What climate change and arctic development means for Russia, the environment, and the international community.

The Arctic region is a vast area whose economic potential, through climate change and advanced technology, is becoming accessible for the first time in history. This potential includes hydrocarbon resources as well as shipping lines, fishing rights, and metal deposits. Developing the Arctic will require massive investment – particularly into transportation, extraction, and governance infrastructure. Yet beyond establishing infrastructure, Arctic states must also consider the various environmental and diplomatic risks associated with such development.

At present, Russia has already begun developing infrastructure for its substantial Arctic territories, integrating them into its long-term development plans. Congruent with Russia’s development imperatives, these moves have given Russia an early lead in the Arctic territories. They have also been met with some alarm from other states.

This article will focus on the economic and military aspects of Russia’s development of its coastal and oceanic Arctic regions and the issues of international concern that arise because of them. Overall however, despite wider, growing geopolitical tensions, international cooperation is currently the norm in the Arctic, notably in resolving and expanding territorial disputes and in maintaining environmental stability there.

Problem One: Defining the Arctic

The Arctic spans some 14.5 million square kilometers, including the North Pole, Arctic Ocean, and extensive inland areas. While the North Pole and a substantial portion of the Arctic Ocean remain unclaimed by any country, Canada, Norway, Russia, Denmark (via Greenland), and the United States all have territorial claims within the Arctic region.

Arctic territorial claims are guided by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which spells out two definitions which determined these claims.

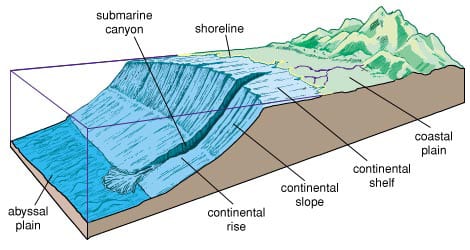

From shoreline to abyssal plain: image explaining the continental shelf. For more info, check out this video.

“Territorial waters” refers to the seabed, water, and airspace extending 12 nautical miles from the baseline (coast) and is regarded as sovereign territory. Here, foreign ships can only pass through territorial waters for the purpose of transporting civilians or to pass through a strait.

“Exclusive Economic Zones” (EEZ), the second concept, extend 200 nautical miles from the coast and grant each state the sovereign right to explore and use all economic resources below the surface of the water (in colloquial usage, the continental shelf), including those for energy production. However, surface waters in EEZ’s remain international water.

Map of the Arctic showing the July Isotherm line (orange), the Arctic tree line (green) and the Arctic circle (red).

States also have the right to resources on or below their continental shelf (seabed) up to 350 nautical miles beyond the coast; however, the legal definition is not to be confused with the geological definition of the term, which also includes the continental slope and continental rise. (Insert picture showing the difference) Any resources above the shelf, including living organisms, cannot be claimed by a nation. These oceanic Arctic regions are referred to as the “high seas,” or international waters.

For inland Arctic territory, three major definitions delineate these Arctic regions, including the northern limit of stands of trees on land (the treeline) and the line of the average July temperature of -10 degrees Celsius. However, these lines vary depending on changing environmental conditions, and are therefore used mainly for scientific purposes. Instead, the most consistent and widely used definition is the Arctic Circle line of latitude, located at 66 degrees 33 minutes North. While inland regions make up a substantial portion of delineated Arctic territories (as shown in the map above) due to pre-established national boundaries, inland disputes rarely drive Arctic territorial conflict.

Most international contestation remains on the coastal side of Arctic territorial distribution, where definitions cross into murky water and create potential for conflict, as exploration and development increasingly create new economic opportunities.

Problem Two: Developing Arctic Infrastructure

Map showing the various Arctic oil and natural gas provinces. Originally featured on Geology.com.

Oceanic Arctic territory plays a highly strategic role within Russia’s developmental goals. The region offers opportunities to seek Asian investment, look south and east for new markets, improve domestic transport, and boost internal shipbuilding, resource extraction, and other industries.

