Nagornaia also has many impressive contributions to this subfield, but I will be particularly applying her theories about multinational empires and how they aimed propaganda at POWs, which she outlines in her article ““Гости кайзера” и “политическая декорация”: Солдаты и офицеры многонациональных империй в лагерях военнопленных Первой мировой войны” [“Guests of the Kaiser” and “political decorations”: Soldiers and officers of multinational empires in POW camps during World War I], Ab Imperio 4 (2010): 225-244. Web. [15] Annex to the Convention, Chapter II: Prisoners of war, Art. 4, in Convention (IV). [16] David D. Caron, “War and International Adjudication: Reflections on the 1899 Peace Conference,” in The American Journal of International Law 94, no. 1 (2000), 7. Web. [17] Caron, “War and International,” 8. [18] Ivan Bloch, The Future of War in its Technical, Economic and Political Relations: Is War Now Impossible?, trans. R. C. Long (Doubleday & McClure, 1899). [19] Geoffrey Best, “Peace Conferences and the Century of Total War: The 1899 Hague Conference and What Came After” in International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-) 75, no. 3 (1999), 622. Web. [20] Notably, despite the goal of the Hague Conventions to establish international laws, twenty of these states were European. The Americas were represented by the United States and Brazil, and Asia was represented by China, Japan, Persia, and Siam. Best, “Peace Conferences,” 623. [21] Annex to the Convention, Chapter II: Prisoners of war, Art. 6, in Convention (IV). [22] International Peace Conference, “Annex to the Convention, Chapter II: Prisoners of war,” Art. 5 in Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907, 1907, Web. (Hereafter Convention (IV)) [23] Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 408. [24] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 237, 239. [25] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 237. [26] Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 270. [27] Margit Berner. “Die “Rassenkundlichen” Untersuchungen der Wiener Anthropologen in Kriegsgefangenlager 1915-1918″ Zeitgeschichte 30, no. 3 (2003): 125. Web. [28] Berner, “Die “Rassenkundlichen,”” 125. [29] Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 73. [30] Berner, “Die “Rassenkundlichen,”” 126. [31] Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 269. [32] Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 9. [33] Ibid; Nagornaia, “Guests of the Kaiser,” 233. [34] Nancy Fitch, “The Face and Race of the Enemy: German POW Photographs as a Weapon of War,” in Out of Line, Out of Place: a global and local history of World War internments, ed. Rotem Kowner and Iris Rachamimov (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022), 128-132. [35] The ship was eventually sunk during the war. For more, see: R Roserrati, “The Sinking of the Viribus Unitis: Official Report of the Destruction of the Austrian Dreadnought by Two Italian Officers,” in Current History (1916-1940) 9, no. 3 (1919): 439-99, Web. [36] Gefangene Russen in Feldbach, 1915, Feldbach, Stadt, K-11-H-57, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, Graz, Austria. [37] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 237. [38] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 240. [39] He seems to have previously built the Hungarian POW-camp Kenyermezö and the internment camp Thalerhof, though the dates of the building of these camps are not listed in the source. See Peter Hansak, “Kriegsgefangene im Gebiet der heutigen Steiermark 1914 bis 1918“ in Zeitschrift der Historischen Vereines für Steiermark Jahrgang 84 (1993), 276. [40] Interestingly, the date listed as the starting date for building in the documentary itself – January 1st, 1915 – differs from the evidence gathered by historian Peter Hansak in “Kriegsgefangene,” 277. [41] Hansak, “Kriegsgefangene,” 276-7. [42] Franz Marksteiner und Margit Slosser. “Where is the War? Some Aspects of the Effects of World War One on Austrian Cinema,” in The First World War and Popular Cinema: 1914 to the Present, ed. Michael Paris (Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 250-51. [43] Maureen Healy, Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. (Cambridge: University Press, 2004), 115. [44] Fitch, “The Face,” 139. [45] Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 73-4. [46] Gilly Carr and Harold Mytum, “The Importance of Creativity Behind Barbed Wire: Setting a Research Agenda,” in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War: Creativity Behind Barbed Wire (Routledge: New York, 2012), 3. [47] Carr and Mytum, “Importance of Creativity,” 10. [48] Kriegsgefangenlager und Betriebe, 12:28 – 13:48. [49] Plennytheaters comes from the Russian word for a prisoner – пленный – and was used in German to describe the POW theaters. [50] See Iris Rachamimov, “The Disruptive Comforts of Drag: (Trans)Gender