Transdnestria, or The Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (which is the full name its government uses) lies mostly within in a single narrow valley on the east bank of the Dniester River. Internationally considered part of Moldova, Transdnestria is a de facto state, having declared its independence in 1990 and successfully defended it in a brief war with Moldova in 1992. Despite numerous and ongoing negotiations between Moldova, Transdnestria, and third parties such as Russia, Ukraine, and the US, little progress has been made on a settlement between the two parties, and at present Transdnestria remains isolated and unrecognized.

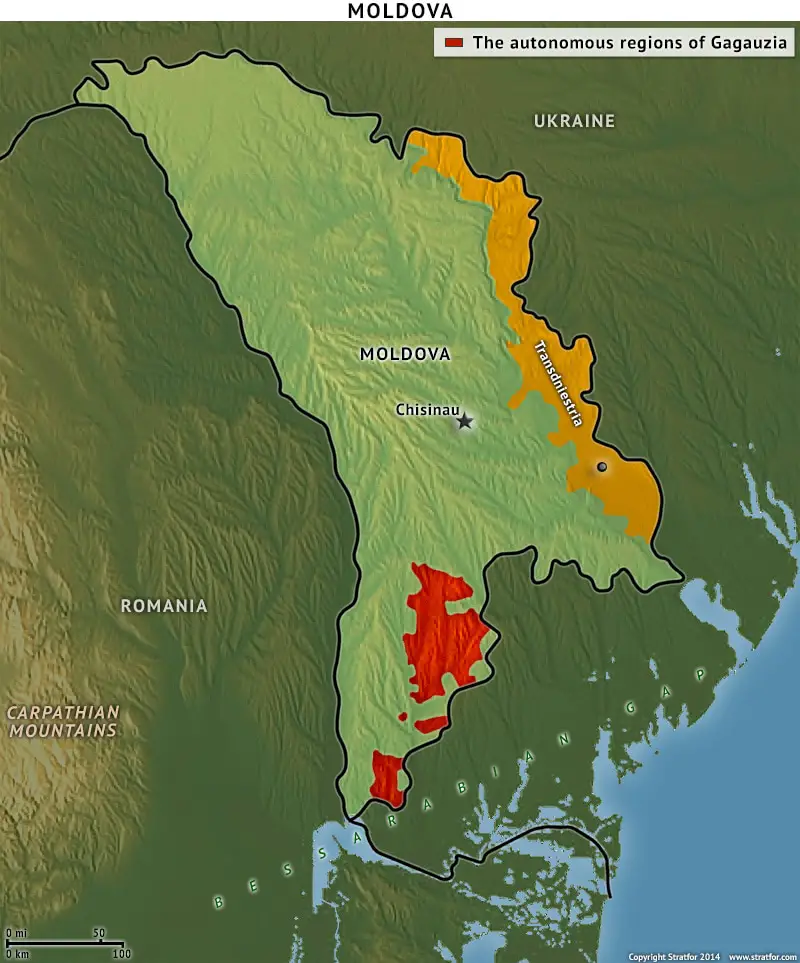

A map showing Moldova and the disputed area of Transdnestria (in yellow) and the formerly disputed region of Gagauzia (in red), a region that had also once sought independence but which instead negotiated a status of “autonomous region” within the Moldovan state. Map from Stratfor.

Transdnestrian Geography

The republic of Transdnestria is just over 60 miles long and at points less than 2.5 miles wide, encompassing little more than short strip of land on the eastern bank of the Dniester River. In total, it encompasses 1607 square miles which is about 1.6 times the size of Luxemburg and about 100 square miles smaller than Anchorage, Alaska.

The state is broken into several distinct areas where its territory bulges outwards to incorporate larger towns, the largest of these being Tiraspol, the capital. Towards the southern tip of Transdnestria, Tiraspol is a city of 160,000 people, the largest town in Transdnestria and what Moldova claims as its second largest.

Just to the West of Tiraspol across the Dniester River is the city of Bender (population 94,000), an old border fortress of the Ottoman Empire which still retains remnants of its old city walls. Further north, Tiraspol’s third major center is the town of Rybnitsa (populations 57,000), home to a major steel mill and other working industrial plants which produce most of Transdnestria’s limited exports. Outside of these centers, Transdnestria remains largely pastoral, with villages and small towns scattered throughout the narrow Dniester river valley.

