Bishkek is capital of one of Central Asia’s poorest countries. However, it is also a modern, dynamic, and constantly evolving city with a rich history dating back to the 6th century.

Bishkek is known for many things. It is Kyrgyzstan’s political center, where its 2011 presidential election marked the first peaceful transfer of presidential power in post-Soviet Central Asia. It is Central Asia’s greenest city, with a rich biodiversity in its tree-lined streets and many parks. It is a regional strategic center of international importance, home to the Transit Center at Manas International Airport, a logistical hub for the coalition effort in Afghanistan. It is also Kyrgyzstan’s financial center, home to 21 commercial banks and a large number of industrial plants. Bishkek is much more than just a “place below the mountains” – as one of its possible namesakes proclaims.

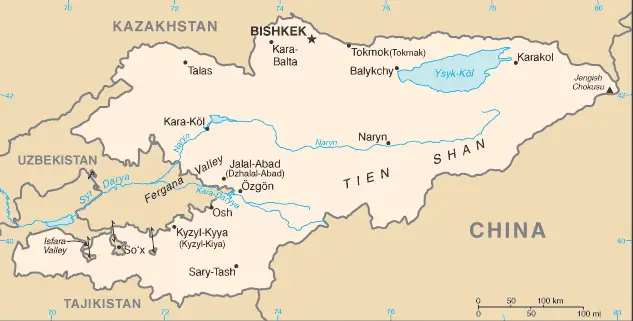

Major locations in Kyrgyzstan (including Bishkek). The large lake in the northeast is Lake Issyk Kul, a massive body of salt water and popular tourist site

Location

Bishkek is the capital of Kyrgyz Republic and administrative center of the Chui region. It is situated in the central part of the Chui Valley at the foot of the Kyrgyz range of the Ala-Too Mountains. While this range stretches up to maximum height of nearly 16,000 feet (higher than the Canadian Rockies), Bishkek sits at a relatively moderate altitude of about 2600 feet (approximately the same altitude of Boise, Idaho).

To the north are the Jalanash hills in Kazakhstan, which protect the city from extreme summer and winter temperatures. To the south are the Tien Shan Mountains. There are two rivers that flow through the city – the Alamedin and the Ala-Archa, both tributaries of the River Chu.

The top soil run off from the surrounding mountains, coupled with the relatively moderate climate and river systems has made the Chui Valley an important regional agricultural center. The surrounding extreme differentials in elevation also help create breathtaking natural views as well as phenomenal opportunities for horse trekking in the summer and for winter sports in the winter.

History

The history of Bishkek dates back to the 6th century, starting with a Sogdian settlement called “Jul” which occupied the area of Bishkek currently located between the streets of Orozbekova, Leningradskaya, and Kirova. While it is known that Jul was a cosmopolitain center populated by Zoroastrians, Buddhists, Nestorians, and Manichean Christians, little is known about Jul today, for the Mongols and Tartars under Genghis Khan destroyed it in the 12th century. But Jul’s diverse population may well help explain Bishkek’s tradition of ethnic and religious tolerance. After Jul was destroyed, the area remained lightly populated, mostly by those serving the travelers that came through along the Great Silk Road, one route of which passed through the area.

In 1825, a fortification was built under the Uzbek Khanate of Kokhand, as part of a greater campaign to conquer the fertile Chui Valley. The mud fortification near modern Bishkek would become one of thirty-five in the region.

Muslim worshipers pray outside Bishkek’s Central Mosque. Photo from Radio Azattyk.

Under the Khan of Kokhand, the Kyrgyz were first exposed to Islam. The spread of Islam in this northern region, however, remained limited. The Kyrgyz, set in their nomadic ways and shamanistic beliefs, continued to worship elements such as the sky, earth, sun, water, and fire, and natural objects like rocks and trees well into the early 19th century. Those who did convert to Islam often chose the Sufi sect – and only because the Sufi propagators allowed them to continue some of their shamanistic practices.