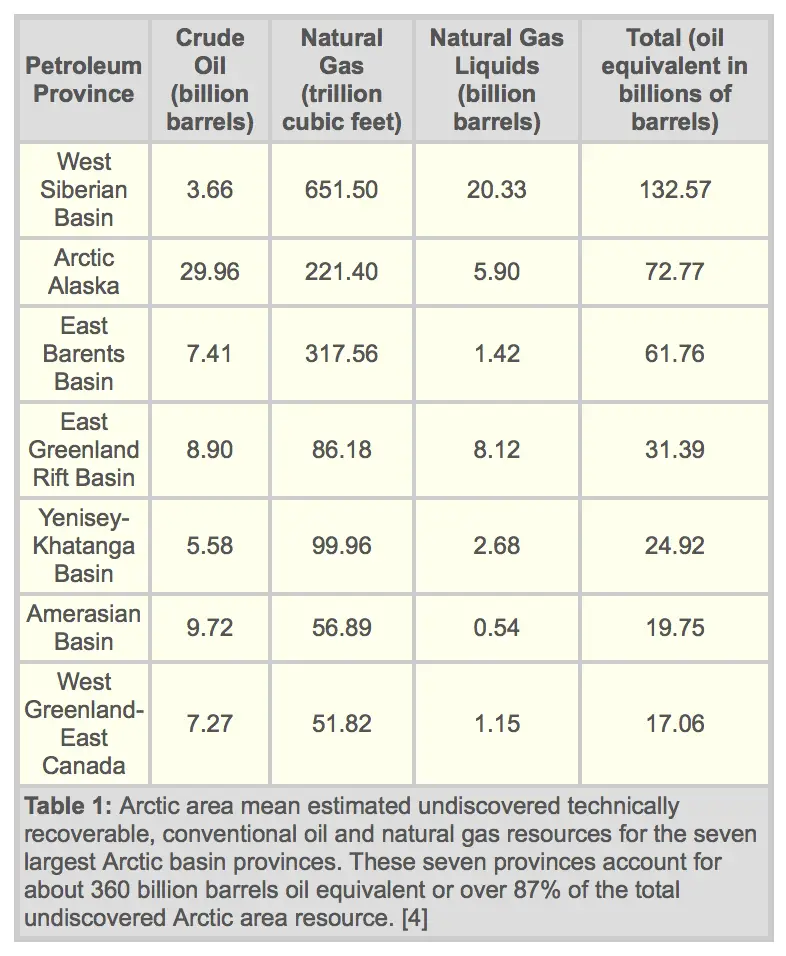

Beginning with resources, the Arctic is home to an estimated 412 billion barrels of recoverable and conventional oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids. Approximately a third of the territory consists of continental shelves which have been very lightly explored. 87% of these resources are thought to lie in seven Arctic basin provinces, as shown in the table below.

Table outlining the total crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids oil equivalent in billions of barrels. (Geology.com)

Historically, challenging arctic conditions presented great risk to developing extraction infrastructure. However, with global warming affecting the arctic disproportionately to the rest of the world, and with sea ice covers and flows subsiding by as much as 30% over the last thirty years, these resources are now becoming more accessible.

For Russia, oil and gas underpin the nation’s economy. In 2005, revenue from oil and gas made up 18.6% of Russia’s industrial profit share. That figure rose to 22.7% by 2013. While Russia is attempting to diversify its industries, maintaining oil and gas production is an economic imperative for national stability. Clearly, the Arctic is a promising economic region.

At the end of August 2017, Prime Minister Dimtry Medvedev stated that $2.787 billion will be spent on developing the Arctic continental shelf and coastal areas through 2025. Russia’s giant state corporations, Gazprom and Rosneft, are also visibly active in the region. In 2013, for example, Gazprom began annual extraction of around 40.3 million barrels from the Prirazlomnoye Oil Field in the Pechora Sea. In April 2017, Rosneft began drilling in the Laptev Sea for some 586.4 million extractable barrels of high quality (light and low-sulphur) oil. Rosneft has also invested in 28 other Arctic drilling licenses and plans to develop deposits in the Barents Sea and Kara Sea within the next two years.

The NSR makes up one of the main shipping routes existing in the Arctic region, alongside the Northwest Passage. Traversing from West to East, the Northern Sea Route runs along the Russian Arctic coast from the Kara Sea, along Siberia, and to the Bering Strait, marking the Russian portion of the Northeast Passage.

