An international student fair at Far Eastern National Univeristy. Mostly Asian students were in attendance. Photo by Lee Chiang.

As an American of Chinese descent, I’ve always had an interest in China. In 2008, I lived in Beijing, China studying Mandarin Chinese and business. That winter I had the opportunity to do some backpacking around the country and visit a variety of places; one stop being the island of Hainan. As it turns out, Hainan is a very popular vacation spot for both the Chinese and Russians. This was probably my first real exposure to “Russian” society and it was very interesting to see the mix of Chinese and Russian signs, with English being much scarcer.

This sparked an interest in how Russia and China, two of the world’s giants, interact and that interest only grew with time. When my program in China ended, I did a little more backpacking; this time through Kazakhstan and into central Russia to learn more about Russia and Russian. It was a once-in-a-lifetime trip, full of hospitality and almost devoid of English, and only piqued my curiosity even further.

In 2009, I found SRAS’s Bordertalk program and decided to travel to Vladivostok, located near the Chinese border in Russia’s Far East, to further my Russian skills and perhaps even improve my Chinese. I also used the opportunity to gain first-hand insight into how the large population of Chinese in Vladivostok live and interact with the native Russians.

This article will detail some of what I found.

A Brief History of the Chinese in Vladivostok

A Brief History of the Chinese in Vladivostok

The city of Vladivostok is closer to Beijing than it is to Moscow – less than 100 miles from the borders of China and North Korea and Japan not much farther away. The Chinese were some of the region’s first inhabitants. Some even still call it “Manchuria,” but officially the region is known as “Primorskiy Krai.” These early Chinese lived in the area seasonally, fishing and farming in the warmer months then returning to the mainland when winter came.

The first Russian expeditions reached this land in the mid 17th century, but communication and cultural barriers as well as competing interests led to a rough start. Border conflicts soon began. The Nerchinski treaty, signed in 1689, would be the first treaty between Russia and China demarcating their mutual borders. However, major conflicts over territory would continue for nearly 200 years and smaller disagreements have persisted even to the present day, with agreements ending conflicts over islands in the Amur River signed only in 2004 and 2008.

