The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story by Olga Tokarczuk, translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones is an expertly woven folk horror story that grapples with the explosion of philosophies that overtook Europe at the turn of the last century as well as questions of gender and the ways in which we interpret the world around us.

The story is set in 1913, just before Europe would descend into the violence of WWI and, indeed, many of the places named in the story are located near borders and would be located in entirely different states soon after the story concludes. While the story itself does not dwell on this, for those that know their history, these facts help provide extra tension and an increased sense of alienation as the story unfolds.

The History Sets the Scene

The story centers on Mieczysław Wojnicz, an anxious, naive, and sickly Polish engineering student from Lwów. In 1913, Lwów was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire but had previously been ruled by Poles for more than four centuries. Today, it is modern day Lviv and part of Ukraine.

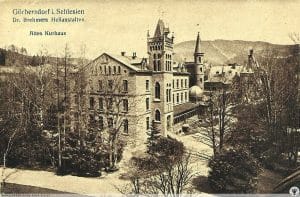

Dr. Hermann Brehmer’s Sanatorium in Sokołowsko (as posted at Sokolwkso.org)

The tale opens with Mieczysław’s arrival at a sanatorium in the village of Görbersdorf, then part of Prussia, a German state, but soon to be part of Poland, where it remains today, renamed to Sokołowsko. Görbersdorf really did have a famous sanatorium at that time, specialized in treating tuberculosis. It is for this purpose that Mieczysław has arrived.

He is shown to his quarters in the Guesthouse for Gentlemen, as he awaits placement at the Kurhaus (spa house). At the guesthouse, he meets fellow patients, a motley group of men from across Central and Eastern Europe. Aided by Schwarmerei, a medicinal liqueur infused with hallucinogenic mushrooms offered to them at every turn, the men spend their days debating all manner of subjects from politics, to religion, philosophy, and art.

Each man represents a different philosophy from prewar Europe. Thus, in their banter we can hear nearly all of Europe arguing with itself. We have the Catholic traditionalist, a socialist-humanist, a theosophist, as well as a character representing the cutting-edge arts movements and a psychoanalyst, representing the cutting-edge scientific community.

In another interesting historical reference, the Görbersdorf sanatorium inspired the Waldsanatorium in Davos, Switzerland. That institution was the setting of Thomas Mann’s German classic The Magic Mountain. That story follows Hans Castorp, a young man visiting his sick cousin in the decade before World War I. While there, Hans is diagnosed with early symptoms of tuberculosis and persuaded to undergo treatment. During his extended stay, he meets a host of characters, who all serve as allegories to various pre war European ideas. Tokarczuk’s novel can be understood as being in direct conversation with The Magic Mountain, drawing from its plot structure and central themes of illness, death, and magic.

Misogyny and Murder

Despite the variety of these characters and the differences in the worldviews, and no matter where their conversation begins, the men always land on the subject of women and their undisputed inferiority. To craft these arguments, Tokarczuk draws on a number of male thinkers including Darwin, Ovid, Freud, Thomas Aquinas, and Joseph Conrad, as explained in her author’s note.

Wojnicz is no stranger to this rhetoric–his mother died in childbirth and his father and uncle have made it their mission to imbue masculinity into the young man. From hunting trips as a young child, to his prescribed field of study (engineering and sanitation), and ultimately to his placement at the men’s guesthouse, Wojnicz’s life has been tailored to make him more of a man. Even his beloved childhood nurse, Gliceria, was dismissed when Wojnicz senior felt she over-coddled the boy.

Despite these efforts (or perhaps because of them), Wojnicz has never felt fully welcome in male spaces, preferring to stay quiet and observe. He is blighted by his naivety and sexual immaturity. On the other hand, his lack of familiarity with women has made him both susceptible to the beliefs of his peers and curious about the hidden lives of the women around him.

Early in his stay, Wojnicz discovers a dead body lying unattended on the dining room table. Alarmed, he assesses the body, realizing it belongs to the woman who served his breakfast that morning, and thinks how “only now, after death, could she be seen in her entirety.” (29) Unlike the male patients, the women living on the sanatorium’s grounds reside in the margins, flitting in and out to labor and seldom interacting with the men, so only now, after she has passed, can Wojnicz truly observe her. Moments later, the proprietor of the guesthouse appears and tells Wojnicz that the woman was not a servant but in fact his wife whom he found hanged earlier that day. While the widower does not feign concern, Wojnicz is deeply troubled by his discovery and the woman’s image is burned in his mind. From then on, the young man’s experience at the sanatorium is tinted by shadows in his peripheral vision and strange noises only he seems to hear.