Beyond oil and gas, however, the Arctic coast is also home to the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which Russia hopes will one day be used to ship hydrocarbons and other goods to and between Asia and Europe. The country also foresees that the increased sea access will help the development of Russian regions further inland.

Since its inception, Russia’s lack of seaports have limited the country’s access to international trade and hampered internal development of its vast territories. Wars were fought to gain access to the Baltic Sea and Pacific, but most of Russia’s ports are now operating at capacity. Yet, without access to the Arctic, they are unable to process Russia’s growing agricultural production and export potential.

The Soviets first drew up serious plans to develop Northern Sea Route but only today are plans being realized.

Yamal and Norilsk are particularly promising hubs along the NSR. Yamal, rich in oil and gas, opened a liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility in 2013. The facility will rely heavily on Arctic shipping lines to send over 16.5 million metric tons of LNG per year to Europe and Asia.

Norilsk hosts some of the world’s largest nickel, copper, and palladium deposits, all of which are used in modern electronics. MMC Norilsk Nickel, the city’s principal mining operator, produces almost 300 thousand metric tons of nickel annually. Without a road or railroad network connecting Norilsk to the rest of Russia, the city relies entirely on Arctic sea routes to transport freight to market.

Russia also hopes to develop shipbuilding in its Far East regions, where declining population levels and a struggling economy create what many consider to be national security concerns. The Zvezda facility, recently opened in the Primorye Territory, will produce supply ships, ice-class tankers, gas carriers, and drilling platforms. The facility is near Asian customers who Russia hopes will use the NSR to ship freight, and it is also receiving investments from major oil and gas companies who hope to develop Arctic energy deposits. Zvezda itself is a consortium of Rosneftegaz, Rosneft, and Gazprombank.

Even more, Russia hopes that such facilities will spur other domestic industries. Shipyards such as Zvezda, for instance, are projected to require over 300,000 tons of rolled steel per year, representing a potential boon for domestic metal producers. Russian President Vladimir Putin has recently proposed that only Russian-flagged ships be allowed through the NSR. Ostensibly, this is a security measure, but also represents additional impetus for domestic ship production and the use of domestic shipping infrastructure to fully realize the economic potential of the route.

A better-developed NSR will also mean shorter shipping distances to ports for Russia’s northern territories, meaning resources extracted and goods produced there will be cheaper, and thus, more competitive on international markets.

With oil and gas, metal production, shipbuilding, domestic transport, and greater access to European and Asian markets, Russia’s Arctic waters and continental shelf clearly present acute economic potential.