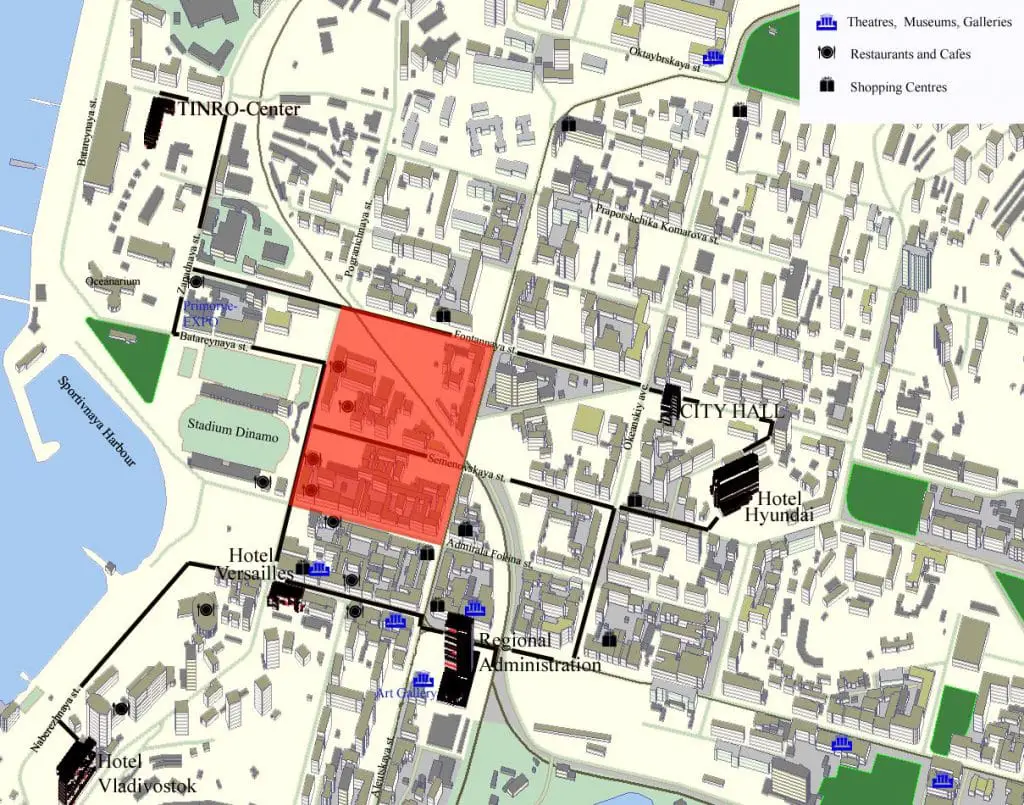

Map of central Vladivostok with Millionka shown in Red – directly across from the Dynamo soccer stadium.

Although disagreements would continue, the region around Vladivostok was stabilized by the Aygunski Treaty of 1858, which officially gave the region to Russia. Russia began constructing a fort and port facilities there almost immediately to serve as a stronghold in the east and solidify its position there. In a few years, family homes would also be built – but even sooner Chinese traders arrived to open shops selling food, clothing, and medicine to the soldiers and sailors. These stores tended to congregate in one area, which became known as “Millionka” (in Russian: Миллионка).

Near the city center, Millionka is now a labyrinth of alleys. At its height at the turn of the last century, possibly 50,000 Chinese were crammed into an area the size of two New York City blocks. The district was famous as source of discount goods, and infamous for its opium dens, brothels, and gambling halls. Gangs had total control over Millionka while police didn’t, or perhaps couldn’t, monitor the area. In 1914, a reported 1,243 crimes occurred in the district alone.

In 1937, Stalin deemed the mass of East Asians living in Vladivostok as “potential threats” to be swept away by his Great Purge. The Chinese, along with many other minorities, were expelled from Soviet soil.

For over half a century, only Soviet citizens lived in Vladivostok, but in 1991 after the fall of the USSR the city reopened and the Chinese rushed back to Vladivostok.

Today, Vladivostok has the second largest minority population in all of Russia, second only to Moscow. Most of these minorities are Chinese. Exact figures are unknown since Russia’s migration service does not publish this information and many foreigners live in Russia illegally anyway. However, the figure can be safely estimated to be in the tens of thousands. There are students, teachers, workers and a handful of businessmen in the city legally and a much larger group, many of whom are involved in retail trade on some level, that operates outside the law.

The Chinese in Vladivostok’s Academia

With China’s recent rise as a global power, Russians have become more interested in their neighbor. Many Chinese teachers and university professors have come to Russia. I spoke with two such teachers, both originally from Harbin, China and who spoke Russian fluently. They taught at the Confucius Institute, a non-profit international organization run by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China with over 280 branches worldwide which seeks to spread Chinese language and culture throughout the world.

The first, Miao Mei Hua, a graduate student at Far Eastern National University (FENU), Vladivostok’s largest university, has lived in Russia for over four years. It is her first trip outside of China but she notes she has many Russian friends, whom she believes are not hard to find. The second, Wen Chun Ze worked as a professor in China and has been teaching in Russia for almost two years. He has traveled much more than Mei Hua, though only within Russia.

They both have very warm feelings towards their host country and claim they have no problems living in Russia. Wen stated that generally “Russians have good impressions and feelings towards Chinese people.” Mei Hua was slightly less definite in her opinions. When asked what she thought about the other Chinese living in Vladivostok, she answered that, “it’s hard to say. The Chinese people here are different… they’re more like guests.” When asked to elaborate on the downsides of life in Russia, both teachers said that other than missing family and friends back home, neither had any complaints about living abroad.

There are also many Chinese students studying in Vladivostok. Gao Ting Yu and Jiao Xing, both 18 years old, came to Vladivostok directly after high school and are currently working on undergraduate degrees at FENU. While their Russian isn’t as good as the teachers I’d previously spoken with, their level is high enough to attend regular university classes alongside native Russians. Both are in their first semesters at university and making their first trips outside of China.