By the mid-19th century, the Kyrgyz rebelled against the Kokhand Khanate and appealed to Tsarist Russia for help. In response, in 1862, the Russians laid siege to the mud fort, and in 1876 destroyed the Kokhand Khanate. A year later, the Russians made this region their protectorate and renamed the city “Pishpek,” a word actually taken from the Kazakh language. While the Russians experienced residual popular resistance from the various Kyrgyz tribes, a negotiated settlement with the “Kyrgyz Queen,” one of the leaders of the Kyrgyz tribes, stabilized Russia’s hold over the area.

Because Pishpek was at the crossroads of several caravan routes and served as a junction for several major roads that lead in all directions, Pishpek was developed into a regional administrative center by the tsarist government. Under the leadership of Governor-General G. Kolpakovsky, the city was repopulated with Russian and Ukrainian settlers, and constructed to become Kyrgyzstan’s first European-type city. The Russian Army Engineers gave Pishpek a rectangular grid pattern of streets and parks, a design deemed “more progressive” in comparison to the medieval layouts of most cities in Central Asia. Pishpek was also lined and dotted with greenery, with the plantings of places like the Elm Grove, the Oak Park, the Erkindik Boulevard, and the City Park. Today these remain not only some of Bishkek’s favorite resting places, but the reason Bishkek is known as the greenest city in Central Asia, with more trees per capita than any other.

Alim Khan was the last Emir of Bukhara, a state which would border southern Kyrgyzstan if it still existed. The Emir slaughtered the Soviet delegation (and many of their local supporters) that asked for his surrender and sent the Soviet army in retreat. While not Kyrgyz, he is an example of the powerful resistence that Frunze encountered in Central Asia. Photo: 1911, Prokudin-Gorskii

With the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917, Pishpek became the center of revolutionary struggle. During the Civil War, Bolsheviks fought against the so-called basmachis – militia groups led by ambitious commanders, tribal leaders, and sometimes simply adventurers. Soviet propaganda depicted the basmachis as Islamic fanatics, or gangs with counter-revolutionary, Pan-Islamic and Pan-Turkic tendencies, but the basmachis were, in fact, an “all-people” resistance movement, made up of many languages, ethnicities, and religions. And for a while at least, the basmachis put up a good fight, especially those in southern Kyrgyzstan.

But when the capable and brutal Bolshevik general, Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze, a native of Pishpek, was sent to lead the Red Army in Central Asia, the basmachis lost strength. They were defeated in the 1920s. After that, there was no serious challenge to Soviet power in Kyrgyzstan until the 1980s.

As a result of General Frunze’s campaign, Soviet power in Pishpek was established in 1918. In 1924, Pishpek became the administrative and political center of the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region. Two years later, it was renamed in the general’s honor as “Frunze.” Today, a statue of him opposite the Bishkek railway museum and a museum dedicated to him still stand. This legacy is also why Bishkek’s airport still carries the designation code “FRU.”

In the 1920s, the city of Frunze began to seriously industrialize, mostly with factories that took advantage of the surrounding agriculture and forests. Leather factories, cloth mills, knitted goods, furniture factories, and other workshops were constructed. But Frunze acquired the status of an important city only after World War II. This was because, as a city far from any active fronts that did not see fighting during WWII, key factories, highly qualified specialists, and non-military enterprises were moved to Frunze after being evacuated from regions threatened by the advancing German troops. Thus, during World War Two, Bishkek developed an extensive machine-building and metalworking industry. Today, Bishkek’s factories produce roughly half of Kyrgyzstan’s industrial output.

During the Soviet era, Frunze also developed architecturally. The Soviets put their own stamp on their capital’s skyline, building numerous apartment blocks and public buildings along the city’s grid. Stylistically, the Soviets combined elements of Central Asian and classical architecture – called the “provincial modern” style – which survives today in buildings like the Bishkek Railway Station and the Administrative Building. During the 1970s and 1980s, another massive building program saw the constructino of the white marble-faced government and public buildings that largely symbolize the city today. Of course, Bishkek continues to grow and develop. However, there are some, like Jack Losh of Time Magazine in 2010, who still consider Bishkek “a time capsule of Soviet-era architecture.

Relief map of Kyrgyzstan showing the country’s almost entirely mountainous territory.

Bishkek’s Namesake

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the post-Soviet government promptly renamed Frunze “Bishkek” – the Kyrgyz variant of the Kazakh “Pishpek” – a symbolic tribute to the revival of Kyrgyz identity. However, the origin of the name, while inarguable Kyrgyz, is debated.