Problem Three: Securing the Arctic

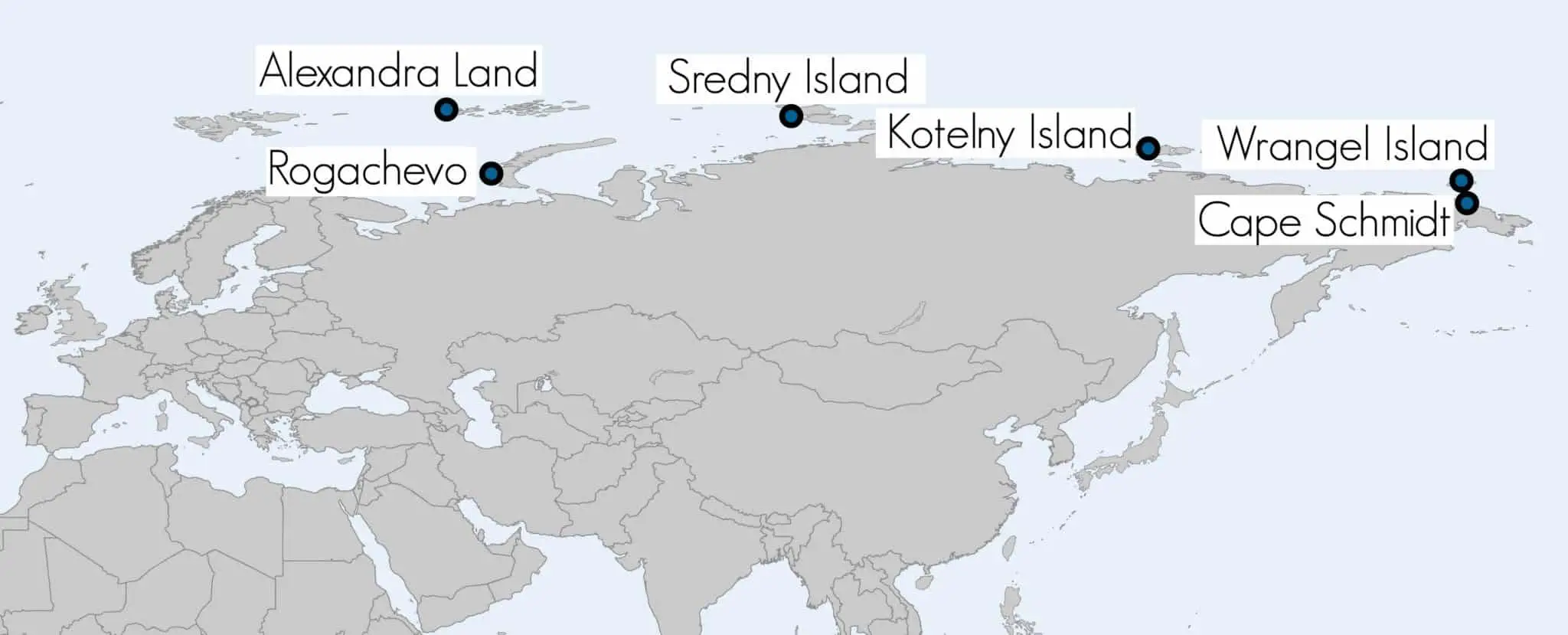

With a great deal of economic potential on the line, since 2012, Russia has rapidly developed its military presence in the Arctic, with a focus on air and maritime technologies. In total, Russia has added four new arctic brigade combat teams, fourteen operational airfields, sixteen deepwater ports, and 40 icebreakers, with an additional eleven in development. For comparison, the United States only has one working ice-breaker.

Russia has constructed 6 military bases along the Northern Sea Route. (Image Source: High North News)

The Russian Ministry of Defense’s newest military base: the Arctic Shamrock, on the large island of Alexandra Land.

The Arctic Shamrock and Northern Clover military bases (Alexandra Land and Kotelny Island, respectively) are designed to provide regional air defense and have pushed Russia’s military presence further north than any other country, giving Russia a distinct military advantage in the area. The Arctic Shamrock is, in fact, the world’s northernmost permanent building. Critics argue that this development is aggressive, as many regard the Arctic as one of Russia’s most stable and easily defendable borders and thus, that its military presence in the region should be minimal.

Russia does have need for a military presence in the area, however, given the enormous economic potential presented by Arctic access, coupled with the difficulty in policing economic infrastructure in sparsely populated areas and maritime routes. The African coast, for instance, has for centuries been the site of valuable trade routes, but routes that have crossed international waters or the coast lines of weak states. The lack of policing efforts has allowed pirate groups to feed on the trade routes even up to the present day. While the concept of “arctic pirates” may seem laughable to some, it is true that rare animals, mammoth tusks and other archeological relics, and even lumber are currently pirated in Russia’s inland arctic areas and sold illicitly on international markets. Imagining that such criminal groups could find ways to extend their activities to take advantage of growing international shipping lines to the north is not difficult. Russia hopes to avoid this and offer a more secure and thus more competitive alternative, which cannot be done without a military presence.

Thus, while there have been protests from many in the international community, Russia argues, that its military buildup is essential to its economic development, national security initiatives, and the security of its trading partners. At minimum, Russia can argue, the buildup will better secure what is internationally recognized as Russian territory.

Problem Four: Environmental Impacts of Development

While climate change is helping to fuel Russia’s moves in the Arctic, Russia’s development of the region will continue contributing to rising temperatures. This, and the fact that Arctic development presents specific environmental risks, makes Russia’s activities in the region of relevance within international environmental discussions.

The greatest environmental threat to the region stems from the extraction and transportation of fossil fuels. While oil and chemical spills are likely to occur in any region containing oil and gas reserves, when such spills occur in the Arctic, they are particularly dangerous incidents.

