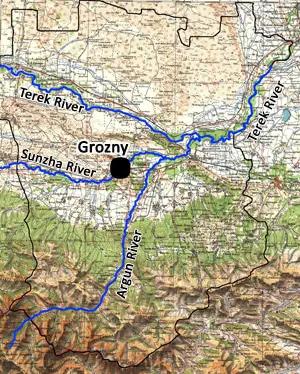

A map of Chechnya and the surrounding region.

Chechnya is a predominantly Muslim region nestled among many turbulent republics in the Caucasian Mountains. Though the deep ethnic, tribal, and religious divisions of the territory make it difficult to develop and rule, Russian and Soviet leaders have long coveted Chechnya for its access to the Caspian Sea and to the Transcaucasus.

Chechnya has traditionally vigorously resisted Russian rule ever since the 18th century, when the Russian Imperial Army began the first of its many campaigns to conquer the Northern Caucasus. Today, it is impossible to understand modern Chechnya without first understanding its violent and complex history.

Chechnya at a Glance

Chechnya has one of the largest absolute majorities of any titular ethnic

Today, Chechnya is one of several semi-autonomous republics within Russia. The status of “republic” means that Chechnya, unlike other constituent components of Russia, can choose its own official language and may have its own constitution to better guarantee certain ethnic, religious, or linguistic rights. While still politically subordinate to the Russian Federation, republics generally have a strong national identity separate from Russia and a populace that desires greater autonomy.

Chechnya is comparable in size to the American state of Connecticut, but with only a third of the population (estimated at 1.3 million according to the 2010 Census). About two thirds of all Chechens live in rural areas and most still practice subsistence farming and herding, as their ancestors did. Many villages are isolated from each other by the rough terrain, which has encouraged a strong sense of tribalism. The terrain has also discouraged major economic development, including the development of large cities, by limiting transport and communication.

A detail of a map showing the ecoregion of the Northern (Greater) and Southern (Lesser) Caucasus. The Northern Caucasus form a nearly impassable wall between Russia and the geopolitical powers to the South.

The capital, Grozny (meaning “fearsome” or “awesome”), is settled on the Sunzha river— Chechnya’s main source of irrigation—between the mountainous south and the lowland north. Although the capital is home to about a quarter million residents, all other cities in Chechnya have fewer than 50,000 people.

The Chechen lowlands enjoy fertile soil, ample rainfall, and a long growing season. Agriculture is now a major component of Chechnya’s growing commercial economy: Chechens produce grapes, grains, and vegetables, and raise cattle, goats, and sheep.

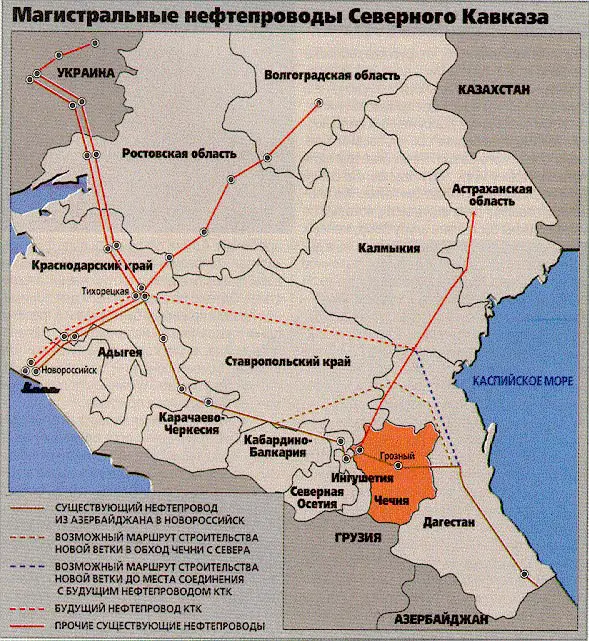

However, the local economy is dominated by oil and gas, and particularly by a small and prosperous oilfield located in the Chechen lowlands. The highlands also offer considerable economic potential in hydroelectric power (particularly along the Terek and Argun Rivers). The area has potential for tourism as well: Chechnya’s beautiful mountains and many geothermic springs may soon begin to draw skiers and other visitors.