While the Russians were the first to name the mud fort “Pishpek,” there are competing theories – and legends – about why this word was chosen, and what it really means.

Some say that “Pishpek” was chosen because of a legend of the Khan of Kokhand’s wife, who once had a beautiful, precious, jewel-studded churn. One day, she lost it. Angry, the Khan sent 40 men to find it, but they could not. Rather than return in shame, they settled to a life in exile and named their encampment after the object of their search.

There is another legend that “Bishkek” was so named because there were five knights who fought over the beautiful land where it now stands. In Kyrgyz, “besh” means “five,” and “kek” means “chief.”

Still another theory states that the area was long known as “peshagakh,” which means “place below the mountains” in ancient Sogdian. Bishkek, it is argued, is a linguistic corruption of the term.

A Multi-Ethnic City

Whatever its namesake, today, Bishkek’s population accounts for one-fifth of the country’s 5.5 million people. Home to a diverse 82 ethnicities, Bishkek has a Kyrgyz majority, with significant Russian and Uzbeks minorities. Bishkek is also the only city in Kyrgyzstan where the Christian population is more prominent than the Muslim population. The three major religions in Bishkek today are Russian Orthodox, Roman Catholicism, and Islam.

Bishkek tolerates Russian political organizations more so than its neighbors, registering at least some Cossack organizations and the Movement for Brotherhood and Union, which is clearly committed to the restoration of some form of reintegration with Russia. The Russian language is still widely spoken and Russian-language publications and TV channels carry more weight than their Kyrgyz counterparts, with the most popular being Channel One and Russia Channel, which are also Russia’s most popular channels and which report on foreign events at length. This is one reason why the majority of the Kyrgyz populace often see eye-to-eye with the views of the majority of Russian citizens, especially on issues of international importance.

Russian is an official state language of Kyrgyzstan, sharing that status with Kyrgyz. Former Kyrgyz President Roza Otunbayeva, however, says that Kyrgyz maintains an “inferior position.” Some efforts are being made to raise the status of Kyrgyz, but others argue that this could come at the expense of Russian, a lingua franca of government and business in Central Asia that is valuable to resource-poor Kyrgyzstan in maintaining regional relations and attracting foreign investment from Russia.

Although southern Kyrgyzstan has seen violence related to ethnic tensions and Islamic extremism, tourists and travelers to Bishkek generally report feeling safe. Overall, violence is rare. When there are instances of Islamic extremism – in Bishkek or in southern Kyrgyzstan – the Kyrgyz government acts quickly to address it. This has been the case especially after the September 11, 2011 attacks in New York City, and Central Asian governments became sensitive to the United States government’s commitment against Islamic terrorism. In 2010 the Kyrgyz government blamed Islamic extremists for a series of “terrorist” acts in Bishkek including a home invasion and two bombings.

Political Center

A protest on Ala-Too square in central Bishkek in April 2006. Anti-government protestors eventually toppled the government in 2010. Picture by Michael Coffey, an SRAS student who was on the ground at the time.

As the political center of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek has witnessed its share of political unrest and demonstrations. The most recent example is the 2010 Tulip Revolution that overthrew the Akayev government. Up to 20,000 protestors assembled in the central square of Bishkek, marched towards the presidential administration building (known as “The White House”), and overpowered the contingent of riot police posted along the perimeter of the building. It resulted in a new government on December 17, 2010, competitive elections a year later, and the swearing-in of President Atambayev in December 1, 2011. Atambayev’s presidential win became known as the first peaceful and democratic transfer of power in Central Asia.

Today, the political situation in Bishkek is considered “relatively stable” by the US Department of State. So while Bishkek is mostly spared from the inter-ethnic violence of southern Kyrgyzstan, many in the capital have grown used to the political tensions of their turbulent democracy.

Conclusion

Bishkek is a fascinating place with a rich and colorful blend of Central Asian, Imperial Russian, and Soviet heritage, and now Western infuence. It has a proud history that is honored through its unique architecture, city design, and people. At the same time, it has a modern spirit, as demonstrated by its efforts to redefine and reinvent itself.