For example, because the Arctic drilling season is typically limited to a few months during the summer, companies have a limited timeframe to cap leaking oil/gas wells or successfully drill relief wells before winter sea ice returns. Oil spills are also difficult to clean up and contain, as oil will become trapped under large blocks of ice and travel large distances under ice flows. Extreme weather conditions, short days, lack of search and rescue stations, also amplify the danger of such events.

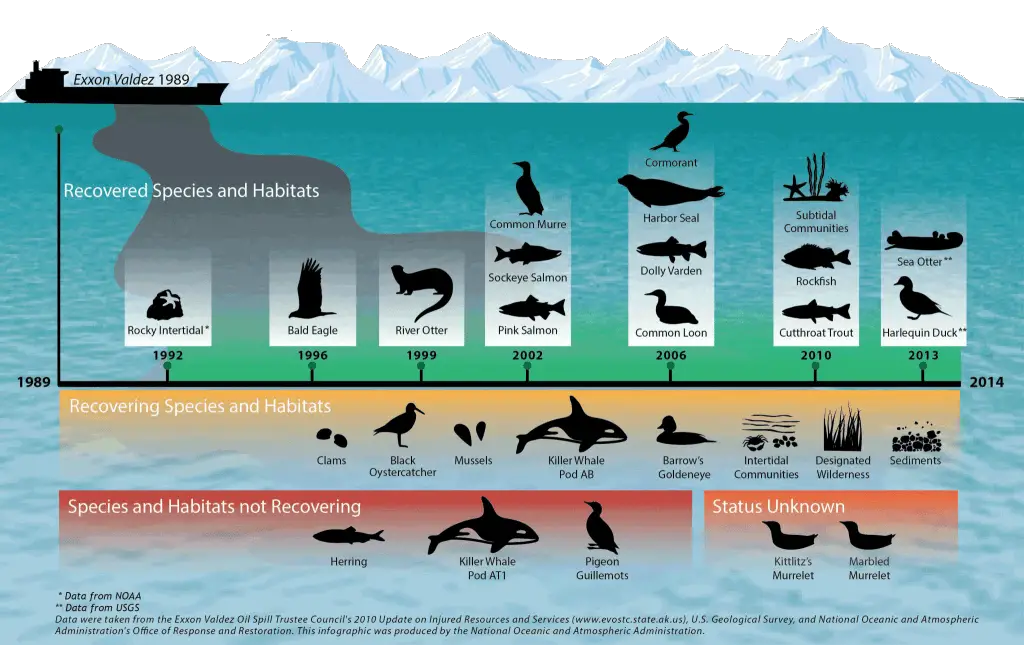

While over time, various species impacted by the Exxon Valdez oil spill have recovered, over 25 years later, several species are still recovering, or have not yet recovered at all. Image produced by U.S. Department of Commerce and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The fields which are currently under development reside in areas still affected by serious levels of ice. So, while icebreakers and advanced equipment are allowing for production, risks are still present. Yet, measuring such risks is also difficult because Arctic oil and gas drilling has only recently begun, and only one major spill has been reported. This was the 1989 Exxon Valdez incident that spilled 11 million gallons of oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound, where only 7% of spilled oil was recovered. While the same mistakes may not be made by Russian companies, the lack of experience in Arctic drilling along with successful clean-up procedures inherently brings risk to the industry.

Arctic shipping also poses environmental threats. For example, black carbon (soot) is a common pollutant produced by marine vessels through the incomplete oxidation of diesel fuel. When in the air, black carbon particles absorb sunlight and generate heat in the atmosphere, affecting cloud formation and rain patterns. When covering snow and ice, the particles absorb the sun’s radiation, generating heat and speeding the melting process. In 2004, 609 tons of black carbon were released into the Arctic region. Shipping other raw materials, such as nickel, also poses major risks, as raw nickel is a known carcinogen.

Coastal waters where a majority of shipping takes place also often contain high levels of biodiversity, and many Arctic shipping routes coincide with spring migration paths used by many marine mammals, including bowhead, beluga, narwhal and the walrus, to reach their summer feeding grounds. When longer shipping seasons coincide with short migration and feeding seasons, such disruption may result in many species’ inability to survive the winter.

In the future, as domestic resource and industrial production increase maritime connection between domestic and international waters, new risks will likely emerge in local waters, where shipments may spread chemical contaminants and invasive species.