Chechnya’s Military Importance to Russia

The main value of Chechnya to Russia, however, is not economic. The rugged highlands provide one of Russia’s few naturally defensible mountainous borders. They separate Russia and the Middle East, with which Russia has many historical rivalries, having fought several bloody wars with Turkey (the Ottomans) and Persia (Iran).

Russia has had two concerns historically when it comes to Chechnya’s geopolitical importance: leaving itself open to invasion from their Middle Eastern enemies, and Chechnya’s influence over neighboring Muslim republics. In the former case, Chechnya serves as Russia’s first line of defense, and losing it would render Russia vulnerable to attack. In the latter case, if Chechnya were to declare independence, its actions may influence the neighboring heavily-Muslim republics—Dagestan to its east and Igushetia to its west—to follow suit.

Dagestan and Ingushetia are strategic to much of the Transcaucasusian transport infrastructure. The Caspian Sea Coastal Road in Dagestan is used to cross the mountain region and access oil-rich Baku, Azerbaijan. The Georgian Military Highway, which crosses between Georgia and Russia at a point called the Roki Tunnel, lies less than two miles from the western border of Ingushetia and leads to the Georgian capital of Tblisi. Thus, the loss of Chechnya, it is feared, could open a strategic door to Russia’s historical rivals and other potential enemies.

Origins and Pre-Soviet History

Archeological evidence, including cave paintings and artifacts, suggests that the Chechens have continuously inhabited the region surrounding the Argun River for over 8,000 years. Until the 15th century, Chechens were semi-nomadic and occupied the highlands, living mostly in caves, until a global cooling phase known as the “little ice age” caused shortened growing seasons and drove them into the more fertile lowlands.

This migration coincided with Chechnya’s rise to strategic importance. Russia, Turkey, and Persia all began to vie for control of the Caucasus as part of their wider geopolitical competition. Chechens converted to Sunni Islam during this time, in part, in hopes that the Ottomans would protect them from Russian invasion and influence.

The Islam of Chechnya, thus, has typically been a particularly political form of Islam. Several efforts have been made to unite the Chechens with other Muslim converts into a Transcaucasian Islamic state.

Although Chechnya was officially incorporated into Russia as a result of the Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813, the movement to found an independent state continued both before and after. This resistance was led by Muslim rebels such as Hadji Murat (immortalized in the eponymous novel by Leo Tolstoy), Imam Shamil, and Sheik Mansur Ushurma, all of whom characterized these wars as religious struggles. Rebellions were common well past the 19th century and often coincided with Russian wars or revolutions, which the Chechen leaders typically saw as windows of opportunity in their struggle.

Chechnya under the Soviets

With the Revolution of 1917, rebel leaders in the Caucasus worked quickly to achieve an independent state. The result was the The Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus and it immediately had to defend itself against first the tsarist White Army and then the Soviet Red Army. The Mountainous Republic was recognized by the Ottomans and the Germans, but despite this diplomatic victory, it fell in 1921, after several years of bloody war, and became the Mountain ASSR within the USSR.

A detail of a map showing the topography of Chechnya and its distinct highland and lowland regions. The city of Grozny and the major rivers have been highlighted. For the full map, which shows all transport routes and Chechnya’s many other rivers, click here.

In the late 1920s, heavily agricultural Chechnya was active in the wide-spread resistance to Soviet collectivization efforts. One rebellion in 1929 resulted in another provisional, semi-autonomous government being established by rebels. As many as 30,000 Chechens may have been killed in purges and other government actions to suppress the rebellion and enforce collectivation. Chechens were also heavily targeted in the purges of 1936-1937.

In the late 1930s, Chechnya was coupled with Ingushetia, its smaller neighbor to the West, to form the Republic of Chechnya-Ingushetia. Ingushetia had voluntarily joined the Russian empire in 1810 and thus was seen as a more secure area that could help temper Chechnya’s restiveness.

