Kyrgyzstan, a landlocked, economically poor, and highly mountainous country in Central Asia, keeps an unassuming profile. It lacks the oil and gas wealth of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan. It has lacked the strong, singularly powerful political personalities like Karimov, Berdymukomedov, and Nazarbayev.

But Kyrgyzstan is no mellow backwater. It has had two political revolutions in the past eight years which have made regional and international political waves. Today, it is one of the main routes by which China exports its goods to other Central Asian countries – and is a major recipient of Chinese investment. For Russia, Kyrgyzstan is also important as a trade route and military ally. It is also pivotal in controlling the heroin trade from Afghanistan that is taking a toll on the Russian population. For the US, Kyrgyzstan is seen as a beacon of the democracy it hopes to spread across the planet – and is a military ally and the primary transit point serving US troops in Afghanistan.

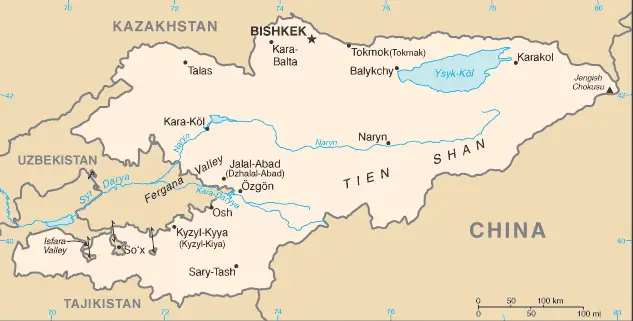

Major locations in Kyrgyzstan (including Bishkek). The large lake in the northeast is Lake Issyk Kul, a massive body of salt water and popular tourist site

The Kyrgyz government has shown itself to be politically ambitious, and able to play major powers off each other to gain the maximum benefit from its relations.

So what do we know about Kyrgyzstan? It is a small country with a big stick.

Quick Stats on a Country of Mountains

Kyrgyzstan is slightly smaller than South Dakota (about 200 square miles) with a population on par with Wisconsin’s (about 5.5 million people). It is almost entirely mountainous, dominated by the Tien Shan range. The mountains are perhaps the most important element to understanding Kyrgyzstan.

Known in Chinese as “The Celestial Mountains” for their height and beauty, the mountains have been coveted by larger empires as a way to place a wall before their competitors. However, they also represent a significant barrier to agriculture and developing large cities and perhaps for this reason have not offered significant military protection to the locals, who have spent most of the past two centuries under foreign domination.

The mountains split the country in half, making transport and communication links between the country’s north and south difficult. This has led to a degree of insularity among the tribes of the north and south, creating the basis for political tensions and competition in modern Kyrgyzstan.

The mountains, while providing many challenges, also play a significant role in Krygyzstan’s development: providing eco-tourism opportunities, hydroelectric production, and some mineral wealth (including significant gold deposits and some uranium). Kyrgyzstan’s is still a predominantly agricultural and rural economy. Cotton and tobacco, grown with the substantial water resources that are, in part, created by the mountains, are Kyrgyzstan’s main exports. Herding, however, is the basis of the subsistence agriculture practiced by much of the population.

Relief map of Kyrgyzstan showing the country’s almost entirely mountainous territory.

The split between north and south Kyrgyzstan was exacerbated by Soviet era policies, which colonized the north (and particularly Bishkek) with large numbers of ethnic Russians and which redrew the southern borders to add significant Uzbek minorities. Ethnic tensions between the Uzbeks and Kyrgyz are today one of Kyrgyzstan’s most pressing domestic problems.

Kyrgyzstan’s two official languages are Kyrgyz and Russian, the former being the state language and the latter being an “official language” of the state – it is a lingua franca and a dominant mode of communication in Bishkek.

Historical Background

Kyrgyzstan has a tradition of epic poetry. Its history reads almost like an epic poem as well. Its four main chapters might be: the early civilizations, Russian occupation, the Soviet era, and post-independence. Throughout the story, dynasties, empires, and tribes have all vied for the region’s cool mountains, fertile valleys, and geo-strategic location along the Great Silk Road.

Kyrgyzstan’s five som note (worth about 20 cents) features the legendary hero Manas on one side and, on the other, Manas Ordo, a 14th century structure thought to house the remains of the hero. Kyrgyzstan recently built a large tourist park around this structure.