As readers, we are also privy to these noises, to what becomes clear is a collective “we,” observing the sanatorium. An assuredly female perspective, inspired by the shape shifting entity known as empusa in Greek mythology, is interspersed with Wojnicz’s narrative through short breaks in chapters. Whatever form this entity takes, whether it be the landscape, mist, or a physical manifestation of a woman, it is always watching and at times interfering with the human world.

Mieczysław’s paranoia is intensified when Thilo, the art history student from Berlin, informs him of a terrifying local recurrence: each November, one man is violently murdered in the forest. No one can explain why, or at least no one will to Wojnicz, and as November draws near, Wojnicz begins to fear that he may be next.

Self-Realization in a Complex Reality

While the sickly hero appears passive at the start, Wojnicz gains agency through self discovery and acceptance at the sanatorium. Separated from his father and given a glimpse of the world beyond his hometown, the young man is empowered for the first time in his life. He keeps a recipe log of the Silesian delicacies he tries, forms a friendship with Thilo, and develops a curious daily habit kept secret from all. Wojnicz will surprise readers with his complexity, growth, and bravery, as he discovers himself and in turn, the reality of his landscape.

Structurally, Tokarczuk’s narrative feels rather haphazardly stitched together. A character will say something in passing that won’t be explained for another 50 pages. While Wojnicz is being treated for tuberculosis, another underlying and more serious illness is hinted at, finally being revealed almost two-thirds of the way through the book. This disjointed structure is likely a representation of the disjointed thoughts of the characters themselves, addled by illness and hallucinogenic liquor.

Furthermore, Tokarczuk uses this structure, her character’s conversations, and the empusa as a presence to challenge a simple, binary view of the world. At one point, Thilo introduces the concept of transparent looking to Wojnicz as they study a painting together: “‘It goes beyond the detail, it leads, as Herr August would say, to the foundations of the view in question, to the basic idea, leaving out minor features that continually scatter a person’s mind and vision. If you look this way…you would see something else entirely.’” (177) This conversation is a turning point for the young Wojnicz and serves as one of his first moments of self-realization.

The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story is thus a book for those that know their history, enjoy looking for details, and making connections. It is an excellent overview of the precipice of violence that Europe found itself on in 1913, the philosophies and sciences that were disrupting society at the time, and the still-rampant misogyny that dominated the social landscape. This is an excellent book to reread and discuss with others. Like Thilo’s painting, each time you look at this text, something new will present itself.

Olga Tokarczuk is the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature and International Booker Prize and is one of Poland’s most well-renowned contemporary authors. Her other works translated to English include: Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, Flights, The Books of Jacob, Primeval and other times, and House of Day, House of Night. The Empusium, her most recent publication, is an excellent and atmospheric read. Wojnicz, despite his passivity and anxiety, is a complex and brave character whom readers cannot help but root for.

You’ll Also Love

Book Review of Lavash at First Sight

Taleen Voskuni’s Lavash at First Sight (2024) is a funny and lighthearted sapphic romance about two Armenian-American women roped into promoting their respective Armenian food…

Book Review of The Right to be Helped: Deviance, Entitlement, and the Soviet Moral Order

Maria Cristina Galmarini-Kabala. The Right to be Helped: Deviance, Entitlement, and the Soviet Moral Order. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2016. 316 pp., $25.99…

Book Review of The Politics of Culture in Soviet Azerbaijan, 1920-1940

Audrey, Altstadt. The Politics of Culture in Soviet Azerbaijan, 1920-1940. Routledge, London and New York, 2016. 234pp, $65pb. ISBN 9781138639003. “We are undertaking the…

Understanding Moscow through Literature, History, and Film

Fyodor Tyutchev once said that “Russia cannot be known by the mind” – but perhaps Moscow can be known through literature and historical surveys? A…

The Present Is History: A Journey to Newly-Independent Kyrgyzstan

Eugene Huskey is one of America’s foremost experts on modern Kyrgyzstan. The following text recounts his first trip to Kyrgyzstan in June of 1992, just…