They have only been in Russia for a few months and, other than not really liking the local Russian cuisine, like the teachers, say they like it here. They mentioned some concerns regarding safety, particularly when going out at night, but also seemed to think that the risks were manageable by staying in groups and worth it to be able to learn Russian and receive a university education. They mentioned that with China’s booming population, many of today’s students are finding it very difficult to attend university let alone find jobs after graduation. Another Chinese student, Lixiang, admitted that most students in China who do well in school or university choose to go to America or England to study and that the students coming to Russia often didn’t do as well in school. When asked about what other Chinese do in the city, they responded that most Chinese immigrants work at the market. I asked if they thought these workers had visas, Lixiang immediately replied, “of course.” It seemed as though the idea that there might be illegal immigrants from China in the city had never crossed his mind.

The Chinese in Vladivostok’s Business Sectors

The crowded stalls of Millionka today. Photo by Lee Chiang.

Interestingly enough, Chinese big business has yet to come to Vladivostok. Even the local Russians have noticed the lack of big Chinese business. Boris Sergeiovich, a professor at FENU, states there simply are no big Chinese businesses in Vladivostok and a quick look around the city seems to confirm this.

There are, however, several Chinese-owned shops scattered throughout the city, most often small stores and restaurants. Current market conditions seem to favor small businesses that can operate “under the radar.” While there are Chinese stores and restaurants operating legally, lack of oversight and widespread corruption allows for many businesses to operate illegally; without any kind of documentation.

While the new Millionka, officially now called “Sportivnaya,” as it was renamed in the Soviet era, no longer openly offers the contraband of sex or drugs, it hasn’t completely shed its past and is still known as a place for illegal immigrants, counterfeit goods, and illegal imports. While the police now openly roam its labyrinths of alleys and stalls, they also seem, with rare exception, generally disinterested in enforcing the law there.

While many of the Chinese working at the market were unwilling to divulge their legal status to a stranger, stating they were busy or just simply refusing, a number were willing to speak to me. One, a shoe salesman named Wang, said that he had originally come from Suifenghe, China, a small town near the border between Russia and China. He came just over a year ago, after finishing high school.

Wang operates in a “grey” legal area. He holds a valid 90-day commercial visa, which legally allows him entry into Russia, but does not provide work privileges. Although commercial visas are supposed to operate on a 90-days-in-90-days-out rule, Wang returns to China every three months, applies for a new visa and comes back, thus taking advantage of a legal loophole which makes it technically possible to switch between visas and avoid the rule.

He learned Russian on-the-job after arriving and now speaks a sort of idiomatic conversational Russian. Like the few other market workers I spoke with, he works long hours and receives only a small vacation for New Years, but he says he likes it in Russia. Again, it seemed that for him this was his best opportunity in life and he was making the most of it.

Most of the goods being sold at the market have been smuggled from China. With China’s cheap production costs and none of Russia’s customs or taxes applied, the goods at Sportivnaya are highly competitive on the local market. Boris Sergeiovich from FENU says that as much as 80% of goods for sale in the city are imported – with smuggled goods comprising most of that percentage. Still more of the local goods come from illegal factories operating domestically and producing counterfeit brand name goods – often with illegal Chinese labor.

Smuggling in such goods as lumber, coal, and fish also occurs in the other direction over Russia’s wide and poorly patrolled border with China.

A number of more colorful items are also smuggled to the Chinese. Just a few years ago, an estimated 10,000 frogs, a delicacy in China, were illegally harvested from Russia and smuggled back to China. In August of 2007, three Chinese and four Russians poachers were arrested after attempting to smuggle a shipment of over 100 bears and one tiger, worth about $36,000 in Russia and many times more in China.

How much smuggling occurs is not known, but most agree that those smugglers that are not caught far outnumber those that are.

Sino-Russian Relations in Vladivostok

Some Russians seem to believe that the best solution to stop the criminal activity is to move against the foreigners, rather than questioning why the authorities don’t do more to enforce existing laws and fight the corruption that allows the illegal activities to continue. A nationalist march held in Vladivostok in the summer of 2009 brought out many local skinheads calling for immigrants to be sent home.