Transdnestrian Separatism and Its Origins

As many of the towns in Transdnestria first came to prominence as border posts during the Russian Empire, the region has, since the beginning of the 19th century, been home to large groups of Russians and Ukrainians in addition to Moldovans. Russians and Ukrainians have long been the predominant ethnic groups in the Russian population and army.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian and Ukrainian groups together outnumbered Moldovans in most of Transdnestria’s urban areas and were sizable minority elsewhere. As the Russian Empire fell, the region was incorporated into the Soviet Union as part of the Moldavian SSR, a region which, at that time, did not actually include much of what is modern-day Moldova, as the Bessarabia region had then joined with Romania.

While Transdnestria briefly fell to the Nazis during the Second World War, in 1945 it was reincorporated into the Soviet Union as part of a newly-enlarged Moldavian SSR, together with the Bessarabia, taken from Romania which had sided with Germany.

While this meant that Russian and Ukrainian populations became minorities in a primarily Moldovan SSR, Slavs retained a privileged status in the region, as Moldovans, which are ethnically related to the Romanians, were considered to have sided with the Nazis and were, in many cases, targeted for reprisals by the Soviets. The Moldovan language was shifted to the Cyrillic alphabet, and Russian was made the official language of the region.

Under Soviet rule, the Russian and Ukrainian populations of Transdnestria, as well as Moldova as a whole, continued to grow and workers were brought in to repopulate the war-torn region and build new infrastructure in the towns of the Dniester Valley. In 1989, for example, over half of the population of Transdnestria was Russian or Ukrainian.

A short documentary shot by Miles Atkinson, an SRAS student.

Under Gorbachev, Moldovans began to voice their long-suppressed nationalism, and the Moldovan SSR took actions such as declaring that the Moldovan language would again be written with Latin script and would be the official state language. In part reacting against this, in 1990 Transdnestria declared its independence from Moldova as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian SSR, an autonomous unit within the USSR.

This independence movement was largely lead by Igor Smirnov, a Ukrainian-born electronics factory director who had turned to politics during the major strikes in Tiraspol to protest the establishment of Moldovan as the state’s only official language. While Mikhail Gorbachev dismissed the Pridnestrovian SSR as lacking any legal authority, no action was taken against the new state, and Smirnov was shortly thereafter elected the first president of Transdnestria.

Moldova was initially distracted from Transdnestria by its own independence movement, and seceded from the Soviet Union in 1991 to become the Republic of Moldova. However, shortly after declaring its independence, Moldova attempted to reassert its authority in Transdnestria. In 1992, as Moldovan police and military units attempted to enter Transdnestria, armed conflict broke out. A short war began in June of 1992, when the Moldovan military crossed the border and entered the city of Bender, pushing out the disorganized Transdnestrian defense forces. However, the former Soviet 14th Guards Army (at that time recently incorporated into the new Ukrainian Armed Forces), which happened to be stationed nearby across the Ukrainian border, at this point decided to come to the aid of the Transdnestrian forces and counterattacked, pushing the Moldovans back across the border and effectively ending the war. A ceasefire was declared on July 21st 1992.

Tiraspol’s central square, featuring a large statue of Lenin in front of the main government building. Photo from Balcanicaucaso.org.

Since the ceasefire, little has changed in Transdnestria’s situation. Extensive negotiations have been conducted, both directly between Moldova and Transdnestria and with various partners such as Russia, Ukraine, Romania, the EU, and the OSCE, yet neither side has been prepared to compromise to the extent necessary to reach a settlement.

Transdnestria suffers considerably more than Moldova from this impasse. Transdnestria is wholly unrecognized by any other nation, which means it has no visa regimes, no official border entry points, not customs controls, cannot officially attract foreign investment, and a range of other issues. It particularly has difficulty in exporting and importing goods – which has resulting in economic stagnation and frequent shortages.

While Transdnestria has at times seemed receptive to reintegration with Moldova, as a prerequisite to this it has insisted on receiving grossly disproportionate representation in government of a future Moldovan federal state, something which Moldova has no intention of allowing. There was also some hope that the pro-Russian communist government elected in Moldova in the early 2000s would be able to bridge the gap between the two groups, but, after a brief rapprochement, negotiations once more collapsed, and the communists have since been voted out.