Despite these attempts, another major Chechen uprising began in 1940, shortly after the start of WWII. With the assistance of German paratroopers, the resistance lasted through most of the war.. The Germans agreed to help Chechnya in hopes of taking Grozny and its oilfields and moving south to still more oil-rich Baku in Azerbaijan. Grozny itself had, by this time, also been partially industrialized by the Soviets with factories for farm machinery and fertilizer – two industries easily converted to producing military hardware and munitions.

The Germans never succeeded in taking any of these targets and eventually launched a bombing offensive in late 1942 to simply destroy as much infrastructure as possible and remove Chechnya from Soviet hands. By 1943, a Soviet offensive began pushing the Nazis back into Eastern Europe.

In 1944, as the war was drawing to a close, Joseph Stalin forced most of the Chechnya-Ingushetia republic’s population – over 500,000 people— to relocate to Central Asia. A third of the Chechen population died during the transportation and in the first year of resettlement.

The official reason for deportation was that Chechens and Ingush had collaborated with the Nazis and thus the entire population was to be collectively punished. In fact, while collaboration had occurred, it had not been universal; some 40,000 members of the local population had fought for the Soviets. Those soldiers from the Caucasus drafted into the Nazi army were mostly Soviet POWs captured and forced to fight in Western Europe. Hitler did not send them back to the Caucasus to fight as he feared they would likely return to the Soviet forces or, more likely, fight only for the independence of their own homeland.

Map of existing and proposed oil pipelines in the Caucasus and surrounding area. Novorossiysk, the westernmost pipeline point shown inside Russia, exports oil via tankers. Chechnya is shown in red.

Stalin also likely saw deportation as a final solution to break the Chechens’ connection with the land and their ability to fight for it. Additionally, several historians have pointed out that Stalin, in anticipation of a future war with Turkey, sought to move all Turkic peoples, as well as old Turkish allies (which included the Chechens) to somewhere they would not be able to assist Turkey or there they might rebel again in a time of instability.

In 1957, during “de-Stalinization” under Nikita Khrushchev, the Chechens and Ingush were permitted to return to their homelands. Upon arrival, many discovered that ethnic Russians had taken their land, and territorial disputes persisted for decades. Russification policies towards the Chechens also continued, meaning that this “thaw” represented a very small and bittersweet victory and did little to secure their loyalty to Moscow’s rule.

Chechnya after the Fall of the USSR

In 1991, after the failed Communist coup attempt and as constituent republics were declaring independence from the USSR, a militant, unofficial opposition group called the All-National Congress of the Chechen People took power in Chechnya. They stormed the Supreme Soviet, took over major television and radio stations, and declared the communist government of Chechnya-Ingushetia dissolved.

Quickly thereafter, a referendum placed Dzhokar Dudayev, a former Soviet paratrooper and a representative of the Congress, in the post of Chechen president. Declaring Chechnya independent was one of his first acts in office.

Russian president Boris Yeltsin argued that Chechnya had not been an independent entity within the Soviet Union and thus did not have the right under the constitution to secede. He also feared that if Chechnya succeeded, many other parts of Russia might follow suit as regionalism and local leaders grew in strength.

In 1944, Yeltsin launched an air attack on Chechnya “to restore constitutional order.” What was to be a 48-hour mission turned into a two-year invasion in which the Chechens, though severely outnumbered, managed to prevent Russia from gaining control. After both sides endured massive casualties, and after a long ceasefire, a peace treaty was signed in 1997 and Russia agreed to withdraw its troops.