Performances among Prisoners of War in Russia, 1914–1920.” The American Historical Review, vol. 111, no. 2 (2006): 362–82. Web. This article offers a thorough analysis of the role that gender presentation played for Austrian soldiers in theater presentations in Russian POW-camps. More research will need to be done to see if a similar environment developed in Austro-Hungarian camps by Russian POWs participating in theater. [51] Circassians are an ethnic group that have historically lived in the Caucasus region, a region that had been under Russian rule since the rule of Peter the Great, though often contested in wars against Persia and the Ottoman Empire. [52] Fitch, “The Face,” 139. [53] Kriegsgefangenenlager [54] “Levytsky, Kost,” Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, accessed July 14, 2025, Web. [55] Манифест Главного Украинского Совівта, 1914, Collection number 5, Fund 4405, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo , Kyiv, Ukraine. [56] Ibid. [57] Andrei Sheptitsky, Звернення мітропаміта Шептицького А. до населення прикордонних сел Галичини з закликам залишатись вірним Австро-Угорській монархії, 1914, Collection number 8, Fund 4405, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo , Kyiv, Ukraine; all translations from Ukrainian have been completed thanks to professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Dr. Valeria Sobol of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. [58] Ibid. [59] Roman Smal-Stocki, “Actions of the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” during World War I,” The Ukrainian Quarterly 15, issue 2 (1959): 170-1. [60] Bericht des „Ukrainischen Unterrichtsausschusses“ (Vertrauensmänner des „Bundes zur Befreieung der Ukraina“) über seine Tätigkeit am k.u.k. Kriegsgefangenlager in Freistadt, 1914-1915, Collection number 14, Fond 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo, Kyiv, Ukraine. [61] Ibid. [62] Ibid. [63] See her article, ““Гости кайзера” и “политическая декорация”: Солдаты и офицеры многонациональных империй в лагерях военнопленных Первой мировой войны” [“Guests of the Kaiser” and “political decorations”: Soldiers and officers of multinational empires in POW camps during World War I], Ab Imperio 4 (2010): 225-244. Web. [64] Nagornaia, “Guests of the Kaiser,” 226. [65] Ibid. [66] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 239. [67] Based on the list of prisoners in Freistadt, most prisoners spoke in both Russian and Ukrainian, with some also speaking French, German, or Polish, and some only speaking Ukrainian. However, some individuals listed did not speak Ukrainian. They were likely identified as Ukrainian due to being born in territories considered historically Ukrainian, such as the cities of Kyiv or Kharkiv, a method used on occasion by Austro-Hungarian officials for identifying the nationality of the captured prisoners. See: Nagornaia, 231; Списки полонених. Є біографічні дані, 1918, Collection number 34, Fund 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo, Kyiv, Ukraine. [68] Moritz, “The Treatment,” 239. [69] Guidelines for the intelligence officers and the education committee in the Ukraine camp, Collection number 14, Fund 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria”, Tsdavo, Kyiv, Ukraine. [70] See: Фотографії полонених табору, 1914, Collection number 103, Fund 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo , Kyiv, Ukraine. [71] In contrast to Camp Feldbach, there is evidence that it was the male POWs who played female roles in Camp Freistadt theatrical performances. A cast list written on the back of a photograph of a group of people in costumes has female roles played by people with masculine-endings in their surnames. Again, more research will need to be done to have a better understanding of this gendered aspect of POW-theaters in Austria-Hungary. See Footnote 54. [72] Moritz, “Treatment,” 239. [73] Програми концертів і афіш артистичної секції товариства, 1915-1916, Collection number 151, Fund 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo , Kyiv, Ukraine. [74] Звіт про діяльність єврейського просвітнього гуртка, 1916, Collection number 18, Fund 4404, Description 1, Collection “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the POW-camp in Freistadt Austria,” Tsdavo , Kyiv, Ukraine. [75] Ibid.More From Vestnik

This paper is published here as part of Vestnik. See all Vestnik papers on this site here.

Vestnik was launched by SRAS in 2004 as one of the world’s first online academic journals focused on showcasing student research. We welcome and invite papers written by undergraduates, graduates, and postgraduates. Research on any subject related to the broad geographic area outlined above is accepted. This includes but is not limited to: politics, security, economics, diplomacy, identity, culture, history, demographics, language, religion, literature, and the arts. Find out more here.