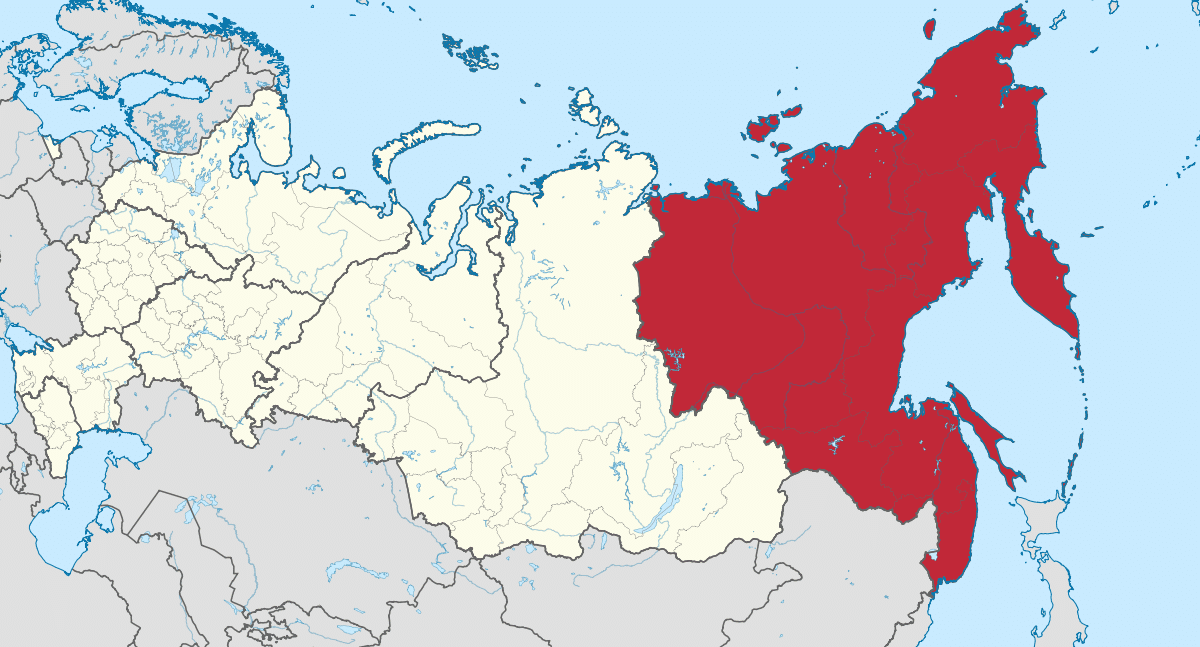

Russian Far East Territory (political borders)

Constituting over one-third of Russia’s territory, home to major natural resource deposits, and essential to maintaining increasingly valuable Asian trade routes, the Far East Federal District is a strategically important asset for Russia. About half of the district’s landmass lies within the enormous Sakha Republic, which is often considered to be geographically more a part of neighboring Eastern Siberia. But even without the republic, the smallest interpretation of the geographic Russian Far East (from the Pacific Watershed to the Pacific Ocean), would still be the world’s eighth largest country if it declared independence, ranked just below the rising power of India.

Russia. The Far East borders Japan and China, with which Russia has nearly always had shaky political relations. Nearby is the volatile Korean Peninsula. Thousands of miles and several time zones away from Moscow, the Far East has always maintained a streak of independence from the central government and has never been easy to rule. Largely mountainous and cold, it supports only a small population: if it were truly independent, it would hold fourth place among the world’s least densely populated states, just below desolate Mongolia. Defending and managing the area, therefore, has always been a challenge for the Kremlin.

In 1639, a band of Cossacks under the leadership of Ivan Moskyitin reached the Okhotsk Sea, completing an important step in Russia’s long drive to push its eastern border to the Pacific and establish ports and a naval presence there. The port and naval base would be appear only after 1858, when the area that would become the Primorsky Krai of today’s Russian Far East was claimed from the Chinese in the Treaty of Aigun. The port, Vladivostok, is also an important industrial and urban center as well as the final stop on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. It is also the district’s largest and wealthiest city, although the administrative capital for the district has been placed in Khabarovsk, slightly further north.