However, none of the Chinese I spoke with reported having experienced violence or even racism. Nearly all, the professionals, students, teachers, and market workers, reported having Russian friends. I also, despite my distinctly ethnic features, had no problems with discrimination during my stay. I was stopped briefly by a policeman once for one of Russia’s common random document checks, but was quickly let go after showing my American documents. I noticed that some people would be rather shy or hesitant around me at first, but became friendlier after they found out I was an American. However, I cannot say for certain if this indicates racism against the Chinese or perhaps favoritism towards Americans.

Perhaps it is even more interesting to note that all of the Chinese I interviewed said they enjoyed living in Vladivostok, often citing the nearby ocean as one of the things they liked the most. All agreed that they will return to China at some point. There were mixed opinions on whether or not they’d recommend other Chinese to come to Russia, but the reasons for not recommending usually involved the fact that one would have to leave behind friends and family to live in a foreign culture. Possible discrimination and violence were never mentioned as reasons to stay away.

On the other side of the coin, the Russians I spoke with stated that they did not “hate” the Chinese, but they did have some negative stereotypes about them.

When I asked a group of Russian students what they believe the majority of Chinese living in Vladivostok do for a living, Sasha, a 21-year-old student at FENU and a native of Vladivostok, stated that “they build buildings and sell stuff, repair shoes.” The main advantage of using Chinese workers, he said, is they will do the jobs Russians won’t and more importantly they will do it cheaper. Vika, another student, bluntly stated that, “Russian people are lazy and they don’t want to work cheap.” Sasha notes that, “two years ago there were a lot of Chinese, but now most leave because Russian legislation said that those who do not have documents should leave, [they] can’t have businesses.” While the crack down on illegals has reduced the local Chinese population, there is no law against the Chinese holding businesses in Russia – and there even several businesses which are owned by Chinese nationals. However, it does seem to be a commonly held belief – that none are business owners, and the majority are still working illegally. When directly asked about stereotypes of Chinese people, Vika stated bluntly, “they don’t have a very good education; they [only] speak a few words of Russian.” They all mentioned how the Chinese tend to stick together and that they have “a lot of problems with the police.”

Chinese goods, while being dominant on the market, also have negative stereotypes. “The majority of Russians here in Vladivostok believe that all this stuff that they’re selling is low quality. We believe that in China there are a lot of good quality goods, but in Russia they are bad,” stated Sasha and the group agreed with him. When asked if they shop at Sportivnaya, Sasha said that he does occasionally but “only for kitchen stuff.” Vika and Katya, another student, on the other hand, never do. Vika explained that, “I don’t like Sportivnaya, the fashion there is Chinese fashion. Most of us in Russia believe in quality, we believe in brands.”

The Future of Vladivostok

The Chinese see Vladivostok as a place of opportunity: workers can find work here, and students can find places in universities. The Russians, however, seem to be far less excited. Those who are not planning to go west – to Moscow or perhaps even to Europe, seem open to the possibility of it. There is also a generally held fear in Russia that with the Russians moving out and the Chinese moving in, that Russians may soon be a minority in places like Vladivostok.

Sasha, the Russian student stated that “I believe that today… many people discuss this problem, how many Chinese will be here? People believe that in near future there will be a lot of Chinese stores, businesses.” Referring to Chinese expansion he stated, “we are afraid of it. Russians in general, they don’t want [more Chinese here]. Some people think that the Russian Far East will soon become China. Russians are afraid of that.”

While it is interesting to know that some nationalist-minded Chinese do still consider all of Manchuria, which for them includes Primorskyi Krai and Vladivostok, to be part of China, the sheer fact of migration does not change borders.

Also interesting is that, at least in terms of logistics, it would seem that Russia and China working together would be advantageous for all. Russia has a falling population while China suffers from overpopulation; Russia is in need of long-term infrastructure investment and China is looking to invest in resource-rich countries.

Of course, what may at first seem simply logical is often complicated by politics and history – and the politics and history of Sino-Russian relations have been neither simple nor always logical. However, it’s perhaps the complications masking this obviously massive potential that intrigues me most about relations between Russia and China and the reason I continue studying those relations today.