The Scythians were the first recorded residents of the region, living in the territory from the 6th century BC to the 5th century AD. Their empire stretched to the Black Sea and they were known for military prowess, horsemanship, and the ability to work fabulously detailed artifacts from gold. Afterwards came various Turkic-speaking groups, who roamed along the Altai, Xinjiang, and eastern Tien Shan mountain ranges. These nomadic groups eventually took up herding and formed the Kyrgyz ancestral tribes. Later arrivals (10-13th C.) include the Turkic Karakhanids and Yenisei Kyrgyz. While there is some historical dispute about their legacies, historians agree the Kyrgyz occupied the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan for several centuries.

The Mongols took over present-day Kyrgyzstan in the 17th century. They co-opted Kyrgyz tribes, either through negotiated agreements or by force (sometimes burning whole settlements to the ground). Afterwards came the Chinese Manchus of the Qing dynasty (18th century) and then the Uzbek Khanate of Kokhand (19th century).

Under the Khan of Kokhand, the Kyrgyz were first exposed to Islam. The spread of Islam in this northern region, however, remained limited. The Kyrgyz, set in their nomadic ways and shamanistic beliefs, continued to worship elements such as the sky, earth, sun, water, and fire, and natural objects like rocks and trees well into the early 19th century. Those who did convert to Islam often chose the Sufi sect – whose propagators allowed the converts to continue some of their shamanistic practices. See Inside Central Asia for more on Central Asia’s cultural history.

The Russians arrived in the second half of the 19th century. At the behest of the Kyrgyz, they defeated the Kokhand Khanate. The Russians then made the region a Russian protectorate. The Kyrgyz revolted against the Russians, however, when the Russians attempted to settle and “civilize” the Kyrgyz (and thus threatened their nomadic and cultural traditions). However, the revolt failed and when the Russian empire dissolved and was replaced with the Soviet Union, the Kyrgyz were quickly enveloped into the new communist system.

Under the Soviets, the Kyrgyzstan’s borders were set under a greater Soviet plan to grid Central Asia and make its natural resources as efficiently extractable as possible. At first, Kyrgyz lands were part of a greater autonomous Soviet republic called Turkestan. Then, in 1924, Turkestan was divided. Later, the Kyrgyz and Kazakh areas were separated. By 1946, the present-day borders were finalized and the territory was called “Kirgizia,” or “The Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, Kirgizia was renamed “Kyrgyzstan,” a more Turkic version of its name. Kyrgyzstan was the first Central Asian republic to declare independence.

Afterwards, Kyrgyzstan struggled in its newfound freedom. All of Central Asia was beset with the basic (and enormous) tasks of developing independent economies (which had once been completely dependent internal Soviet trade) and with developing effective government institutions and a new national identity (both of which had been formerly and formally tied to the USSR and the Communist Party). Developing effective regional relations with each other, particularly in light of the new competition for resources combined with political instability and rising nationalism in each country also proved difficult although a status quo of sorts has now formed.

Kyrgyzstan, in 20 years, has had three presidents, two political revolutions, and one interim president. Kyrgyzstan’s first president was Askar Akayev. He served for three terms before protestors, citing corruption and abuse of power, ousted him in the 2005 Tulip Revolution. He was replaced by Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who, at the time, was a hero of the opposition. However, he too was soon accused of corruption and abuse of power, and was ousted by mass protests in 2010. For a while, Central Asia had its first female leader in interim president Roza Otumbayeva. In the elections of 2011, Otumbayeva decided not to run so as to make sure that Kyrgyzstan would have Central Asia’s first peaceful transfer of power. Almazbek Atambayev became president and he continues to serve today.

Krygyzstan’s political situation remains volatile. With so much political upheaval in recent memory, revolution is never far from the people’s minds. Kyrgyzstan’s fractured geography and regional politics exacerbate this as does its wide range of political parties and ideologies. Many parties and movements are led by relatively rich and powerful interests who sometimes use their resources to fund armies of protestors brought into major cities from poorer rural areas. For many, it is only a matter of time before a new political shift will occur.

Domestic Issues

Kyrgyzstan has a lot of issues on its domestic plate that threaten internal security and stability. The government’s biggest priority is inter-ethnic strife, especially in the south where the dominant ethnic Kyrgyz are often in conflict with large minorities of Uzbeks and smaller minorities of Tajiks and others.

The most infamous ethnic confrontation between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks occurred in Osh and Jalalabad in 2010, when riots resulted in 200 people dead (most of them Uzbeks) and some 200,000 displaced. More recently in 2012, there have been ethnic and border confrontations in the south, as these ethnic tensions have also created stormy relations with Kyrgyzstan’s neighbor, Uzbekistan. The border between the two countries is today closed about as often as it is open. This threat to stability has created an environment in Kyrgyzstan’s south that restricts movement and has thus encouraged overall economic decline.