Problem Five: Balancing Competition and Cooperation

With a myriad of economic, military, and environmental factors at stake, international political interaction concerning the Arctic is likely on the horizon. However, the nature of these relations has yet to be determined.

Recent geopolitical moves can be analyzed as a precursor for future tensions. In 2014, the United States, European Union, and several other countries imposed sanctions against Russia in response to its annexation of Crimea, which targeted the country’s major banks, defense, and oil and gas industries. Specifically, such sanctions, recognizing the importance of Russia’s Arctic development, prohibited the export of goods, services, or technology in support of oil exploration or production ventures in Russian deepwater, the Arctic offshore, or shale projects.

President Putin has also asserted that the right to transport oil and gas in Russian Arctic territory should be given only to Russian-licensed ships. Through a political lens, however, many view the country’s moves as tied to geopolitical competition, in order to give Russia a further edge in Arctic development.

However, Article 234 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, gives Russia the right to do this by declaring that coastal states may adopt and enforce non-discriminatory laws and regulations for the prevention, reduction and control of marine pollution caused by vessels in ice-covered areas within the limits of a state’s Exclusive Economic Zone. In alignment with this environment consciousness, Putin also declared that Russia should move away from dirtier coal and diesel-fueled transport to cleaner, natural gas fuel. Furthering this goal, Rosneft’s first order from the Zvezda Shipyards, set to be completed by 2019, includes five Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) fueled tankers. Thus, Russia’s close regulation of the ships traveling the Arctic routes can also be seen as a way to advance a more environmentally friendly policy within the region.

Further environmental concerns are driving political cooperation. In August 2015 in Oslo, the five countries bordering the Arctic ocean met to sign an agreement to bar commercial fishing in Arctic territories until scientists improve their understanding of the region, its fish stocks, and their distribution. Since then, negotiations were followed up to also include the EU, China, Japan, and South Korea, and as of November 2017, the nations reached a new deal banning commercial fishing in the central Arctic Ocean for at least 16 years to allow for further study and the development of sustainable policies.

Other promising activities include European investments and engineering to help clean up Russia’s former Soviet era military bases. Since 2003, 13 countries have contributed up to 165 million euros to clear radioactive materials and dismantle nuclear facilities in Northwest Russia. Specifically, Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economics and Labor, with Russia’s Ministry of Atomic Energy have built an impressive new facility to store reactor compartments from dismantled nuclear submarines.

The Rossita in Andreyeva Bay, preparing to disembark on journey to bring Soviet-era spent nuclear fuel to a safe storage location. Originally featured on The Guardian.

More recently in Andreyeva Bay, both Britain and Norway are helping to create a suite of new buildings and install machinery to load a large number of spent nuclear canisters into protective casks and transport the waste to Murmask, where it will be recycled and turned into fuel for civilian nuclear reactors.

While increased access to hydrocarbon resources in the Arctic continental shelf region has the potential to catalyze geopolitical competition, the United Nation’s Conventions on the Law of the Sea (UNCLS) historically has regulated territorial disputes through its requirement that states must submit evidence based claims in order to expand or challenge Arctic territorial boundaries. Between 2007 and 2014, Denmark, Russia and Norway each acted within the UN to submit evidence and claims to extend their continental shelf limits, with Canada likely to follow suit.

Additionally, in September 2010, territorial disputes between Russia and Norway were resolved with successful negotiations delineating a border between Novaya Zemlya archipelago on the Russian side and the Svalbard archipelago on the Norwegian side. Territorial questions between Russia and Denmark are currently being met with similarly open bilateral discussion.

Conclusion

International efforts to help resolve border placements and to protect the Arctic environment show that a precedent clearly exists for cooperation in the area, despite wider geopolitical tensions. While the United States has yet to ratify the UNCLS, it is currently viewed as working fairly for all parties, with littoral states being supportive and compliant. Because economic opportunity is foundational to interests in securing a regional presence, Arctic nations will likely continue their adherence to international law in order to preserve peaceful operations for as long as possible.

Thus, while climate change is resulting in increased economic, military, and environmental activity in the Arctic, political cooperation will likely continue into the future in order to support domestic economies and local environments.