For the last several years, Moldova has been in political crisis, as its electorate is roughly divided between Russian-leaning communists and European-leaning liberals and thus has, under it’s arduous constitutional requirements, been unable to elect a president. Thus, most major issues, including Transdnestria, have been long shelved.

However, as of March of 2012, both Moldova and Transdnestria have new presidents, leading to some hope that perhaps the peace negotiations may begin to move forward again.

Current Politics of Transdnestria

Following the successful war of independence, Transdnestria held its first elections in 1991, with Igor Smirnov, the leader of the former communist government, handily winning with 64% of the vote against Grigorii Marakutsa, another former Communist bureaucrat. Following his first electoral victory, Smirnov established himself as the only political power in Transdnestria, and proceeded to win three successive elections in 1996, 2001, and 2006, each time with greater margins of victory. This culminated in the election of 2006 when Smirnov won with over 82% of the vote.

A campaign poster from the Transdnestrian presidential race from the underdog candidate that won the race, Evgenii Shevchuk.

Overall, politics during the Smirnov era were characterized by widespread corruption and these elections were condemned by international observers as wholly undemocratic exercises. In the 2001 election, Smirnov reportedly took 103% of the vote in the Kamenka region in the north. Ballot stuffing, voter fraud, and voter intimidation were widely practiced, and a number of opposition candidates were not allowed to appear on the ballot. The country also lacks any major media outlets receiving most of its news from Russian and Ukrainian media sources, which offer little commentary on Transdnestrian domestic events.

Transdnestria was largely stagnant under Smirnov, who made no real progress in gaining international recognition for Transdnestria or towards turning the region into a viably independent state. In addition to difficulties with import/exports, shortages of goods, and the near impossibility of foreign investment, unemployment remained extremely high and shortages of staple goods were frequent.

Gradually, public opinion turned against Smirnov, and, following the 2001 election, even his own political allies began to turn against their aging leader. In 2005, the opposition party Renewal managed to win a commanding majority in the parliament, and in the 2011 presidential election, Smirnov placed third, behind opposition politicians Evgenii Shevchuk and Anatolii Kaminski.

Smirnov seemed to have been caught by surprise by this upset, and demanded the election results be discarded due to electoral fraud. However, the election results were upheld by the Transdnestrian courts, and Smirnov peacefully ended his 15-year rule.

Following Smirnov’s defeat, a runoff election was held between Shevchuk and Kaminski. While both of these politicians were from the Renewal party, Kaminiski was supported by the Russian government, while Shevchuk was believed to have more western leanings. Shevchuk, a liberal businessman, easily won with over 70% of the vote, becoming Transdnestria’s second president.

Kaminskii continues to hold the party leadership, however, and has already been sent on diplomatic missions, indicating that he will have a role in the new administration. So far, Shevchuk’s government has brought few palpable changes, though there are hopes that he may yet be able to bring Transdnestria out of its doldrums and effect a solution to at least some of its myriad problems.

International Climate and the Future of Transdnestria

Transdnestria has had few allies abroad. While it won its independence with the support of the Ukrainian military and while Ukraine has occasionally moved to ease trade with Transdnestria, Ukraine has never recognized Transdnestria as an independent state. Neither has Russia, whose peacekeepers have been stationed in the country to help maintain the ceasefire since it was declared and which has been accused of actively influencing Transdnestria’s internal politics.

The last serious attempt at reunification was with the Kozak Memorandum in 2003. The memorandum was named for the Russian politician, Dmitri Kozak, who championed it, particularly when it was debated within the OSCE. It was ultimately rejected by Moldova as it would have allowed Russian peacekeepers to be stationed in Transdnestria (and thus on Moldovan soil) until 2020. The memorandum also envisioned an asymmetrical federal structure in which would have given Transdnestria 35% of the structure’s seats (and the ability to block constructional changes), despite having only 14% of the total population of the reunited country. This disproportionate representation and the subsequent ability to disproportionately block policy formation is another likely reason that the Moldovans refused to accept the measure.

It seems increasingly unlikely that Transdnestria could be reunited with Moldova. However, without international recognition, Transdnestria will always struggle economically.

While the negotiating mechanism was enlarged in 2005 to include the US and OSCE, this does not seem to have resulted any change in status. As relations deteriorate between Russia and the West in the wake of Putin’s reelection, it seems likely that Transdnestria will remain isolated and unrecognized for the foreseeable future, a quasi-state on the edge of Europe.