Islamic radicalism and terrorism are also fed by these conditions. Islamic groups such as the Hizb ut-Tahrir (HUT) garner much attention both locally and internationally. The Kyrgyz government deals with terrorism as aggressively as possible, however, and actual terrorist incidents have been few, especially in the more stable north of the country. However, its possibility is a major issue for many governments – on a local, regional, and global scale.

According to 2011 statistics, 36 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s total population lives below the poverty line, and this number is increasing. Many Kyrgyz (about 15 percent) have given up on finding employment at home and have moved – primarily to Russia or Kazakhstan. These workers are often male breadwinners who leave their families but send most of their paychecks home. Nearly 1/3 of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP comes from remittances from such citizens. However, even this is often not enough to provide for the families and a whole generation of “social orphans” is developing.

Another effect of this instability in southern Kyrgyzstan is that Osh has become a hub for drug-trafficking routes from Afghanistan to Russia and Europe. Kyrgyzstan has also, due to its aging Soviet industrial infrastructure, the poor waste management infrastructure left to it from the USSR, and its current economic and political instability, also has environmental problems – particularly in urban areas.

Foreign Relations

Kyrgyzstan’s most important foreign relationships are with Uzbekistan, China, Russia, and the United States.

Kyrgyzstan’s relationship with Uzbekistan is probably the most emotionally charged. Tensions between the two civilizations is long-standing. The Kyrgyz remember the Uzbek Khanate of Kokhand as being a tyrannical and cruel overlord from which they had to seek the protection of the Russians. The two civilizations were also long diametrically opposed, with the Uzbeks occupying well-watered plains and thus living in large, established cities and Kyrgyz priding themselves in horsemanship and nomadic living.

Another major issue with Uzbekistan is water rights. Kyrgyzstan wants to develop hydroelectric power. Most of its current energy needs are imported and hydroelectric power would greatly improve its energy security – and possibly produce enough electricity that Kyrgyzstan could become a net exporter. However, Uzbekistan depends on flows of water from Kyrgyzstan’s mountains to maintain its large agricultural sector. It worries that Kyrgyzstan could turn water into a “political weapon” if it builds hydroelectic dams to control the flows.

Kyrgyzstan’s most important economic relationship is with China, its eastern neighbor. Kyrgyzstan is the number one Central Asian importer of Chinese goods many of these are then remarketed to other Russia and other Central Asian countries. This import and remarketing is often ranked as the second greatest contributor to the Kyrgyz economy, below remittances from citizens abroad and just above income from the massive Kumtor Gold Mine, which accounts for about 10% of the Kyrgyz economy.

Kyrgyzstan has also received considerable Chinese investment in highways and dairy facilities, cement production, and tourism infrastructure. Most of this investment will produce goods to export to China. China’s cultural influence in Kyrgyzstan is still limited, and is likely to remain so as many Kyrgyz are already wary of possible Chinese domination of their small country. However, continued investment is being actively sought by the Kyrgyz government and thus ties are likely to only become stronger.

Kyrgyzstan’s most important geopolitical relationship is with Russia. Today, the two countries are establishing closer military and economic cooperation. Russia has provided generous financial aid packages, substantial debt relief, and an invitation to join Russian-led economic organizations like the Customs Union. Kyrgyzstan is seriously considering joining the Union, despite the fact that this will likely disrupt its trade in re-sold Chinese goods.

Kyrgyzstan’s relations with the US declined after the most recent revolution. The US had openly supported Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who was ousted in that revolution by his rivals. Russia had actively supported Kyrgyzstan’s opposition and is now benefiting from their rise to power.

Kyrgyzstan’s current relationship with the US is friendly, but not as strong as it was in the 1990s in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet collapse, when the US was a major financial donor. Today, US concerns in the country are dominated by its use of Manas Air Base, the lease for which is set to expire in 2014.

However, Kyrgyzstan’s relationships with Russia and the US are not completely clear-cut either. For instance, Kyrgyzstan negotiated with Russia for an extremely large aid package involving millions of dollars of debt forgiveness, millions in direct aid, and some two billion dollars in loans. Many thought that this backroom deal had attached to it an understanding that Kyrgyzstan would force the Americans out of Manas, which Russia has long considered to be a NATO encroachment into its sphere of interest. However, Bishkek then renegotiated the rental contact with the Americans for higher rent and allowed the base to stay.

Conclusion

Kyrgyzstan is a small country with a long history. It has seen violence, revolution, and endured centuries of outside rule but now consistently ranks as Central Asia’s “freest” country. It has few natural resources yet consistently shows itself as capable of making the most of what it does have. It is a small country with a big stick.