Elections were held soon after, bringing Aslan Maskhadov to power. Maskhadov attempted to maintain as much independence as possible while pressing Moscow for reconstruction money. However, most of Chechnya’s economy had been devastated, many of the federal funds were misappropriated, and much of the population had been internally displaced to refugee camps or overcrowded villages. Crime and corruption spiraled out of control. Extremism and terrorism became more common

In 1999, a series of violent acts outside of Chechnya were blamed on Chechen militants: a bomb explosion in an apartment building in neighboring Dagestan, a bomb explosion in a Russian railway station in neighboring Stavropol Krai, an apartment bombing in Moscow, and several ambushes along the Chechen borders.

Newly appointed Prime Minister Vladimir Putin sent Russian military forces back into Chechnya in what he said was a response to these acts of terror after blaming them, in large part, on Maskhadov and his government. The Russian military was much more resolute in this second invasion, shelling rebel groups, towns, mosques, and even hospitals in an attempt to crush the separatist movement. After Grozny was seized and Maskhadov assassinated, newly appointed Russian president Vladimir Putin was able to reassert direct rule of Chechnya in May 2000.

Chechnya Today

Chechnya’s current leader, Ramzan Kadyrov began consolidating power at the start of the Second Chechen War, when he left the separatist movement to support the Russians, gaining the support Vladimir Putin and Russia’s security services. Of the few rebel forces left after the war, Ramzan Kadyrov has either brought them under his control by passing elements of sharia law, one of their main demands for Chechnya, or by using his own security forces to arrest and, according to many human rights organizations, kidnap, torture, and extrajudicially execute anyone who might oppose him. The media in Chechnya is under tight state control.

Kadyrov supporters, however, point to his regime as an unprecedented era of political stability in a region that has been in turmoil for more than 200 years. Kadyrov has also secured billions of dollars in federal funding from the Russian government. While most social, transport, and economic infrastructure was leveled over the course of the two wars, Grozny is now almost entirely rebuilt with new schools, parks, hospitals, and business parks. The airport in Grozny and the railway connection between the Caucasus and Russia were restored by 2005. Roads in Chechnya have been aggressively rebuilt.

The Russian government has also improved the economy in Chechnya by encouraging Russian companies, both private and state-owned, to invest there. The first sector of the economy to be rebuilt after the war was the petroleum industry, an effort headed by state-owned Rosneft. Today, oil is the largest part of Chechnya’s economy. While Chechnya’s production of 1.5 million annual metrics tons of oil is far less than the 4 million it produced before the war, new exploration efforts are currently underway.

In addition, Lukoil, a privately-held Russian oil company is currently building an industrial park outside of Grozny. Tourism infrastructure, such as a new, multi-billion dollar all-season ski resort called Veduchi, funded by Chechen billionaire and businessman Ruslan Baysarov, was opened in 2012.

With this construction boom and political stability, unemployment rates have improved, falling from 80% to a high, but more manageable rate of 30%.

Rights organizations, however, point to the political price paid for stability and encourage governments and international organizations to press Russia for greater democracy in Chechnya. Kadryrov has openly called democracy a “western lie” and has publically argued that democracy cannot work in such an unstable place as Chechnya.

Although it is relatively stable today, Chechnya still suffers from some rebel activity and volatility. The government displaced by the Second Chechen War continues to unofficially operate, although it has changed its name to the “Caucasus Emirate.” This government is now headed by Doka Umarov, an Islamist militant who has been blamed for several terrorist attacks in Russia and who has publically called for his followers to use “maximum force” against Russia’s 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi.

Internationally, two ethnic Chechen immigrants prompted a city-wide manhunt after allegedly setting off bombs at the Boston marathon in March 2013. While the two had not grown up in Chechnya, it later surfaced that they may have been radicalized, in part, while visiting neighboring Dagestan.

Despite the difficulties in retaining the region, Russia continues to see the Northern Caucasus as integral to Russian security. Russia also sees Chechnya as a key to retaining the Northern Caucasus, despite the massive cost and difficulty in doing so. It is also feared that an independent Caucasus would be even more unstable and militant than one under Russian control.

While Chechnya can be considered today relatively stable, the bloodshed in the region has not altogether stopped and its geopolitics will continue to be a fascinating, if tragic, subject to study for many years to come.