Kamchatka is known for its rugged beauty as well as geothermic and volcanic activity. Pictured here are the “Three Brothers” – granite slabs at the entrance of Avacha Bay. Native legend says that three brothers went to protect their village from a tsunami. They were successful, but turned to stone in the process and now forever guard the bay. Photo: Panoramio.com

The Far East Federal District boasts 6.7 million inhabitants (about 5% of the entire Russian population) most of which reside in the more hospitable and developed southern regions. The area gained a large Russian-speaking population starting in 1861 with the Stolypin agricultural reforms, which offered freedom from serfdom and free land in exchange for relocation to the Russian frontier. In 1882, the Russian government initiated a program bringing 2,500 Ukrainian families to the region annually. Settlement was later supplemented under the Soviets by prisoners of war and Gulag prisoners, who built infrastructure and harvested natural resources.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, the population has been in rapid decline. Loss of the massive Soviet subsidies has meant rapidly deteriorating living conditions for the population, of which 14% has now emigrated to more prosperous areas of Russia. Estimates predict that the population will plummet to an all-time low of 4.5 million by 2015. This alarming statistic has attracted the attention of the Russian government, which is currently discussing repopulation, reindustrialization, and massive infrastructure programs for the area, particularly around its major city, Vladivostok.

Resources and Infrastructure

Economically, the region has traditionally relied heavily on its resources: fish, oil, natural gas, pulp, wood, diamonds, iron ore, coal, gold, silver, lead, and zinc. This natural wealth contributes to the region’s 5% share in Russia’s GDP, and simultaneously to its environmental deterioration. For example, over-poaching of otters for their pelts led to severe depletion of the species in the 19th century, instigating a ban on otter hunting in the 20th century. Today, the poaching of sturgeon is still a major problem, and a porous border with China sees much lumber and wildlife smuggled illegally to the neighboring giant.

Despite the region’s richness, over half the population lives in poverty. Transport infrastructure is virtually nonexistent or in disrepair over much of its territory. The Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Baikal-Amur Mainline, the area’s only major rail services, cover only a sliver of the southern-most territory. Residents of the northern-most land of Chukotka have no continuous overland route to reach Vladivostok, much less Moscow. Oddly, this is the case even as proposals to connect the area with neighboring Alaska via a massive tunnel or bridge are perennially raised.

Infrastructure is gradually improving as regional governments construct airports, roads, piers, geothermal power plants, and housing. Perhaps the biggest boon for the region will be the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) annual summit, which will be hosted in Vladivostok. Planning for the summit has resulted in a massive influx of federal funding for the construction of hotels, bridges, and roads. Federal funds will help create one of Russia’s largest universities, based in Vladivostok, and is also helping to bolster existing universities such as the progressive Vladivostok State University for Economics and Service. Even the US Consulate in Vladivostok is making efforts to increase the number American students studying there – realizing the value that Russia’s Far East will have in the world’s new economic and geopolitical order and wanting to make sure that the US has citizens who understand the oft-overlooked land.

International Importance

The Russian Far East has historically served as the springboard for trade with the Far Eastern nations of China, the Koreas, and Japan. China is Russia’s number two trading partner overall after the European Union, and Japan is its fifth largest source of imports, mostly cars and electronics. The Russian government is prioritizing trade relations with the Far Eastern nations and has been successful in scoring several valuable partnerships. South Korea and Russia, for instance, are collaborating on the construction of an industrial complex in Russia’s Nakhodka Free Economic Area and on the development of gas fields around Irkutsk. There are also plans to connect the Trans-Siberian to Korea’s rail network, facilitating the transport of South Korean exports to Europe. However, this would require a fully reconnected inter-Korean transport system, severed by the Korean War and still effectively unusable due to continued tensions.

Vladivostok will host the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Conference. Several massive projects are being carried out in preparation, including the development of Russky Island with business, sport, and university complexes and a massive bridge. The video above, in Russian, overviews the complexes and discusses the bridge, which is being held up as a centerpiece for developing the Far East.

Despite the potential value of the rail project and the marginal importance of exports to North Korea from Russia’s Far East, Russia has been forced to reconsider its friendly stance toward North Korea, as outlined in the 2000 Treaty on Friendship, Good-Neighborly Relations, and Cooperation. When Vladimir Putin came to office in 2000, he prioritized mending tensions with North Korea, which had tattered by hostility between Kim Jong Il and Boris Yeltsin. However, North Korea’s nuclearization and disobedience of international law have caused Putin to backtrack. In addition, North Korea’s recent attack on South Korea has triggered an exodus of North Korean immigrant workers from the Russian Far East, as they rush home to join what may soon be a war effort. North Korean immigrants are a significant source of cheap labor to the Russian Far East.

Russo-Chinese relations are currently at an all-time high. In 1995, 2004, and 2008, a series of long-standing border disputes were resolved by the two countries. On January 1, 2011 the Eastern Siberia – Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline began oil shipments to China, the pipeline’s biggest beneficiary (it will also serve the Koreas and Japan). In late 2010, in a move to boost their own currencies, Beijing and Moscow bilaterally switched to domestic currencies for use in their growing trade relations, dropping the US dollar. This signals Russia’s commitment to China as a serious trading partner and ally, and one that may overshadow the EU in importance someday.

Although Russo-Japanese trade relations are lucrative, political relations are greatly hindered by a dispute over the Kuril Islands, an archipelago which separates the Sea of Okhotsk from the North Pacific Ocean. These islands are officially under Russian jurisdiction, but Japan claims four of them as its own. The conflict arose after World War II, when Japan was forced to abandon the islands, but the Soviet Union was not explicitly granted sovereignty over them. In large part because of this disagreement, the two countries have actually never signed a treaty to formally end their WWII conflict. A 2008 decision by the Japanese government requiring that school textbooks state that Japan has sovereignty over the islands reignited tensions. Dmitri Medvedev’s 2010 visit to the islands ignited tensions further. The islands are rich sources of fish and also home to mineral deposits of pyrite, sulfur, and various polymetallic ores. Forming a barrier between the open sea and the still more important Russian island of Sakhalin, with its oil, gas, new liquefied natural gas plant and export hub, the islands are also of militarily strategic importance. Russia maintains a military presence on the Kurils.

Domestic Issues and Hope

Officers from a visiting Japanese destroyer are greeted with traditional Russian bread and salt in 2007. Relations have since soured over a long-standing dispute over the Kuril Islands. Vladivostok often hosts visiting warships – including from the US. Photo: Vladivostok News

Domestically, the Russian Far East has recently been brought nearer to Moscow by consolidating Russia’s time zones. These time zones were established by the Soviet Union with an eye to increasing productivity and maximizing daylight. However, in an era of modern governance and global business, they have proven highly inconvenient. Just as workers arrive to work in Moscow, they are clocking out in Vladivostok. This makes getting real-time information and communication between the two destinations very difficult. The zones were also not globally optimized: oddly, Vladivostok was one hour ahead of Tokyo, even though Tokyo is further east than Vladivostok.

President Medvedev, on whose initiative two time zones were cut from Russia, bringing Vladivostok within six hours of Moscow, claims that reducing the time gap between the two ends of Russia will facilitate economic modernization and ease the strain on industry. However, he faces much opposition, as many Russians argue that such changes could affect the physical and mental health of residents of affected regions. Some inhabitants of the Russian Far East are also reluctant to accept Medvedev’s proposal out of principle: they pride themselves in their disassociation with Moscow, and they prefer to keep their distance.

As Russia seeks a greater place on the on the world stage, it will need to develop more of its territory, especially in its east which will allow it to effectively participate in the growing markets of Asia. Russia has promised to focus on trade with East Asia, so greater development of the Russian Far East is logical for the near future. Greater economic ties will also help encourage and facilitate Russia’s work for peace in the East Asian region, in which it has a vested interest due to its territorial proximity and economic interests. Although a logistical challenge due to its size and distance from Moscow, maintaining and supporting the Russian Far East is crucial to Russia’s near- and long-term goals.